IN ITS RECENT PLANNING EFFORT, DARTMOUTH looked in the mirror and liked what it saw. This seems surprising mostly to Dartmouth people, who are notorious for comparing the College unfavorably with its competition. As for the competition, well, it seems as though it is trying to be more like Dartmouth or despairing of ever being as good. Examples:

The small college: At Middlebury College, in the middle of Vermont, stands a modern-looking science building. Outer doors on the second and third stories lead to nowhere; if you managed to unlock those doors you would fall straight down. They were to have been connected to other buildings to form a state-of-the-art science center. But the other buildings planned during the optimistic sixties—were never built. Now, while discoveries in the hard sciences are burgeoning, Middlebury is unable to attract grant money and the accompanying top scientists. The doors leading to nowhere reflect the little college's reluctant acceptance of its role: to offer excellent, personalized instruction in the sciences, a step or two back from the frontier. Meanwhile, Dartmouth has started construction on a $28 million chemistry building.

The big research university: At massive Johns Hopkins, cutbacks in federal aid along with the increasing costs of administering research—have triggered a financial crisis. Departments are being slashed, and some undergraduate programs are in danger. Meanwhile, Dartmouth has cut back slightly to put itself in fighting trim for a capital campaign.

At Syracuse, students have felt compelled to found an organization called Undergraduates for a Better Education to help lobby for their academic concerns. At Dartmouth, at least at the present, such a group would be unthinkable.

The Ivy competition: Henry Rosovsky, the eminent former dean of Harvard's undergraduate faculty, calls for a new commitment to teaching in universities. That is something Dartmouth never abandoned.

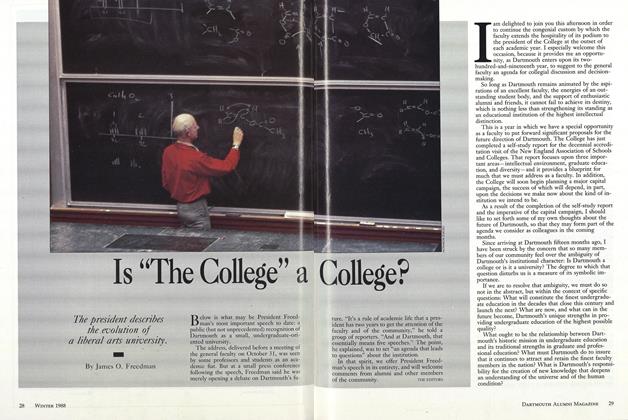

With all that Dartmouth has going for it, why form a College-wide planning committee? In fact, the committee devotes most of its 147-page report to planning ways not to change, to maintain Dartmouth's pre-eminence in its traditional strengths to chew, in effect, what it has already bitten off.

There is one area where the committee bites a bit deeper, however: graduate studies. If there is one subject that raises the hairs on the alumni neck (undergraduate alumni, that is), it is the notion of Dartmouth becoming a university and training Ph.D.s. But the fact is, Dartmouth already has been training Ph.D.s, and, in the sciences, has been doing so for decades. That's not to say that Dartmouth has been doing a good job of it. With a few glorious exceptions, the College's graduate programs have not come close to achieving the stature of the undergraduate and professional schools. With its report, Provost John Strohbehn's Planning Steering Committee has insisted that graduate studies measure up to the rest of the College. Do each program right, the report says, or consider not doing it at all.

All of which sounds eminently sensible.

But what is to keep "improvements" in the sciences from becoming a zero-sum game, robbing the undergraduate to pay the graduate? Officials reply that a good graduate student can bring in enough outside research funding to pay for his education. However, this self-funding works only when programs have the prestige and top professors that attract money from foundations, corporations, and the government. What should Dartmouth do with those programs that have little potential of measuring up? The obvious but in academia oh, so difficult answer is to kill them. To prevent the academic center of gravity from shifting irretrievably away from the undergraduate, the faculty must decide which graduate studies to keep, and which to shut down.

In other words, now for the really hard part: translating the planning committee's conservative principles into day-to-day operations. Dartmouth's enviable status depends on the outcome.

"As for the competition,well, it seems asthough it is tryingto be more likeDartmouth ordespairing of everbeing as good."

Its a niche thatother schoolswould die for.Can Dartmouthhang onto it?

"To prevent theacademic centerof gravityfrom shiftingirretiievably awayfrom theundergraduate,the faculty mustdecide whichgraduate studiesto keep, and whichto shutdown."

Jay Heinrichs is the editor of this magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe End of The Story

February 1991 By Dan Nelson '75 -

Feature

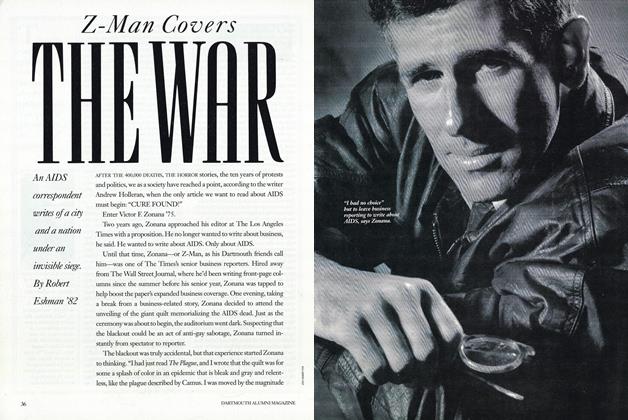

FeatureZ-Man Covers The War

February 1991 By Robert Eshman '82 -

Feature

FeatureOUR PASSIONATE PREFERENCE

February 1991 By Joseph D. Mathewson '55 -

Feature

FeatureWHO OWNS DARTMOUTH?

February 1991 By Joe Boldt '32 -

Feature

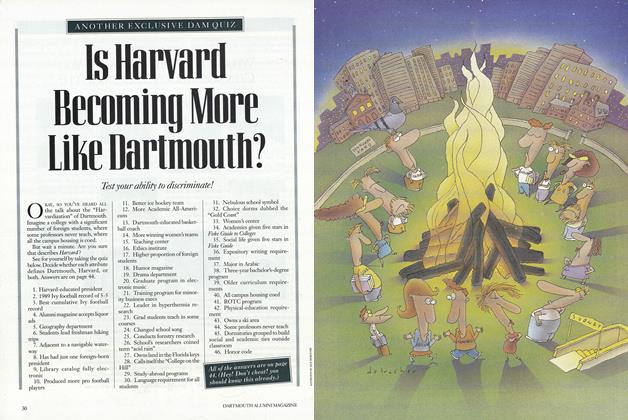

FeatureIs Harvard Becoming More Like Dartmouth?

February 1991 -

Feature

FeatureWe asked some students: WHAT ONE THING WOULD YOU CHANGE ABOUT DARTMOUTH?

February 1991

Jay Heinrichs

-

Article

ArticleProfessor William Cole: "Fifty Years From Now They'll Be Talking About This Course"

MAY • 1988 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureIS DARTMOUTH STILL DARTMOUTH?

SEPTEMBER 1988 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleA Poet in The Cosmos

NOVEMBER 1993 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleYour Breath Smells So Bad People on the Phone Hang Up.

November 1994 By Jay Heinrichs -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Night Out on the Net

December 1994 By Jay Heinrichs -

Outside

OutsideRunning With Wild Abandon

July/Aug 2002 By Jay Heinrichs

Features

-

Feature

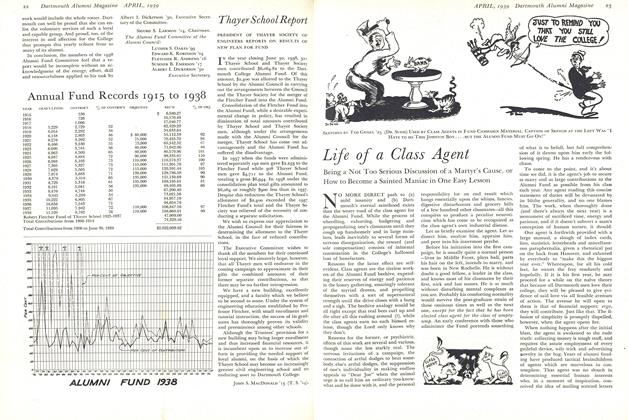

FeatureAnnual Fund Records 1915 to 1938

April 1939 -

Feature

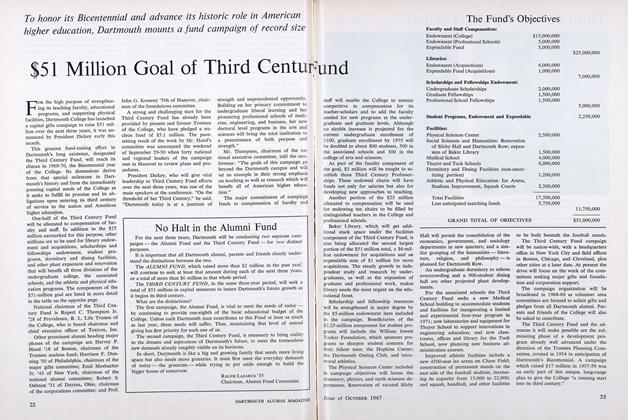

Feature$51 Million Goal of Third Century

OCTOBER 1967 -

Feature

FeatureReunion Week: Fun Plus Education

JULY 1968 -

Feature

Feature"The Working of the Religious Element"

October 1954 By GEORGE H. COLTON '35 -

COVER STORY

COVER STORYLifesaver

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2017 By Irene M. Wielawski