AFTER THE 400,000 DEATHS, THE HORROR stories, the ten years of protests and politics, we as a society have reached a point, according to the writer Andrew Holleran, when the only article we want to read about AIDS must begin: "CURE FOUND!"

Enter Victor F. Zonana '75.

Two years ago, Zonana approached his editor at The Los Angeles Times with a proposition. He no longer wanted to write about business, he said. He wanted to write about AIDS. Only about AIDS.

Until that time, Zonana or Z-Man, as his Dartmouth friends call him—was one of The Times's senior business reporters. Hired away from The Wall Street Journal, where he'd been writing front-page columns since the summer before his senior year, Zonana was tapped to help boost the paper's expanded business coverage. One evening, taking a break from a business-related story, Zonana decided to attend the unveiling of the giant quilt memorializing the AIDS dead. Just as the ceremony was about to begin, the auditorium went dark. Suspecting that the blackout could be an act of anti-gay sabotage, Zonana turned instandy from spectator to reporter.

The blackout was truly accidental, but that experience started Zonana to thinking. "I had just read The Plague, and I wrote that the quilt was for some a splash of color in an epidemic that is bleak and gray and relentless, like the plague described by Camus. I was moved by the magnitude of the loss and the magnitude of the love of the survivors."

At first, Zonana's proposal to his editor met with the skepticism that Holleran prophesied: AIDS is a sad story and people know all about it. But Zonana persisted. "I had learned from my reading of the book that, yes, plagues are dull and repetitive and depressing. But the chronicling of them needn't be." Shelby Coffey HI, The Times's newly chosen editor, was swayed.

Night has fallen here, and the monkeydoctors are having a party.

From the first sentence, Zonana's reporting proved his claim. The article about a symposium on nonhuman primate models for AIDS infection grabbed readers' attention with a strange, irreverent lead and propelled them into a world of life-and-death biomedical research. A chilling later piece provided the first look at a Cuban quarantine center for people carrying the AIDS virus. Another feature viewed grassroots activism through the eyes of a 28-year-old Wall Street bond trader who left the bond market to become a fundraiser for ACT UP, the AIDS activist group. Zonana profiled Mathilde Krim, a wealthy New York doctor and philanthropist who founded the American Foundation for AIDS Research. A later story took readers through the flip side of AIDS—a poignant profile of a poor, young Latina afflicted with the usually fatal disease.

Other papers cover AIDS fall-time, but by common consent Zonana's reporting stands out. "The problem with AIDS is that it's an extremely complicated issue involving government agencies, tough political issues, and complex science. Most reporters simply haven't taken the time and energy to do their homework," said Larry Kramer, author of seminal works on AIDS and a leading activist. "Why Victor is head and shoulders above the rest is that he's done his homework and he understands."

Shelby Coffey, the Times editor, calls what Zonana does "depth reporting."

What sets him apart, says Coffey, is his ability "to understand the complexities and convey them with very fine narrative writing." In 1990, The Times nominated Zonana and his AIDS journalism for a Pulitzer Prize.

The articles seem to have made an impact beyond the world of journalism as well. The day after reading the Krim profile, Joan Kroc, the McDonald's heiress, donated $1 million to AIDS research. An investigative article on AIDS Project Los Angeles exposed mismanagement and neglect, and resulted in the resignation of the project's chairman. After Zonana and other journalists wrote about the high cost of the AIDS treatment drug AZT and nationwide protest by AID S activists Burroughs Wellcome, the drug's manufacturer, lowered the price 20 percent.

Zonana refuses to take the honors for these outcomes. He prefers to credit The Times, Coffey, and former Times publisher Tom Johnson for standing behind his decision to tackle AIDS fulltime. As the protagonist Rieux declares in The Plague: "There's no question of heroism in all this. It's a matter of common decency."

"There are easier ways to meet Liz Taylor than by pretending you have the moststigmatized disease of this century," Callensaid dryly, rolling up a shirt sleeve to displaya Karposi's sarcoma lesion for emphasis.

Sitting uncomfortably on the wrong side of a tape recorder for the first time in his life, the journalist acknowledges the wiry, intense Zonana searches for precise words to explain his work. "AIDS kills somebody in the U.S. every 12 minutes. In San Francisco, in a day, AIDS kills four or five. And yet the world went crazy when an earthquake killed 11 people in the city. AIDS is also a natural disaster. I don't know if my words are adequate. So many more eloquent people have spoken. I guess I want the world to care. I want it to be roused to anger and action. That's not very eloquent. I'm much better at citing other people's words."

"Nearly one person in 20, "Jacobs said,shaking his head in horror. "I was in WorldWar II. You could do better than that in acity under attack."

Zonana lives in the middle of San Francisco, the "city under attack." On the answering machine when he returns home this evening is a progress report on an acquaintance in the hospital, dying of AIDS. He reflects a moment on the message. "I think everybody has it within him or herself not to shun a person with AIDS. It's as simple as that. Why should people care? Because people are dying."

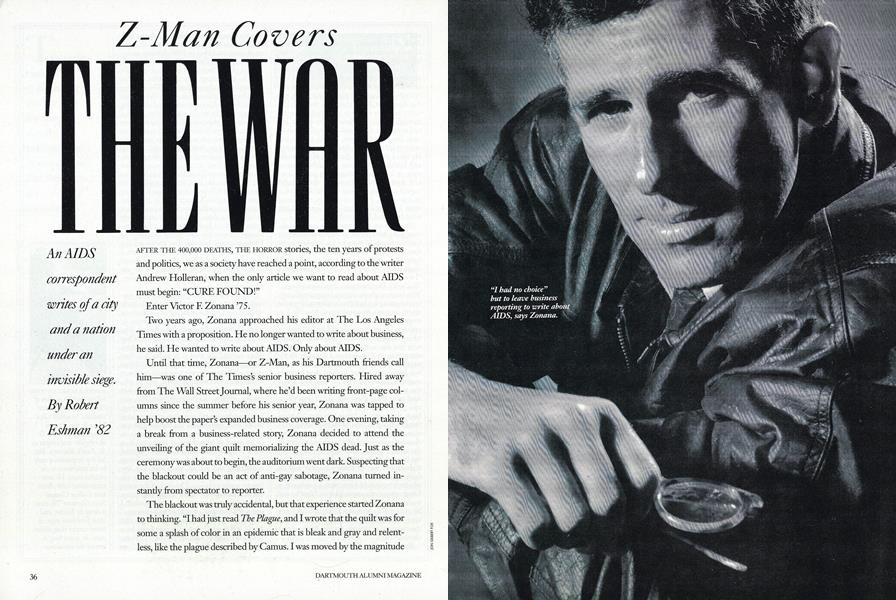

Finding himself in the midst of an epidemic, watching it cut a swath through his community, Zonana feels he "had no choice" but to leave business writing for AIDS reporting. "I see this as the antidote to depression. This is action," he says. He had read a speech by Larry Kramer. "Don't you feel you have a duty to give something back, if only for the mere fact that you are alive today?" Kramer demanded. Says Zonana: "That really spoke to me."

Six and a half years after he was foundto have AIDS, Michael Callen author,activist, singer, and songwriter—half-jokingly credits his longevity to "luck, ClassicCoke, and the love of a good man."

In speaking to others through journalism, Zonana's chronicling focuses on the heroes, not the villainy, of the AIDS story. Heroes like activist Michael Callen, who has spearheaded a movement for empowering people with AIDS; Martin Delaney, who put his consulting business on hold to fight for wider access to experimental drugs; an AIDS-infected Latina who spends her last days lecturing on safe sex to high school students; doctors struggling toward a cure as if their own lives depended on it.

For Zonana, these people confirm Camus's optimistic assertion that, "in times of pestilence, there are more things to admire in men than to despise."

Zonana hopes that, confronted with such examples, people will be moved to action or, at the very least, to shed fears and prejudices that have so made AIDS more of a controversy than an affliction. "I hope the garden-variety misconceptions are already dead and buried," he says. "Simple logic would tell you that if it were easy to get AIDS from casual contact everybody in San Francisco would be dead.

"But the most common misperception still is that people with AIDS are at fault, as if they knew. Because it is a preventable disease, people don't see the 11-year time lag. They see people continuing to fall sick with AIDS, and it doesn't even occur to them that these people are falling sick from something they did in 1979, when nobody had heard about the disease. Unless you really think about it, it's easy to fall into that trap."

More insidious traps remain harder to escape through simple logic. "Over 35 percent of the people questioned in a recent L.A. Times poll said AIDS is God's punishment of homosexuals." Zonana shakes his head, then smiles. "The answer of course is that if AIDS is God's punishment of homosexual men, then lesbians are God's Chosen People. Lesbians have the lowest incidence of AIDS."

Three years ago, after he had watchedhis five best friends die of AIDS, interior designer David Ramey fled his nativeSan Francisco to begin a new life acrossthe bay...

A fleeing populace, battles being waged, the blood of innocents Zonana's writing does not portray merely a society at risk, but a society at war. "My subject is War, and the pity of War," wrote the poet Wilfred Owen in 1918, and this cry echoes throughout Zonana's work.

"The virus is really poised to march over whole new populations. The virus is not impressed that you are heterosexual or white. It just likes to eat Tcells," Zonana says, referring to the white blood cells that are attacked by the AIDS virus. While he believes new technologies are making AIDS less of an instant death sentence, he sees the disease continuing to stretch society's resources, especially the resources of compassion.

But in the long run, Krim said, "Ithink AIDS can have a civilizing effecton us, if we don't let it destroy our systemof values and human relationships..."Perhaps, she added, AIDS may even"make us more tolerant."

The words Zonana is so expert at citing are ultimately not about viruses, monkeys, drugs, and death, but about acceptance. "I may never reach the hardcore bigot and hater but there are lots of people in the middle ground. I'm trying to get people to understand that gays and people with AIDS are not to be feared."

But why keep crying out about AIDS to a populace tired of the very word? The journalist reflects a moment longer. "Even if I write the story that says, 'Cure Found!' I'm afraid I'll never be able to write the one that says, 'Hate and Intolerance Eliminated.'" And that, Zonana concludes, is the real story.

"I had no choice"but to leave businessreporting to write aboutAIDS, says Zonana.

Zonana's profile of Mathilde Krim,founder of an AIDS research group,inspired a million-dollar donation.

In one story, a bond trader quits to raisefunds for the activist group ACT UP.

An AIDScorrespondentwrites of a cityand a nationunder aninvisible siege.

"Even if I write the story that says, 'Cure Found!'Fm afraid Fll never be able to write the one that says,'Hate and Intolerance Eliminated.

Los Angeles writer Rob Eshman's laststory for this magazine, "Shrink Rap,"appeared in the November issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

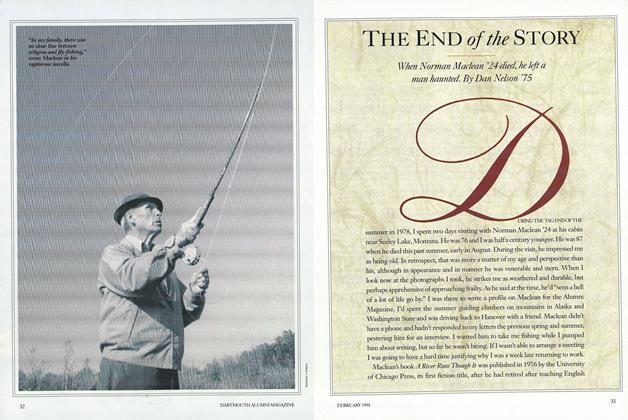

FeatureThe End of The Story

February 1991 By Dan Nelson '75 -

Feature

FeatureOUR PASSIONATE PREFERENCE

February 1991 By Joseph D. Mathewson '55 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryNow For The Hard Part

February 1991 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureWHO OWNS DARTMOUTH?

February 1991 By Joe Boldt '32 -

Feature

FeatureIs Harvard Becoming More Like Dartmouth?

February 1991 -

Feature

FeatureWe asked some students: WHAT ONE THING WOULD YOU CHANGE ABOUT DARTMOUTH?

February 1991

Robert Eshman '82

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryESCAPE ARTIST

May/June 2013 -

Feature

FeatureMy 65 Years as a Class Secretary

JUNE 1959 By CHARLES C. MERRILL '94 -

Feature

FeatureThe Trustees: 15 men and a woman with ultimate authority

October 1979 By Dan Nelson -

Cover Story

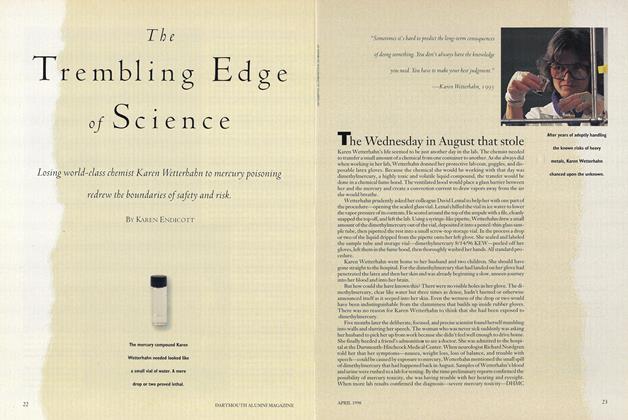

Cover StoryThe Trembling Edge Of Science

APRIL 1998 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

FeatureMusic

MAY 1957 By PROF. JAMES A. SYKES -

Feature

FeatureThe Day I Got Chewed Out By Red Blaik

NOVEMBER 1989 By Rodger S. Harrison '39