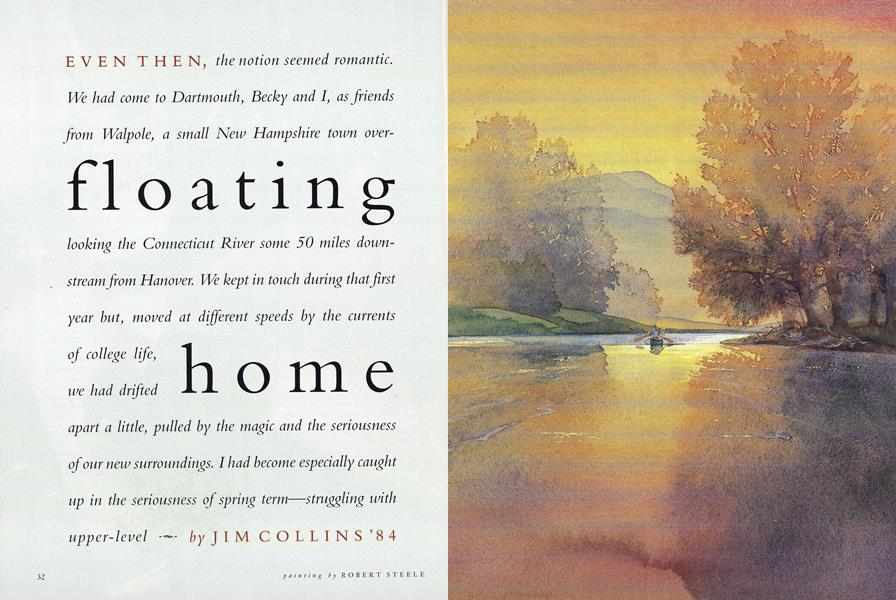

EVEN THEN, the notion seemed romantic.We had come to Dartmouth, Becky and I, as friendsfrom Walpole, a small New Hampshire town overlooking the Connecticut River some 50 miles down-stream from Hanover. We kept in touch during that firstyear but, moved at different speeds by the currentsof college life,we had driftedapart a little, pulled by the magic and the seriousnessof our new surroundings. I had become especially caughtup in the seriousness of spring term—struggling withupper-level Spanish, struggling with the varsity baseball team. Then it was near the end of the term and Becky suggested that, when it was over, we canoe home.

It was one of those implausible ideas that got better the more I thought about it. I liked the thought of walking out of my last exam at 11:00 and being on the river at noon. I liked the rhythm it would give to the year quiet time for reflecting on nine months' worth of stimulus, time to take a deep breath before starting into the routine of summer work. I liked the spirit of it, and the style. And, as the term wound down, I found myself distracted by the thought that it was Becky I would be making the trip with, and I liked that, too.

We met at Thayer for our final meal as freshmen, then walked our gear to the dock at Ledyard. Becky's father had left her canoe a 16-foot Old Town when he picked up her dorm-things in the family wagon. The June air was hazy and warm as we slipped into the water and pushed off, Becky in the bow. By Titcomb Island we were in T-shirts and shorts, down to our bathing suits by Wilder Dam. The smells of summer and suntan lotion floated with us, while the campus drifted farther and farther away and then was gone altogether.

Below the dam the current became stronger. The canoe glided over the shallow water, and we both took breaks from paddling to run our hands through it. We talked about school, and friends, and let silences settle in when our thoughts wandered. The sun caught an occasional car moving behind the trees along Route 12A. On the Vermont side, railroad tracks touched the river and disappeared into the woods.

At West Lebanon the Mascoma River came in on our left, and the landscape fell away. The Interstate arched overhead, framing industry on the river banks: the backsides of shopping centers, the gravel pits of the Readi-Mix plant, Lebanon's airport on a high hill, and, closer, its landfill. And then just as suddenly the shores were wooded again. A horse pasture opened around a corner here, the tip of Mount Ascutney there. We turned where the Ottaquechee joins the big river, following it back to a covered bridge, and saw beavers working on a lodge. Below the black straps of Becky's bathing suit the first blush of color began to show.

We heard the rapids at Hartland long before we saw them. For a moment we considered running the white-water, but in the end we took the sign's warning and carried ried the quarter-mile instead taking no chances with a loosely packed load of sleeping bags, tent, clothes, and food. We sat for a while before putting back in, the shadows lengthening, the two of us quiet, eating trail mix and listening to the rush of the water.

Back in the canoe, we scouted the banks for a campsite: in a clearing would be nice, we thought, with a view of the setting sun. Or a sheltered spot in a cove facing east, with a sandy beach for swimming. Just around the next bend, we'd say, and then the next. As the sun dropped, unfortunately, our standards did not, and we ran out of daylight still searching for the perfect place. We were on the edge of irritation and almost into Windsor when we finally agreed to settle for the next flat spot we saw.

It came, as it turned out, on a high bluff on the western shore, as lovely a spot as we had hoped for. A bank had been cut into a sandy cliff over the years, and a gradual base at one end was just right for beaching the canoe. On top, a small grassy area spread back into woods. In the dark, we could just make out the broad outline of the New Hampshire hills across the water. The setting felt remote and private and perfect. Becky smiled at me. The tension eased; we didn't even mind gathering wood and cooking by flashlight. And later, as we sat and looked out over the dying fire, I felt something pulling at me that was greater than the current flowing silently by.

We talked into the night. At 4:30 a.m., when we were in deepest sleep, the tent exploded. Noise, engines, metal grinding metal. An earthquake No! noise disoriented blackness pulsing shock electrocution No! a train! Beneath us. Boring through a tunnel under the tent...wind shaking noise what! blackness metal grinding metal death right through the tent, right through us! No behind the tent! Wide awake what! hearts pounding Right behind the tent!

Terrifying seconds passed before we realized what was happening. The roar continued. We groped for the flashlight, unable to talk over the noise. We turned it on, alert now, for the first time hearing the cadence of the metal. A train. Our perfect site was 20 feet from a train track. Then the grinding suddenly changed, pulled past us. Air sucked in behind the sound, shaking the tent, straining the moorings. We looked at each other, hearts still pounding, the sounds of engine and clattering ringing in our ears but diminishing, growing duller: The Montrealer, crashing though the night on its way to White River!

At some point we breathed again. We kept the flash-light on behind a water bottle to soften the glare, and talked to let energy out, to relax, for company. Eventually our pulses and adrenaline returned to normal. Eventually we fell back asleep. Neither of us had been in danger, but we would both remember the moment as the nearest to dying we had ever come.

WE AWOKE A FEW hours later to rain and dreary gray, and felt oddly unconcerned. We ate oatmeal and fruit in our sleeping bags, traded much-needed shoulder rubs, went swimming in the warm rain. By noon it had let up; an hour later we were back on the river under blue skies, Becky now in the stern.

We fell naturally into the rhythm of the paddles. Talk about college flowed into talk about high school and on back to childhood. Becky taught me songs she'd learned growing up—"Froggie Went A-Courtin'," "The Fox on the Town-O,"—and Ithought of Huck and Jim taking their raft down the Mississippi, and the time Jeff Hubbard and I skipped class in eighth grade to walk down to the river and watch the high water carry away the sticks we threw in.

We pulled out just above the long Windsor-Cornish covered bridge for a late picnic lunch, which we ate in a meadow surrounded by timothy and purple vetch and the view of Ascutney that once inspired Maxfield Parrish and other artists in the Cornish colony. We made our way past the bridge and, farther downstream, past the mouth of the rocky-bottomed Sugar River. Plenty of daylight remained when we landed the canoe and went in search of our second campsite. The choice was a change of pace: the edge of a pasture well back from the river, with tall grass for a mattress and Ascutney staring straight at us through the tent flaps. Not a railroad track in sight. We fell asleep that night under a starry sky, the air cooler now and filled with the night-songs of woodcock and crickets.

Becky awoke early the next morning to the cry of a red-tailed hawk. She nudged me awake, then opened the tent and searched the sky, finding the hawk in the brightness over the river. It was when she dropped her gaze that we received our second surprise in as many mornings: a dozen cows and a bull, apparently angry, stood in a semi-circle around the tent, staring at it. I came and looked. The bull was huge. "Oh, God," I thought. "We'll be killed in some farmer's pasture." I felt vaguely absurd, but vaguely scared, too. Becky said she was glad the tent wasn't red.

We tried staring the cattle down, which lasted a little too long for comfort. We estimated how much time it would take us to bolt from the tent to the safety of the birches at the edge of the pasture, and wondered how long it would take the bull. We lobbed prunes at the cows which caused a momentary retreat, but then, more curious, they moved back in even closer. We decided to wait them out. We ate breakfast inside (again) and laughed at the predicament, periodically checking the enemy. We lounged and read out loud, then looked again and saw the cows scattered across the pasture, indifferently chewing their cud among dried cow flops we had somehow failed to notice the evening before.

The final stretch to Walpole was as lazy as our morning had been. The current slowed through the giant oxbow at Weathersfield, where we swam near a cliff full of swallow holes. It picked up only slightly past Fort Number Four, then turned to deadwater three miles back from the Bellows Falls dam. We paddled along the setbacks, feeling smooth and powerful and in sync, and talked about each other and ourselves, the river bringing us together as it brought us home.

The trip ended on the North Walpole side of the dam, where Becky called her father to pick us up. We sat with our backs against the canoe, watching the river, and waited for him. Becky took my hand. I felt alive, changed. My first year at college—difficult and strange and wonderful—was officially over. And now something equally strange and wonderful was beginning. For the first time in my life, I was falling in love.

talk about college flowe into talk about highschool and on backto childhood.

we tried staring the cattle down, whichlasted a little too long for comfort.

JIM COLLINS, a contributing editor both to thismagazine and to Yankee, now owns two canoes and since hisfreshman year has made three more extended trips on theConnecticut—none, he says, as memorable as the first. Beckyis Rebecca Todd '84, an attorney with the Sierra Club LegalDefense Fund in Seattle. Her last paddle was a sea-kayaking trip with her mother up Glacier Bay, Alaska, where theyworried about grizzlies instead of cows.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

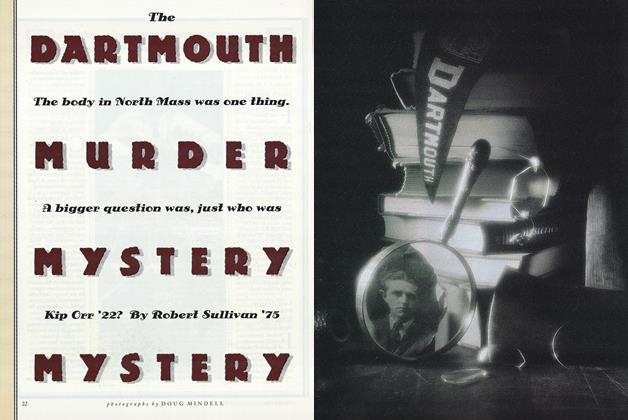

Cover StoryThe Dartmouth Murder Mystery Mystery

June 1992 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureLast Person Rural

June 1992 By Noel Perrin -

Feature

FeatureThe Woman Who Was Not All There

June 1992 By Paula Sharp '79 -

Feature

FeatureWhy in The World: Adventures in Geograhy

June 1992 By George J. Demko with Jerome Agel and Eugene Boe -

Feature

FeatureMurder on Wheels

June 1992 By Valerie Frankel '87 -

Feature

FeatureFenway: an Unexpurgated History of The Boston Red Sox

June 1992 By Peter Golenbock '67

Jim Collins '84

-

Feature

FeaturePeter Blodgutt, Adventure Librarian

October 1995 By Jim Collins '84 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryANDREW WEIBRECHT '09

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2014 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

FEATURE

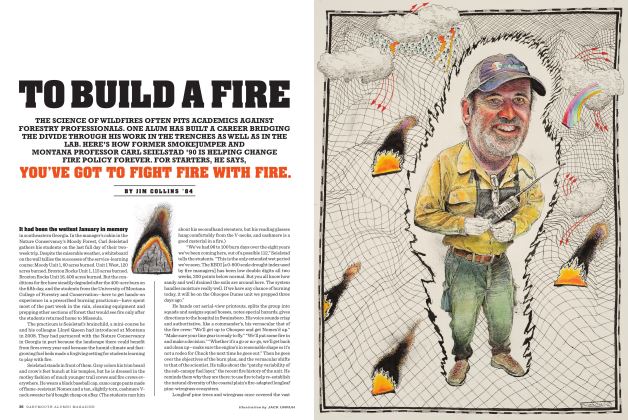

FEATURETo Build a Fire

JULY | AUGUST 2015 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

FEATURES

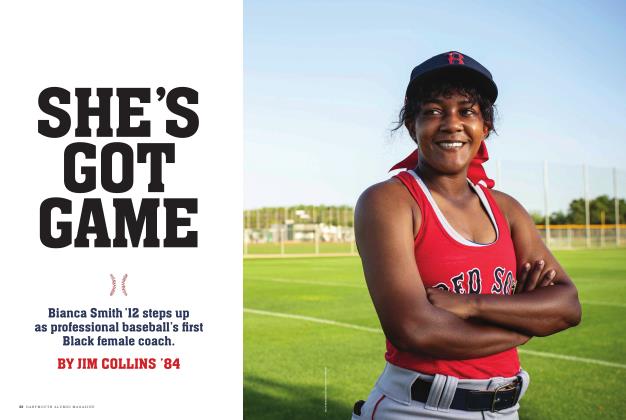

FEATURESShe’s Got Game

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2021 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Sports

SportsMoneyball

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2021 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Features

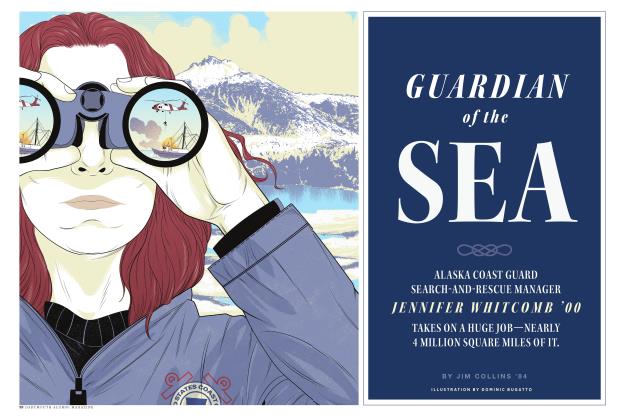

FeaturesGuardian of the Sea

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2025 By JIM COLLINS '84

Features

-

Feature

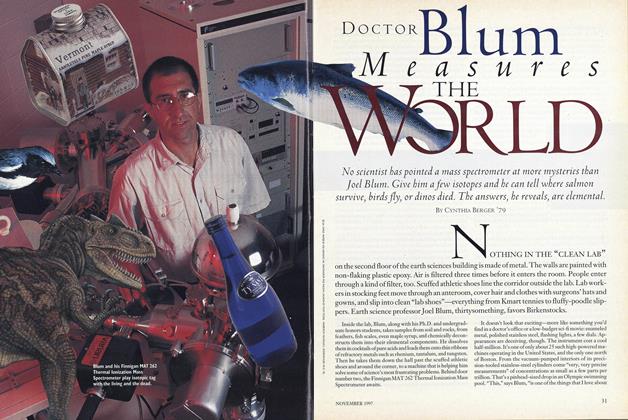

FeatureDoctor Blum Measures the World

NOVEMBER 1997 By Cynthia Berger '79 -

Feature

FeatureBraving the Alps

MARCH 1984 By Jack Aley '66 -

Feature

FeatureA MEMORANDUM

May 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureThe U.S.-Canadian Relationship

DECEMBER 1972 By JOHN SLOAN DICKEY '29 -

Feature

FeatureJourney's End: The Assyrian Reliefs at Dartmouth

SEPTEMBER 1985 By Judith Lerner -

Feature

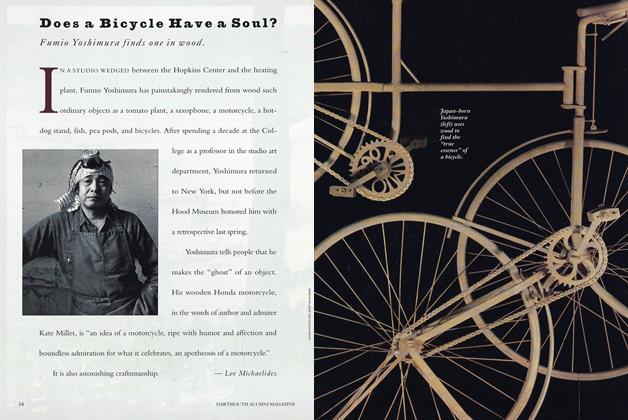

FeatureDoes a Bicycle Have a Soul?

June 1993 By Lee Michaelides