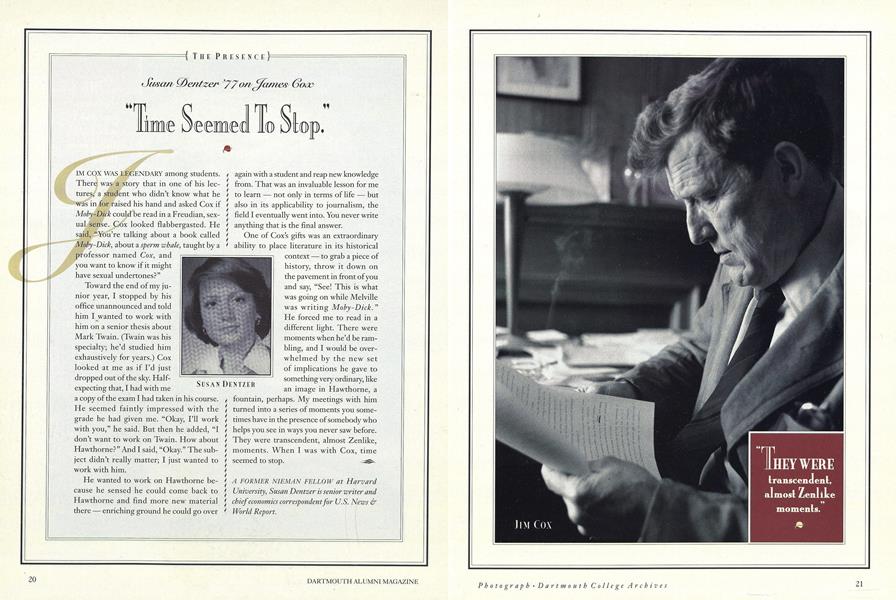

IM COX WAS LEGENDARY among students. There was a story that in one of his lectures, a student who didn't know what he was in for raised his hand and asked Cox if Moby-Dick could be read in a Freudian, sexual sense. Cox looked flabbergasted. He said, "You're talking about a book called Moby-Dick, about a sperm whale, taught by a professor named Cox, and you want to know if it might have sexual undertones?"

Toward the end of my junior year, I stopped by his office unannounced and told him I wanted to work with him on a senior thesis about Mark Twain. (Twain was his specialty; he'd studied him exhaustively for years.) Cox looked at me as if I'd just dropped out of the sky. Half-expecting that, I had with me a copy of the exam I had taken in his course. He seemed faintly impressed with the grade he had given me. "Okay, I'll work with you," he said. But then he added, "I don't want to work on Twain. How about Hawthorne?" And I said, "Okay." The subject didn't really matter; I just wanted to work with him.

He wanted to work on Hawthorne because he sensed he could come back to Hawthorne and find more new material there enriching ground he could go over

again with a student and reap new knowledge from. That was an invaluable lesson for me to learn not only in terms of life but also in its applicability to journalism, the field I eventually went into. You never write anything that is the final answer.

One of Cox's gifts was an extraordinary ability to place literature in its historical context to grab a piece of history, throw it down on the pavement in front of you and say, "See! This is what was going on while Melville was writing Moby-Dick." He forced me to read in a different light. There were moments when he'd be rambling, and I would be overwhelmed by the new set of implications he gave to something very ordinary, like an image in Hawthorne, a fountain, perhaps. My meetings with him turned into a series of moments you sometimes have in the presence of somebody who helps you see in ways you never saw before. They were transcendent, almost Zenlike moments. When I was with Cox, time seemed to stop.

Susan Dentzer

"They were transcendent, almost Zenlike moments."

A FORMER NIEMAN FELLOW at HarvardUniversity, Susan Dentzer is senior writer andchief economics correspondent for U.S. News &World Report.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

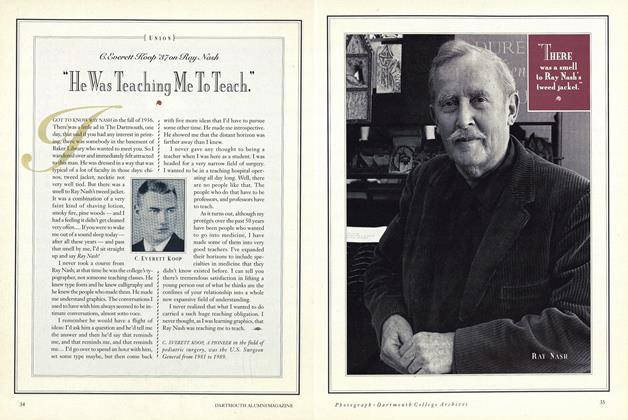

FeatureC. Everett Koop '37 on Ray Nash

November 1991 By Ray Nash -

Feature

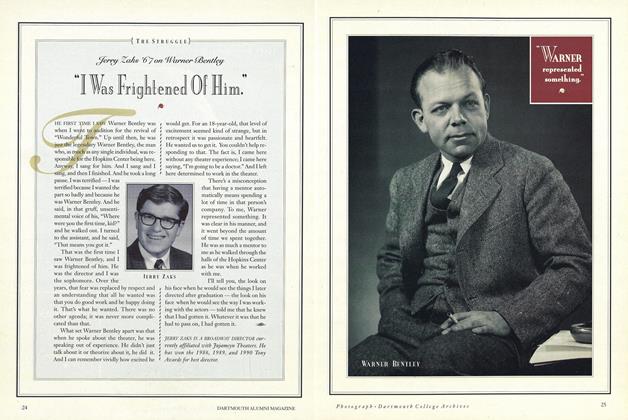

FeatureJerry Zaks '67 on Warner Bentley

November 1991 By Warner Bentley -

Feature

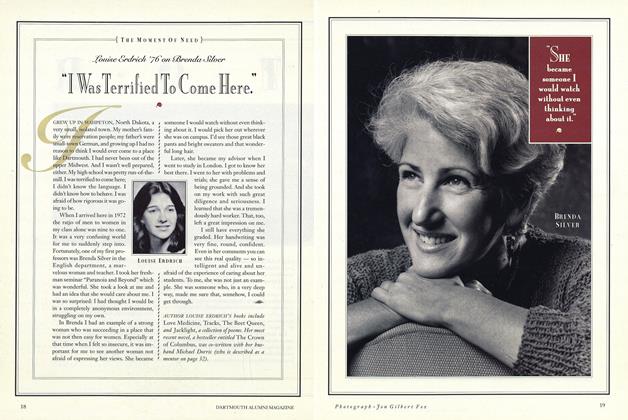

FeatureLouise Erdrich '76 on Brenda Silver

November 1991 By Brenda Silver -

Feature

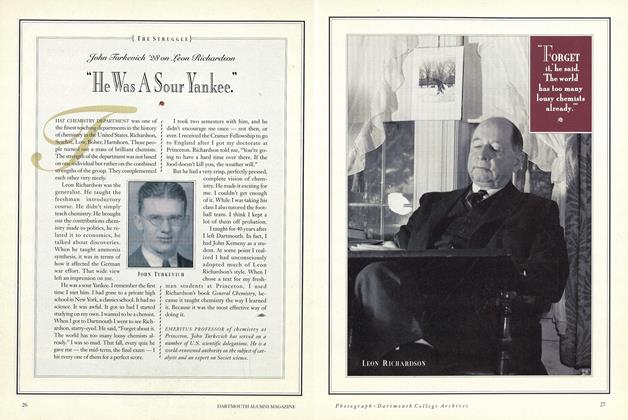

FeatureJohn Turkevich '28 on Leon Richardson

November 1991 By Leon Richardson -

Feature

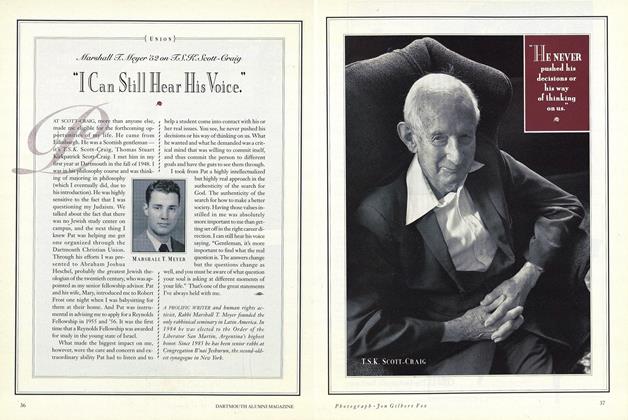

FeatureMarshall T. Meyer '52 on T.S.K. Scott-Craig

November 1991 By T.S.K. Scott-Craig -

Feature

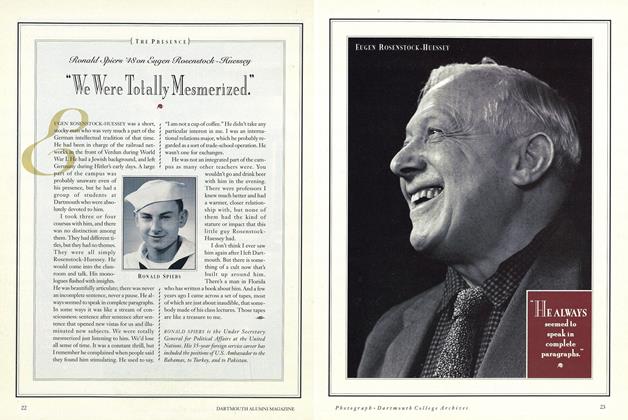

FeatureRonald Spiers '48 on Eugen Rosenstock-Huessey

November 1991 By Eugen Rosenstock-Huessey