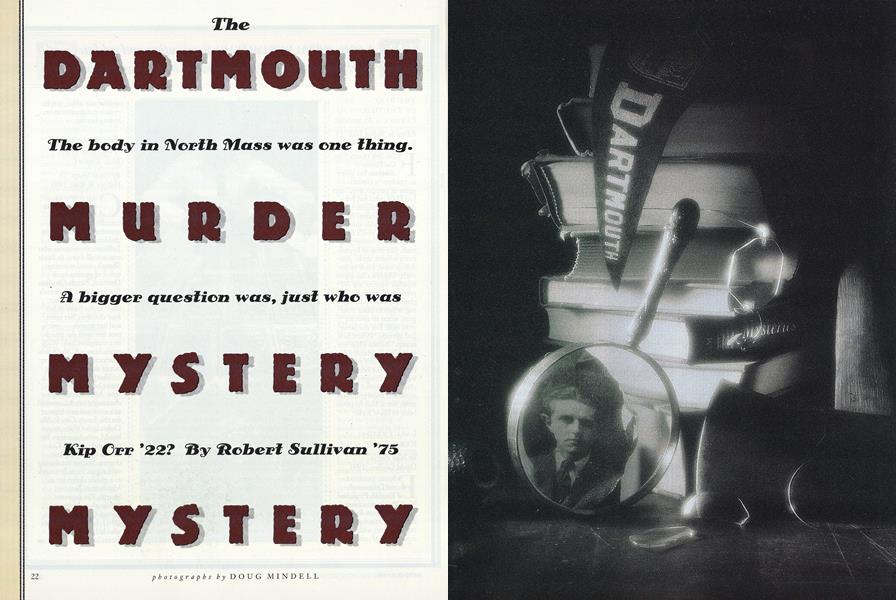

The body in North Mass Was One Thing A Bigger Question Was, Just Who Was Kip Orr '22?

Chapter One

THE THURBER CLUE

THURBER. JAMES THURBER. A mug's name Thurber. Ohio name. A mug from Ohio. But he was a sharpie, Thurber. I'll hand him that. The mug could write, and you know what that means. Means people read him. I did.

It was a hot day. I was sitting there. Thinking. Reading. Reading Thurber. Along comes this other name, Kip Orr. Snazzy name. A hepcat, I figure.

Seems Thurber knew this guy, Kip Orr. Knew him when they were working together in the Apple. The Apple. The Big One.

They were working together at The New Yorker, Thurber and Orr. Seems Orr used to write too. Seems he was in charge of the magazine's letters. Answered the mail. Thurber told a funny story about that: "A colonel, whom I shall call Comfort-Smothers, had written The New Yorker from his club in the city to say: 'Every time I pick up your magazine I fall asleep trying to read it.' Kip Orr answered that as follows: Colonel J.T. Comfort-SmothersThe Oldsters Club, New York City

Dear Colonel Comport-Smothers: Pleasant dreams."

PRETTY FUNNY. Funny guy. Kip Orr. I figured: A funny, odd Si wiseguy, with a funny, odd wiseguy's job.

Orr kept fish. He had a tank of fish in his office, said Thurber. He kept plants too. Orr did. Plants.

Orr went to Dartmouth.

Well, so did I. So you see, I was getting interested. I put my feet up, leaned back, and said "Hmmmmm." I woulda smoked a cigarette, if I smoked, or taken a slug, if I'da had one, or checked the chamber of my gun, if I owned a gun. But all I could do was go "Hmmmmm." And maybe raise an eyebrow, like they do in the movies, the mugs do.

And, said Thurber, Orr wrote a murder mystery. Yeah? So what? So'd Agatha Christie. Lots. About his college. Hmmmmm.

I'd never heard that. Never heard about a Dartmouth murder mystery. I thought and thought and thought, and came up blank. Which happens sometimes.

I took the case.

Chapter Two

I AM MY MOTHER'S SON

I TOOK THE CASE because, I gotta tell you: I am my mother's son. I guess the chapter tide told you that. Or maybe if you're a sharpie, you figured it out for yourself. But anyways, I am my mother's son.

She always had her nose in a Christie. Or a Sayers. A Gardner. Still does, my mother. Still has her nose in all that stuff. These days: Grimes, James. Christie too. Still. Always a Christie, with her nose in it.

Anyways, she'd leave 'em lying around, the books. I'd be snooping around, like I do, and I'd pick 'em up. I got hooked. It happens. It beat the hell out of Spencer, or some Sanborn House mug. Dangerous habit to have at test time but, what the hell.

So what am I saying? I'm a mystery buff. That's it. Nothing more. Nothing less.

So now I've got this Dartmouth murder mystery mystery, and it's bugging me. Who was this Kip Orr? What was this book? Who killed who? Why? When? Where? Did Bill inhale?

See—all these things were bugging me. Blame Thurber, that mug. I had the scent, and I couldn't shake it. Say, f'rinstance, this blonde, about ten feet tall and with legs that go all the way up, walks in. I don't even notice. I'm sitting there, thinking about Kip Orr and the Dartmouth murder mystery mystery. I'm a sap, I know. But that's the way it goes. Sometimes.

I took the case.

Chapter Three

PROSPECTING FOB KIP ORR

I'm IN HANOVER. First thing I learn, the mug's name's not Kip. Figures. I shoulda known. It's Clifford B. The card catalog tells me so. Baker card catalog. Baker. It's a library. You might've been there. Once.

Card catalog says something else. Says this book, TheDartmouth Murders, is kept under wraps. In the Treasure Room. Means you can't check it out. You gotta read it there, right in front of some snoopy librarian. So I'm thinking, I'll slip it under my coat and if anyone says boo, I'll pump two, three slugs into 'em. But, like I say, I don't own a gun. So I figure I'll read it there. In the Treasure Room.

I'm always looking for clues. So I ask the dame in the Treasure Room, "Hey, missy, other people read this book much?" She says something like, "'Missy?' What are you, a Neanderthal?" I say, yeah, I'm a Neanderthal. Used to be in Heorot. Whaddaboutit? She says, "Oh, I'm sorry. I understand.

"Well, yes, a surprising number of people read it. It's been out of print forever, and you can't find it in hardly any used bookstores. It had a local interest here, of course. And it's fun to compare Hanover then and now. The College then and now. And, of course, all those murders in the chapel, in the dorm. It's fun to think about that."

Fun? Murders are fun? She's a toughie, for a book-worm.

I take the book and go into a far corner, where I won't be watched. First I check out all the information in the front, to see what I can learn. I can read a book like a book. I'm a pro.

The book, called The Dartmouth Murders, came out in 1929. Farrar & Rinehart. Whole chunks of the story had been published earlier in College Humor magazine, which, I happened to know, was a hot sheet back then Dr. Seuss used to draw for it, and Corey Ford wrote for it, and, I guess, this Clifford B. Orr did too.

I started to read. Well, I'll tell you. It might've been in College Humor, but this was no funny story. It was funny like a slug from my .45, if I owned one. It was a murder mystery all right. This character, Professor Bossy Bostwick, says right up front, in the first chapter: "There's death in that wind." And I figured he was right. That chapter was titled "first Death," and to a pro like me that means two things: That someone's gonna die, and that the mug won't be the last. I can read a book like a book.

Christie always told my mom who was gonna be running around in a book, and I should do the same.

Here are the mugs: Ken Harris A senior. The narrator. Said he was at Psi U at 2 a.m. when...

Byron Coates...was killed in North Mass. Coates was Harris's roommate. He was a good singer. Before he got dead, that is.

Mr. Joseph Harris Ken's father. An alum. He always figured Byron was "moody—strange. Never liked him." Harris was a buttinski, a shamateur shamus with a weak spine: "Why, college men don't kill each other!" Wanna bet, Pops?

Charlie Penlon The downstairs classmate in North Mass. He slept in his clothes as Byron twisted in the breeze. He fessed up: "I must have had more drinks last night than I realized."

Prof. Bostwick "Blond bearded bachelor." Hmmmmm.

Sam Anderson "Big, slowgoing Scandinavian with a booming bass voice." Joined the choir. Big mistake.

Jean Coates—Byron's sister.

Vassar. You know the type. Ken did, too: "Quite good-looking in a dark, slim way, but a little strange." Up for the weekend and, Ken claimed, "was handed to me as a companion." Right.

THERE WERE OTHERS, but that's plenty for now. I never tell too much.

Chapter Four

WEAVING WEBS

THE THING ABOUT MYSTERIES IS, there are always plots behind the plots, plots inside of the plots, plots on top of the plots. Christie she'd weave this web, then she'd weave that one, and you'd get all confused and it would be, well, fan, I guess even though us tough guys hate words like fun. So I'm not gonna just go off and weave The Dartmouth Murders web. Orr did that already. I'm gonna weave the Orr web too, and maybe even the mother's-son web, plus bits of the Dartmouth Murders web. That oughta get us good and tangled, confused as all hell. Just like a mystery.

It seems Clifford Burrowes Orr was born during a blizzard on November 11, 1899, in Portland, Maine, which was then a two-horse town and is now lousy with college grads who don't own guns. He went to Portland High and was gonna go to Bowdoin but didn't. He went to Hanover in 1918, liked what he saw, showed his freshman mug on campus that fall.

You're saying about me: Boy, this guy's good. How's he know all this?

Yeah, well, none of your business. I don't wanna know how you do your job, and I'm a mug if I tell you my secrets. I was in a library. You can learn things there, sometimes, if you wanna. And I did. I didn't spend all my time in the Treasure Room, like a sap. No way, Giuseppe. I wandered around, looked here and there, found out things. I'm a pro.

I'll tell you one thing, 'cause I gotta so I won't get sued: A guy named John M. Clark '32 once talked to Orr at The New Yorker and spilled what Orr said right here in this magazine, years ago. I stole some stuff from Clark, and I'm fessing up right now. If anyone wants to make trouble over it, they can talk to my gun. They could. If I had one.

Anyways, Orr I'll tell ya what I learned about Orr. He comes to Dartmouth, does okay, gets involved. He was a creative mug, a Sanborn type. He wrote "Old Bottles," a column for The D. He was editor of the Bema, assistant editor of The Jacko, back when The Jacko was The Jacko, back when heavy hitters like Norman Maclean and Ted Geisel would kill time at The Jacko. Golden era.

He was musical, Orr was. He played piano, and wrote music for two Carnival shows, back when Carnival shows were Carnival shows. The shows were called Rise Please and Hush!, and they were done in 1921 and '22. Pretty funny, I guess. I saw photos. Guys dressed like dolls. Weird maybe. Funny too.

Orr blew town in '22, and this gets kinda screwy. His degree's with the class of '22, but he didn't get it till June, 1931. Apparently he was neck deep in "overcuts." But some of the obits called him "a brilliant undergrad." Go figure. Well, I knew guys in Heorot on the six-year plan, so...anyways, it's a mystery.

Orr went to Bean town and lived at 71 Mt. Vernon Street in an apartment. He worked the day shift at The Boston Evening Transcript. Wrote "Bookstall Gossip," another column. He wrote "humorous features" too. "My job is to write anything I darn please except when I am assigned things," he told a friend back then. "I have an article on Rheims in tomorrow's issue, and on the day the polo opens at Narragansett Pier, I have an article on the whole resort, gleaned from an expense-paid week-end there. The work is wonderfully interesting and just the kind of stuff I have always wanted. The hours are short, the pay good, the people the nicest in the world to work for, and the quarters excellent. What more could I ask for?"

Nice work if you can get it, pal. Anyways, Orr's in the catbird seat. He shoulda stayed there. But he didn't. He left, in 1925. He went to New York. The Apple. The Big One. A.K.A. Gomorrah.

He worked for McBride and Company, publishers. He was a publicity manager. Then he was an "editorial associate" at Double-day and Doran. What he really did: He ran one of their bookstores. That's a mug's game for a writer. He figured that way too. He free lanced. And he dreamed up this idea. What if a guy got murdered. Murdered in Hanover. What if?

A bookstore mug's got a lot of time to weave his webs. Orr wove.

Chapter Five

THE DARTMOUTHMURDER MYSTERY

BYRON COATES AND I were seniors together at Dartmouth, and roommates. We were roommates by chance as freshman and by choice the rest of the time. We were good companions, careless friends, and happy enemies when anything small enough arose to fight about. His claim to undergraduate fame lay in his really excellent baritone voice. Mine lay in a facility with the piano and an ability, after a fashion, to write dance tunes for the annual musical shows."

Orr wrote that. He wrote good, as you see. Good, but, I gotta say, in a melodramatic style. It-was-a-dark-and-stormy-night, that kinda stuff. Every chapter ended with a bang or a thud. That was because the murders were serialized. Orr he always left 'em hanging.

He left old Byron hanging, from a fourth-floor window. North Mass dorm. Byron was that "First Death." As soon as he turns up dead, old Mr. Harris starts his amateur detecting. He doesn't call in a pro, a pro like me. He goes off half-cocked. Big mistake. Meanwhile, Ken's all confused about Jean. "Gosh," he says, like a sap. "If she were only more human, I'm afraid I'd fall for her." Meanwhile, Charlie's acting mysterious. Hungover, too. Meanwhile, the College's president is all worried about bad press, about protecting "the name of the college as to undue and possible unmerited publicity an event which is bound to be a great obstacle in the progress of an eleemosynary institution as you expect Dartmouth to be." Typical.

Meanwhile, someone figures out Coates isn't dead by hanging, but from "a sharp instrument piercing the brain from under the back of the skull." Next, the president calls a meeting at Rollins Chapel and he's giving a speech to calm everyone down. But that doesn't work too good because old Sam Anderson comes tumbling out of the choir loft. He's dead, y'see. Murdered. Sharp instrument to the brain. This happens in the "Second Death" chapter. You might've guessed.

Mr. Harris is snooping 'round the choir loft later and sees someone who looks like Coates, who's supposed to be dead. There's a car chase with the ghost guy. It's like a Bruce Willis movie, except it's in New Hampshire: "We roared down the gully that the beginning of the Vale of Tempe forms. We roared up the hill over the flat past the golf links and the towering ski jumps. We barely missed a car turning in toward Hanover from the road that leads to the reservoir. We shot up steep hills, whirled around the corners, and dashed down again." No Chieftain on the Lyme Road back then, I guess. No D'Artagnan's.

Meanwhile... ...Nah, I'll tell ya more later.

Chapter Six

GOLDEN ORR

THE DARTMOUTH MURDERS, as I said, came out in 1929. Farrar really pumped it. "Clifford Orr writes well!" the posters said. "His characters are real, his plot is absorbing, original and ingenious." The dust jacket showed a dead kid in a dorm room, and Dartmouth Hall out the window.

The book was big. Orr became pretty famous. He quit the bookstore. He wrote a two-part mystery for College Humor called "The College Club Murders," and this was a hit too. But it never made a book.

Some of the obits say there was a movie made of The DartmouthMurders. Said it was called "A Shot in the Dark." This was news to me. I looked and looked, and nowhere could I find a clue. Nowhere, no-how. All the movie books talked about was that Peter Sellers thing, "A Shot in the Dark," from the sixties. But I saw that one once, and it had about as much to do with Dartmouth as boola-boola. If there was a movie, it's missing now. Disappeared. A mystery.

Orr, pretty famous, joined The New Yorker. He wrote a bunch of stuff for the magazine in the 1930s, a lot of "Talk of the Towns" and some longer stuff. The obits said he wrote a thing called "Savage Homecoming" that was "reprinted in several anthologies." But I don't know what that was about. A rough weekend against Harvard, maybe. Beats me. No one said, in the obits. And I couldn't find the thing itself. Another mystery.

Orr had a hit song. The same year The DartmouthMurders was big, so was "I May Be Wrong But I Think You're Wonderful," music by Milton Agar and Henry Sullivan, lyrics by Clifford B. Orr. A big hit, back then. Orr was flush. Orr was in clover.

And he was writing another mystery.

Chapter Seven

THE DARTMOUTHMURDERS REVISITED

KEN GOES TO BOSTON and meets Byron's mother and comes back and Charlie falls for Jean and Ken reads Byron's letters including "scattered feminine ones from Wellesley and Northampton" and there's a shadowy roadhouse in the "practically negligible village of Etna" named Sans Souci and at this joint they serve booze to studentslast Carnival a fraternity, probably Heorot, staged "a brilliant brawl" there—and the guy who runs Sans Souci has a son who looks a lot like dead old Byron and Mr. Harris becomes a suspect and he meanwhile learns what kinda gun shoots sharp objects into brains and Ken learns that the night Byron died Jean and Charlie and the guy that looks like Byron were all at the Sans Souci with "lots of liquor and pretty good music" and then there's another chase down Lyme Road to an old-fashioned inn where maybe some bad guys are and a shot rings out!

Chapter Eight

THE WAILINGROCK MURDERS

IN 1932 ORR'S SECOND BOOK, same title as this chapter, came out. It was big too, but not big big. Orr always figured it was the better book.

I took it out of Baker. Legit, I did this legit. It was in the stacks, so I didn't have to sneak it.

I read it. My mom read it, my friend Luci, a mystery buff too, read it. I wanted opinions from the pros about Orr, about if he was any good.

Wailing Rock was a rock that made a godawful wail when the wind blew on the Maine coast. Whenever the wail went, someone died. I gotta let Orr tell you about this wail: "Out of the night, filling the night came a tortured, shrieking cry. It was all about me, rising to an unearthly climax, wailing, dying again. It was the most awful sound." The book was gothic as all getout. Wuthering Heights on Route One.

There was a Sam Spade-type detective named Spider Meech. He wasn't as much of a pro as me, of course, but a helluva lot sharper than old Harris.

One clue I'll give ya is that Spider pulled a Roger-Ackroyd-type-of-deal in the book. Know what I mean?

Anyways, I got a kick out of the book. I consulted with my operatives, and they said they did too. Luci's testimony: "Orr was talented. He was overblown, maybe, but he could write."

And mom's: "It was well done, but pretty farfetched. The crazy mother, the butler almost did it, the double personalities. And the minute something happened, something else would happen. Also, by the end he was out of options. The ending had to be what it was. But overall, I enjoyed it. I loved Wells and Ogunquit. I could picture those places." Back in the thirties, readers liked it too. They bought it. Orr, still in clover, was able to take all kinds of time out of New York to see things, and to write. He went to New Orleans. The Big Easy. He loved it. Almost stayed. Didn't. Came back. Then he left Manhattan. Moved to Ithaca, of all places. That's a mystery. In fact, it almost was. Almost was a mystery. Y'see, he started writing The Cornell Murders.

That was supposed to be his third book. But, from what I can see, he never finished it.

Something happened.

Something happened there in the thirties and forties. Something mysterious.

Orr admitted to a friend that he was "getting lazy." He was back in New York now, back at The New Yorker. But he wasn't doing pieces that were getting in anthologies anymore. No way. And he wasn't writing any more hit songs. And he wasn't finishing that third book. Something happened.

Chapter Nine

THE DARTMOUTH MURDERSREVISITED AGAIN

THAT SHOT RINGS OUT, someone else dies "Third Death," you guessed it Coates, it turns out, might've had a half brother and Coates's mother might've known Ken's father way back when in Paris and Jean's hot for Charlie and Ken's jealous and there are three bullets found in the Inn, not two, and Bossy Bostwick's acting suspicious and...

Chapter Ten

A LIGHTBULB IN THE HEAD

I NEEDED TO FIND OUT MORE about Orr. I had feelings but they didn't amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world. I figured that Orr's hit song was probably a Tin Pan Alley type thing. But how could I be sure? I figured the guy for a wiseguy. But based on what? I figured he wasn't a happy guy. But I couldn't make it stick.

And something had happened. But what?

A lightbulb went on in my head. It was like a light-bulb going on in your head, you know? I thought: I'll call The New Yorker. I did. This guy named Chris said he'd go look, see if they had stuff on Clifford Burrowes Orr, 1899-1951. He said if they did, I could come over and look at it. Nice guy, Chris.

He came back and said all they had was the Times obit. He said that the New York Public Library was gonna open a New Yorker archive, and the magazine's old stuff was all in boxes. He said he was sorry. Probably was. Sorry.

Chapter Eleven

THE GILL CLUE

(Or: What Really Happened There,at The New Yorker?)

CALLING THE NEW YORKER made me think about The New Yorker. Things link up in my brain sometimes, like that.

I started thinking about Thurber again. I added some things up, and they didn't add up.

Okay, early on: a hit song, hit book. And later: a letter dated 4/28/45 where Orr tells a friend he hadn't "been doing much actual writing these past few years, being busy with desk puttering." Now, the obits mentioned a New Yorker masterpiece. But all Thurber said was that Orr answered the mail. What gives? Was he a writer or a go-fer? A man of letters or a writer of letters? And when had it happened? Whatever happened.

Hmmmmm.

The Thurber Clue. I made myself go back to the Thurber clue. Always go back to where you started. Christie taught me that. She taught me a few things: Look hard at the husband, follow the money, the butler might've done it and always, always go back to where you started. In this case, the Thurber clue.

If Thurber knew Orr, then that means.... Gill knew him too!

Gill. Brendan Gill. Fancy-dan New Yorker moniker, and a pen to match. If you couldn't find something in Thurber, you went to Gill.

Now, maybe too late, I did. I went to Gill.

Sure enough, in Here at The New Yorker, three references to Orr. The first: "a member of the staff named Kip Orr, who was armed with spite and feared nothing and nobody." The second: "gentle, venomous, red-eyed Kip." And the third....

Ah, the third. The third was a beauty. Three pages that began with the words, "Kip Orr, too, sought death, always more directly and recklessly."

I sat there at my desk. It was hot. The sweat on my neck seeped seepingly, drip drip dripping into my collar as I read, turning the pages slowly, soaking in Gill's deposition:

"He had been a brilliant undergraduate at Dartmouth and had written a successful mystery novel about the college. He sold a few casuals to us and a few pieces for the 'Travel' department...."

Okay okay okay. What about seeking death???

"Alcoholic and homosexual, Kip took terrible chances with his life, and it became a wonder that he wasn't murdered; more than once, he was rolled, beaten up, and left for dead in some dirty doorway in the Village, and yet he survived to die sadly in the small college town where, for a little while, he had known good fortune."

Jiminy Christmas! Why did I ever take this damn case? Why why why?

But I'm a pro. I read on: "When I first encountered him, he was perhaps in his early forties; his reddish pompadour was going gray and his large light-green eyes had lids shocking in their rolled-back redness. He had an air about him of ruined insouciance, and this was heightened by the fact that he wore good-looking, old-fashioned tweeds and English brogans with the exceptionally thick light-colored crepe soles that were in vogue in the twenties. Thanks to those soles, Kip was able to steal up behind one in the corridors and suddenly whisper some abrupt, catty remark, or the latest gossip about some fresh office disaster, and one was more startled by the fact of his presence at one's ear than by anything he said. He liked having things go wrong in the office; he wanted to see tables turned and to observe the discomfiture of people of importance.

"When the Shawns, then still childless, lived in a small apartment on Murray Hill, they gave pleasant evening parties, at which Shawn would sit playing, hour after hour, popular music and twenties jazz; his painted upright piano was rigged to give a true honkytonk sound. Orr would stand at one end of the piano, drink in hand, listening raptly. As the evening wore on, his eyes would grow more and more watery, and it was odd and touching to see him, as happy in those moments as he would ever be, apparently dissolved in tears....

"Alcoholics suffer from various consequences of their malnutrition; perhaps the most horrifying consequence is something called cortical atrophy. The cerebral cortex of the brain, giving us among other things our ability to reason, requires to be furnished with the richest possible blood, which the malnourished alcoholic is unable to provide; atrophy may then set in, with the result that the alcoholic becomes progressively less intelligent and more childlike. As the years passed, Orr began to bring toys of all sorts into the office, which he would occasionally take the trouble to demonstrate to me, kneeling on the floor and winding them up with evident pleasure. I was under the impression that he had bought the toys for some young niece or nephew, but not at all his mind was going and he had bought them for himself.

"One day I had undertaken to entertain a French journalist, who, making his first visit to New York, was eager to see the sort of bar frequented by his American counterparts. I led him to Bleeck's, on West Forty-first Street, next door to the New York Herald Tribune. Bleeck's was a favorite hangout not only of Herald Tribune employees but also of reporters on other newspapers, magazine writers, press agents, and theatre people. The Frenchman and I were standing at the bar, which was, as usual, extremely crowded. Suddenly, along the surface of the bar cluttered with beer glasses came a little toy automobile one of the first of those toys that by an ingenious mechanism was able, on reaching an obstruction of any kind, to retreat, change direction, and move forward again. The little car made its way along the bar, bumping into glasses, backing up, on occasion hovering at the edge of the bar and then correcting itself, and so continuously advancing, advancing. The Frenchman was beside himself with delight. So this was what an American newspaperman's bar was like! I let him suppose that it was, but I knew better. For at the far end of the bar I had caught sight of a tweedy arm, a trembling hand: poor Orr at play."

Chapter Twelve

THE END OF IT

I CLOSED THE BOOK ON ORR. I could've pressed farther, but what for? Let the mug rest. He was a wiseguy, sure, and I'm sure he was a booze hound. He lived a dangerous life. Okay. Some of us do. Some of us don't.

He wrote a big piece for The New Yorker once. I still don't know what it was about, but who cares. How many people write a big piece for The New Yorker?

He had that one moment in 1929 when his book came out. That moment, it was as shiny as the nickel on the barrel of my gun, if I owned one. Orr was a big guy that year, a guy with a big book. Someone made a movie out of it. Maybe. There are still loose ends. But it was a big thing, that's for sure. And how many people have even one big thing?

Also, he wrote a song that was a hit, back when mugs like Gershwin and Porter and Kern were writing hits. How many of us saps can say that? None of us, is how many.

He died young, 52, back in Hanover.

I know, I know. Orr, the poor mug it's a sad story, his story. Sure it is. But you know, it's...ahhhhh, the hell with it.

OH YEAH. That other story. The Dartmouth murder mystery mystery. Whodunit? Whaddya take me for, a mug? Mom wouldn'ta told ya. I'm her son.

Thurber said Orr wrotea murdermystery. About hiscollege. Hmmmm.

This wasno funnysotory. It wasfunny likea slug from

And hedreamed up this idea.What if aguy gotmurdered.Murdered in Hanover. What if?

The president calls ameeting atRollinsChapel andhe's giving aspeech tocalm everyone down.

Somethinghappenedthere in thethirties and.forties.Something mysterious.

I figured he wasn'ta happyguy. But Icouldn'tmake it stick.

I could've pressed further, but what for? Let the mug rest.

Robert Sullivan, a contributing editor to this magazine, is in Australia on an eight-month assignment withSports Illustrated. We don't know why.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

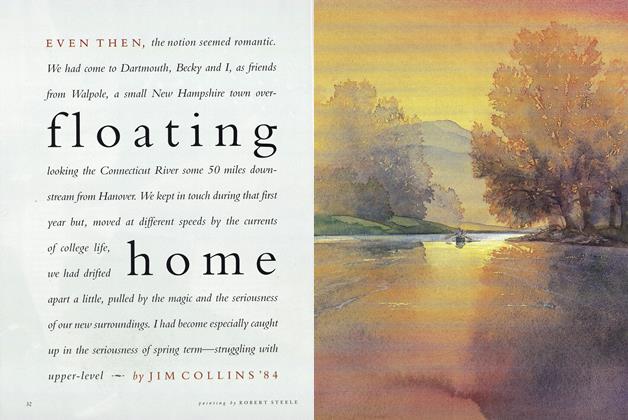

FeatureFloating Home

June 1992 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

FeatureLast Person Rural

June 1992 By Noel Perrin -

Feature

FeatureThe Woman Who Was Not All There

June 1992 By Paula Sharp '79 -

Feature

FeatureWhy in The World: Adventures in Geograhy

June 1992 By George J. Demko with Jerome Agel and Eugene Boe -

Feature

FeatureMurder on Wheels

June 1992 By Valerie Frankel '87 -

Feature

FeatureFenway: an Unexpurgated History of The Boston Red Sox

June 1992 By Peter Golenbock '67

Robert Sullivan '75

-

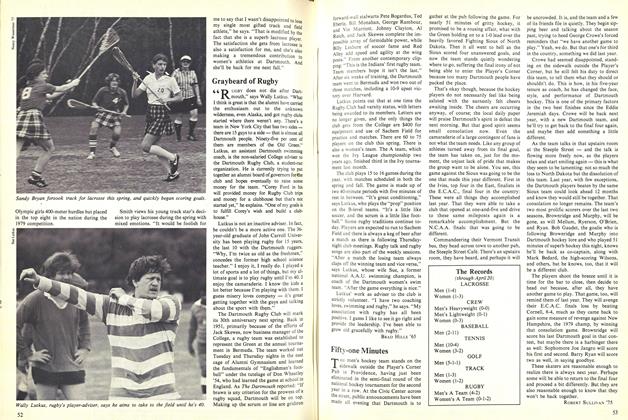

Sports

SportsFifty-one Minutes

May 1980 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIS HUMOR STILL POSSIBLE?

APRIL 1992 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

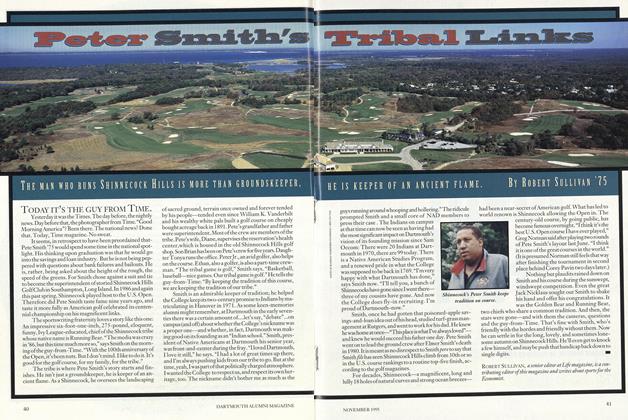

Feature

FeaturePeter Smith's Tribal Links

Novembr 1995 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

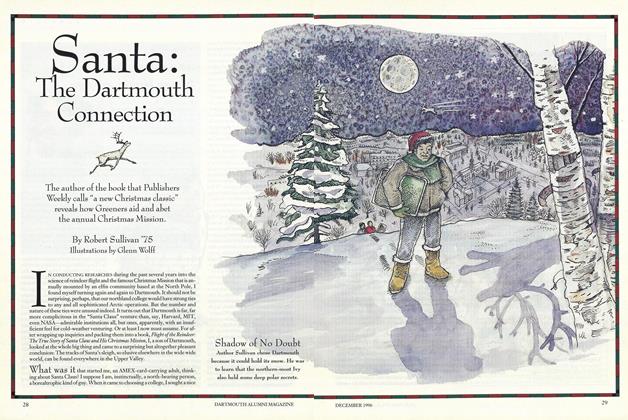

Cover Story

Cover StorySanta: The Dartmouth Connection

DECEMBER 1996 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureOld School New School

March 1998 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Article

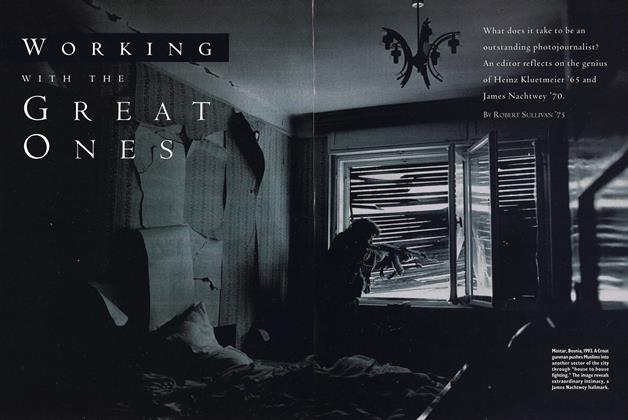

ArticleWorking with the Great Ones

JUNE 1999 By Robert Sullivan '75

Features

-

Feature

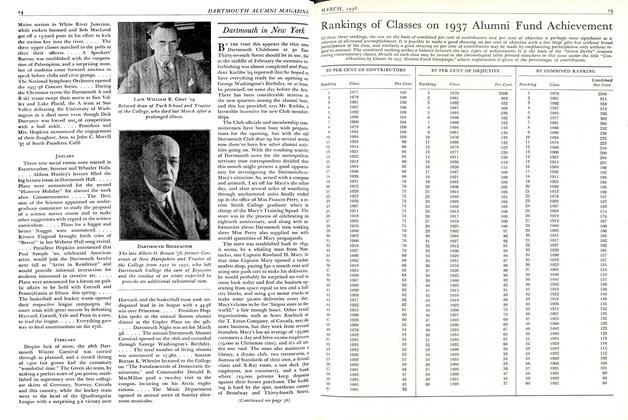

FeatureRankings of Classes on 1937 Alumni Fund Achievement

March 1938 -

Feature

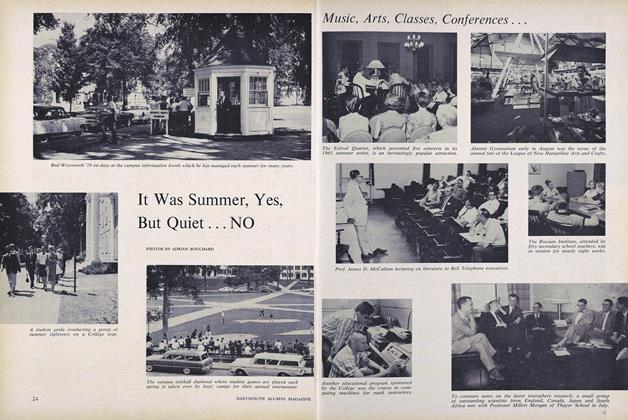

FeatureIt Was Summer, Yes, But Quiet... NO

October 1961 -

Feature

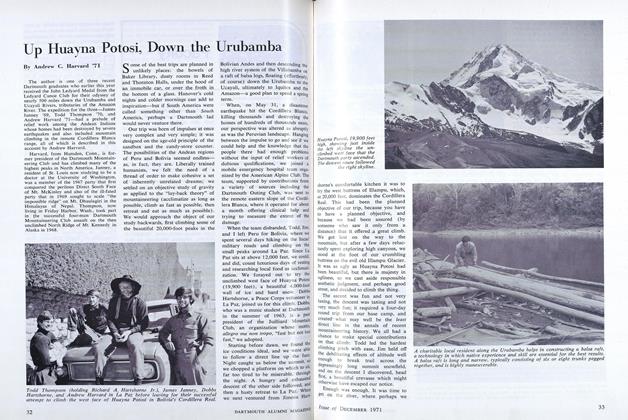

FeatureUp Huayna Potosi, Down the Urubamba

DECEMBER 1971 By Andrew C. Harvard '71 -

Feature

FeatureThe Computer Goes Fishing

September 1975 By DARREL MANSELL -

Feature

FeatureSenior Valedictory

JULY 1971 By DAVID M. LEVY '71