THE MOTHER of INVENTION in this beginning engineering class is other people's necessities.

A COLLECTIVE GROAN went up in 100 Cummings Hall as a fine white dust sprayed from the drill filing the toenails of team member Halim Aljibury. The freshman in the group, Halim had volunteered to demonstrate the pro- I totype he and his three teammates had been working on for the past seven weeks: a lever-controlled rotary file set at the base of a plexiglass support—useful, they submitted, for people who have trouble trimming their toenails. "Create something that will improve the quality of life for the elderly" had been their charge and the charge of the 11 other teams of students in this year's Engineering Sciences 21. Now it was the day of reckoning: the day of final project presentations.

The hall was filled with more than classmates. Members of a "review board" sat scattered among the seats experts in engineering design and research and statistics. A high school science class from Manchester, Connecticut, arrived and spread out in the back rows. Representatives from Kendal and Hanover Terrace retirement communities whose elderly populations helped students with research and testing blended with the academics. Friends were here out of curiosity and for support.

By the time Halim's team took the floor at 4:30, the audience had already watched seven groups describe and defend their inventions: a wheelchair modified into a leg-press exercise machine, a "smart" stove top that automatically shuts off burners accidentally left on, a device that detects falls and sends signals for help. As if addressing a roomful of potential investors, the presenters had come equipped with overhead projections showing circuitry flow charts and cost revenue analyses. They made a case for the niches their products would fill, talked about marketing plans, showed results of computer modeling, played videotapes of their products in actual use. In dark suits or knee-length skirts, the students dressed as if they cared.

The review board, though, was not here to be easily impressed. If they were the potential investors, then they wanted to make sure they were investing their money wisely. Questions came from all corners of the room as die presentations ended. "Have you done a patent search?" Vic Suprenant, research engineer at Thayer, wanted to know. "Why a computer chip instead of magnetic tape?" asked colleague Doug Fraser. "Can the timer be overridden?" wondered engineering department chair A Converse. "Did people actually use the stove at Kendal?" ques- tioned machine shop supervisor Roger Howes.

And now white dust was flying up from Halim Aljibury's toes.

"That's no joke," said senior teammate Robert Lussky, playing the crowd like a confidence man. "Imagine how demeaning it is for an elderly person to have someone else file his nails. We talked with one podiatrist who wears a mask when he's making his calls, and another one who returns from his visits covered head to foot with toenail dust..." For the second time, the roomful of potential investors groaned.

ES 21 HAS BEEN PRODUCING INVENTIONS at Dartmouth since the 1960s. For the past ten years it has been taught by a pleasant, unassuming professor named John Collier '72, Th' 77. "I took the course myself back in 1970, under Robert Dean," Collier recalls. "We had to do something involving construction techniques, and my group made a kind of moveable wall that had adjustable outlets, was soundproof the whole works. That course made an impression on me; it introduced problem- solving in such a concrete way."

As it turned out, Collier's group received an "A" for their project but they never pursued it beyond the class. A student-designed artificial arm, however, evolved into an industry standard. A pilotless gas stove—using a piezo-electric crystal was created here and later mass-produced by non-Dartmouth graduates. An energy-measuring device created last year is in the process of being patented and incorporated into a business by a Tuck School entrepreneurial group. Dean Spatz '67 and his group invented a "reverseosmosis" machine that revolutionized the process of maple sugaring; his company Osmotics, according to a 1991 issue of Forbes magazine, is now worth $22 million.

Commercial success, though, is not the aim of the class, according to Collier. "The goal is simply to introduce engineering to students who have little background. And we want more than a paper or computer program to come out of the class. We want students to build something, to get dirty, to know how hard it is to drill a hole where you want it." Each year the class is presented with an open-ended problem to solve: themes have ranged from energy conservation to highway safety to extending the growing season to this year's goal of improving the lives of the elderly.

At the start of each course, students are familiarized with the various shops and labs at Thayer and in the Hopkins Center. Once students have been grouped into teams and assigned advisors, they are on their own to a surprising degree, armed with a warm-up "mini-project," a $500 budget, and the use of a free telephone. The actual designing and building take place outside of the classroom; classes are devoted, meanwhile, to patent and literature searches, issues of ethics and liability, and economics. (This year was the first in which spreadsheets were required in the final presentations.) Occasionally experts are brought in from the outside for guest lectures.

This year's class, according to Collier, was better than average. "They took on more difficult ideas," he says, "and they had more variables and logistics to contend with—things like working with stroke patients and coordinating meetings with doctors and physical therapists."

A review board annually awards a $600 prize to the best proposal coming out of the course. Alas, the '91 board passed over the toenail filer and chose instead a memory aiding device that allows voice messages to be played back on specified days and times—reminding the elderly user of a daughter's birthday, for instance, or to take the turkey out of the oven at 2:00. The prototype was fabricated from two telephone answering machines, an alarm clock, a computer chip, and some creative electronics. "That group was incredible," says Collier. "They got into things like speech compression and the frequency range of the human voice, they tested their product against a series of alternatives, they set a low production-cost challenge and they met it. Frankly, I didn't think it could be done."

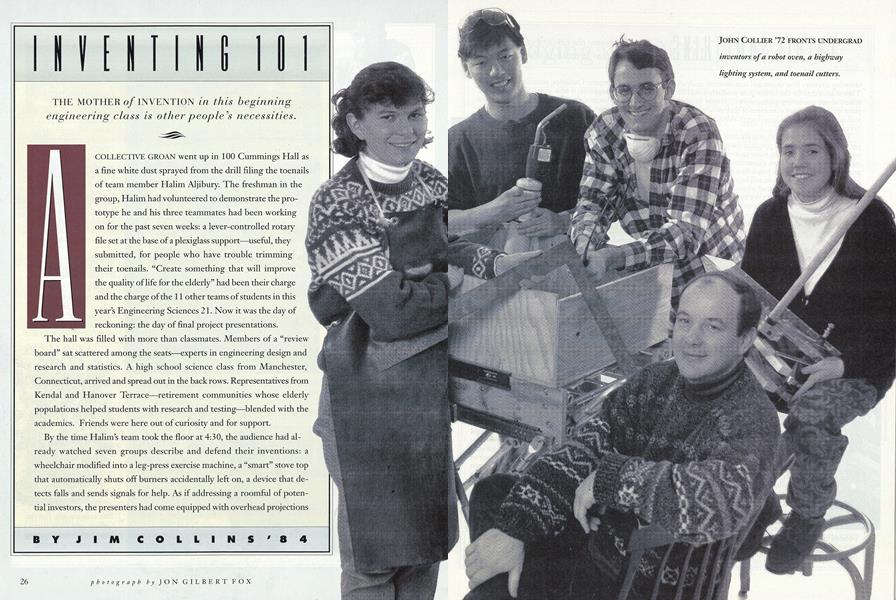

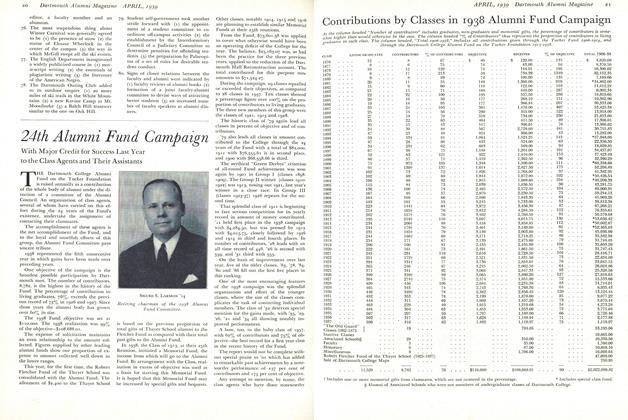

JOHN COLLIER '72 FRONTS UNDERGRAD inventors of a robot oven, a highwaylighting system, and toenail cutters.

The stovetopshuts itself off.

Elderly aid: anexercise wheelchair.

"CREATE SOMETING that will improve the quality of life forthe elderly" had been their charge...

Jim Collins is a contributing editor of this magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeaturePARTYING: A PEER REVIEW

May 1992 By John Scalzi -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDogs Clamantis in Deserto

May 1992 -

Feature

FeatureOh, You Shouldn't Have!

May 1992 By JONATHAN DOUGLAS -

Cover Story

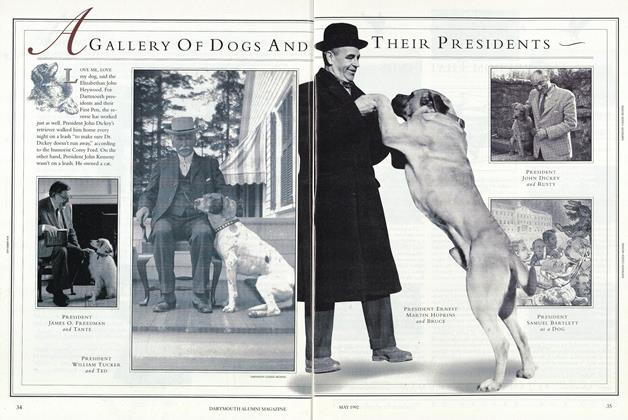

Cover StoryA Gallery Of Dogs And Their Presidents

May 1992 -

Article

ArticleIf Only it Ware Just a Myth

May 1992 By Professor Hans H. Penner -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

May 1992 By Wheelock

JIM COLLINS '84

-

Feature

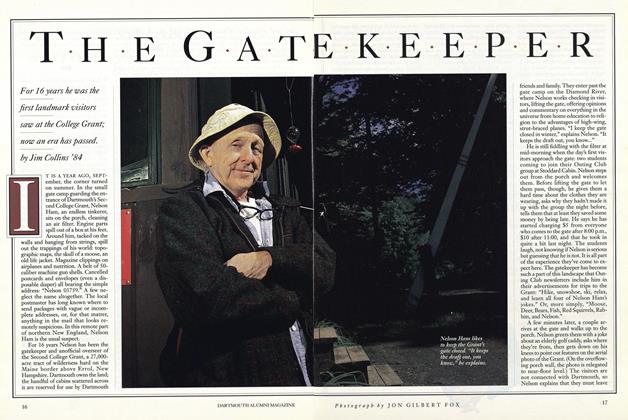

FeatureThe Gate keeper

SEPTEMBER 1991 By Jim Collins '84 -

Article

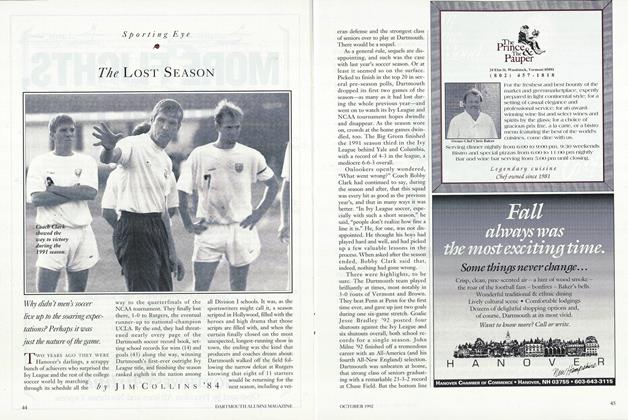

ArticleThe Lost Season

October 1992 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Article

ArticleBaseball and the Pursuit of Innocence

June 1995 By Jim Collins '84 -

Article

ArticleThe Role of an Intellectual

JANUARY 1998 By Jim Collins '84 -

Cover Story

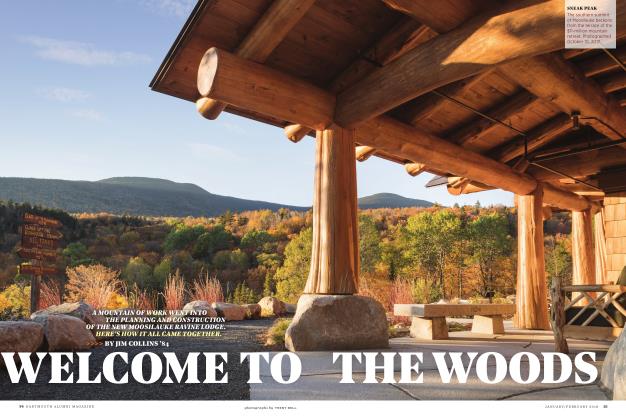

Cover StoryWelcome to the Woods

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2018 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Features

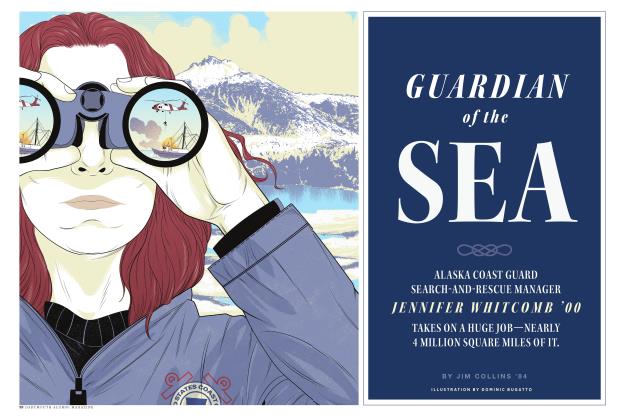

FeaturesGuardian of the Sea

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2025 By JIM COLLINS '84

Features

-

Feature

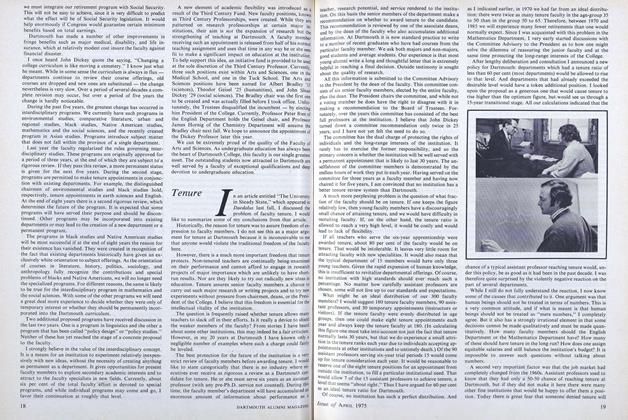

FeatureContributions by Classes in 1938 Alumni Fund Campaign

April 1939 -

Feature

FeatureTenure

April 1975 -

Feature

FeatureDecision Making

April 1975 -

Feature

FeatureThe Senior Valedictory

JULY 1970 By CRAIG JOYCE '70 -

Feature

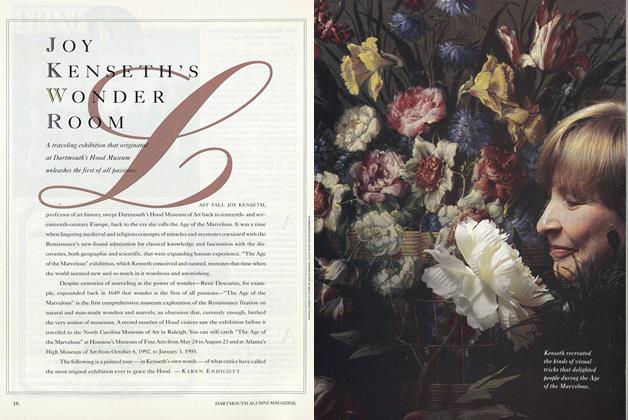

FeatureJoy Kenseth's Wonder Room

APRIL 1992 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1956

July 1956 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY