The verdant foresthides a bloodytrail of greed.

WE WOULD FIND MANY rivers to cross. So I warned the freshman group as I mapped out the course that lay ahead for our seminar on rainforest narratives. Southern rivers with names such as Parana, Orinoco, Vichada, Madeira, and, of course, the Amazon. But perhaps the most important river to cross would be the imaginary one that divides our consciousness neatly between North and South, us and them, here and there, and reduces a cataclysm or an injustice taking place outside the boundaries of here, North, and us into a distant and unrelated event, a mere electronic signal on the television screen.

Narratives of the rainforest invariably take their readers into the realm of fiction by means of imposing waterways or the arteries of the living system of the Amazon basin. The Amazon has more than a thousand tributaries, many more than a thousand miles long, many larger than the Mississippi. Often, the forking channels and currents that intersect in actual geographical space become, in the fiction, a labyrinth: a metaphor for a world bewildering in its immensity, unsettling in its storms, swamps, carnivorous fish, ancient trees, parasitic vegetation, poisonous snakes, dangerous insects, butterflies in myriad colors and sizes, and astounding birds.

Descriptions of the Amazon invariably turn hyperbolic as they try to capture the profusion of forms and wonders of an environment that since the conquest has continued to symbolize the uniqueness of the New World. In "The Making of Fitzcarraldo," German filmmaker Werner Herzog calls the rainforest "an unfinished country." It is a land, he says, "where God, if he exists, has created in anger. It's the only land...where creation is unfinished yet." Herzog's delivery is laden with impotence and anguish. The jungle has denied him some dear principle of harmony, a principle conceived elsewhere but untenable in the actual conditions of the Amazonian landscape. And yet, Herzog admits, he is full of admiration for the jungle. He loves it, against his better judgment.

Even Herzog's choice of the word "jungle" reveals this European ambivalence. Jungle derives from the Hindustani word djanghael, which means wasteland and originally referred to dry, scrubby thickets. "Rainforest," the more appropriate word for the tropical forest, is a 1903 translation by William Rogers Fisher of the German word Regenwald, first used by the botanist Andreas Franz Wilhelm Schimper in 1898. In imaginative terms, jungle seems to carry a far richer symbolic load than the environmentally correct

The chaotic nature of the "unfinished country"—the Amazon basin actually includes nine South American nations—does not preclude us from attempting to map the journeys of the protagonists of rainforest narratives. Each journey represents a will to find something or someone, perhaps the protagonist's own self, in a place radically different from the space of civilization. The narratives record, in veiled fashion at times, the points along a journey where fiction and geography meet and the differences between them blur. In class we attempt to map these journeys, to test our competence in seeing the connections of place and imagination, and, conversely, to recover the geography from behind the fiction in order to transfer the world of the narrated past into our present.

Journey and quest, the principal motifs of the longer narratives, provide the means to expose conflicts between man and nature, and, just as importantly, between man and his own nature. Narratives of the rainforest are also a record of man's inhumanity to man. Beginning with Carvajal's chronicle of the discovery of the Amazon in 1541, these stories speak of human bondage and exploitation. The brutal descriptions by Quiroga of the injustices perpetrated in logging camps, the inhumane treatment of the rubber tappers reported by Rivera and Ferreira de Castro, the outrages of the rubber plantation and the gold mines of Venezuela decried by Gallegos are all living testimony to a bloody trail of greed in the verdant forest.

Literary studies have tended to emphasize historical contexts of fictional works, and to focus on what happens in the text in terms of time rather than space. But the study of rainforest narratives makes evident the importance of landscape depiction in literature. In focusing our attention on characters' experiences of the environment, our class used place as the organizing critical principle for our immersion into the stories of the rainforest. Concentrating on space is a mighty challenge in itself: a task akin to blocking out the actors and the interpersonal drama in a movie in order to concentrate on the setting, the decor, the backdrops. It feels unnatural, since the eye itself seems to follow motion, entrances, departures. For example, in following the drama of war, with its acts of heroism and tragedy, relentless activity, and strategic maneuvers, we allow the space of the action to become the background, the something that is incidentally defoliated, razed, and bombed in the battles against the antagonists. Making amends with the space comes later, when the dust settles, if it ever does. Theorists have proposed that just as the stability of the physical world anchors human experience, our sense of reality in fiction is grounded in the setting. Paradoxically, in literature, as in movies, setting is the very element that we usually take for granted.

Yet landscape depiction by a skillful novelist comes closer to capturing the full effect of the environment than any objective treatise ever could. Narratives of the rainforest burst with the magnificence of the setting. Even what has been loosely termed "magic realism" in South American writing has its roots in a special relationship with the Amazonian environment. The earliest explorers saw their newly expanded world as a place where fantastic adventures could take place and incredible beings could be found. The Amazon women who season Carvajal's account of the discovery of the largest river in the world were real in the explorer's mind. The vast possibilities of the place, the excitement of the enterprise, and the drive to beguile others to launch a thousand expeditions caused historical events and creative literature to meet and merge. Even three hundred years after Carvajal, the botanist Richard Spruce would note reports of the fabled Amazons' existence, and von Humboldt before him would comment skeptically about the existence of the Rayas, a tribe of

Amazonian people with mouths in their navels. Carpentier's report of seeing a cloud of amaranth-colored butterflies in the Amazon becomes Garcia Marquez's fantastic event in the fictional town of Macondo. Similarly, Gallegos's intimation of his protagonist's ability to turn into a tree at will presages the full-blown presence of the marvelous in Garcia Marquez's fiction. Indeed, "magic realism" appropriates some real or imagined characteristics of the New World and their representation and incorporates them in an otherwise believable stoiy. The reader is left to determine what to believe or disbelieve of an account that is ultimately designed to astonish.

Beyond magic realism, our understanding of the rainforest has drastically changed since the earliest chronicles. Just as the term "jungle" has given way to "rainforest," so has the rainforest become the lungs of the world. Our increasing knowledge and understanding of the rainforest makes it a more familiar place. The correlate in fiction is a more benign representation of the forest: the relationship between the forest and man, once fraught with hostility, has been transformed into an order where man can and has cohabitated with flora and fauna, subtly changing himself and the environment in the process.

Indeed, in the novels we read that the forest plays a key role in shaping the characters, who must resort to their innermost strengths to deal with the primal power of the rainforest setting. The degree in which the forest influences the protagonists' search, however, has progressively diminished over time in each subsequent novel, to the point that in Carpentier's The LostSteps, for example, a previously threatening jungle is seen as an exotic space, or civilization's other. Progressively diminishing also is the real space of the rainforest. In fiction, while we read aggressively following our objective on our way to the end, the setting is telling us something obliquely, unheeded, and quietly supporting our drive. In the setting, there is a message about a humanity and a ground commonly shared between author and reader. The demise of rainforest will be an ecological disaster; it will also be the loss of a vital setting that is part of our common human history.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

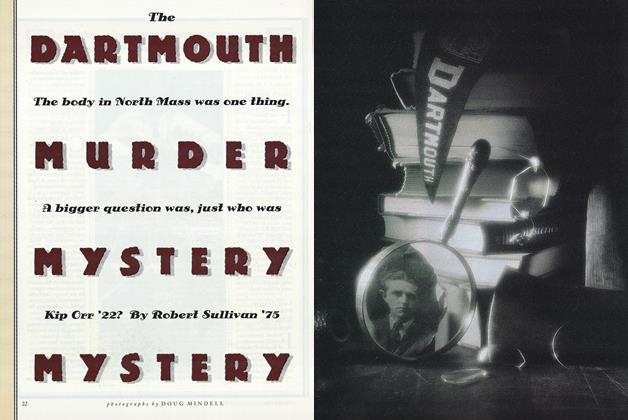

Cover StoryThe Dartmouth Murder Mystery Mystery

June 1992 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureFloating Home

June 1992 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

FeatureLast Person Rural

June 1992 By Noel Perrin -

Feature

FeatureThe Woman Who Was Not All There

June 1992 By Paula Sharp '79 -

Feature

FeatureWhy in The World: Adventures in Geograhy

June 1992 By George J. Demko with Jerome Agel and Eugene Boe -

Feature

FeatureMurder on Wheels

June 1992 By Valerie Frankel '87