A View of David Lambuth Whose Own Theories of Teaching Have Triumphed Through Many Years of Testing

LAST YEAR THE Tower Room of the Library advertised a talk on Wine:its History and Uses, by Professor David Lambuth. An undergraduate, glowering doubtfully at the bulletin board, was overheard to remark, "What the hell does he know about wine? I never saw him drunk in my life."

Professor Lambuth treasures that remark, not so much for its testimony to his spotless character as for its moral in pointing the need for a certain kind of teaching: his kind. It is one of many indications of his belief that a teacher of modern literature should be primarily concerned with the student's adjustment or maladjustment to his own world. Books that avoid the real problems of life do not particularly interest this professor. Books of the past, however great and enduring, are to him less useful implements in the art of teaching than books of the present, which force his students to choke a bit on the stringy, halfcooked meat of current problems: unsolved problems that young graduates will have to chew on in grim earnest nowadays.

He holds to the opinion, grown regrettably rare in liberal arts faculties, that it is a part of the business of teaching to stoke Carlyle's "fire in the belly" of the young. To him, education is a shoddy profession if it only indicates how best to cope with vext conditions for the sake of personal security and advancement. He has not said as much to me, but I think he would not be content to let any man pass through his classes without at least having been thoroughly exposed to the idea that personal defeat in an effort to better the world may be preferable to the materialistic philosophy of "I'll get mine."

I am stressing this point, first, to correct a prevalent misapprehension. Early in the chat which refreshed my memory for this sketch, its subject made the occasion to say defensively, "There's nothing Elizabethan about me." I pass the remark along without affirming it, because I do not believe it wholly accurate. There are, obviously, the wonderful whiskers, such as gladden many an Elizabethan portrait. There is a flair for good living, distinctly Elizabethan in "its connotations. Above all, David Lambuth is embued with the Elizabethan curiosity for searching out and knowing the currents of the current world. He is a kind of Hakluyt in Hanover, amassing the strange newes of the Voiagers and Travaillers.

seem to do, that he is mainly concerned with the Frobishers and Lithgows, the Marlowes and Chapmans: that is, with dead men. He knows Elizabethan history and literature as any competent member of an English faculty should know them; but in his teaching, they are a background for reference and comparison. His private interests, as well as his classroom emphases, grow out of our own living world of today. The mistake comes in thinking, as many His voyagers are John Steinbeck, steering a hopeless old jalopy to the promised Californian land, or Antoine de Saint Exupery, scraping the mountain cols as he flies the mail. Hanover's Hakluyt gathers together these realities of contemporary experience, and gives them their perspective against the comparable experiences of like men in other times.

Thus there is something Elizabethan about him, despite his protest. He views our own gusty, good-and-evil, blundering world with the same eye that the Elizabethans turned upon theirs.

I am at pains to make this point, because I do not suppose that Professor Lambuth has ever adequately tried to make it for himself. He is somewhat of a walking legend, and he knows it. He whips out an occasional phrase of protest, but he does not protest too much, or even enough. As a result, there have always been those who, seeing only the outward phenomena, have thought him a poseur who attained eminence on the faculty through flamboyant gestures impossible to ignore. I .tactlessly here set down these accusations for the pleasure of insisting that they are nonsense. Many of us would like to have the courage of our natural impulses. David Lambuth always has had the courage of his; and to express natural impulses, while it may at times be startling to the muddyminded, is certainly neither a pose nor a gesture.

The man is all of a piece. His clothes are tailored with distinctive features that may not suit Kuppenheimer; but they suit him, and he is the one who wears them. His Packard is the color of the best fresh dairy cream. It must take a lot of washing, but so must the cream-colored dinner jacket that matches it, and him. The dinner jacket, lest it imply too much purity, is lined with scarlet to harmonize with the good wine that finds it slow way into the interior of the wearer; but as another check upon perfection, he smokes a most lowly species of cigar.

All such apparent foibles grow logically out of the Lambuth background. It can be sketched in brief as follows, beginning with the great-great grandfather who left Virginia and wandered westward through Tennessee and Kentucky with Daniel Boone.

This ancestor was admired by Boone as a good shot with a squirrel rifle, but he was also a most powerful preacher, an excellence which Boone did not appreciate. Their ways parted, and the preaching thread was carried on by the squirrel-hunter's son, who went out to China in 1854 as a missionary, in the tea clipper Ariel. As a coincidence, a second missionary passenger on the same voyage was presently to become David Lambuth's other grandfather.

NATIONALITY COMPLICATIONS

Professor Lambuth's father was born in the British concession in Shanghai, which would seem to have made him either an American, an Englishman, or a Chinaman, according to your way of looking at it. To complicate matters further, David Lambuth himself was born, eventually, in the French concession. As nothing in a legal way was done about it, he has his choice of four nationalities; but he rather leans toward the opinion that he is a Frenchman.

Before dropping the complications of ancestry, I ought to point out that the maternal grandfather, apart from his efforts to convert the yellow heathen, also cast the fighting eyes of a reformer on the Damn-Yankees. He left China to return to the Civil War, and ended up as a Brigadier General with Bedford Forrest. His name was David Campbell Kelley. The question of ancestral strains thus is strained further by the fact that Kelley was an Irishman with a dash of Highland Scot to account for the Campbell. With that particular admixture in his veins, he had small patience for customary tactics. His chief achievement was to capture two Federal gunboats with his troop of cavalry.

This neatest trick of the war can be usefully remembered as a sort of symbol of the teaching methods of Brigadier General Kelley's grandson, a remark which I shall presently attempt to substantiate. The background, I ought to add, is not exclusively southern. It was a grandmother from upper New York who taught our hero his Three R's.

David Lambuth was born in 1879, passed a Chinese childhood, and came to the United States in 1891. Three years at prep school were his only formal pre-collegiate education. He graduated from Vanderbilt in 1900, took his M.A. at Columbia in 1901, was married, and spent the following year in Europe. Thereafter he was part-time editor of The Far East, and a freelance contributor to The Outlook, Independent,Review of Reviews, and other vigorous periodicals of the muckraking era. Between whiles, he put in two of the necessary three years of work for a Ph.D. at Columbia, but relinquished the project for reasons chiefly financial. The subject of his doctorate thesis was to have been The Social Philosophy of Swift, a combination of English and Sociology which in those days seemed odd to the pundits.

In 1908, Mr. Lambuth was seized by the quaint fancy of "trying," as he puts it, "to run a dairy ranch in the San Joaquin valley." There he had to cope with such California types as appear in Of Mice and Men. The presence on the ranch of a woman who could have been the prototype of Curly's wife is now remembered by the exranchman as a reason for admiring the veracity of Steinbeck's writing.

After two and a half years of cow care, Mr. Lambuth received a telegram from his father, who appeared to be organizing some sort of expedition up the Nile into Central Africa. Our hero dashed for London to join up, only to learn upon arrival there that the expedition had fallen through. Broke and at a loose end, he hopped a freighter for Brazil where he at first subsisted by teaching English, and then for two years taught psychology and sociology in Portuguese, enjoying it immensely.

Such a globe-trotting background of miscellaneous endeavors should elucidate any tendency the present professor shows to depart a bit from the normal ways of behavior in a New England college town. It explains why in summer time he looks more like a Brazilian planter or a California rancher than a college teacher; and it excellently accounts for his insistence upon regarding literature primarily as an inspired expression of the underlying truths of current living. When he came to Dartmouth from Brazil in 1913, he brought a perspective rare in those of his calling, who too often proceed promptly through graduate school into some safe curriculum niche without any encounters with the hurly-burly of the larger world.

INNOVATOR IN ESSAY WRITING

It occurs to me now that Professor Lambuth's insistence upon a refreshing originality in dress and manner may have been an unconscious method of guaranteeing for himself the continuation of a detached point of view. Perhaps this has been his triumphant defense against falling into the pedagogical pattern. Anyhow, it is my own belief that those who regard his ivory motor car as an appurtenance of the ivory tower are turning the truth precisely inside out.

As a matter of fact, Professor Lambuth's first notable academic exploit was his defeat of the academic essay as the right pattern for undergraduate creative work. To the horror of some colleagues, he invoked the experience of his own freelancing days and insisted that the aim of writing courses in a college should be work publishable in popular current magazines. Within two years after he made his point, such courses at Dartmouth all had increased their enrollment five or ten fold, and they have maintained that level of undergraduate interest ever since.

When I referred to Grandfather Kelley's capture of the gunboats as typical of Grandson Lambuth's teaching, I meant to imply something more than a method of indirection. Those gunboats were not battered into submission by ordnance ashore or in other vessels. They surrendered to a startling idea; and it is an idea startling to students that underlies the success of Professor Lambuth's teaching. He believes (I quote him) that "the whole of education is self-expression, with that analysis and logical thought necessary to it." He does not haul up the heavy guns of rote fact to shoot patterns into the student's memory. Instead, he gallops around the customary undergraduate defenses, outflanks his man, and startles him into the discovery that the acquisition of method and knowledge is a great adventure of the human mind.

Again to quote him, Professor Lambuth holds that "art is an experimentation in the imagination, with the elements of experience, for the purpose of discovering values and meanings, or of inventing them." The word "experience" is the vital part of that statement. He considers it his first task as a teacher of the art of letters to find out what each student's experience has been, and what, as a consequence, he would like to know, do, and be. That is why he has been so strong a proponent of the Honors system, which has increased the intimacy of mental contact between teacher and student.

Near the end of our talk, I asked him what he would like to do to the educational system now in effect, if he were God or President. He said that the surprising accuracy of the Psychological Aptitude Test, and the results of the English 1A sections of apparently exceptional freshmen, have encouraged him to believe that the wisest change would be in the direction of a twoyear course with a perfunctory degree for average men not interested in skilled professions, and more work of a "project" nature for the minority of A and B students who would really benefit from closer personal contact with their teachers.

Last year, for example, he discovered that two of his men liked to see plays, and tried to write them. A little probing con- vinced him that their interest was genuine and that they deserved a "project." After that, the usual honors requirements were modified by common consent. Those two men got at the "values and meanings" of the life of today by studying the current drama on Broadway, plays with subjects of sufficient contemporary interest to rake in the money of playgoers. After seeing TheBoys from Syracuse, they shuttled back to Shakspere and the Greek drama to check up on the origins of its ideas and its technic. There were similar references in the case of each other play. Professor Lambuth acted as a friendly, knowledg able guide. He suggested possibilities; but the students picked their own reading, old and new, without any "musts."

At the end of the year they had sampled human life and history, as caught on the stage with a truth approved by contempo- rary audiences, all the way from AEschylus to Clifford Odets. They were educating themselves, conducting "experimentation in the imagination, with the elements of experience," and Professor Lambuth is not in the least worried over the fact that they may have missed Chaucer, Malory, and Milton.

Telling me about this, he pointed to a bookshelf and said, "Those are the modern plays alone I had to buy to keep up with them."

I counted thirty-four books on the shelf, and I knew why Professor Lambuth, at sixty, has one of the most exciting and up-to-date minds on the faculty. Instead of pounding out the same old stuff, year after year, making undergraduates conform to his notions, he refreshes himself constantly with what interests youth, in the real world.

That, to my way of assessing it, is true teaching. It is so easy, in the academic life, to repeat the same essential lecture year after year, with a few modifications for conscience's sake. David Lambuth takes a harder way, but one more rewarding for all concerned. Last year he had two specific compensations, among others: two lectures which his two drama specialists wrote, to be delivered by him on their subjects.

"I lightened them up a little here and there, for delivery," he told me. "But as a matter of fact, I could have used them verbatim. They were good stuff."

And what more could a teacher possibly ask, in justification of his method, than to produce in less than a year two students who could write his lectures for him?

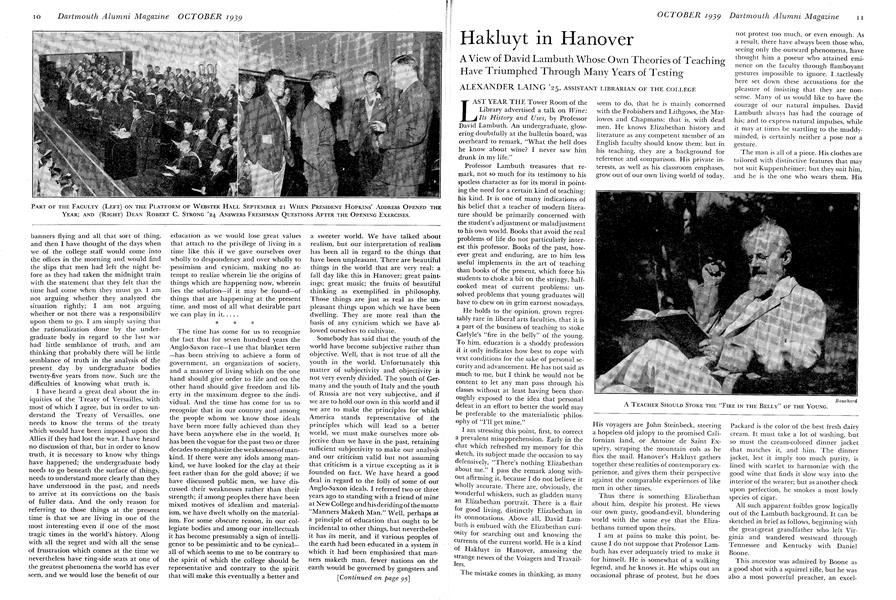

A TEACHER SHOULD STOKE THE "FIRE IN THE BELLY" OF THE YOUNG.

THIS IS THE FIRST of a series ofbiographical sketches to be published monthly during the year, describing the lives of members of thefaculty now at the height of theircareers and influence in the College.

ASSISTANT LIBRARIAN OF THE COLLEGE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThis Too Will Pass

October 1939 -

Article

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

October 1939 By The Editor -

Article

ArticleFriends of France

October 1939 -

Article

ArticleIn Memoriam: W. B. D. H.

October 1939 By FRANKLIN McDUFFEE '21, Anton A. Raven -

Class Notes

Class Notes1912*

October 1939 By CONRAD E. SNOW -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929*

October 1939 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES

ALEXANDER LAING '25

-

Books

BooksREADING THE SPIRIT

January 1937 By Alexander Laing '25 -

Books

BooksHORTON HATCHES THE EGG

December 1940 By Alexander Laing '25 -

Books

BooksUNDERCLIFF. Poems 1946-1953.

May 1954 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Article

ArticleCOLLECTED VERSE PLAYS.

JANUARY 1963 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Article

ArticleBelinda

MARCH 1963 By ALEXANDER LAING '25 -

Books

BooksNOTES FROM A BOTTLE FOUND ON THE BEACH AT CARMEL.

APRIL 1964 By ALEXANDER LAING '25

Article

-

Article

ArticleGuernsey Moore Lectures

May 1934 -

Article

ArticleA Wah Hoo Wah!

April 1954 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Articles

June 1961 -

Article

ArticleThe Father of Dartmouth Football

November 1933 By J. P. Houston '84 -

Article

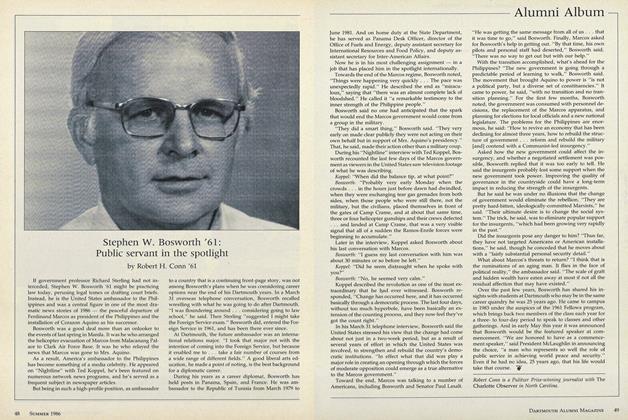

ArticleStephen W. Bosworth '61: Public servant in the spotlight

JUNE • 1986 By Robert H. Conn '61 -

Article

ArticleFREE HEALTH SERVICE

April 1937 By William B. Rotch ’37