A complicated relationship emerges from the literary shadows.

In the late 1970s, when I first taught a course on mothers and daughters in comparative literature at Dartmouth, I thought of the motherdaughter relationship, in Adrienne Rich's terms, as "the great unwritten story." Rich elaborates: "The loss of the daughter to the mother, the mother to the daughter is the essential female tragedy. We acknowledge Lear (father-daughter split), Hamlet (son and mother), and Oedipus (son and mother) as great embodiments of human tragedy; but there is no presently enduring recognition of motherdaughter passion and rapture." My course explores the stories of mothers and daughters in myth, fairy tale, and literature, as well as in psychological and feminist theory. The course itself is an exercise in feminist revisionfinding speech and meaning where we believed there was silence and absence. Often that means reading novels and stories for characters and plots that appeared marginal or secondary.

We begin with texts that marginalize women—mothers in particular as in Sophocles's treatment of Oedipus's mother, Jocasta. She stands by, silent and powerless, the background to Oedipus's search for his origins. It is impossible for us even to imagine her story: her decision to kill her child, her guilt, her own response to the revelation that she married her son.

In myths and fairy tales where mothers do have a voice and a plot, their roles often assume extreme and terrifying proportions, reinforcing cultural perceptions that antagonism between parents and children of the same gender is inevitable. As we reread a story like the Grimm Brothers' "Little Snow White," however, we see the queen not as the evil stepmother but as the creative female artist who, rebelling against the sacrifices that motherhood entails, schemes to preserve in herself what the culture values youth and beauty. In the matricidal story of Electra and Clytemnestra, we confront a mother-daughter hostility fostered by the daughter's attachment to her father and brother and the public power they represent. The mother-daughter relationship is dominated by a structure of male power which pushes them into an antagonism from which neither can emerge either whole or heroic.

There are, however, women-centered myths that highlight enduring mother-daughter attachments. In the Homeric hymn "To Demeter," which dates from the seventh century B.C., the earth goddess Demeter has the power to destroy humans when Hades abducts her daughter to the underworld. Demeter is pacified only by Persephone's return for a part of each year. Although the hymn presents loss and separation as inevitable, it validates Demeter's bereavement and her desire for her daughter's continued love. The oscillation between motherdaughter reunion and separation is a pattern taken up by many women writers to illustrate the ambivalences of this complicated relationship.

In the nineteenth century, women writers viewed maternity as life-endangering, subversive, a condition to be avoided at all costs. Charlotte Bronte's Jane Eyre, an orphan heroine who succeeds by virtue of her motherlessness, illustrates this fear. She evades the trap of maternal identification which, in this period, was often equivalent to the repetition of a failed unhappy life, if not to death. Even after Jane marries Rochester and becomes a mother, she refuses to claim what she calls "his first-born."

By the beginning of the twentieth century, mothers occupied central locations in women's novels,, but their stories were told from the perspective of daughter-writers. In Virginia Woolf's To the Lighthouse, the young artist Lily Briscoe sees the maternal Mrs. Ramsay as mysterious, nurturing, and artistic in her own right. Yet, in order to paint, Lily ultimately distances herself from this powerful maternal influence. In a characteristic pattern of oscillation, she defines a femininity that is connected to maternal love but ultimately rejects and surpasses marriage and motherhood.

Even the feminist literature of the 1970s reflected what Adrienne Rich terms "matrophobia" the fear of becoming one's mother. Identifying as "sisters," feminists often excluded and feared the influence of the mothers they perceived as sellouts to patriarchy. Toni Morrison's Sulci illustrates the pitfalls of such estrangements.

Matrophobia may partially explain why maternal accounts of motherdaughter attachment and separation can be so difficult for mothers to write and for daughters to read. Yet many recent stories and novels written from the mother's perspective attempt to break with portraits from the past. In the works of such authors as Grace Paley, Toni Morrison, and Sue Miller, mothers present themselves as neither all-powerful nor powerless, as neither simply objects of their child's development nor as subjects in their own right. Far from being apologists for the status quo, these mothers are often more radical than their daughters, although their rebellion is always qualified by the work of raising their children as acceptable members of their society. Inasmuch as a mother is simultaneously a daughter and a mother, in the house and in the world, dependent and depended upon, maternal discourse is necessarily plural. Maternal narrators speak of anger and love, of pleasure and pain, of conflict between nurturing and self-nurturing. They speak of small, material, and often trivial decisions and choices, of their lack of preparation for those choices, of unending guilt and inadequacy. But they are also competent, strong, joyful; they take pride in their children, they grieve for them, they remain connected and accept distance. In Tillie Olsen's "I Stand Here Ironing," a mother thinks lovingly about her daughter's life as she is doing the ironing. In Alice Walker's "Everyday Use," a mother has to decide which of her two daughters needs her gift of two heirloom quilts more than the other. This is not material for enduring human tragedy as we have been taught to know it, but it is the content of women's lives.

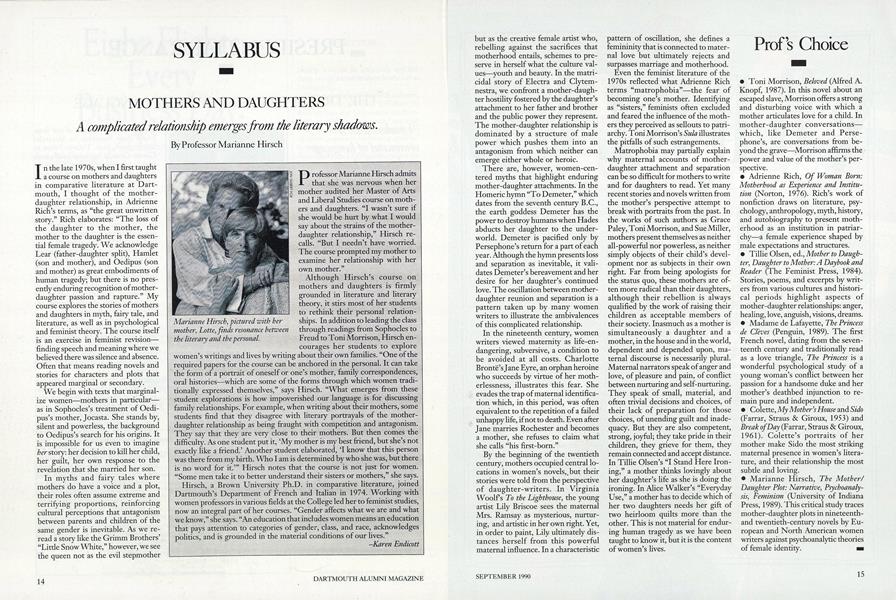

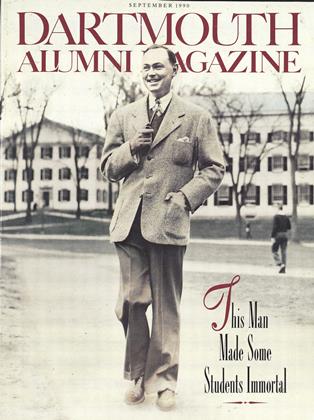

Professor Marianne Hirsch admits that she was nervous when her mother audited her Master of Arts and Liberal Studies course on mothers and daughters. "I wasn't sure if she would be hurt by what I would say about the strains of the motherdaughter relationship," Hirsch recalls. "But I needn't have worried. The course prompted my mother to examine her relationship with her own mother."

Although Hirsch's course on mothers and daughters is firmly grounded in literature and literary theory, it stirs most of her students to rethink their personal relationships. In addition to leading the class through readings from Sophocles to Freud to Toni Morrison, Hirsch encourages her students to explore women's writings and lives by writing about their own families. "One of the required papers for the course can be anchored in the personal. It can take the form of a portrait of oneself or one's mother, family correspondences, oral histories which are some of the forms through which women traditionally expressed themselves," says Hirsch. "What emerges from these student explorations is how impoverished our language is for discussing family relationships. For example, when writing about their mothers, some students find that they disagree with literary portrayals of the motherdaughter relationship as being fraught with competition and antagonism. They say that they are very close to their mothers. But then comes the difficulty. As one student put it, 'My mother is my best friend, but she's not exactly like a friend.' Another student elaborated, 'I know that this person was there from my birth. Who I am is determined by who she was, but there is no word for it.'" Hirsch notes that the course is not just for women. "Some men take it to better understand their sisters or mothers," she says.

Hirsch, a Brown University Ph.D. in comparative literature, joined Dartmouth's Department of French and Italian in 1974. Working with women professors in various fields at the College led her to feminist studies, now an integral part of her courses. "Gender affects what we are and what we know," she says. "An education that includes women means an education that pays attention to categories of gender, class, and race, acknowledges politics, and is grounded in the material conditions of our lives."

Karen Endicott

Marianne Hirsch, pictured with her mother, Lotte, finds resonance between the literary and the personal,

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Real Story Behind the Lower Forty Shooting, Angling and Inside Straight Club

September 1990 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

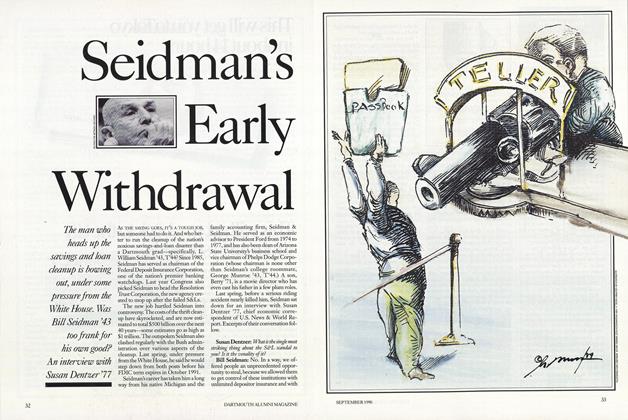

FeatureSeidman's Early Withdrawal

September 1990 By Susan Dentzer '77 -

Feature

FeaturePROBLEM SOLVER

September 1990 By John Aronsohn '90 -

Feature

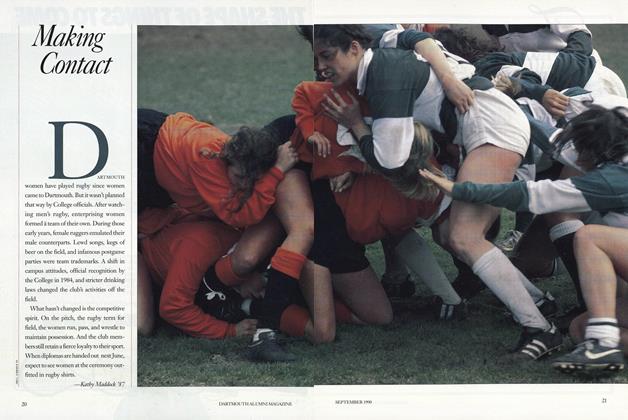

FeatureMaking Contact

September 1990 By Kathy Maddock '87 -

Article

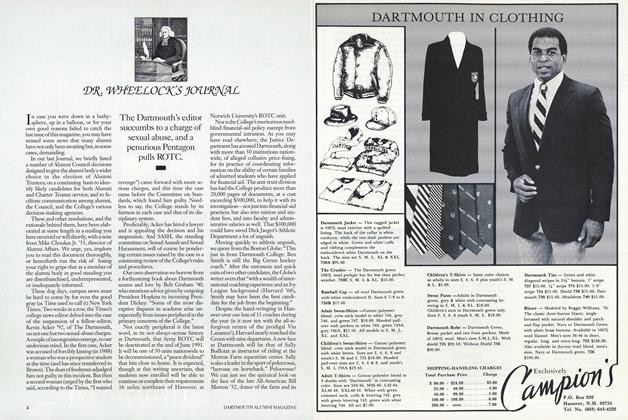

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

September 1990 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1960

September 1990 By Morton Kondracke