After five years as Dartmouth's president, J anted O. Freedman appeary to be...

At commencement last spring, James O. Freedman addressed the first class to have both matriculated and graduated during his tenure. Like the class of '91, Freedman had grown more comfortable and had become more accepted by the community in those four years. In fact, somewhere during that time, Dartmouth's new president had simply become, simply, Dartmouth's president. Among both his supporters and detractors, debate over whether or not he should be president had given way to the realization that he is president, that the man is firmly in charge. He had defined his agenda, and people had grown used to his messages of greater academic rigor and diversity. The first two years had been rocky for both the president and his college. But now, the comfort level was measurably higher.

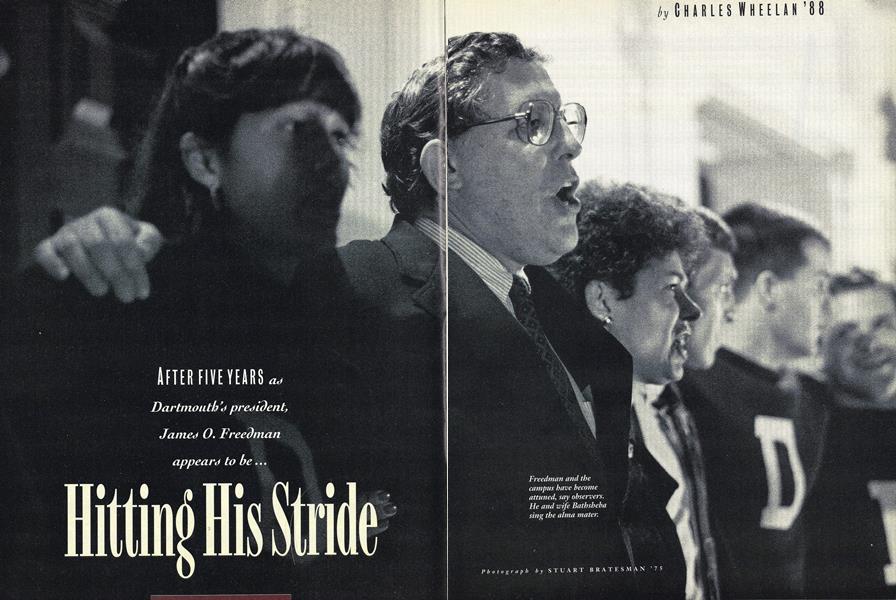

The College appears more at peace with itself than at any point since John Kemeny was president. With his administrative appointments in place, the Harvard presidency filled, and a confrontation with The Dartmouth Review behind him, Freedman seems to have hit his stride. He has gained strong support from the faculty, increasing acceptance by alumni, and the grudging respect of students. This spring, he will have been at Dartmouth five years—the current average tenure for an American college presidentand seems happy to remain for some time to come. Though the changes he has made are not radical, the effects of his presidency promise to be far-reaching. Now that Freedman has truly settled in, this is a good time for an assessment.

As a leader, Jim Freedman is a pragmatist and a consensus builder who has never lost sight of the goals he stated at the outset of his tenure. He made those goals clear in a series of on-campus speeches: to make the campus more intellectual, diverse, and international; and to "heal the warring factions," as he put it to the Boston Globe. In large part, he seems to have been successful. Even his detractors say the man is able. His goals, rather than Freedman's ability to achieve them, were the point of contention from the start.

Freedman came to Dartmouth having committed two youthful indiscretions, in the eyes of some alumni: first, he did not study in Hanover. Even worse, he went to Harvard instead. He did not conform to the stereotype of a Dartmouth grad, nor did his vision for the College coincide with that of the more tradition-minded in the Dartmouth community. The most common fear at the time of his appointment was that Freedman's plans would forfeit Dartmouth's niche as a premier undergraduate institution without ever achieving parity with Harvard, Stanford, and the large research universities. An alumnus from the class of '73 spoke for many when he said, "Dartmouth should aim to be a large Williams, not a small Harvard." Some wondered: as an outsider, would Freedman understand the institutions that make Dartmouth unique? Would a renewed emphasis on research and graduate programs jeopardize the emphasis on undergraduate education? Would the intellectuals and "daring dreamers" so aggressively recruited by Freedman cause the student body to abandon its traditional athleticism and love of the outdoors?

For all the rhetoric, the student body has not disppeared into the library, and Dartmouth has not turned into a large research university. There are more academic achievers on campus, and athletes are included among them. Dartmouth proved dramatically last fall that it still has a viable football program—one that captured an Ivy League championship. A major planning effort has put a firm cap on growth over the next decade.

And then there is Freedman himself. He is no longer the Harvardian outsider. Last November, while helping to kick off a $425 million capital-fund drive, the president showed he had learned how to "talk Dartmouth" while explaining his goals for the place. Speaking in New York's Lincoln Center, he said that his understanding of the College had deepened over the years. Four years ago, in an early speech to the faculty, he had called the place a university a term that is technically accurate but thoroughly incorrect politically. Now he took care before an audience of a thousand alumni to refer to Dartmouth as a college. "I have come to know and appreciate what most of you already knew—the heart of Dartmouth," he said. "I have felt the joy that imbues this special place." He even chose to quote that patron saint of traditionalism, President Ernest Martin Hopkins '01: "Those who miss the joy miss all."

His language reflects a recognition that he can't impose a new culture on the institution. While Freedman certainly has shaped its tone and made a series of key administrative and faculty appointments, he notes: "Cultures, even if one were out to change them, are very hard for individuals to change. Even within the industrial literature—the corporate literature—those who believe a CEO can change the culture believe it's at the margins and slowly and only in degree. I think a college president can change the culture a little bit if people are ready for the change, if what he advocates and urges gains acceptance in the community, and if he is persuasive."

Freedman's management style reflects his philosophy of trickle-down leadership. He likes to state an opinion and let his supporters "bubble to the surface," as he once told this magazine. He is rarely confrontational in private, nor does he usually act alone. Like his favorite Supreme Court decisions, he wants to lead without straying too far in front of popular opinion. Freedman explains, "You have to appreciate that you don't own the place, that you are a shepherd of the place and you are a leader of the place, but that you have to have support for the things you want to achieve."

Freedman's top priority—and the top priority of the Trustees who appointed him—has been to strengthen the academic and intellectual vitality of the institution, both by shaping the curriculum and by attracting more intellectually gifted students. Freedman has clearly left his imprint on the admissions process, both indirectly through his vision for the College and directly through his appointment of Karl Furstenburg, a former Wesleyan administrator, as director of admissions. Furstenberg says that Dartmouth's most important criterion in evaluating applicants is academic achievement, as it has always been. In addition, however, the admissions process seeks to sort out intellectual qualities such as passion for learning, appreciation of ideas, and other things that Furstenberg' refers to as "intellectual zest." The process also tries to recognize open-mindedness, tolerance, and empathy for others. As a sign that at Dartmouth the educational mission is preeminent, the admissions office has added faculty panels on Saturdays for visiting prospective students.

The admissions statistics bear out this approach in a tangible way. The number of high school valedictorians in the freshman class has gone from 110 in the class of 1993 (out of 1,000) to 168 in the class of 1995, a 53-percent increase. Freedman has made it a goal to seek out more valedictorians, Westinghouse Science winners, National Merit Scholars, and other academic stars. Professors and students differ on whether or not changes are evident in the student body. "I have some extraordinary freshmen and sophomores whom I would not have found when I arrived," says Pamela Crossley, professor of Chinese history. Yet she has not observed a change in the profile of the student body overall.

Hugo Restall '92, editor of The Dartmouth Review, argues that the College was already an intellectual place before Freedman arrived, and History Professor Jere Daniell '55 would agree. The institution's anti-intellectual reputation, Daniell says, is based on a past image of Dartmouth that is not very accurate. He did a study of his own Dartmouth class and found that the percentage of persons who went on to get Ph.Ds was only a percentage point or two below the comparable class at Harvard.

Nonetheless, the Presidential Scholars Program, one of Freedman's first attempts to attract intellectuals to the campus, clashed with mainstream opinion when it was first implemented. The premise of the program was that high school academic stars designated as Presidential Scholars would be flown to visit the campus, much as athletes are traditionally recruited. The point of contention was that once matriculated, Presidential Scholars would'be afforded special academic privileges. Many students found it inappropriate to create an academic elite at an Ivy League campus.

The program has been greatly modified over the past few years. High school academic stars are still recruited and flown to campus, but Presidential Scholars are not selected until junior year—based on their performance at Dartmouth. Chosen Scholars are invited to do research one-on-one with a member of the faculty. The program is now extremely popular with students, who talk up the research opportunities and avoid using the detested term "Presidential Scholar." Ninety out of the 1,000 students in the class of 1993 are currently doing graduate-level research with their professors.

Within the broader goal of bolstering the College's academic mission, Freedman has committed himself to elevating the importance of the sciences and increasing the number of women in the field. The first new building to be completed during his tenure will be a chemistry center, which he considers both a substantive and a symbolic success. Under Freedman a Women in Science Project was created, offering meetings, lectures, and activities for freshman women to encourage them to study science and math as potential careers. Science is expensive, however, and attempts to offer first-rank education are bound to strain resources as they have at other elite schools. David Lindgren, associate dean of the faculty for the social sciences, points out that money spent on equipment for a handful of students in the sciences can support two or three government professors. Moreover, to become a leader in the sciences, Dartmouth will have to increase the quantity and quality of its graduate programs. The division of resources, both between science and the humanities and between graduate and undergraduate programs, is likely to be an ongoing subject of debate.

Freedman has also insisted that Dartmouth expand its international focus beyond the efforts set by John Sloan Dickey '29, the College's first truly international president. Freedman is especially interested in the Pacific Rim; the College has added a foreign-study program and the Tuck School now operates in Japan. Japanese was added to the curriculum, and last May Freedman made a ten-day trip to Japan to build economic ties, pursue further educational exchanges, and address some 75 Dartmouth alumni. The curriculum has been expanded in other directions as well. Arabic and Hebrew are now taught, and foreign-study programs have been added in Italy, Mexico, and Brazil.

One exception to Freedman's hands-off style is recruitment of faculty. He has been active in bringing in at least eight scholars of international distinction, including former Geographer of the United States George Demko, now head of the Rockefeller Center; Robin Yates, former Harvard scholar and now the Burlington Northern Professor of Asian Studies; and former New York University star Dale Eickelman '64, who now holds the Ralph and Richard Lazarus Chair of Anthropology and Social Relations. The capital campaign is expected to create endowments for another 30 chairs over the next five years.

Freedman is clearly popular with the professors. His involvement in the recruitment of faculty, his academic background, his dedication to the intellectual life of the College, and his strong stand on the Review have given the faculty a moral shot in the arm. Freedman jokes that the two major issues at faculty meetings these days have been parking and medical benefits. "There has not been a lot of discontent on the academic side," he says. "I think it reflects a kind of inner confidence on the faculty's part that we're doing well in faculty appointments, we're doing well in tenured appointments. The faculty is gratified, pleased, contented with the fact that we're on the right course academically and that we're able to attract the people we want to attract."

The alumni body has been a harder sell than the faculty. Freedman pauses before assessing the relationship. "I think when I came there was a good deal of feeling that I was an outsider, that I was new to Dartmouth. I used my first several years to state my ambitions and visions for Dartmouth. It takes alumni at any institution a little while to get used to a new president. I've been struck this alumni season how different the temper is, how much warmer and supportive My sense is the alumni have become very supportive and by and large share my goals for Dartmouth."

Based on conversations with alumni, Freedman seems correct on both counts. The relationship has indeed improved steadily. Still, graduates often speak of the man as "distant." Although he speaks to some 15 alumni clubs a year and has instituted a State of the College Address, most alumni contacted for this article still find him impersonal and somewhat enigmatic. "Alums like his philosophies, they like him, but they are not particularly excited," comments a member of the Alumni Council. On a one-to-one basis, Freedman is affable and warm, revealing a quiet sense of humor. He brightens up at talk about international affairs, or higher-education issues, or—best of all-books. In a small, informal gathering, on the other hand, the president can seem stilted. He does not exude the personality and charisma many alums have come to associate with Dartmouth presidents. Fundamentally a private person, he clearly dislikes making small talk.

Freedman is no Mr. Chips to students, either. Although he seems genuinely to enjoy contact with them, he clearly prefers a formal environment. Students who have something to say to him will find him more accessible than presidents past; he has set aside weekly office hours for student visits, and he meets frequently with dormitories and honor societies. But the contact they crave is informal—President Dickey walking his dog across campus, say, or John Kemeny explaining a formula. Comments former Student Assembly President Brian Ellner '92, "We expect our president to be out on the Green playing Frisbee. That just isn't the case anywhere." Freedman is often described as the invisible president; "Freedman sightings" are a topic of conversation.

Perhaps no incident encapsulates this image of distance better than Class Day 1991. As the day progressed toward the ritual breaking of the clay pipes, Freedman was seated on stage with other guests of honor. Near the end of the program, the class speaker took the rostrum. He thanked his classmates and turned to thank the president. The seat was empty. Freedman's aides say it was one of the busiest days of the year for the president, and that he had left early to speak at the 50th reunion luncheon. The laughter from the crowd reflected more than the speaker's surprise; it reflected Freedman's somewhat mysterious ways. To the assembled students, the departure was another example that Freedman's priorities often lay elsewhere. In fairness to the president, and perhaps to put the discontent in perspective, the most recent U.S. News & World Report survey of American colleges and universities ranked Dartmouth number-one in student satisfaction.

The Fact that Freedman can say he is comfortable with the place, and can feel the support of most of his constituents, seems remarkable in light of his first two years here. He had barely settled in before The Dartmouth Review published a front-page cartoon portraying him as Hitler. The editors entitled the cover story, "Ein Reich, Ein Volk, Ein Freedmann." "Can you imagine being the new head of a college, and being a Jew, and having an alumni-supported publication showing you as a Nazi?" says an administrator who works closely with the president. "How comfortable would you feel with the place?"

When, in the fall of 1990, staffers on the paper inserted a passage from Hitler's Mein Kampf on the masthead, Freedman struck back. Invited by students to speak to a rally against hate, he gave a fiery address that accused the paper of racism, sexism, homophobia, and anti-semitism. The Review and its supporters, unaccustomed to being called on their own rhetoric, cried foul, saying that Freedman had judged the paper before all the facts were in. (The editors claim that the Hitler quote was planted by disgruntled staffers.) William Modahl '60, chairman of the New York-based Hopkins Institute of conservative alumni, accuses Freedman of using a bogus incident to "stir up animosity against people of opposing views."

On campus, however, the Review incident seemed cathartic. "There has certainly been a welling up of support and a coming together of the campus," Freedman says of the incident. Indeed, response by both students and faculty was overwhelmingly positive; the Review, on the other hand, now seems largely ignored by students.

The far right did more than attack the new president personally. It also came down hard on the "universitification" of Dartmouth. Fears about the College becoming a large university were fueled by a long-term campus plan prepared by the Philadelphia-based architectural consulting firm Venturi Scott Brown. When it was released that the College gave the firm the number 10,000 as the student body's maximum conceivable size, some interpreted this as a blueprint for expansion. The College denied any intention of growing to that size. Alex Huppe, director of the Dartmouth News Service, compares the architectural plans to the load limit of a bridge. He explains, "If you want to build a bridge for 50 cars, you tell the engineer to make it safe for 400. Why? Because you don't ever want to approach its limit." Nonetheless, The Dartmouth Review continued to claim a vast planned expansion.

Much of the speculation about the direction of the College should have been put to rest by the Planning and Steering Committee Report, an 18-month study commissioned by Freedman and chaired by Provost Strohbehn. The committee of 35 faculty, students, administrators, and the president of the Alumni Council was charged with articulating "a vision of the College which will guide us for the next ten to 15 years." Among many other conclusions—which were accepted by Freedman and the Board of Trustees the report stated explicitly: "Over the next five years, Dartmouth should maintain its undergraduate enrollment at its present size of approximately 4,200 students. For the long run, the Board of Trustees should set an upper limit of 4,300 students. This limit is important because for Dartmouth to maintain a learning environment of close contact between students and faculty, it must remain relatively small in size." The same report reiterated a 1966 decision by the faculty of Arts and Sciences that graduates not exceed ten percent of undergraduate enrollment.

The report laid before the president and Board of Trustees what many considered selfevident. "Dartmouth is so overwhelmingly undergraduate by its ambience," says Jere Daniell. "Dartmouth will never become a graduate institution. It doesn't have the faculty it doesn't have the money, and it doesn't have the inclination."

The entire planning document, in fact, keys off this idea of size. The plan's central tenet is the idea of maintaining "pinnacles of excellence" of concentrating resources toward areas that Dartmouth is capable of doing best. Rather than attempt to be a true university—a universal institution that covers all academic bases the College has chosen to vie for international stature in select fields: medical practices, say, or language study. The plan calls for faculty to grow somewhat, and for some existing graduate programs to expand. But it is clear that, even in the year 2000, people will be able to refer to Dartmouth as "the College" without stretching credulity.

Diversity is another issue that continues to be raised by the right. But moderates around the nation are also struggling with the issues raised by the nation's rapidly changing demographics, as is evidenced by the fact that Dartmouth's Alumni Council asked the president to speak on the topic at a meeting last spring. (This magazine published an adapted version of the speech in the October issue.) Two of Freedman's avowed goals when he arrived at Dartmouth were to achieve "parity" between men and women and to create a more diverse student body. He has succeeded at both. The class of 1995 reflects an increase in the percentage of women (48), minorities (23), and public high school students (62). Freedman considers diversity imperative to both the educational climate on campus and the College's larger mission of creating an educated society a society of which one third will be members of racial and ethnic minorities by the end of the century. He explained in his Alumni Council speech: "It has long been recognized that, educationally, we simply cannot have a campus made up entirely of people who are very much like each other."

Some alumni question the means more than the ends. Dartmouth considers race, socioeconomic characteristics, and geographic origin as factors to consider for admission—along with activities; board scores grades; class rank; athletic, artistic, or other expertise; and status as legacies. Explains Freedman, "The Dartmouth Trustees have said we would pay special attention to blacks, Native Americans, northcountry poor. We have done that. And I think it's important we reach out. If this were an institution that had five-percent minorities instead of 23-percent minorities, we would be a much poorer educational institution than we are." This recruiting effort does not mean that the College has lowered academic standards to admit inferior students any more than recruitment of athletes creates an inferior student body. Dartmouth has been successful lately in attracting an increasingly diverse applicant pool and in convincing a higher percentage of minority students accepted to attend. "The basic means of achieving diversity is to cast the net for applicants very widely," says Freedman. He points out that last year 3,400 secondary schools were represented among candidates for admission—up 300 from the previous year. "I think that's the fundamental vehicle for achieving diversity," he says.

Peple who have dealt with the president regularly over the past four years say that he seems more visibly relaxed and confident in front of groups of alumni and students. "You do hit your stride at some point, and I'm interested that people report that," Freedman says. He leans forward and smiles broadly when he recounts his friendship with leaders in the arts and academe. During the 1991 Commencement, Aleksander Solzhenitsyn visited campus to receive an honorary degree. Freedman, an avid collector of books, shows his delight at having signed copies of the author's work. "One of the great privileges is the people you have an opportunity to meet," he says of the presidency. "To have at your dinner table Saul Bellow or Carlos Fuentes and the list can go on is a rare privilege."

At the same time, Freedman has earned a national reputation as a leader in higher education and has been able to use his position as a podium to speak out on national education issues. His op/ed pieces have appeared in The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, the Boston Globe, the Atlanta Constitution, and the Hartford Courant, and he has many more speaking invitations than he can accept. The president seems least to enjoy his role as fundraiser, which consumes more than a third of his time. But that hasn't precluded success in that realm; the development office continues to break records almost every year.

Freedman is philosophical about changes he considers necessary for the long-term health of the institution. "I try to tell people that Dartmouth is the product of evolution, and that Dartmouth has changed by degrees at many, many stages. Dartmouth would not be an international institution today if it hadn't changed at some point. Dartmouth would not be of the high quality it is today if it hadn't kept pressure on its admission standards all through the period of years. One looks back now at the presidencies of a President Hopkins or a President Dickey and sees very significant changes during their presidencies which left Dartmouth stronger than when they became president," he says.

Most evidence indicates that Freedman has been successful in implementing his agenda and that the agenda itself is finally gaining acceptance. "When we start discussing whether freshman trips should be called 'trips' or 'pea-green trips', or something else, we're discussing little issues," says Burgwell Howard '86, associate director of alumni affairs. "The big issues have been won or are not issues anymore."

At the very least, Freedman has had, in the words of one member of the administration, "a calming influence on the place." The campus is relatively peaceful, both by Dartmouth standards and compared with a system of higher education that is under siege across the country for everything from collusion to political correctness. Time magazine wrote in an article about Donald Kennedy's resignation from Stanford: "These days, perhaps only a masochist can fully enjoy the job of a university president." James O. Freedman is clearly no masochist. Indeed, he has never seemed to enjoy the job more.

Freedman and the campus have become attuned, say observers. He and wife Bathsheba sing the alma mater.

The president hefts the Lambert trophy after the Ivy title game. The win helped calm alumni fears about recruiting.

The Women in Science Project encourages female students to enter the field.

Some alumni contrast Freedman's style with Dickey's outdoorsy image.

Freedman attended Class Day with other dignitaries but took some heat when he left for the 50th reunion.

Some wondered: as an outsider would Freednutn understand the institutions that make Dartmouth unique?

Freed man's top priority has been to strengthen the academic and intellectual vitality of the institution.

He does not exude the personality and char Luna many alums have come to associate with Dartmouth presidents.

Freednan joked that the two major issues at faculty meetingd have been parking and medical benefits.

The College seems more at peace with itself than at any point since John Kemeny was president.

Charles Wheelan is a graduate student at Princeton's Woodrow Wilson School. His last story for this magazine, on Paid Tsongas '62, appeared in the October issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Gentleman's B-Plus

February 1992 By Eric Konigsberg '91 -

Feature

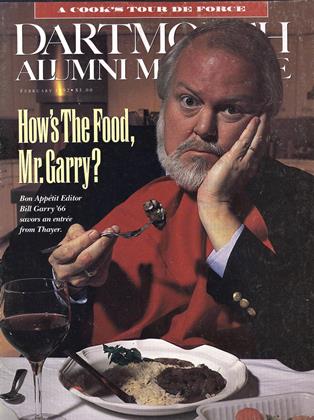

FeatureEat Here

February 1992 By CHRIS WALKER '92 and TIG TILLINGHAST '93 -

Feature

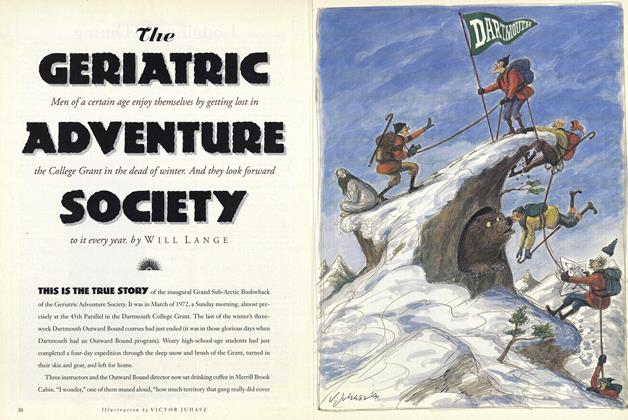

FeatureThe Geriatric Adventure Society

February 1992 By Will Lange -

Article

ArticleA Nation of Gentlemen

February 1992 By Professor Jeffrey Hart -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

February 1992 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleThe Trophy Finally Stays Put

February 1992 By Robert Sullivan '75

Features

-

Feature

FeatureLewis Dayton Stilwell (1891-1963)

MAY 1963 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"A Very Laid-Back Place"

Mar/Apr 2009 -

Feature

FeatureA Quiet Revolution

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1983 By David Shribman -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

Mar/Apr 2012 By Jay Mead '82 -

Feature

Feature"Little Joe" Wentworth, 1900: Scholar, Athlete, Gentleman

OCTOBER 1984 By John F. Anderson '34 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 By JOHN SHERMAN