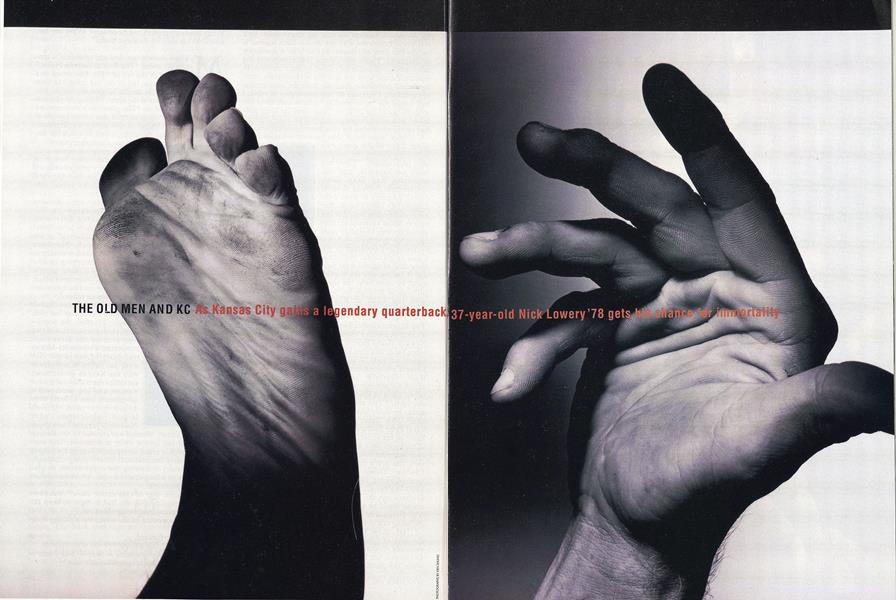

Kansas City quarterback 37-year-old Nick Lowery '78 gets his chance for immortallty

Hey, Joe," says Nick Lowery '78, sauntering over to his newest teammate. "I just wanted you to know that there are at least two 37-year-olds on this team who can still play."

"The grunts and groans are audible on the Astro Turf of the Kansas City Chiefs' indoor training facility as the entire team prepares for the first ritual of mini camp. In a few moments everyone will undergo a gauntlet of physical tests—sprints, long jumps, vertical leaps, powerlifts, and agility drills to make sure their bodies are in proper working order for the upcoming season.

Everyone, that is, except the quarterbacks and the kickers, whose elite talents can't be quantified in quite the same way as a receiver's speed or a lineman's thrust. While `the masses stretch, toil, and grunt, the Chiefs' three quarterbacks, punter, and placekicker look over with casual interest at the rest of the team.

Kickers and quarterbacks aren't very popular among their teammates at moments like these. But this time, the toiling masses are sneaking curious peeks in the direction of this crowd, at one quarterback in particular. This is their first glimpse at a man who by an improbable set of circumstances—seems to have stepped out of an NFL's Greatest Moments video and into a Chiefs uniform. Joe Montana has earned his place in immortality. The question now is whether a patched-up throwing arm will let him continue to act immortal. The man beside him, placekicker Nick Lowery, has had his share of great moments, but he is not yet the greatest of all time. For one thing, he has never been to a Super I Bowl. Montana may be the last and best chance for the 37-year-old Lowery to kick his way into a championship.

It was a momentous occasion for Montana to be a Kansas City Chief, the man who owns more Super Bowl rings all by himself (four) than the rest of his new teammates put together. The NFL's Most Valuable Player just three seasons ago had undergone surgery on a tendon in his throwing arm in 1991, quarterbacked only a single half of football in '92, and the 49ers faced with an embarrassment of riches at quarterback in the bodies of Steve Young and Steve Bono authorized and encouraged Montana to shop his talents around the league, hi the end, San Francisco had to make the tough choice: to say goodbye to yesterday (and those four Super Bowl victories) and let go their certain Hall of Famer and perhaps the most proficient quarterback who has ever played the game.

Here at the first mini-camp of the 1993 season, the curious glimpses reflect what all the Chiefs are thinking as they watch this man at his leisure and look toward the next months of football: If he can still do what he could do just a couple of years ago...if our offense can score just a few more points...ifwe can ratchet this team up one more notch...

"I love this job," chuckles Joe Montana to quarterback Dave Krieg, rookie Matt Blundin (who threw an NCAArecord zero interceptions at Virginia in 1992), punter Bryan Barker, and Lowery. Just the day before, The Kansas City Star had run a column under the headline, "Say No to Joe." The article postulated that if the San Francisco 49ers didn't want a 37-year-old, post-surgery Joe Montana, then the Chiefs shouldn't either. And it was with that article in mind that Lowery, who'd met Montana before but never really talked to him, offered words of welcome.

Montana replied that he appreciated the thought and asked when Nick wanted him to hold the football for him.

"Whenever you feel like it," said Nick. (A friendly response, by the way, considering that Nick, who last season hit 21 field goals in a row with Barker as his holder, stuck with the status quo to good effect: through the first six games he's made ten of 13 field-goal.tries, including five in a 17-7 win over Denver on "Monday Night Football" and a 37-yard game-winner in a 17-15 victory over Dave Shul '81's Cincinnati Bengals.)

After the practice, Lowery and Albert Lewis, a Pro Bowl cornerback, took Joe out to dinner, told him about the team, and talked about the season to come. "He's on a mission," says Lowery. To Montana, there is only one destination: die Super Bowl. Being told that he was too old to lead a team there simply made it more inviting. Montana had an offer for lots more money from the Phoenix Cardinals, but he elected to go with the Chiefs. The difference was that Phoenix is years away from the Super Bowl, and Kansas City is young, ascending, and on the verge of greatness. A playoff team in each of the last three seasons, the Chiefs made it to the first round in 1990 (they lost 17-16 to Miami when Lowery's 52-yard field-goal attempt fell a yard short), to the divisional playoff game in '91 (they lost to Buffalo 37-14), and to the first round last year, where they lost to San Diego, 17 to nothing.

One of the biggest problems was that the offense simply did not score enough, averaging about ten points a game in playoffs over the past few years, and the offensive line was breaking down toward the end of those games. Head coach Marty Schottenheimer has been a football conservative who used the offense as a way to set up the defense running the offense behind 6'1", 260-pound Christian Okoye, trying not to make mistakes, and hoping to get few breaks on defense. This is not the way to win championships in a league filled with teams that can score 55 points in a single half (as Buffalo did last year). So Schottenheimer hired as offensive coordinator Paul Hackett, who had learned his offensive schemes under the sultan of aerial philosophy, Bill Walsh, in San Francisco. When Hackett installed the San Francisco system, the players were ecstatic: The system makes sense; the blocking schemes are simpler; and the players understand it. And now to run the system there is Joe Montana, who probably understands it better than Hackett does.

There is no Jerry Rice here for Montana to throw to. But soon after Montana came another possessor of Super Bowl hardware, Marcus Allen, formerly of the Raiders, who even at 33 is one of the most reliable, versatile runningbacks in the league.

"There's no question," says Lowery. "This is our best chance for the Super Bowl. Before, the door to that room was ajar. Now we're in that room, and we have to think in more specific, realistic terms about what we have to do to win the championship."

For Lowery, this has been a long time coming. His excellence at his position can be measured by any number of numbers. Over his 15-year career, Lowery has made 80..2 percent of his field-goal attempts. Only Pete Stoyanovich of the Miami Dolphins (at 79.9 percent) is even close. And Lowery keeps improving. He has missed just 13 of 104 field-goal tries in the nineties (that's a success rate of 87.5 percent). He has kicked more field goals over 50 yards than anyone in history. And at the start of this season, Lowery had kicked a total of 306 field goals. In NFL annals only Jan Stenerud and George Blanda have more, with 373 and 335, respectively. In three seasons, Lowery could surpass those totals.

And then there are Lowery's contributions off the field. His Kick with Nick program, which has raised some $600,000 for United Cerebral Palsy, is the longest-running program of its kind. As chairman and founder of Kansas City's Area Role Models for Youth (A.R.M.Y.), Nick has united all the city's pro sports athletes in an ongoing anti-drug mentoring program. He has also been a fulltime volunteer with the White House Drug Abuse Policy Office. "What I'm doing means everything to me," said Lowery in a June article in Sports illustrated that described his work in the White House Office of National Service (with Rick Allen '75) and pictured him chatting with Bill Clinton.

There's also a fact about life in the NFL: all of it counts for very little without the digital hardware. With all those numbers and all those good deeds, Nick is still kicking in the shadow of Jan Stenerud, whom he beat out for a job in 1980. Stenerud won a Super Bowl. The Kansas City fans love the current Chiefs every game is a sellout. But the real celebrities around town are still the members of that 1969 team that beat Minnesota in Super Bowl IV.

the oldest member of the Chiefs by two weeks. (His birthday is May 27, 1956; Montana's is June 11.) Lowery is also the fourth oldest in the NFL, behind Steve DeBerg of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, Jackie Slater of the Rams, and Phil Simms of the Giants. With all the talk about Montana's age, Lowery is still

Last February, Lowery gave the American Football Conference a 23-20 victory in the Pro Bowl with a 33-yard field goal in overtime. He is already a certain Hall of Famer. It is well within his grasp to play the next three to five years and end his career as the indisputable number-one kicker who ever played the game.

But the fact is that this is the year everyone will or won't—hear of Nick Lowery. His chance for immortality, to borrow from George Allen, is now. "Walter Payton waited ten years to be part of a great team," says Lowery. "I'm no Walter Payton, but this team can be a great team. Everybody's talking about the Chiefs now. We're a respected organization."

And Montana? "The only difference between the way he throws the ball now and the way he threw the ball five years ago," says Nick, "is that he has a scar and a little bit of calcium built up under the skin of his right elbow. If you look at it, the point of the elbow looks a little bit larger.

"He's incredibly down-to-earth. He plays within himself. He's more at peace with himself than any player I've ever seen."

Montana's specialty is the ten- or 20-yard pass, timed perfectly, delivered directly on target. "Joe is so much more accurate than other quarterbacks," says Lowery. "Joe hits the receiver exactly in stride. The receiver doesn't have to stretch. He doesn't have to bend over. He doesn't have to reach up. The pass is always right there."

And what of Lowery's talents? Comparing himself to the other kickers, Lowery says that Morten Andersen (of the Saints) and Chip Lohmiller (of the Redskins) have the strongest legs in the league. Stoyanovich, he says, "has very good balance. A good smooth swing. He's very strong mentally. He's a good athlete. He has good follow-through." And how does he kick compared to five years ago? "I'm more consistent," he says. "I could probably hit a 65-yarder more readily when I was 25." He had only one attempt over 50 yards last year; he made it by ten yards. Still, he says, it would be a challenge to hit one that long today. "It would be real difficult."

Lowery is also training better these days than a few years ago. "I'm focusing on power," he says, "not endurance. I do the Stairmaster for 20 minutes. I work on intensity and intervals. I also run with Power Pants [made of Neoprene, with spaces in the pockets for lead weights] to build the hip flexor and butt." That's along with the regular team training—squats and lunges, speed squats. And there's an Eagle four-way leg machine, which builds up the hip, flexor, hamstrings, and groin.

"I hope to play a minimum of three more quality years," he says. "With a little luck, at least five." And after that will come a beginning, not an end. Starting with his government degree from Dartmouth in 1978, Lowery has clearly been thinking about life after football. Not long after his graduation from Dartmouthand before two years of unsuccessful tryouts for 11 different NFL teams Lowery was back in his hometown, Washington, D.C., working as an aide to Rhode Island Senator John Chafee. One day, Lowery ran into Bill Bradley and introduced himself, asking for advice as an athlete who wanted someday to get into politics. "He told me, 'Get as many experiences as you can, in all facets of life. Do everything.'"

In all those offseasons of work in Washington, Lowery has put himself in a great position to launch a political career and perhaps become the second member of the class of '78 in Congress (after Rob Portman, a Republican who was elected to Congress from Cincinnati this May). But Lowery feels strongly that this is not an end in itself but a byproduct of the work he's been doing all these years. "It's not worth it to be a politician just to be a politician," he says. "You have to have a foundation of business success and from that, choose an opportunity."

On that last remark, consider this: The last play of the last game of Nick Lowery's high school career was a 43-yard field goal into a November crosswind with no time remaining to lift St. Albans to a 9-6 victory over its archrival, Landon. At Dartmouth, Nick kicked game winners over Holy Cross and Yale. When he has had a chance to give the Chiefs either a win or a tie in the last two minutes of a regular-season game, he has converted ten of 13 times. He persevered through 11 rejections from eight NFL teams, has polished himself into a kicker without peer, and established himself as the NFL's best citizen.

Something should tell us that Nick Lowery will find an opportunity.

All of it counts for very little without the digital hardware.

This is the year everyone will or won't hear of Nick Lowery.

A former writer-reporter with Sports Illustrated, Brooks Clark is afreelance writer and editor in knoxville. He is the secretary and newslettereditor of the class of 1978. And he will soon know what it's like to be 37.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

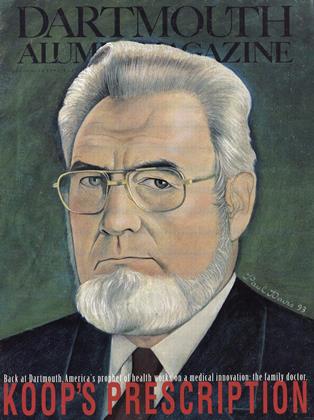

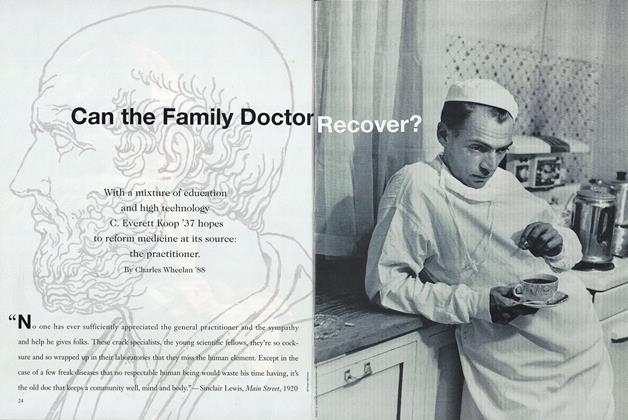

Cover StoryCan the Family Doctor Recover?

November 1993 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureProphet of Limits

November 1993 By Suzanne Spencer '93 -

Feature

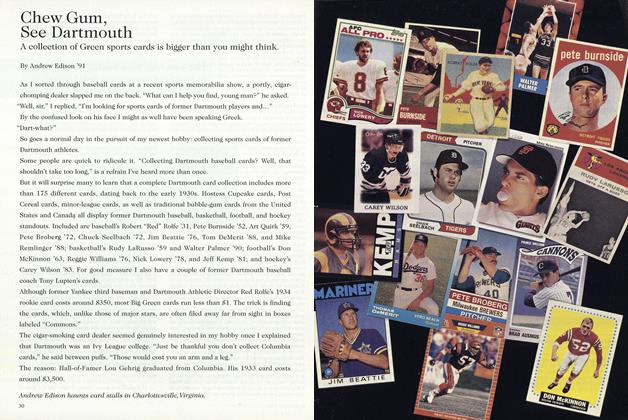

FeatureChew Gum, See Dartmouth

November 1993 By Andrew Edison '91 -

Article

ArticleDivers Notes & Observations

November 1993 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

November 1993 By William Blake, W. Blake Winchell -

Article

ArticleAdvancing the Human Condition

November 1993 By James O. Freedman

Brooks Clark '78

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

Nov/Dec 2005 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

Sept/Oct 2008 -

Article

ArticleThe Jump to Gotham

December 1994 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPease Out There

MARCH 1995 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPoetry From the Heart

MARCH 1995 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Article

ArticleMelissa McBean, Scoring Machine

October 1995 By Brooks Clark '78