With every approach to deciphering myth, the plot thickens.

MYTH MEANS A VARIETY of things to a variety of people a widely held belief, a fiction masquerading as truth, an old wives' tale, or a profound truth expressed symbolically. In the study of religion, however, myth refers more specifically to a particular kind of story: a story, handed down orally from generation to generation, about the deeds of superhuman beings who can do things we humans cannot. Some mythical characters, such as Moses, Jesus, Krishna, and the Buddha are heroic, while others are not. The "Phi" of Thailand and the "Nats" of Burma, for example, are invisible beings who affect humans for good or ill, and in many cultures ancestors or other spirits have superhuman powers. Myths traditionally were part of a culture's oral tradition and subject to refinement and change over the years of telling and retelling. Modern-day tales of such superhumans as Superman and Batman often mimic the actions and powers of mythical characters, but as the literary products of specific authors these stories remain distinct from myth.

In many cultures myths are told only at specific sacred times by chiefs or religious leaders, whereas other stories such as folktales or legends about historical events or personsare told by anyone at any time. But whether or not they are reserved for special times, myths around the world share a puzzling paradox: in myth anything goes—after all, we are talking about superhumans yet the kinds of themes myths relate are surprisingly few in number. Myths tend to be limited to such topics as creation, miraculous birth, floods, wars, incest, and tests or physical ordeals. No one has yet fully explained the paucity of mythical themes, despite a wealth of interpretations of the meanings of myths and the cultural roles and functions myth fulfill. So diverse are the approaches to myth, in fact, that about the only thing most scholars of myth agree on is that we cannot take the existence and actions of superhuman beings literally.

One school of thought argues that the meaning of a myth can only be understood from the "original" or "genuine" form of the myth. For example, if you wanted to explain the meaning of the myth of Vishnu in Hinduism, you would focus on the history of the mythical tradition of Vishnu, tracing it back, perhaps to the Vedas. A problem with this historical approach, however, is that it is speculative; when dealing with an oral tradition we are seldom able to trace a myth back to its origin or determine which existing version of a myth is the earliest. Moreover, it rests on the false notion that the history of a myth constitutes its meaning.

An alternative historical approach sees myth as the projection or representation of real historical events or persons. Attempts to discover the historical Moses, or Jesus, or Buddha, or an actual war as the basis for the great Indian epic, the Mahabharata, are examples of this approach. But, knowledge of the historical Jesus, even if we could uncover it, does not explain the meaning, the significance, of the superhuman Jesus of myth. Further-more, this approach to myth assumes that myths must refer to historical facts or events in order to have meaning, and that if they do not, they are deceptions, fictions, or lies.

One of the more popular approaches to the study of myth views them as attempts to explain the world and our experience of it. Such myths especially those about the origin of the cosmos are interpreted as being similar to modern scientific theories that help us explain puzzles, answer questions, and provide us with predictions. While such myths are, of course, false explanations, it does not follow that the people who believe them are irrational. An explanation may well be false yet rational as an attempt at explanation. This rationalist or intellectualist approach provides the foundation for thinking of myth as false, as ideology, as appearance rather than fact, but leaves us with an unanswered question: Why do people persist in believing what is false?

Functionalist theories of myth, widely used in anthropology, psychology, sociology, and comparative religion, attempt to answer this question. Functionalism tells us that if we want to know the meaning of a myth we must look to what the myth does: the meaning of a myth is in its use. Myths function to satisfy essential needs of societies and individuals and will persist as long as these needs are satisfied. For example, some myths might function to help individuals overcome anxiety or crises while others function to provide coherence and order for the maintenance of society. Functionalists do not agree on just what the basic needs of society and individuals are, although most at least concur that social groups and individuals are unaware of the functions of their myths. There are two basic problems with functionalism. The first involves the vagueness of the term "need" as an important term in the theory. The second problem is more serious: recent criticism of the theory demonstrates that functionalist conclusions are either invalid or trivial.

Probing the unconscious level of myths is the undertaking of symbolic analysis, which regards myths as symbolic expressions of abstract meanings, psychological repressions, complex collective structures, metaphysical archetypes, or some transcendent reality that is often defined as the sacred. Symbolic analysis of myths attempts to translate the symbols into the actual reality that they refer to. The works of Durkheim, Freud, Jung, and Eliade are classic examples of symbolic analyses of myth, although these theorists would profoundly disagree on just what the reality is that myths refer to.

The assumption underlying symbolic analysis is that myths have a hidden meaning that must be deciphered or decoded. The task, then, is to interpret the hidden message. But symbolic analysts have not answered the question of why societies and individuals persist in speaking in a coded language a question that becomes more troublesome when we read that the people who use this coded language are not aware of the "real" meaning of the myths they tell since the meaning is hidden!

Another type of symbolic analysis views myths as symbolic representations of social structures. Thus if we have a set of myths from a particular society, we should be able to deduce the social structure from the myths, a methodology that would be particularly useful in studying societies that no longer exist. But myths are not always accurate maps of a social terrain. Indeed, the details in myths are often just the reverse of the actual social structures of the society that tell them. For example, most cultures prohibit incest, yet many myths describe incestuous relations between superhuman beings. In the end, symbolic theory remains conjectural, especially in the case of myths from vanished cultures.

Inversions and oppositions lie at the heart of yet another approach to myth: structuralism. Heavily indebted to modern linguistics, structuralism views myths as logical mechanisms for thought. Levi-Strauss, a key proponent of structuralism, defines myths as stories that attempt to overcome contradictions or oppositions. He argues that the meaning of myths is not to be found on the surface but in the set of opposites within the myths. One of the most successful examples of this type of explanation is his analysis of "The Story of Asdiwal," a myth which begins with a mother and daughter meeting down in a valley and ends with a father and son up a mountain.

Yet if structuralists are correct that myths are cognitive structures through which we think and that the meaning of a myth is identical with its structure, then the language of myths operates very differently from ordinary language. Linguists can easily demonstrate that semantics (meaning) and syntax (structure) are not identical. "Green ideas sleep furiously" is a well formed sentence syntactically, but meaningless as a sentence in ordinary English. Structuralists have yet to explain why this is not the case in myths. What we need is a semantic theory what will complete the structuralist base for explaining myth. The theory may include the proposition that myths have meaning without referring to anything!

Given the shortcomings of any one theory, it is often tempting to make use of all of these approaches to myth. The problem with "methodological eclecticism," however, is that it does not tell us which theory to use for explaining a specific myth, nor does it show us how to avoid becoming incoherent, given the fact that many of the theories are incompatible with, and often contradict, each other.

And so the search continues. The only theoretical certainty thus far is that the meaning of myths does not rest on the surface. Elusive as ever, myth remains one of the ongoing mysteries of human culture.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePARTYING: A PEER REVIEW

May 1992 By John Scalzi -

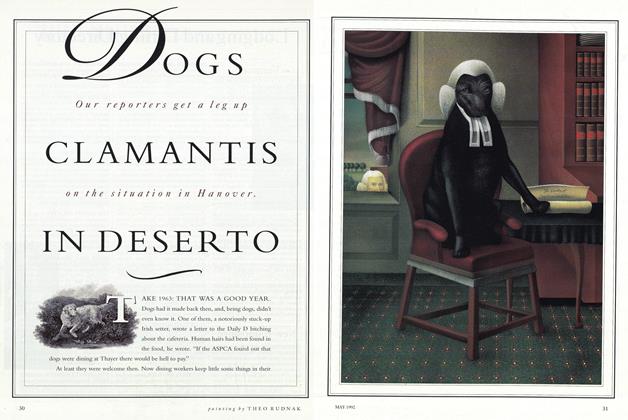

Cover Story

Cover StoryDogs Clamantis in Deserto

May 1992 -

Feature

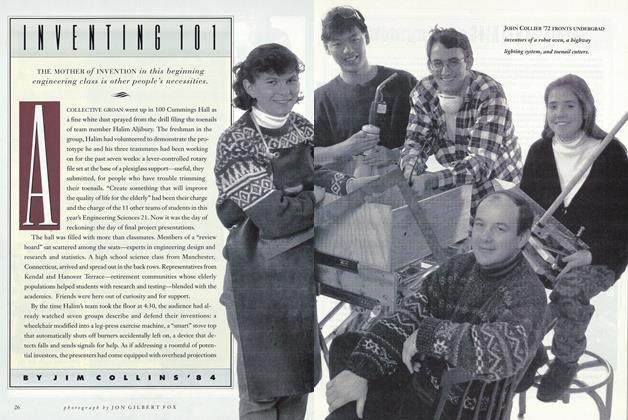

FeatureINVENTING 101

May 1992 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Feature

FeatureOh, You Shouldn't Have!

May 1992 By JONATHAN DOUGLAS -

Cover Story

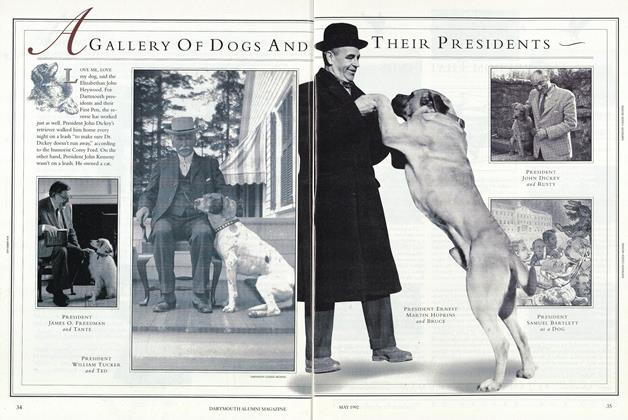

Cover StoryA Gallery Of Dogs And Their Presidents

May 1992 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

May 1992 By Wheelock

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE EARLIEST

November, 1922 -

Article

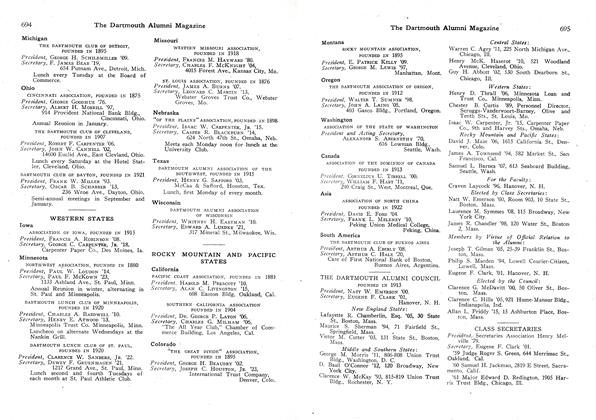

ArticleROCKY MOUNTAIN AND PACIFIC: STATES

June 1925 -

Article

ArticleThayer School Contributors

December 1956 -

Article

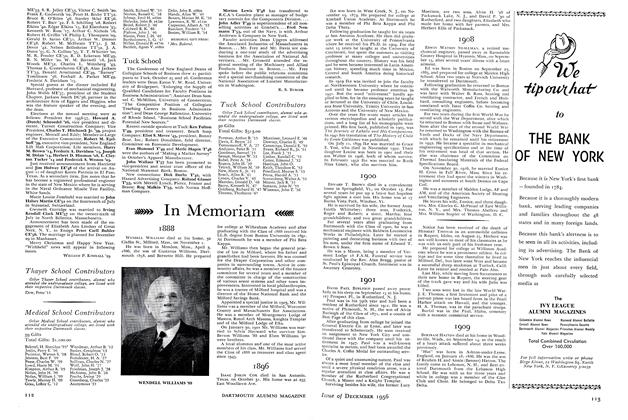

ArticleIn this picture John C. Parish '36

APRIL 1978 -

Article

ArticleIn Harmony

SEPTEMBER 1997 By MICHELLE GREGG '99 -

Article

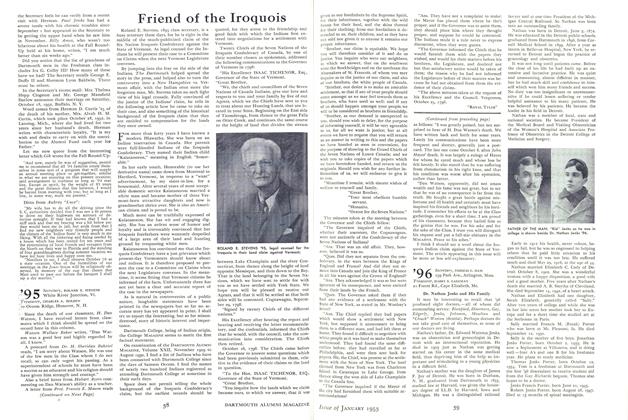

ArticleFriend of the Iroquois

January 1953 By Royal Tyler