"Twentieth-century literature responds to a crisis in meaning." Elaborate in 500 words or less.

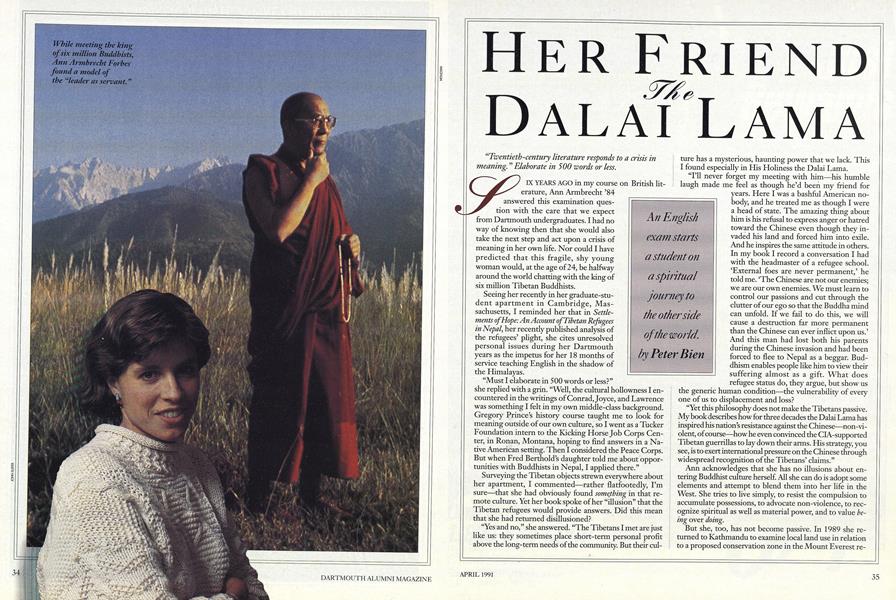

Six years ago in my course on British literature, Ann Armbrecht '84 answered this examination question with the care that we expect from Dartmouth undergraduates. I had no way of knowing then that she would also take the next step and act upon a crisis of meaning in her own life. Nor could I have predicted that this fragile, shy young woman would, at the age of 24, be halfway around the world chatting with the king of six million Tibetan Buddhists.

Seeing her recently in her graduate-student apartment in Cambridge, Massachusetts, I reminded her that in Settlements of Hope: An Account of Tibetan Refugeesin Nepal, her recently published analysis of the refugees' plight, she cites unresolved personal issues during her Dartmouth years as the impetus for her 18 months of service teaching English in the shadow of the Himalayas.

"Must I elaborate in 500 words or less?" she replied with a grin. "Well, the cultural hollowness I encountered in the writings of Conrad Joyce, and Lawrence was something I felt in my own middle-class background. Gregory Prince's history course taught me to look for meaning outside of our own culture, so I went as a Tucker Foundation intern to the Kicking Horse Job Corps Center, in Ronan, Montana, hoping to find answers in a Native American setting. Then I considered the Peace Corps. But when Fred Berthold's daughter told me about opportunities with Buddhists in Nepal, I applied there." Surveying the Tibetan objects strewn everywhere about her apartment, I commented—rather flatfootedly, I'm sure—that she had obviously found something in that remote culture. Yet her book spoke of her "illusion" that the Tibetan refugees would provide answers. Did this mean that she had returned disillusioned?

"Yes and no," she answered. "The Tibetans I met are just like us: they sometimes place short-term personal profit above the long-term needs of the community. But their culture has a mysterious, haunting power that we lack. This I found especially in His Holiness the Dalai Lama.

"I'll never forget my meeting with him—his humble laugh made me feel as though he'd been my friend for years. Here I was a bashful American nobody, and he treated me as though I were a head of state. The amazing thing about him is his refusal to express anger or hatred toward the Chinese even though they invaded his land and forced him into exile. And he inspires the same attitude in others. In my book I record a conversation I had with the headmaster of a refugee school. 'External foes are never permanent,' he told me. 'The Chinese are not our enemies; we are our own enemies. We must learn to control our passions and cut through the clutter of our ego so that the Buddha mind can unfold. If we fail to do this, we will cause a destruction far more permanent than the Chinese can ever inflict upon us.' And this man had lost both his parents during the Chinese invasion and had been forced to flee to Nepal as a beggar. Buddhism enables people like him to view their suffering almost as a gift. What does refugee status do, they argue, but show us the generic human condition—the vulnerability of every one of us to displacement and loss?

"Yet this philosophy does not make the Tibetans passive. My book describes how for three decades the Dalai Lama has inspired his nation's resistance against the Chinese—non-violent, of course—how he even convinced the CIA-supported Tibetan guerrillas to lay down their arms. His strategy, you see, is to exert international pressure on the Chinese through widespread recognition of the Tibetans' claims."

Ann acknowledges that she has no illusions about entering Buddhist culture herself. All she can do is adopt some elements and attempt to blend them into her life in the West. She tries to live simply, to resist the compulsion to accumulate possessions, to advocate non-violence, to recognize spiritual as well as material power, and to value being over doing.

But she, too, has not become passive. In 1989 she returned to Kathmandu to examine local land use in relation to a proposed conservation zone in the Mount Everest regions of Nepal and Tibet. This year she is continuing her investigation of how this idea intersects with the needs of local inhabitants. After completing a doctorate in social anthropology at Harvard, she expects to collaborate with her husband, Peter Forbes '83, on promoting U.S. conservation zones that safeguard cultural as well as natural values.

"Let's bring the discussion back to Dartmouth," I suggested. "During your undergraduate years you became aware of a personal crisis in meaning. This led you to seek answers througan internship and then, after graduation, through a service opportunity that you could never have predicted in your freshman year. The same route has been followed by other Dartmouth students, of course. I think of Steve Wheeler, who preceded you as a Tucker intern at Kicking Horse and then spent a decade in Washington working at subsistence pay for environmental lobbies; he has just completed a book called Twelve Modest Proposals for a Healthier Society. Then there's Katy Van Dusen—she interned in Jersey City, received Tucker's top award for service to others, went from Dartmouth to a Costa Rican Quaker community that functions as a model agricultural station for its region, returned to finish graduate training at Cornell, and has now settled again in Costa Rica. A more recent example is Yanna Yannakakis, who did her Tucker internship with Amnesty International and is presently in Washington raising funds for Guatemalan war widows. And we sent Eric Fanning to Atlanta last year to intern at the Carter Center, where he helped lay the groundwork for Ethiopian peace negotiations."

I informed Ann in addition that Dartmouth now has a faculty group working to foster regional zones of international cooperation—precisely what the Dalai Lama advocated in his Nobel lecture last December. "And did you know," I continued, "that James O. Freedman, along with the presidents of MIT, Pennsylvania, Tufts, Notre Dame, and Hampshire, is one of the six original American signers of the Talloires Declaration? This is a document in which 34 university presidents from around the world affirm that institutions of higher learning have a moral responsibility to foster understanding of the awful risks of the nuclear age and to reduce those risks. 'Peace as a concept,' they declare, 'must be in our students' imaginations, in their intellects, and in their lives.'"

Finally, I told Ann the good news that it was Dartmouth's emerita professor Elise Boulding who founded the International Peace Research Association 25 years ago. It is largely owing to her work that today there are hundreds of Peace Studies programs in universities around the world, including Dartmouth.

"In other words," Ann responded, "it seems that more and more students and faculty at Dartmouth are attracted, as I am, to the Dalai Lama's principle of non-violence and to his dream that mankind will learn how to communicate heart to heart through service. When I was at Dartmouth I heard a lot about the College's mission to produce leaders. Leaders are fine. But 18 months with Tibetan Buddhists taught me that servants, too, are fine. My ideal Dartmouth would be a producer of servants."

I reflected that Ann Armbrecht Forbes had discovered in her friend the Dalai Lama an extraordinary example of the leader as servant. Is it regrettable that she needed to go halfway around the world to make this discovery? Certainly not. We could perhaps wish that our students might encounter not only ultimate questions during their undergraduate years, but also some ultimate or near-ultimate answers. Yet if we graduate others like Ann who actively seek such answers outside the academy, is that so very bad?

While meeting the king of six million Buddhists, Ann Armbrecht Forbes found a model of the "leader as servant."

An English exam starts a student on a spiritual journey to the other side of the world.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

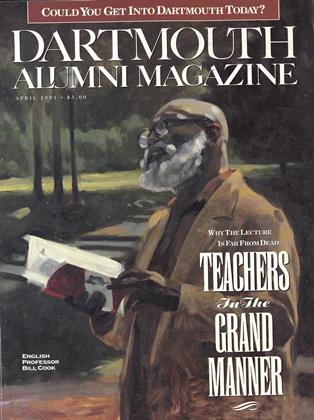

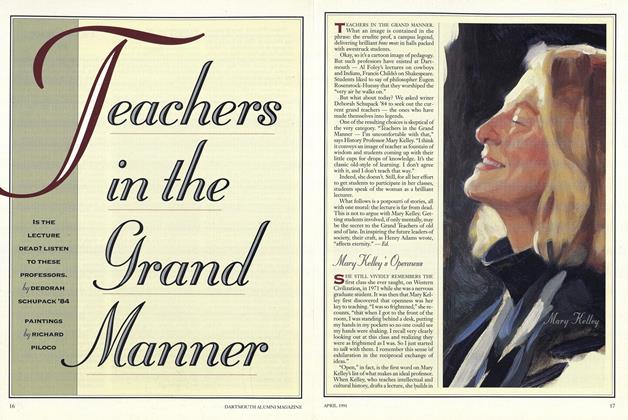

Cover StoryTeachers in the Grand Manner

April 1991 By DEBORAH SCHUPACK '84 -

Feature

FeatureA Recent Interview with Ernest Martin Hopkins' 01

April 1991 -

Feature

FeatureSTEVE KELLEY IN TWO ACTS

April 1991 By ROBERT ESHMAN '82 -

Feature

FeatureCOULD I GET IN TODAY?

April 1991 -

Feature

FeatureDisengagement

April 1991 By John Sloan Dickey '29 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

April 1991 By E. Wheelock

Features

-

Feature

FeatureAcademic Centers

June 1980 -

Feature

FeatureDean Shanahan: Five Concerns

December 1987 -

Feature

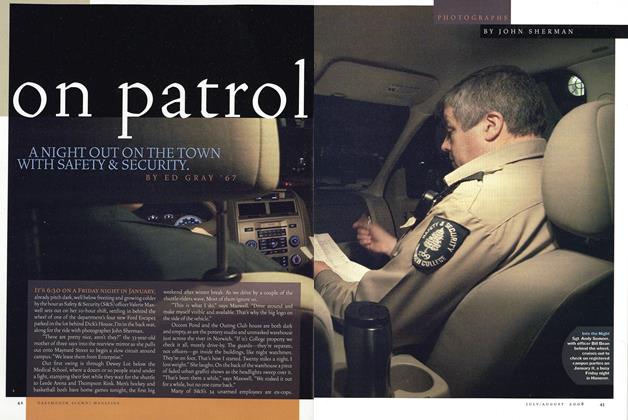

FeatureOn Patrol

July/August 2008 By ED GRAY ’67 -

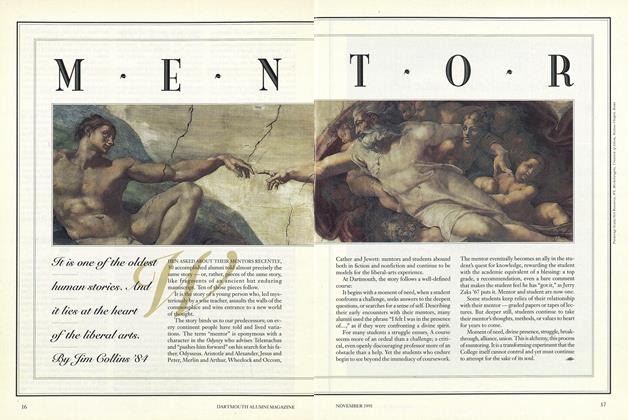

Cover Story

Cover StoryMENTOR

NOVEMBER 1991 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

FeatureThe Surrogacy Option

September | October 2013 By Lisa baker ’89 -

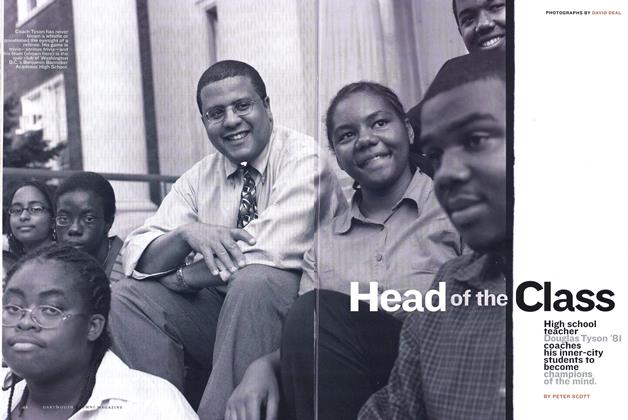

Cover Story

Cover StoryHead of the Class

Nov/Dec 2002 By PETER SCOTT