The United Nations has declared the nineties the "International Decade of Natural Hazards Reduction," and Stan Williams Ph.D. '83 is trying to do his part. One of "Stoiber's boys" a handful of leaders in geological research who all studied under Dick Stoiber '32 at Dartmouth-Williams addressed the National Press Club on May 5 as an expert in volcanology, the study of volcanoes, and as the leader of a UN and National Science Foundation-sponsored expedition to Galeras Volcano in Columbia. But he also spoke as a first-hand witness to the destructive power of volcanoes.

The Galeras expedition took place in January 1993, and 40 scientists from 14 countries were in attendance. On the fourth day, January 14, Williams led a group of 15 into the summit crater to gather gas samples and geophysical data. At the end of the day, as a few scientists still lingered, the volcano erupted. There was no warning. Five scientists who were working in and around the crater were killed instantly. Williams, who was on the rim, tried to run but was hit by airborne incandescent rocks. His skull was fractured, both legs were broken, and he caught fire. Another scientist and three tourists nearby were killed. Williams rolled to put out the flames; an hour later he was rescued by his Colombian Ph.D. student, Marta Lucia Calvache, and an American woman. Flown by helicopter to a hospital in nearby Pasto, Williams immediately underwent brain surgery. Recently he had a chunk of his skull removed from one area to patch the hole, and shattered bone fragments were removed from his leg. He wears a device that will stretch his bones back to their proper length over the next few months.

"This event has caused some of the scientists on the scene to be so stressed that they are unlikely to do any more work there," says Williams. "It only makes me more determined to try new approaches, like instrumentation, to forecast eruptions." Much of Williams's work has focused on determining what sort of changes in volcanic gas emissions might signify an impending eruption. He and colleagues are developing inexpensive, lightweight, real-time monitors that will relay information from volcanic craters to safely removed scientists. Costing less than $5,000, the devices will be expendable and more accessible to scientists in developing countries than the expensive remote-sensing equipment currently in use.

Stoiber and Williams in Japan.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

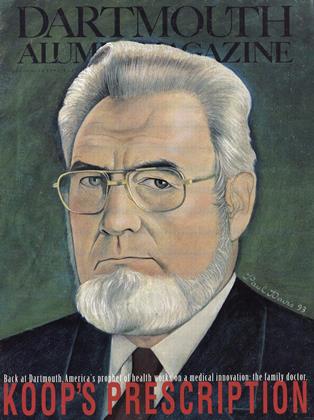

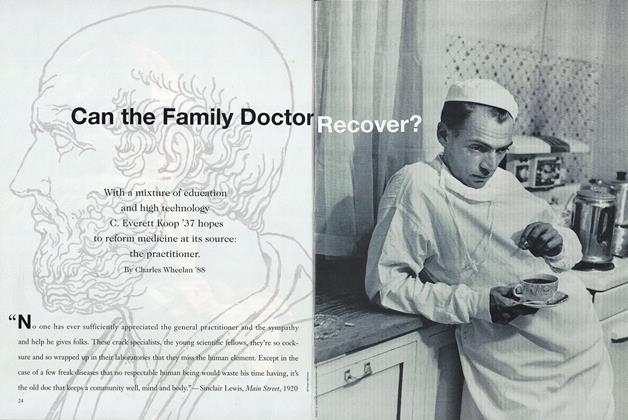

Cover StoryCan the Family Doctor Recover?

November 1993 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureTHE OLD MEN AND KC

November 1993 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Feature

FeatureProphet of Limits

November 1993 By Suzanne Spencer '93 -

Feature

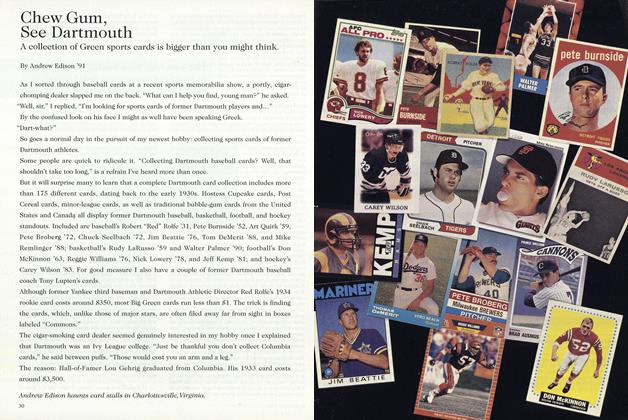

FeatureChew Gum, See Dartmouth

November 1993 By Andrew Edison '91 -

Article

ArticleDivers Notes & Observations

November 1993 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

November 1993 By William Blake, W. Blake Winchell

Heather Killebrew '89

-

Feature

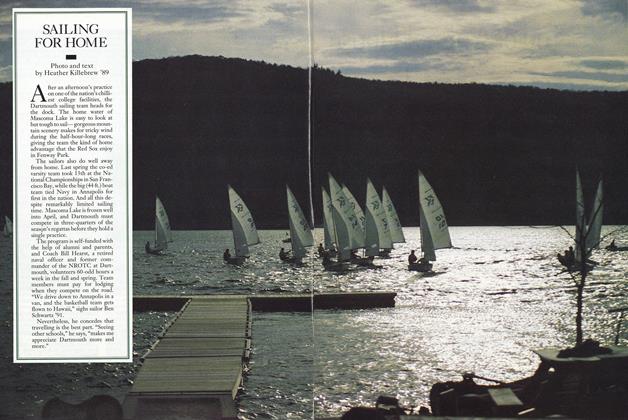

FeatureSAILING FOR HOME

SEPTEMBER 1989 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Article

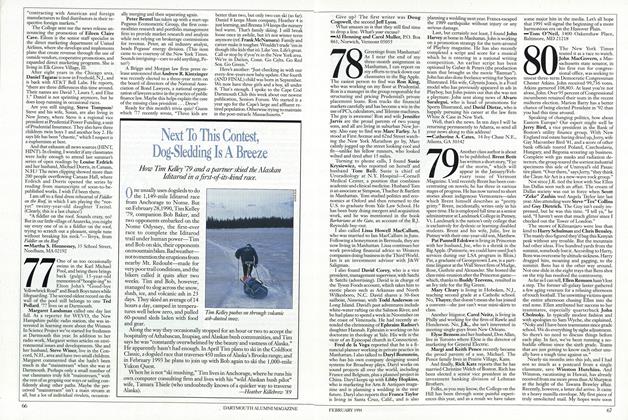

ArticleNext To This Contest, Dog-Sledding Is A Breeze

FEBRUARY 1991 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Article

ArticleTalk About Suspense

FEBRUARY 1994 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Article

ArticleKunar, Afghanistan, 1986

December 1994 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Article

ArticleOnce Upon a Time

NOVEMBER 1996 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Feature

FeatureKnowing Squat About the Woods

MARCH 1997 By Heather Killebrew '89