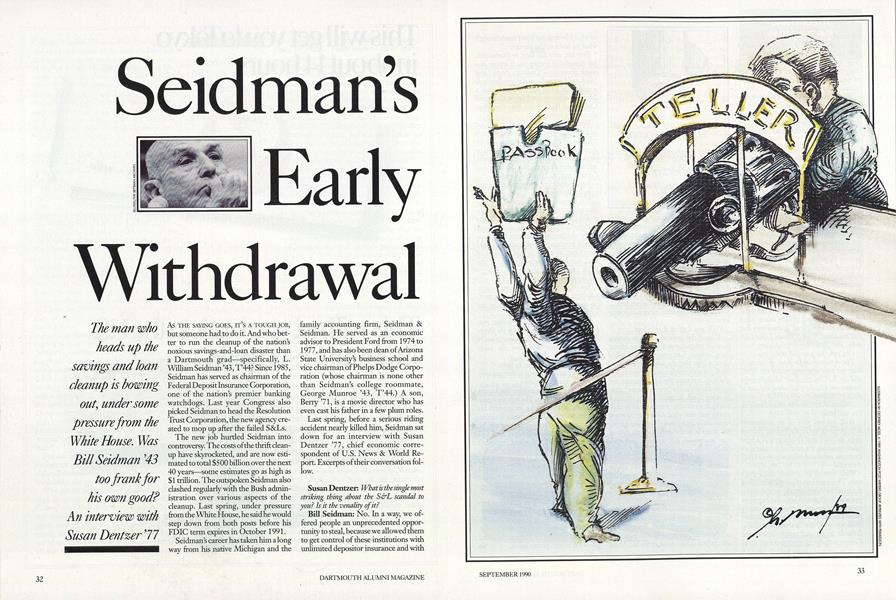

The man who heads up the savings and loan cleanup is bowing out,, under some pressure from the White House. Was Bill Seidman '43 too frank for his own good? An interview with Susan Dentzer '77

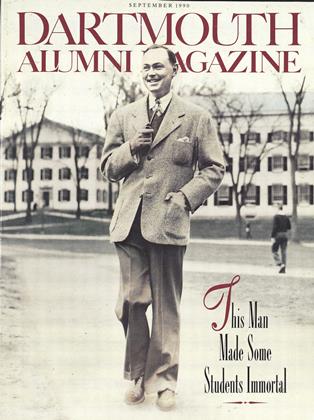

As the saying goes, it's a tough job, but someone had to do it. And who better to ran the cleanup of the nation's noxious savings-and-loan disaster than a Dartmouth grad specifically, L. William Seidman '43, T'44? Since 1985, Seidman has served as chairman of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, one of the nation's premier banking watchdogs. Last year Congress also picked Seidman to head the Resolution Trust Corporation, the new agency created to mop up after the failed S&Ls.

The new job hurtled Seidman into controversy. The costs of the thrift cleanup have skyrocketed, and are now estimated to total $500 billion over the next 40 years—some estimates go as high as $1 trillion. The outspoken Seidman also clashed regularly with the Bush administration over various aspects of the cleanup. Last spring, under pressure from the White House, he said he would step down from both posts before his FDIC term expires in October 1991.

Seidman's career has taken him a long way from his native Michigan and the family accounting firm, Seidman & Seidman. He served as an economic advisor to President Ford from 1974 to 1977, and has also been dean of Arizona State University's business school and vice chairman of Phelps Dodge Corporation (whose chairman is none other than Seidman's college roommate, George Munroe '43, T'44.) A son, Berry '71, is a movie director who has even cast his father in a few plum roles.

Last spring, before a serious riding accident nearly killed him, Seidman sat down for an interview with Susan Dentzer '77, chief economic correspondent of U.S. News & World Report. Excerpts of their conversation follow.

Susan Dentzer: What is the single most striking thing about the S&L scandal to you? Is it the venality of it? Bill Seidman: No. In a way, we offered people an unprecedented opportunity to steal, because we allowed them to get control of these institutions with unlimited depositor insurance and with

no restrictions on what they did with the money. And that attracted some of the finest felons that the country knows how to produce. It's a combination of the government's failure and the ability of those without any need to be honest to take advantage of it.

You've had a very long and distinguished career in both the public and private sectors. There are those who suggest that heading up the FDIC and now the Resolution Trust Corporation is like ending your career with Custer's last stand.

Well, the Indians haven't gotten us yet.

But you are surrounded.

I hope I'm not being unduly immodest, but the fact of the matter is that the FDIC has survived the worst period in its history. It is solvent. The condition of banks is improving. Now, in terms of the S&L debacle, as I said many times while this reorganization was being considered, we don't want it, we'd prefer somebody else do it, anybody who does it is going to be the most unpopular person in public life. In terms of the kinds of duties involved, handling this cleanup is the equivalent of being an undertaker, a garbage collector, and an IRS agent all rolled into one.

I want to ask you a little bit about life in Washington. You've always been known as something of a plain speaker, and in fact I found an old Wall Street Journal story that was headlined, "Bill Seidman Looks Cherubic, But That May Be Misleading."

Oh, yes, that's an old story, yes.

The conventional wisdom, of course, is that you were drummed out of the FDIC and the RTC by the Bush administration because you told the truth about the costs of the S&L cleanup.

They couldn't have drummed me out; I'm still here.

Well, but you were in an anticipatory way drummed out on the grounds that you spoke the truth and Washington is a town where speaking the truth is considered an enormous social and political gaffe. What's the truth?

Well, first of all, I don't think that's true. There are lots of people who speak the truth in Washington—not as many, perhaps, as we would hope for, but there are some. In any event, there were clearly people in the administration who were unhappy with the fact that I found it difficult to go and testify before the Congress and tell them anything except what I knew. That's unfortunate, but it's fairly common. The administration had its mission, and I headed an independent agency, which gave me, in my view, other responsibilities. So we weren't always in agreement. But, as a matter of fact, I went to President Bush to tell him that I thought five years was enough and that we ought to arrange for a transition. Unfortunately, some of his people, I guess, were impatient in that regard.

Wanted the transition sooner rather than later...

Well, yes. I think that's clear.

A lot of this impetus has been coming from the political arm of the White House, John Sununu. Last year, when you talked about a plan that the administration had developed to impose fees on depositors as part of a way to finance the S&L cleanup, you referred to this as the "reverse toaster"plan. In other words, it would be like the bank taking away a toaster from you rather than giving you one. And Governor Sununu responded by saying something about having you insert a toaster into a certain part of your anatomy. Is this the source of the difficulty?

Do you anticipate patching things up with Governor Summit, or does it matter? Not to me, no. I mean, I don't have any personal relationship with him. I've only talked to him twice in my life. Most of what I hear about him I read through what he leaks to the papers.

Your son, who also went to Dartmouth, has succeeded in getting you to appear in a couple of movies "Ordinary People " and "Rich andFamotis" and wanted you to do a western in which you would appear as a Mexican soldier opposite Mar got Kidder and Christopher Walken, but you turned him dawn. How come?

Well, I went over the script, and we had a little argument. I wanted to have the best Mexican soldier's part, and he didn't want to give me that. I wanted to be the last one to die in the big battle, but he didn't allow me that. So I decided I'd hold out, so I just got dumped.

Just a persnickety actor type who wanted to influence the script.

No, it wasn't any major deal. The one that really makes me sad is that he had a wonderful part for me in "Dead Poets Society." I was going to be one of those stuffy old faculty members that were always hovering around, and I would have been so good in that. Instead of that, something came up here at the FDIC, and I made the very...

Like a bank failure?

Yes I made the very bad decision to stay here and not go and take that part. So that was the biggest mistake in my long acting career.

You have some interesting hobbies that one presumes you might turn to the future in your retirement or whatever it is you re going to call your departure. You make mobiles.

Yes. I have some right in here. And my understanding is that you were pals with Alexander Calder.

Well, I certainly knew him. Yes, I spent some time with him. He was very cautious about whoever he let get into his studios to see how he made mobiles, because he was the mobile king and he didn't want to be challenged. And so I told him I made mobiles, and that didn't endear me much. But then he took a look at them and he decided it'd be okay for me to come to his studio because I would never be competition to him.

Is that something you 're going to do more of in the future?

Oh, who knows? I've threatened to grow raspberries and mountain herbs. We have a ranch, you know, in New Mexico. I haven't really thought seriously about what I'm going to do. But I guess I'd better, pretty quick.

"We offered people an unprecedented opportunity to steal."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

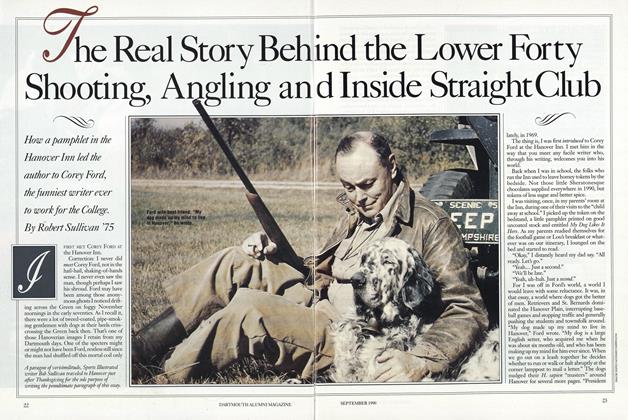

FeatureThe Real Story Behind the Lower Forty Shooting, Angling and Inside Straight Club

September 1990 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeaturePROBLEM SOLVER

September 1990 By John Aronsohn '90 -

Feature

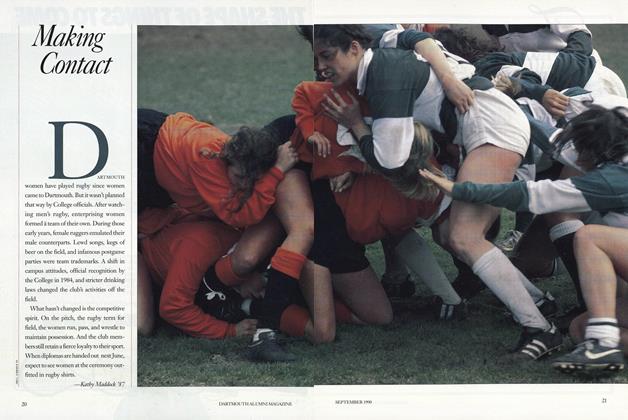

FeatureMaking Contact

September 1990 By Kathy Maddock '87 -

Article

ArticleMOTHERS AND DAUGHTERS

September 1990 By Professor Marianne Hirsch -

Article

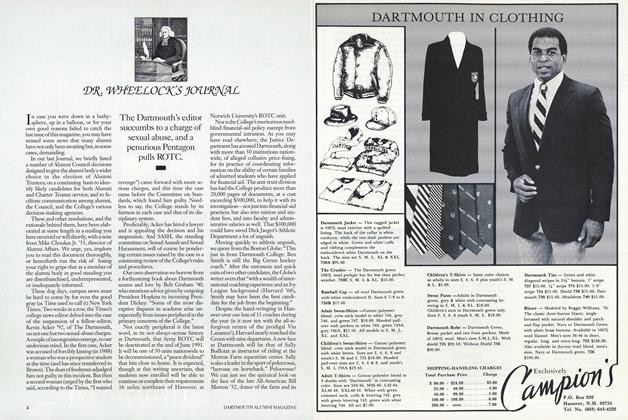

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

September 1990 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1960

September 1990 By Morton Kondracke

Susan Dentzer '77

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO AVOID INDIGESTION (AND STAY HAPPILY MARRIED AT THE SAME TIME)

Sept/Oct 2001 By HORACE FLETCHER -

Cover Story

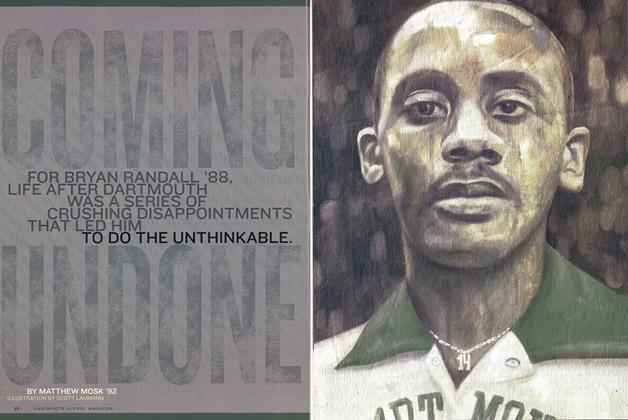

Cover StoryComing Undone

Jan/Feb 2005 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

FEATURE

FEATUREThe Fixer

JULY | AUGUST 2016 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1972

JULY 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Cover Story

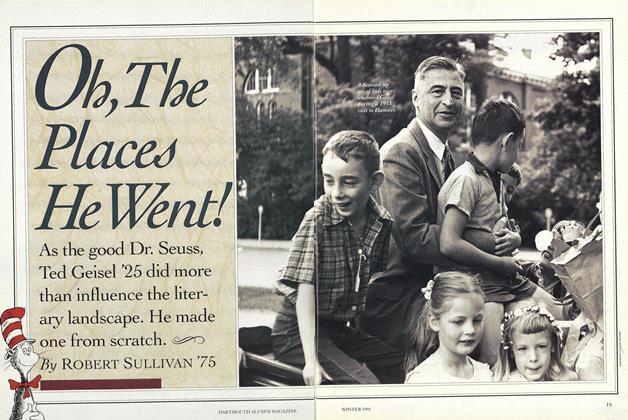

Cover StoryOh, The Places He Went!

December 1991 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

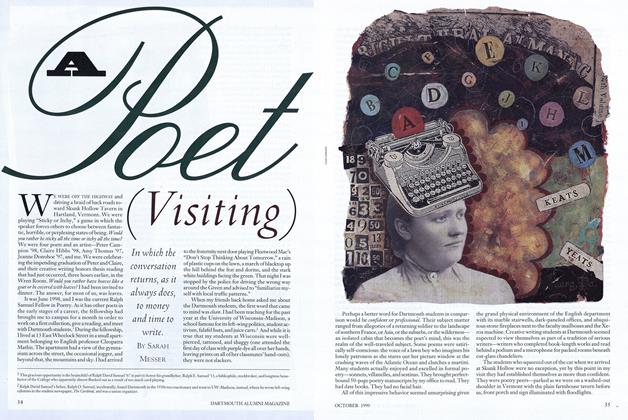

FeatureA Poet (Visiting)

OCTOBER 1999 By Sarah Messer