In our quick-change society, college nostalgia links us to ourselves.

One of the more notable idiosyncrasies of American culture is the phenomenon of "going to college" where young people spend four years trying to figure out what to be "when they grow up." Paradoxically, they of ten do this by studying subjects far removed from what they will actually do after graduation. Equally striking is the desire of many people to prolong the college experience through alumni magazines, reunions, football games. What is it that makes college so important in American culture, and what is it about American culture that makes college so essential to recall and revisit from time to time?

The first notable thing about college is that so many people throughout the world get along without it. The Maya Indians I worked with in Guatemala learn from an early age much of what life promises: they will live in dirtfloored adobe houses; they will marry as teenagers, begin families, and probably see at least one child die in infancy; most will farm for a living, hoeing small plots of corn scattered over rugged mountainsides; many will supplement scanty harvests with meager wages from seasonal work on coffee and cotton plantations; all but a few will be poor, their primary concern not what to be when they grow up but how to get by as their parents have.

Living predictable if precarious lives among lifelong friends and neighbors gives these Maya shared values and mutually recognized milestones by which to measure life's progress. Americans share few such certainties. Rather than following in our parents' footsteps, we are expected to leave home, get a job, and "make something" of ourselves. Although we cherish the freedom to choose a career and take pride in our opportunistic mobility, such autonomy simply makes a virtue of necessity: the vagaries of a market economy may compel us toward different possibilities than our parents knew, but we also have no choice but to sell whatever we can make or do to make ends meet.A society-wide ethic of free agency makes most of us incidental, often anonymous, associates in each other's careers. Ironically, such individual self-absorption threatens to erode any common social purpose beyond personal interests of family, friends, and colleagues, just as it breeds the insidious assumption that we have no one to blame but ourselves if we fail.

For those who can afford it, college represents the first step in our quest for personal security in an impersonal world. This reveals a second curiosity about college: although ideally it prepares young Americans for productive, meaningful lives, the varied lives it prepares them for preclude a universal, set course of study. Rather than mastering specific skills or a single curriculum, students spend much of their time learning how to learn through a multiplicity of disciplines. Unlike my Maya friends, they must discover how to "do your own thing" without knowing what they will do or be as adults or even when they have finally "grown up."

Many cultures resolve the ambiguities of finding one's place in the world through what anthropologists call "rites of passage," formal initiation rituals that publicly bestow adulthood on their youth. Rites of passage often physically isolate initiates from normal community life, reveal to them tribal mysteries and lore, then reintroduce them into the community, formally if not quite in fact ready to assume the responsibilities of full adults. College represents such a rite of passage: for four years students live in a "liminal" state as anthropologist Victor Turner dubbed these periods of magical transition betwixt and between the familial constraints of adolescence and the demands and duties of the real world. Theirs is a Peter Pan existence forever 18 to 22 years old, full of self-importance but free of wider import, where only the books, the buildings, and the faculty age.

As with most liminal periods, college combines alternating doses of discipline and license. Students endure the dictates of both professors and their peers. Under the pretense of choosing their own course of study, they are constantly told what to do and rewarded for doing it well. At the same time, students plumb the limits of drinking, sex,stress, deadlines, and living with their decisions as they develop ways of getting along in the world after college.

Ideally, this rite of passage takes place far from home, beyond the scrutiny of parents, neighbors, and old friends. It also involves a highly personal coming of age, shared in time with one's classmates, but chosen, pursued, and achieved individually.In both respects college reinforces the value of "making it on your own" in American culture through a four-year collective experience of leaving home.

After graduation, however, nothing tells us when we have finally "made it" in the real world. No syllabus guides us now, no course requirements dictate our tasks, no final grade defines success or failure. If personal satisfaction ultimately defines success, we could have always done more or better or differently. If personal security is the measure, changing fads and fashions cloud our prospects with nagging doubts of personal adequacy or worse, fears of personal obsolescence. Like sharks, American careers must constantly move forward or sink dead in the water.

Having worked so long and hard to grow up, we one day confront an incongruous world in which we suddenly feel that times are about to pass us by. We then begin to wonder what happened to the good old days, before we became what we are now, when other opportunities beckoned, when promise counted more than performance, when our best friends were friends of each other as well.If our college days prepare us for the real world, they also beckon us back once we get there.

Such nostalgia reflects more than longing for an irretrievable perhaps imaginary golden age of youth. It derives from a world so predicated on change that the times in which we grow up become outdated before we outgrow them. Nostalgia transforms impending anachronisms into a kind of lived history: in reminding us of "the good old days," it also reaffirms how much we have changed and grown since then. College reunions clearly express this kind of nostalgia. Like pilgrimages in our secular age, they draw us back across space and time, not to sacred relics, but to living touchstones of our adult selves. Collegiate nostalgists persevere not because they refuse to grow up but because, having grown up, they still find their college days meaningful. Long after college is over, it sustains a sense of belonging in lives fall of individual achievement but short on mutual recognition and collective satisfactions of shared place and past.

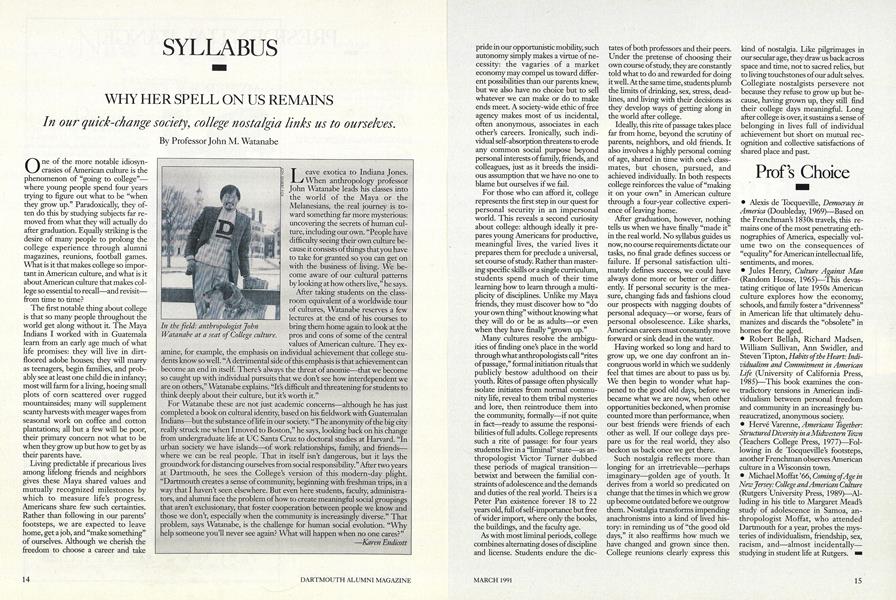

In the field: anthropologist John Watanabe at a seat of College culture.

Leave exotica to Indiana Jones. When anthropology professor John Watanabe leads his classes into the world of the Maya or the Melanesians, the real journey is to ward something far more mysterious: uncovering the secrets of human culture, including our own. "People have difficulty seeing their own culture because it consists of things that you have to take for granted so you can get on with the business of living. We become aware of our cultural patterns by looking at how others live," he says.

After taking students on the classroom equivalent of a worldwide tour of cultures, Watanabe reserves a few lectures at the end of his courses to bring them home again to look at the pros and cons of some of the central values of American culture. They examine, for example, the emphasis on individual achievement that college students know so well. "A detrimental side of this emphasis is that achievement can become an end in itself. There's always the threat of anomie that we become so caught up with individual pursuits that we don't see how interdependent we are on others," Watanabe explains. "It's difficult and threatening for students to think deeply about their culture, but it's worth it."

For Watanabe these are not just academic concerns—although he has just completed a book on cultural identity, based on his fieldwork with Guatemalan Indians—but the substance of life in our society. "The anonymity of the big city really struck me when I moved to Boston," he says, looking back on his change from undergraduate life at UC Santa Cruz to doctoral studies at Harvard. "In urban society we have islands—of work relationships, family, and friends— where we can be real people. That in itself isn't dangerous, but it lays the groundwork for distancing ourselves from social responsibility." After two years at Dartmouth, he sees the College's version of this modern-day plight. "Dartmouth creates a sense of community, beginning with freshman trips, in a way that I haven't seen elsewhere. But even here students, faculty, administra- tors, and alumni face the problem of how to create meaningful social groupings that aren't exclusionary, that foster cooperation between people we know and those we don't, especially when the community is increasingly diverse." That problem, says Watanabe, is the challenge for human social evolution. "Why help someone you'll never see again? What will happen when no one cares?" —Karen Endicott

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

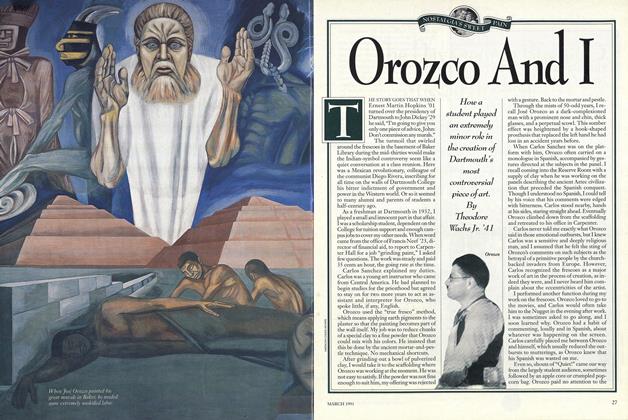

FeatureOrozco And I

March 1991 By Theodore Wachs Jr. '41 -

Cover Story

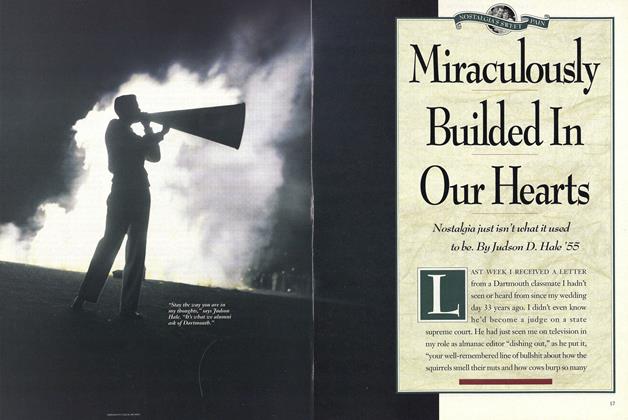

Cover StoryMiraculously Builded In Our Hearts

March 1991 By Judson D. Hale '55 -

Feature

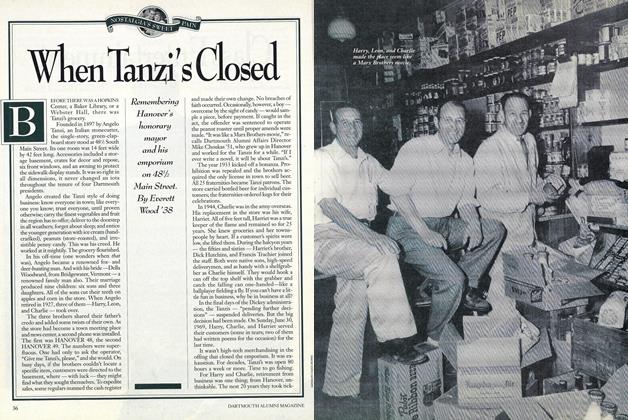

FeatureWhen Tanzi's Closed

March 1991 By Everett Wood '38 -

Feature

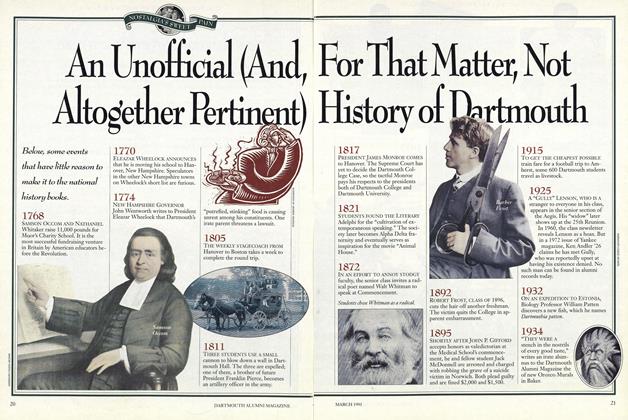

FeatureAn Unofficial (And, For That Matter, Not Altogether Pertinent) History of Dartmouth

March 1991 -

Feature

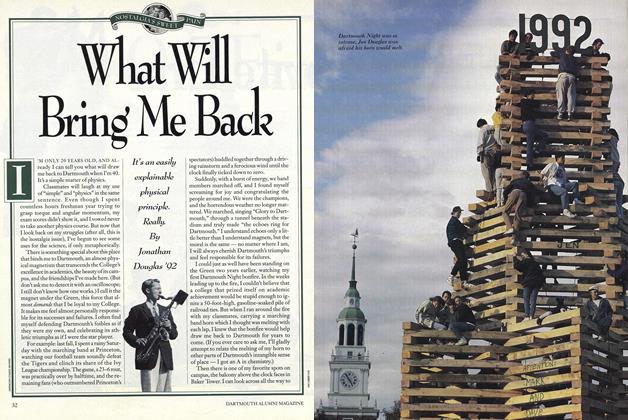

FeatureWhat Will Bring Me Back

March 1991 By Jonathan Douglas '92, Richard Hovey -

Feature

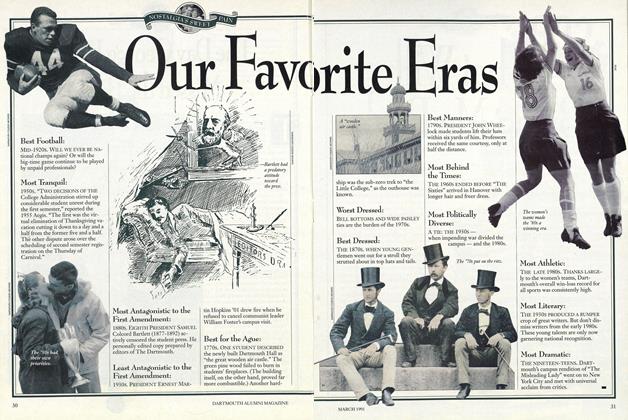

FeatureOur Favorite Eras

March 1991