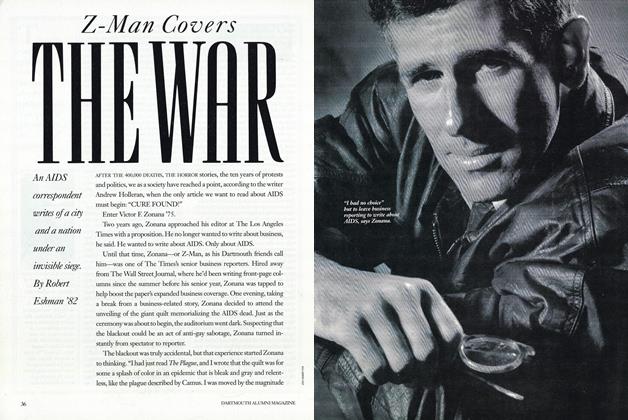

Lisa Conte '81 wants to save the rainforest, cure the flu, and make her company a lot of money.

ABOUT THREE YEARS AGO, Lisa Conte '81, T'85 needed some excitement in her work. With a B.A. in biochemistry from Dartmouth, an M.B.A. from Tuck, and a master's in applied physiology and pharmacology from U.C. San Diego, doing desk-bound research for a venture-capital firm just wasn't enough of a stretch. So she started her own company. These days, if all goes according to plan, the company Conte founded will: 1) rescue the wisdom of vanishing tribes; 2) help save the rainforest; 3) make hundreds of millions of dollars; 4) bring jobs and money to developing countries; and 5) cure the flu. Now that's a job.

Conte is founder and president of Shaman Pharmaceuticals, Inc., a San Carlos, California-based drug company that searches out traditional healing plants from rainforests around the world and refines them to create new medicinal compounds.

Dozens of Shaman's ethnobotanists and physicians travel rainforests from Brazil to Madagascar. They learn what plants the locals use, then send samples back to the company's state-of-the-art lab. There, a series of high-tech tests and experiments isolate what the pill labels call "active ingredients." Of the 800 plants Shaman researchers have found each year in the field, about 100 have been tested in the lab. Half of these have yielded promising new drugs, and three of those have patents pending: an anti-fungal drug that could be used to treat secondary infections in AIDS and cancer patients, an anti-viral compound that treats respiratory infections like influenza, and a topical antiherpes agent. The last two drugs are now in human clinical trials.

Not bad for an idea conceived in an office reception area. While waiting for a meeting to start, Conte began thumbing through a journal article on drug development. A receptionist came out and plopped another magazine on the table beside her. Its cover story was on the vanishing rainforest. Light bulbs and thunderclaps; the next day, Conte quit her job. "The idea was to take the rather academic and rarefied field of ethnobotany the cultural use of plants out of the lab and into the portfolio," said Conte. "I always had a lot of bright ideas and I'd half-try them. But I never really jumped off the cliff. With this I had no fear, no misgivings."

Evidently not. The initial financing for Shaman came from $40,000 Conte charged on 15 credit cards. She quickly ran through her life savings. Then her old employer invested $300,000 in seed capital, and Conte eventually raised more than $27 million; the company has since gone public. Shaman grew into a small, serious pharmaceutical concern of 37 employees. Her parents weren't crazy about the company's nonWall Street name but offered advice and moral support. Both pharmacists on Long Island, they understood that nearly 25 percent of all prescription drugs derive from plants.

In fact, most of the world's 265,000 known plant species are found in the rainforests, but fewer than one percent have been tested for their healing properties. An estimated 40,000 are believed to have undiscovered medicinal or nutritional value for humans. Merck, Eli Lilly, and other capital-rich drug giants understand that well, and they too have begun to explore what may be the world's greatest medicine chest.

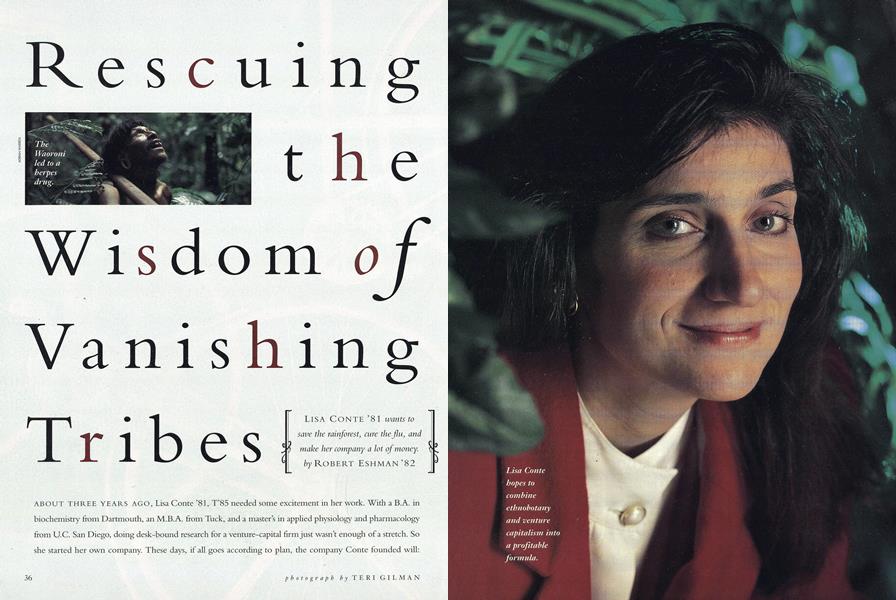

Conte's strategy is to outrun the Goliaths in the field, using top ethnobotanists and M.D.s to work directly with local shamans and healers. In one case, Shaman researchers noticed that a particular plant wellknown for its healing properties was chosen by the proverbial nine out of ten natives over modern antibiotics available in their village markets. The researchers deduced that the plant must also have anti-viral properties. Back in the lab, a compound in the plant was indeed found to be effective against viral respiratory illnesses, like influenza. The same plant was also used by the Waoroni tribe in Ecuador and Peru to heal wounds. Shaman researchers in the field pulled out some heavy medical tomes, the kinds with the lunch-defying pictures, and asked the Waoroni healers shamans to indicate the kind of wounds the plant cures. The healers pointed to pictures of Herpes sores. The compounds derived from that plant, known collectively as SP-303, are now in human clinical testing. Conte is confident that in two years, Shaman will own a drug that treats herpes and cures the flu.

This fieldwork approach can be time and labor intensive, but there is a payoff: if SP-303 proves successful, analysts predict that when the drug hits the market in 1995, Shaman Pharmaceuticals will reap hundreds of millions of dollars in sales.

Though Conte stresses that Shaman is first and foremost a profit-oriented drug company, she doesn't hide its other agenda. (In fact, the bright, jungle-print lab coats she designed for her technicians fairly scream it out.) Every second, an acre of rainforest is destroyed through logging, development, or grazing. Conte hopes governments will see the bottom-line logic of conserving the forests and the people who live there.

will only sign supply contracts with the indigenous people. Whether the company synthesizes its discoveries or pays native people to raise or harvest the plants from which they derive, Shaman plans to pump money back into rainforest conservation through a non-profit foundation it founded, the Healing Forest Conservancy. "The idea is to save not just the plants but the knowledge," Conte says. "In the old days tribal wisdom was passed on from generation to generation. Now it's being lost. Shaman won't save the rainforest, but it will have some impact."

It is the environmental angle that has attracted writeups in Forbes, Time, and numerous other magazines. "Three years ago people thought Shaman was voodoo medicine," Conte recalls. "Now there's greater respect being given to the value of traditional knowledge."

Greater respect, but still no especially exotic excitement. The former Dartmouth Outing Club member's dream of trekking the rainforests as the Indiana Jones of CEOs has fallen victim to Shaman's success. "I thought I'd travel a lot," she says wistfully. "But I just go from the lab to my otfice."

The Waoroni led to a herpes drug.

Lisa Conte hopes to combine ethnobotany and venture capitalism into a profitable formula.

Shaman Researchers noticed that a particular plant well-known for its healing properties was chosen by the proverbial nine out of ten natives.

Writer Rob Eshnan lives in Los Angeles.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThis Man Scanndalized Eleazar Wheelock

June 1993 By Jerold Wikoff -

Feature

FeatureTHE PEMI AFFAIR

June 1993 By KIRK SIEGEL'82 -

Feature

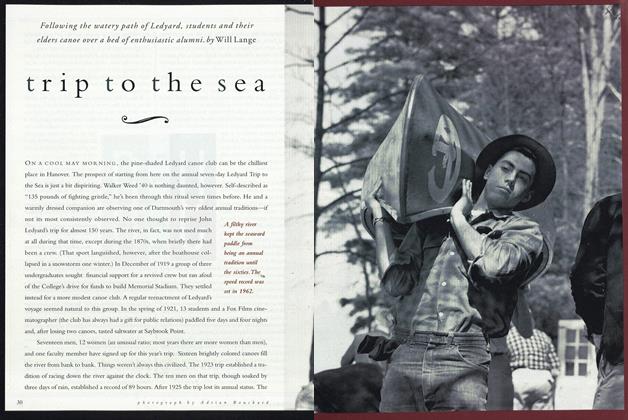

FeatureTrip to the sea

June 1993 By Will Lange -

Feature

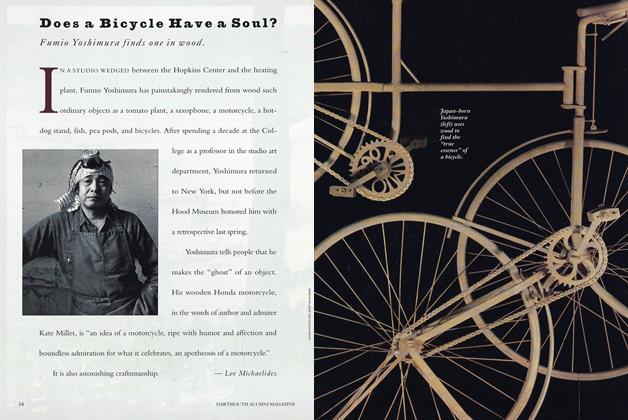

FeatureDoes a Bicycle Have a Soul?

June 1993 By Lee Michaelides -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

June 1993 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleMaking the Walls Talk

June 1993 By Karen Endicott

Robert Eshman '82

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

JULY 1968 -

Feature

FeatureTo Screenwriting Born

November 1982 By Budd Schulberg '36 -

Feature

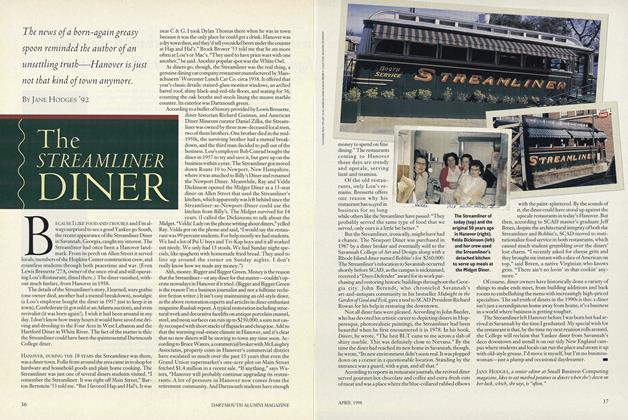

FeatureThe STREAMLINER DINER

APRIL 1998 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Feature

Feature1340 on your radio dial

APRIL 1983 By John May '85 -

Feature

FeatureANCIENT PAGE TURNERS

MARCH 1990 By JONI COLE AND LEE MICHAELIDES -

Feature

FeatureOne on One

MARCH 2000 By Mel Allen