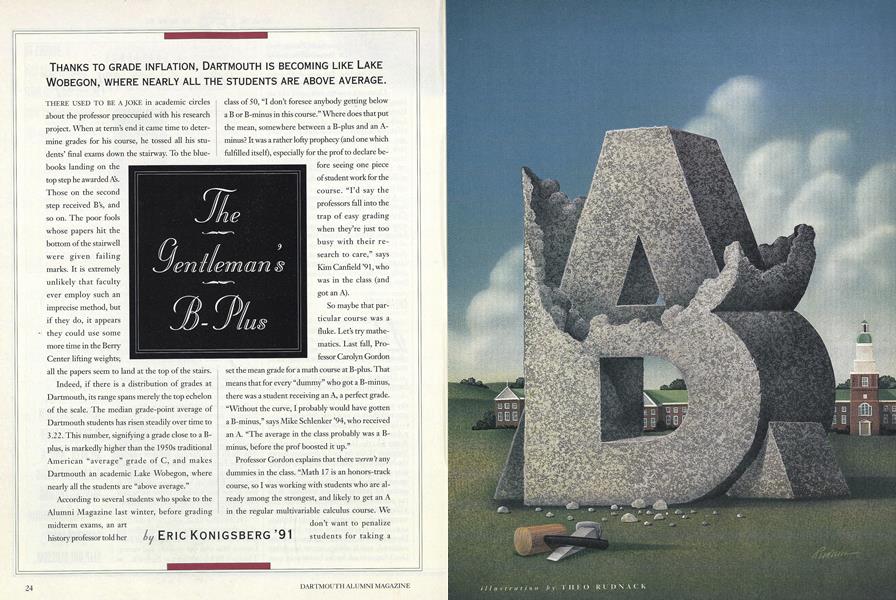

Thanks to grade inflation, Dartmouth is becoming like Lake Wobegon, where nearly all the students are above average.

THERE USED TO BE A JOKE in academic circles about the professor preoccupied with his research project. When at term's end it came time to determine grades for his course, he tossed all his students' final exams down the stairway. To the bluebooks landing on the top step he awarded As. Those on the second step received B's, and so on. The poor fools whose papers hit the bottom of the stairwell were given failing marks. It is extremely unlikely that faculty ever employ such an imprecise method, but if they do, it appears they could use some more time in the Berry Center lifting weights; all the papers seem to land at the top of the stairs.

Indeed, if there is a distribution of grades at Dartmouth, its range spans merely the top echelon of the scale. The median grade-point average of Dartmouth students has risen steadily over time to 3.22. This number, signifying a grade close to a Bplus, is markedly higher than the 1950s traditional American "average" grade of C, and makes Dartmouth an academic Lake Wobegon, where nearly all the students are "above average."

According to several students who spoke to the Alumni Magazine last winter, before grading midterm exams, an art history professor told her class of 50, "I don't foresee anybody getting below a B or B-minus in this course." Where does that put the mean, somewhere between a B-plus and an Aminus? It was a rather lofty prophecy (and one which fulfilled itself), especially for the prof to declare before seeing one piece of student work for the course. "I'd say the professors fall into the trap of easy grading when they're just too busy with their research to care," says Kim Canfield '91, who was in the class (and got an A).

So maybe that particular course was a fluke. Let's try mathematics. Last fall, Professor Carolyn Gordon set the mean grade for a math course at B-plus. That means that for every "dummy" who got a B-minus, there was a student receiving an A, a perfect grade. "Without the curve, I probably would have gotten a B-minus," says Mike Schlenker '94, who received an A. "The average in the class probably was a Bminus, before the prof boosted it up."

Professor Gordon explains that there weren't any dummies in the class. "Math 17 is an honors-track course, so I was working with students who are already among the strongest, and likely to get an A in the regular multivariable calculus course. We don't want to penalize students for taking a more difficult course. I felt that a course with a mean set at B-plus was appropriate." Gordon readily accepts that a B is a respectable grade: "I mean, even students below the mean, the ones I gave B's and B-minuses, were doing really good work."

These two examples show some or the pressures pushing up grades busy professors and the attitude that Dartmouth students are already above average. But grade inflation itself began a long time ago, following World War 11. In the days when a Dartmouth degree was enough to land a job, one's transcript didn't matter much. Then came the G.I. Bill. Throngs of young men who had served in the army returned from the war and enrolled at universities. Older than their non-vet classmates, and many of them with wives, these men were among the first to recognize the link between their college education and their future, and they tooled accordingly. And even before this was to happen, in the 19205, the endowments of the Ivies and other top schools began to afford each college the opportunity of educating a more geographically and socioeconomically diverse student body. Dartmouth, in fact, was the first college in the nation to institute selective admissions, in 1924, and thus began to matriculate better students, an increasing number of them from public high schools. The more talented, harder-working students began to raise the average GPAs at competitive colleges.

Gradually, the difficulties colleges laid before the students changed. In the old days, a student who had prepared himself properly for college had little trouble getting in. Flunking out, on the other hand, wasn't so difficult. Beginning in the thirties but accelerating after World War Two, elite colleges became harder to get into. At the same time, it was easier to graduate. Today, a student has to give up on his courses entirely in order to flunk out. These factors help explain why the average amount of time a student spent studying declined from 5.2 hours a day in 1958 to 3.3 a day in 1986. And, as studying declined, the average GPA went up, from the equivalent of 1.6 in the 1910s, to 2.48 in 1949-50, to 3.1 in the seventies, to 3.22 in 1989.

A big push came in the late sixties, when grades themselves came under fire. "It's not accidental," says History Professor Jere Daniell '55 of the era's grade inflation. "With the anti-Vietnam movement came a general attack on the establishment, an attack on the idea of hierarchy. Grades create a hierarchy between the professor and the student."

Some faculty at the time also felt an obligation to help students avoid the low grades that would make them vulnerable to the Selective Service. "There was pressure on the faculty from students to help them maintain an above-average average," says Ted Mitchell, professor of education. It ratcheted grades up in the late sixties. The draft went out in 1972, but grades haven't come down."

The Kemeny era introduced new forces behind rising grades. The first was the Non-Recording Option, which allows students to decide whether to keep a grade in a class or record it simply as passed or failed. Students can take the option with up to three classes. The idea is to encourage students to study subjects they might be afraid to take otherwise.

Then there was the Dartmouth Plan. The College decreased its courseload to three classes a term from four or five, and cut two weeks off each academic term, in the move from semesters to year-round quarters. While coursework was thus intended to be more concentrated, many syllabi were shortened to accommodate the shorter terms.

With the D-Plan came off-campus study. Language Study Abroad programs are known GPA boosters. Easy schedules and foreign teachers contribute to the relaxed grading.

Then came the eighties, the era of grade grubbing. "Students are more grade-conscious than ever," says Dean of Upperclass Students Dan Nelson '75. "I have students coming into my office challenging the difference between a B-plus and an A-minus. That sort of distinction used not to matter."

With scholarships available and firm financial status no longer requisite for a Dartmouth degree, a graduate degree came to be more of a requirement for success. As Dartmouth was growing more selective, so were graduate schools, and the cutthroat was born. "I see a real tension between the credentialling function of teaching college and the educational function," says English Professor Jeffrey Hart '51, who himself is not known for particularly stringent grading. "What I'm trying to do is teach Johnson and Burke and not worry about a student's future, but there's been a change in the attitude of students, more and more of whom are going to graduate schools. In the 19305, a C from Dartmouth didn't matter much if you wanted to go into business. Today it can."

Alas, graduate schools have caught on to the inflated undergraduate marking system at Dartmouth and around the country. "A B-plus carries less weight than it used to," says Tuck's Director of Admissions Sam Lundquist. "I'd say [grade inflation] is generally no more of a problem at Dartmouth than at the other top schools. I think if you called any of my peers, they'd say the same thing. We look at class rank."

Another factor: competition among departments to attract students. "I have heard anxious faculty speculate that if you have a reputation as a particularly hard department, you might have a difficult time attracting majors," Nelson says.

Well, perhaps we can say that grades don't really matter in the end anyway. Many of the pre-law types followed similarly challenging (or unchallenging) courses of study, and most of the pre-meds have had to take the same tough prerequisites. But what about competition for jobs? Not everyone going through corporate recruiting was a history major, right? Try explaining that to your interviewer from Goldman, Sachs.

"These people at interviews ask me: 'So what's your GPA?' and I'm thinking 'No no no no no! You don't understand Sam Kingsland '91, a geology major who studied more than 20 hours a week, said in an interview before graduation. "I've been taking hard classes. I'm a rocks major. You've got these English majors with their 3.5s, and the science majors will all have 3.0s and be working twice as hard."

Which brings us to the most important question: except for the small matter of jobhunting, does grade inflation matter? Is it a sign that Dartmouth is slipping intellectually?

"Students at the College today are better than they have ever been," replies Daniell. "I have some of the papers from when I was an undergraduate, and I would give those papers a significantly lower grade than they got. The grading standard has changed, but grade inflation reflects absolutely no deterioration of Dartmouth's standards or its quality of education." Dean of the Faculty James Wright agrees, saying, "Students continue to beat the averages" the faculty sets for them.

True, most of my classmates were A students in high school, so they expect to continue to earn top marks in college. In line with this theory, the average GPA for seniors at Princeton, a comparable school for super-achievers, was a 3.31 for the 1990-91 academic year. At the University of Virginia, a first-rate school with somewhat lower admissions standards, the average GPA falls at 3.0. Denison's average is 2.9. University of Hartford: 2.55.

Film Studies Professor LaValley insists that Dartmouth students are better than those he taught at the University of California at Berkeley, Rutgers, and USC. "I gave a lot more Cs at those schools. I kept saying the level of work from students is the same from school to school, but it isn't. At those schools, there are many more students who don't write very well."

At any rate, Dartmouth professors seem like tough graders compared to some of our competition. Brown and Stanford have grading systems that allow students to take any and every course pass/fail, if they so desire. In addition, a failed course is automatically dropped from the transcript. Brown even has a credit requirement of 30 courses (compared with Dartmouth's 35) so that a student can fail about five classes, not have them affect the GPA, and still graduate on time. And, Brown has no pluses or minuses on its grading scale, meaning that a B-plus student is likely to receive a flat A from a sympathetic professor. And, Brown has no D's, making a C ("not a common grade here," according to Brown Registrar Katherine Hall) the lowest grade one can receive. A student can even manipulate his transcript by flunking a course in which he is about to get a C, and thus get it erased from his record. "Students have ally failed classes rather than get a C," says Hall, "but only rarely. There's a story of how once a professor refused to fail a student who had tried to do so." Nice to see them upholding standards.

So at least we know that grade inflation is a nationwide phenomenon. Dartmouth's Dean of Admissions and Financial Aid Al Quirk '49 says he sees it even in the secondary schools. What does it matter? "I don't think it's a problem, because grades don't measure anything anyway," says Ted Mitchell. He describes two hypothetical classroom scenarios in which all the students in the course receive As. One is an upperlevel seminar taught by the "toughest prof in the history of the College... She makes tremendous demands on her students; they have to read and analyze a book for each meeting. At the end of the course, every student is required to submit an article of original research to a publication. They all do it, because of the demanding routine of the course, and they all earn their As." Mitchell's alternative example involves "Professor Bozo," whose chief priority is his research. "He doesn't give a tinker's damn about the course. The only requirement for the course is that each student submit one paper at the end of the term." Just before the end of the term, he goes to New Zealand, and in a hurry to turn his grades in, Professor Bozo slaps A's on all the papers.

"We have no way of making judgments between the two hypotheses based solely on the grades from those classes," Mitchell concurs. "I can't say that grading is getting easier, because higher grades could mean harder courses, or it could mean the students are learning better. That's the reason why I don't believe in grading on a curve."

Ah, the curve: that scientific instrument to ensure that grades are evenly distributed among the students in a given course. The problem is, only professors in (you guessed it) the science departments are apt to use a curve. It is intended to scale grades up, so that a particularly difficult test is graded relative to students' performance on it. For the sciences, this means that the average grade is generally set at a B minus. And it is here where the debate over grading standards heats up. "It's difficult for a science major to explain to his roommate, who is working half as hard as he is but taking humanities courses and getting A's, why he himself is getting B's," says Chemistry Professor Russell Hughes, speaking of the widening gulf between average grades in the three academic divisions.

"People say that science professors can set exams where you get a wonderful distribution of grades. I agree. With so many parts to an exam, you can assign points and compute an exact score. Now, if you say that you can only put a paper in three or four categories, 'excellent,' 'very good,' 'good,' and so on, I don't see why [humanities and social science faculty] only use the top four grades. Why should a paper that's only 'good' get a B-plus?"

Hughes, who considers a B-plus a "damn good grade," insists that the odds are that "a student majoring in economics will probably get lower grades than someone majoring in French. Simply by majoring in the humanities, the odds are that a student will have higher grades than a science major."

"Grades don't tell us how well a student does in a class unless we know what the mean is," says Hughes. "The system we have now is downright unfair." So Hughes has submitted a proposal to the faculty's executive committee. The proposal requires that a student's grade in each course be divided by the average grade given in the course. Discussion is still at the initial stage on Hughes's proposal, according to Wright, who would not speculate on the feasibility of its being approved.

Professors in the humanities are not so keen on the idea. "Allocating grades is an abomination," says French and Italian Professor John Rassias. "To say that we have to give out two A's, two B's, and so on is absurd. I'm saying you measure the kid individually against himself or herself instead of some idiot curve. I want my students to do well, everyone should. Wanting to be known as a tough teacher is ridiculous. Tough isn't in the grading, it's in what you ask of the students in the work involved." Rassias says he would give all his students A's if he felt they all deserved them. Students are quick to point out the motivating factor of getting good grades. "A bad grade is frustrating," says one recent Phi Bete premed (who, incidentally, claims she studies only five hours a week). "I'm more excited to do extra work when I know I'm going to get an A in a course."

Professor Donald Pease of the English department is perhaps more accepting of the curve concept than Rassias, yet no more interested in employing it. "Most humanists wouldn't even know what to do with a bell curve if we saw it," he says. "The fundamental difference is that the sciences are testing for precise knowledge, whereas in the humanities the emphasis is on the qualitative. You also have, in the humanities, the continuation of what a student has already begun to learn in secondary school, that is, how to write well. With the sciences, the student may well be learning entirely different approaches to die subject to be studied."

Still, every student seems to be cheated by one aspect of grade inflation: it effectively reduces the fourpoint scale to one-and-a-half points, forcing students to compare precise GPAs based on imprecise grades. There are 100 possible GPAs between an A-minus and a B-minus average, but only three grades. There are, then, 33 possible distinctions between a B and a B-plus, yet the distinction between the two is often negligible, even when decided by the same professor for the same course. "I don't have any real confidence in the difference between a B and a B-plus," says Jeffrey Hart. How odd, then, that the magna cum laude graduates of the class of 1991, the top 15 percent (with a minimum GPA of 3.63), should be separated from the cum laudes, the top 3 5 percent (cutoff at 3.43), by only one-fifth of a point. That's 200 students in the class sharing a .2 spread, or ten at every hundredth of a point. Isn't that a waste of a grading scale which ostensibly was designed to range from 60 to 100? M

"A B-PLUS CARRIES LESS WEIGHT THAN IT USED TO." Jack School Admissions Director Sam Lundguist

"SIMPLY BY MAJORING IN THE HUMANITIES, THE ODDS ARE THAT A STUDENT WILL HAVE HIGHER GRADES THAN A SCIENCE MAJOR." Chemistry Protessor Russell Huqhes

"MOST HUMANISTS WOULDN'T EVEN KNOW WHAT TO DO WITH A BELL CURVE IF WE SAW IT." englsih Protessor Donald Pease

Eric Konigsberg is an intern at the Washington Monthly in Washington, D.C.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHitting His Stride

February 1992 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureEat Here

February 1992 By CHRIS WALKER '92 and TIG TILLINGHAST '93 -

Feature

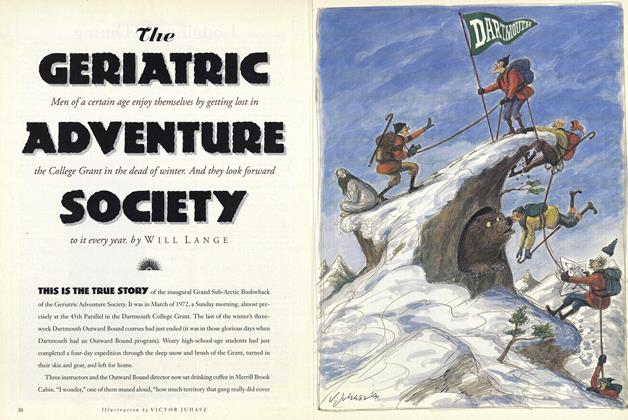

FeatureThe Geriatric Adventure Society

February 1992 By Will Lange -

Article

ArticleA Nation of Gentlemen

February 1992 By Professor Jeffrey Hart -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

February 1992 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleThe Trophy Finally Stays Put

February 1992 By Robert Sullivan '75

Features

-

Feature

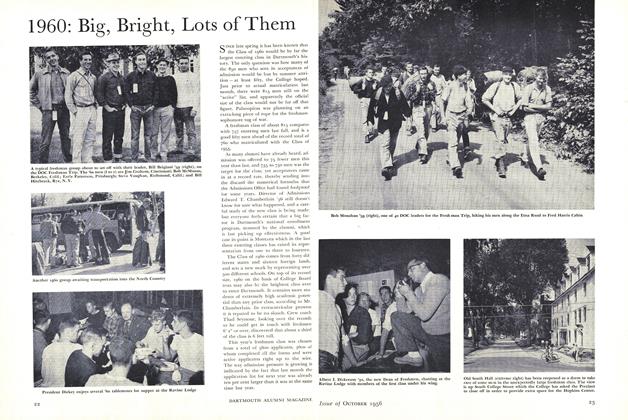

Feature1960: Big, Bright, Lots of Them

October 1956 -

Feature

FeatureToro's President

DECEMBER 1966 -

Feature

FeatureIn Another Country

May 1980 By Beth Ann Baron -

Feature

FeatureNoble Boots

JUNE 1996 By Chris Clarke ’75 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChris Miller '97

OCTOBER 1997 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Feature

FeatureA Thinking Man's TV Journalist

June 1960 By JAMES B. FISHER '54