As the "Me" era comes to an end,students are getting

When Marian Wright Edelman, president of the Children's Defense Fund, stepped to the rostrum to give the 1988 Commencement address, she faced an audience already somewhat disenchanted with the ideals of the eighties. At Dartmouth and across the country, an era of self-absorption was beginning to give way to something kinder and gentler.

Edelman delivered a sharp admonition to the students who, by virtue of background, education, and demographics, were about to join the ranks of the "Me Generation." She warned, "If the only principle our society adheres to is economist Adam Smith's invisible hand, it leaves little or no room for the hand of man, or woman or of God...There is then a hollow- ness left at the core of a society whose members share no mutual goals or joint vision—nothing to believe in except self-aggrandizement."

Her message was not new, of course. The eighties evoke images of Wall Street, the people who work there (Yuppies), and the cars they drive (BMWs). This was the decade when Michael Milken could make $500 million in a single year while Ronald Reagan gently chided the poor for not pulling themselves up by their boot- straps. Even the erstwhile students of the sixties can be comfortable in suburbia, 0 as media images of Woodstock's 20th anniversary showed.

At Dartmouth during this decade, students flocked to investment-banking programs in unprecedented num- bers; education and non-profit work were the big losers. "For a long time, if you wanted to go into social service, people thought you were an absolute fool," explains Faith Dunne, chair of the Education Department. From 1976 to 1986 the number of entering freshmen who considered it important to "be very well off financially" increased from 44 percent to 60 percent while the number who aspired to "develop a meaningful philosophy of life" dropped from 79 percent to 60.

But all generations must come to an end, be it by the stock market crash that terminated the Roaring Twenties, or the waning of the war in Vietnam that eased out the sixties. As this decade draws to a close in Hanover, there are clear indications—a renewed interest in teaching, a decline in corporate recruiting, a nascent awareness of environmental issues among the mainstream—that the Me Decade may slowly be giving way to something more altruistic...

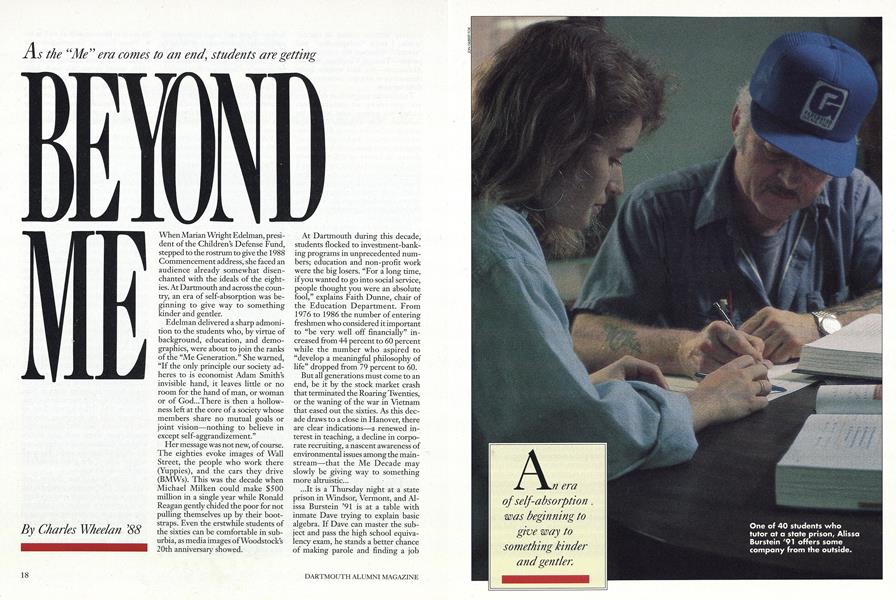

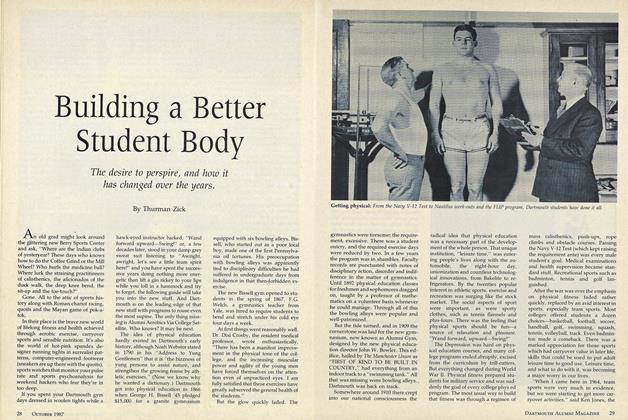

...It is a Thursday night at a state prison in Windsor, Vermont, and Alissa Burstein '91 is at a table with inmate Dave trying to explain basic algebra. If Dave can master the subject and pass the high school equivalency exam, he stands a better chance of making parole and finding a job when he gets out. Burstein, who is one of approximately 40 Dartmouth students who tutor at Windsor and at a prison in nearby Woodstock, explains, "It's not so much the schoolwork but that he has some contact with what is outside the fence. When I come, it's a break in the routine and it gives him something to look forward to."

The prison tutoring program is coordinated by the Tucker Foundation, the driving force behind student voluntarism. Through projects like Big Brother/Big Sister, Adopt a Grandparent, Meals on Wheels, and Literacy Training, Tucker involves a thousand students a year in service activitiesa five-fold increase from 1982. Tucker Fellowships also make it possible for 40 to 50 students a year to spend a term off campus doing some sort of public service. When Susan Conroy '87 went to Calcutta in 1986 to help Mother Teresa, it was funding from Tucker that made the trip possible. Since then, students have taught English to boat people in Hong Kong, implemented a program for wheelchair athletics in Honduras, and counseled drug addicts in Singapore. For the past five years interest had been focused on international problems, according to Jan Tarjan '74, the Tucker Foundation's associate dean, but she says that the trend has slowed and students are now more eager to get America's house in order. When Kevin Hao '89 wanted to assist the homeless and the terminally ill during the summer of 1988, he went to work with AIDS patients in the Bronx.

Is the growing interest in Tucker programs a portent of a new idealism on campus? Dean Susan Wright, who worked closely with the classes of '85 and '88, is convinced it is one sign that more students than ever are determined to "make a difference" while in school and after graduation. "Idealism is the distinguishing characteristic of the class of' 88," she says. "There is a definite orientation toward public service—not just voluntarism, but journalism and teaching as well."

The Tucker Foundation does not keep data on volunteers who go on to service-oriented careers, but among graduating seniors there appears to be a shift away from Wall Street. The number of students participating in corporate recruiting, which is heavily weighted toward consulting and banking, has dropped 32 percent from its peak in 1987. "The class of '88 used recruiting for experience and exposure, unlike earlier classes who 'had to get a job,'" says Dean Wright.

Two beneficiaries of this change are law schools and education. According to Marcia Craig of Dartmouth's Career & Employment Services office, the number of law-school applicants has increased by 16 percent since 1987. It's the "noncommittal" option, according to CES director Skip Sturman '70. "Law school has always been intensely appealing to students who aren't sure what they want to be next," he says. "I do not want to suggest that some students don't have the yearning or aptitude to be lawyers, but a lot of people take the law boards and if their scores are good that's reason enough."

The trend toward teaching, however, seems to reflect a genuine change in values. The number of students enrolled in the Education Department's teacher-preparation program has tripled in the last five years. At the core of the renewed interest in education is an awareness that public schools are not meeting the needs of the nation. "There is a sense of urgency for social programs that has permitted people to act who have always wanted to do something in the social services but felt they couldn't because of pressure from parents, friends, and society in general," says Faith Dunne.

Dean Wright offers anecdotal evidence from her experiences with the class of '88: "The fact that a really bright—as measured by grade point averageand intellectually curious male, and other men like him, express an interest in public-school teaching is an indication that the mainstream is no longer just interested in commercial banking," she says.

Skip Sturman is less willing to attribute the changes to a new trend on campus. "I would be hard put to say that students have abandoned Wall Street in droves and jumped on planes bound for Third World countries. The changes are more subtle," he says. He notes that employment statistics do not show an in- crease in students seeking nonprofit jobs. Instead, he believes that Dartmouth's graduating seniors are more afraid than ever to make commitment. "I'm keeping my options open" was the answer adopted by the class of '89, according to Sturman. "It was not unusual for a single student to apply to law school, do corporate recruiting, think about teaching, and then take the Foreign Service exam."... ...The scene is a Alpha Delta house meeting on a Wednesday night dur- ing summer term. As the proceedings drag on, a '9l flings a beer can in a high arc across the room into a gar- bage can. "Hey, don't do that," yells one of his brothers. "We recycle those."

Long regarded as the least progressive institutions on campus, fraternities and sororities have contributed the strength of the Greek system to the volunteer effort. Although some projects are clearly intended to placate the administration, most houses go above and beyond the community-service requirements set by the deans, according to Debbie Reinders, assistant dean of residential life. The Greeks participate in programs that range from swimming lessons for retarded children to softball games with orphans. The Tucker Foundation reports that in 1989 16 houses completed a total of 24 projects. Because most Greek social-service activities are done independently, the actual number of programs is probably much higher. For instance, The New York Times recendy ran a feature on the Wishing Well, a Dartmouth organization that grants wishes to children with life- threatening illness. David Sherwood '90 and Bill Levin '90, members of Tri-Kap and Zeta Psi, started the program and have since received financial and administrative support from the Coed, Fraternity, and Sorority Council.

Alpha Delta combines public service with the inanities of the Greek system every spring when the pledge class has its annual keg run. The class collects monetary pledges for local charities and then carries a keg (empty) on a broom handle while running in shifts the 11 miles to Lyme, New Hampshire. "It's a lot of work," says John Engleman '68, advisor to the house. "But I think the guys get a lot of enjoyment out of it, knowing that they are doing something good for the community."

The beer can flying across the Al pha Delta living room has other significance. It is one of the 500,000 cans that the Dartmouth community has recycled in the past year. (AD collected the most cans for recycling of any fraternity during the summer term, which, remarks one member wistfully, "probably just means that we drank more beer than any house on campus.") If the push to put a Macintosh computer in every dorm was indicative of priorities in the eighties, then the recycling bins for cans and newspapers all over campus, including a recycling room in every dorm, are signs of times to come. In a single year the Dartmouth Recycles program has boosted the percentage of the waste stream that is recovered from 2.6 percent to 12 percent. The initial impetus for the program was financial, says Bill Hochstin, assistant director of Building and Grounds and director of Dartmouth Recycling. Landfill costs in the Upper Valley have more than doubled in the past two years and are expected to continue skyrocketing. Since the program got started, however, the campus has supported the effort, and it has succeeded where other fledgling environmental programs have failed. Professor Andrew Friedland's class, "Earth as an Ecosystem," is testimony to the new awareness; enrollment has increased from 37 students in 1987 to 178 in 1989. "A lot of our classes have jumped up like that in the past few years," reports Janna Hinsley, senior secretary for the Environmental Studies Program.

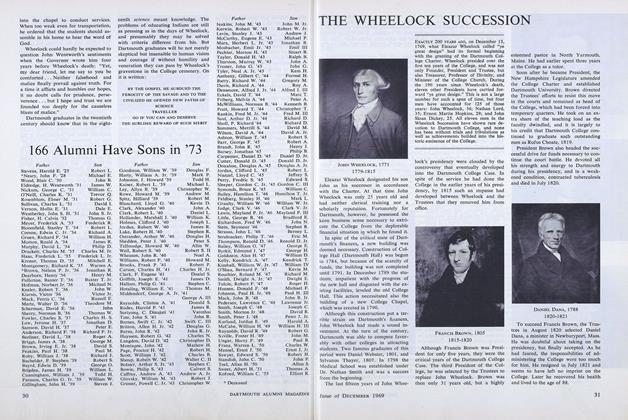

Susan Conroy '87 was the first Dartmouth student to spend a term assisting Mother Teresa in Calcutta, where she plunged into the depths of Indian poverty. "It has been a deeply moving, emotionally intense, and richly meaningful summer," she wrote after spending three months caring for children and adults ravaged by meningitis, dysentery, malaria, leprosy, and a host of other afflictions virtually unknown in the West. Despite her devotion to public service, however, her post-graduation plans were haunted by the specter of student loans. "I'm interested in serving the poor, particularly young children, but I'm obligated to meet some fairly hefty financial responsibilities," she wrote on a postgraduate survey.

She's not the only one. Fortune magazine reports that college seniors graduate with a combined $10 billion in school loans, "roughly what the entire country of Argentina owes to private U.S. banks." For some, the burden of debt makes postgraduate volunteer work, and the poor salaries that accompany it, all but impossible. "You can't write an article about careers in social service without mentioning student debt," says Skip Sturman. Corporate salaries dwarf those in education and the social services, and that is enough reason for some students to eschew public service. "It's never been the case where money has been the overriding factor for Dartmouth students," observes Sturman, "but it has always been in the top five."

Cynthia Marshall '88 found the corporate world very alluring during recruiting in 1988. "After growing up wanting to go into business, not knowing what I wanted to do while in school, and then receiving an offer that was an obscene amount of money for anyone just out of college, it was very hard to say no," she recalls.

After a year at one of the most prestigious Wall Street firms, though, the track to success was very clear and she wanted no part of it. "Do I like what I'm doing? Do I want a career here? Do I want to grow up like the people around me? The answer to all those questions was no."

She became one of the small minority who find their values at odds with the investment-banking lifestyle. "You have to check your idealism at the door if you want to survive," she maintains. "Otherwise you're going to lose out to somebody who doesn't have any." When the Dartmouth Admissions Office offered her a position, she made the leap from corporate America to college administration.

Most corporate execs would deny her thesis. Pamela Codispoti '88, for example, kept her idealism and her job, too. Despite the demands of her work as an associate consultant at Bain and Company in Boston, she is also a member of the Volunteer Fundraisers Association, an organization founded by a group of young Boston professionals in 1986. "Young people in Boston thought that they were getting a bad rap in terms of being out for number one, not caring about the community, etc.," explains Codispoti. The V.F.A., which includes young people from advertising, accounting, finance, and other high-powered businesses in Boston, holds two fundraisers a year and donates the money to a selected charity. Corporate sponsors donate money for overhead costs. The work follows the line of thinking of an applicant for a Dartmouth Peace Corps internship who wrote, "We cannot all devote our entire lives to public service, but in the long run an investment banker who actively encourages social programs is a very valuable tool."

The Dartmouth trend is in sync with national sentiment. A 1989 Gallup poll revealed that the number of Americans who considered it important to "work for the betterment of society" rose from 51 percent in 1981 to 69 percent in 1989. A similar poll showed that the number of Americans who actually participate in charity or social service increased from 27 percent of the population to 39 percent between 1977 and 1987.

Even those who blame the Reagan administration for fostering the "Yuppie Syndrome" concede that the former president placed a high priority on social service within the private sector. The Reagan years saw a call to voluntarism, although possibly at the expense of funded programs, Jan Tarjan says. George Bush and his "thousand points of light" have perpetuated this sentiment. "The signal Bush is sending is very positive. It's giving students permission to act on their altruism," says Tarjan. Fortune magazine reports that in 1988 applications for the Peace Corps were up 22 percent nationwide after reaching an all-time low in 1987.

Don't misread the signals. They don't exactly herald a rebirth of the sixties. (For one thing, haircuts are shorter than ever.) But Dartmouth clearly is at the forefront of what the Christian Science Monitor calls "a new wave of social responsibility washing across campuses in many parts of the United States." Every student who has tutored an inmate or shared an ice cream cone with an adopted little brother retains the experience. mi

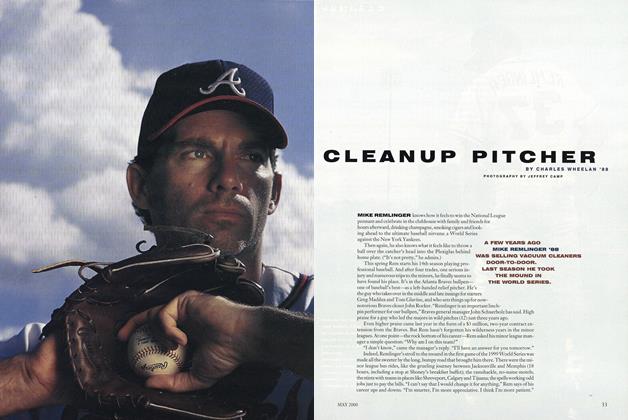

One of 40 students who tutor at a state prison, Alissa Burstein '91 offers some company from the outside.

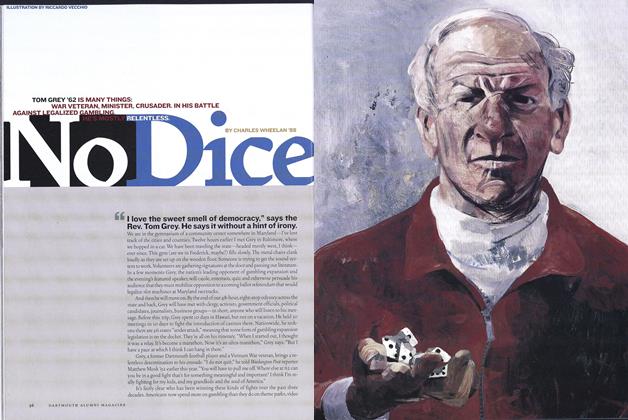

Mustafa Vahanvaty '88 and "little brother" Nick share puppy love on the Dartmouth Green,

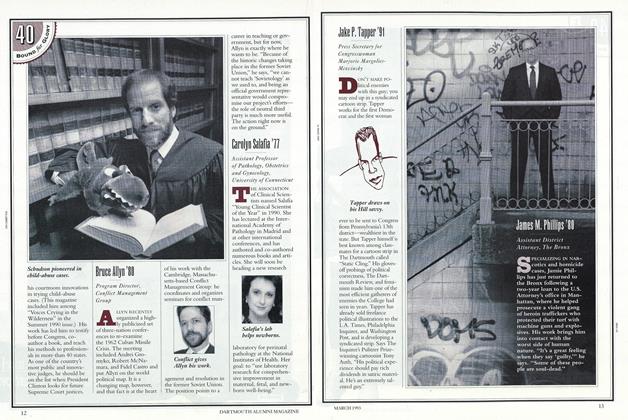

One of a thousand student volunteers, David O'Brien '91 drops off a Meal on Wheels.

When Susan Conroy '87 went to Calcutta in 1986 to help Mother Teresa, the Tucker Foundation funded the trip.

An eraof self-absorption.was beginning togive way tosomething kinderand gentler

Studentshave taughtEnglish to boatpeople in HongKong, implementeda program forwheelchair athleticsin Honduras, andcounseled drugaddicts inSingapore.

Longregarded as theleast progressiveinstitutions oncampus,fraternities andsororities havecontributed thestrength of the Greeksystem to thevolunteer effort.

Forsome, the burdenof debt makespostgraduatevolunteer workall butimpossible.

After graduating from Dartmouth in1988, Asian Sttidies major CharlesWheelan traveled around the world, writing dispatches for the local Valley News.This past November Charlie became thespeechwriter for another great Dartmouthidealist, Maine Governor John R. "Jock"McKernan '70.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePutting Words in the Mouths of the Great

December 1989 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

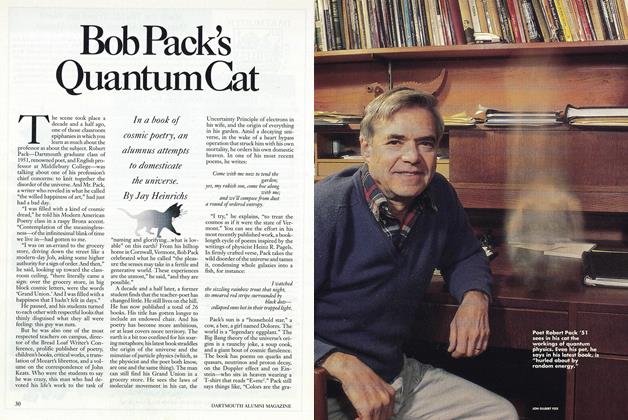

FeatureBob Pack's Quantum Cat

December 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

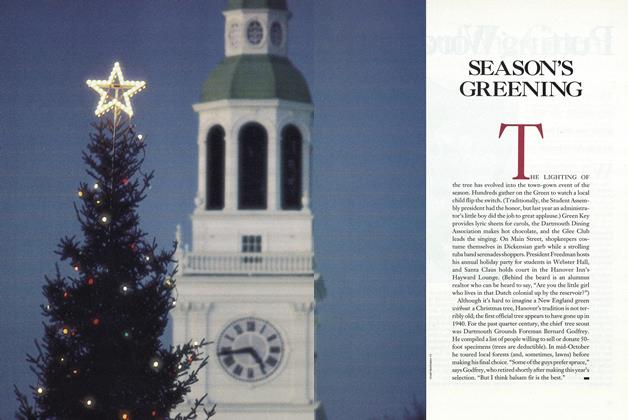

FeatureSEASON'S GREENING

December 1989 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

December 1989 -

Sports

SportsThe College's First Fan Picks a Winner

December 1989 By Noel Perrin -

Class Notes

Class Notes1958

December 1989 By Fred Louis 111