A Status Report on a 228-Year-Old Mission

BEFORE FOUNDING DARTMOUTH in 1769, Eleazar Wheelock had spent 15 years educating Indians to spread Christianity among Native peoples. Frustrated by dwindling enrollments at his Moors Charity School, though, and dispirited that his vision was more complicated than he originally believed, by the time Wheelock opened, Dartmouth, he had changed his focus to educating "English youths, and any others" for die Indian mission work. Although Indian education lived on in the College charter, during the next 200 years only 120 Indians attended the school. Of history professor Jere Daniell '55, only nine appear to have graduated.

When John Kemenv became president of Dartmouth in 1970 he went back to the charter. He instructed the College to actively recruit Native students and provide a support system to "make these students feel a part of the Dartmouth family." in 1972 he hired anthropologist Michael Dorris, a Modoc, to launch Native American Studies. During the next 25 years the interdisciplinary offerings matured into a fully realized field with a minor and more than a dozen courses spanning anthropology, history, religion, linguistics, literature, and film studies. More than 350 Native students have studied at Dartmouth since 1970. Current enrollments stand at 119 undergraduates and ten grad students.

These students and Dartmouth are defying the odds against Native Americans earning diplomas. Nationally only ten percent of Native college students complete their educations. At Dartmouth roughly 72 percent of Indians finish theirs. According to Michael Hanitchak '73, director of the Native American Program, Dartmouth selects strong students and works to keep them strong. Even Dartmouth's isolation from most Native communities contributes to their educational success. Students can't just leave on the spur of a discouraging moment, says Hanitchak. "It's not so easy to get home from here."

For many Native students Dartmouth is an environment unlike any they have known before. The Native American Program's visiting artisans, spiritual and political leaders, and family guests help create an on-campus community similar to students'home communities. Weekly discussion groups, a student-run, confidential, sacred support group called Talking Circle, and faculty dinners at the Native American House on North Main Street provide gathering places for many Native students. The community of Native Americans at Dart mouth (NAD) is, in many cases, the first encounter students have with Native peoples from other traditions.

Finding ties to the wider Dartmouth community is tough for some students, says Hantichak He spends "a lot of time" encouraging Native students to talk to their professors. "In Native society education, healing, advice, and support

all come from the same group of people," he says. "The idea that strangers provide those services is not prevalent." Arguing that "the entire institution has to be involved in the education of Indians," he challenges the College: "Is Dartmouth committed to Indian education or to simply having some Indians going to school here?"

Increasing the Native presence in the academic life of the College is the mission of Native American Studies, the academic program Michael Dorris established. According to Colin Calloway, professor of history and Native American Studies and the John Sloan Dickey Third Century Professor in the Social Sciences, the academic program deals with issues important to Native American people, but also teaches nonIndians about Native life. In fact, some 75 percent of students in Native American Studies courses are non-Indian. Calloway says that he tries to create a classroom environment where both Natives and non-Natives "'feel comfortable" by making room '"for multiple perspectives on difficult issues." For example, he says, "It's easy to look back on history and see the hard things and fall into the trap of assigning blame. That doesn't really help us understand the past. The past is a complicated place."

Says Native American Studies chair and anthropology professor Sergei Kan, contemporary issues such as tribal sovereignty, repatriation of artifacts, and a growing desire of Indian people to represent themselves through Natives-only scholarship cry out for dialogue. Calloway is offering grants from his Dickey professorship to encourage professors to include Native American issues and perspectives in an increasing pool of classes. So far, sociologist Misagh Parsa has incorporated the American Indian:power movement in his course on late twentieth-century social movements and geographer Frank Magilligan has included Indian water rights in me West in courses on water and environmentalissues. Calloway would like to see economics, government, and sociology classes take up the question of what happens to communities that experience massive influxes of health—as with casinos—and how the changes reverberate through the wider community, right through'to the state and federal legislative levels. Increasingly. "Native American Studies is a reference point for Other departments." says Kan. Dartmouth is rapidly becoming known as the eastern center for serious Native American scholarship. "Even in the West there is respect for this program." he says.

In making good on Dartmouth's charter, the College is trying to do more than resetting Wheelock's vision. It is working to bring Native America into clearer focus for Dartmouth and all its students.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryI Have Come This Far

April 1997 By Robert A. Bennett '93 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWhy Don't You Say Anything?"

April 1997 By Davina Begaye Two Bears '90 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMy Grub Box

April 1997 By Vivian Johnson '86 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryI Dance for Me

April 1997 By Elizabeth Carey '93 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWe Are Not Your Indians

April 1997 By Arvo Mikkanen '83 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"You'll Know What to Do"

April 1997 By Bruce Duthu '80

Karen Endicott

-

Article

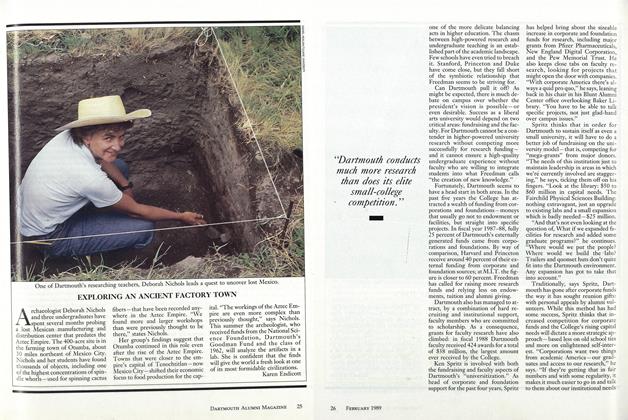

ArticleEXPLORING AN ANCIENT FACTORY TOWN

FEBRUARY 1989 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleJoining the Queue

May 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleOut of the Literary Closet

NOVEMBER 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleThe City Peter Built

Winter 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleControlling Self-Control

December 1995 By Karen Endicott -

CLASSROOM

CLASSROOMCode of Life, Codes of Conduct

Sept/Oct 2000 By Karen Endicott

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryDavid Shula '80

March 1993 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryOCCOM’S DIARY

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureMaking Music

November 1978 By Dana Grossman -

Feature

FeatureKenneth Allan Robinson

February 1962 By F. CUDWORTH FLINT -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to the College

JULY 1967 By STEVE GUCH JR. '67 -

Feature

FeatureExciting Theater Ahead

MAY 1957 By WARNER BENTLEY