With a colond marker, Adjunct Professor of Environmental Studies Donella H. Meadows fills in a graph showing two trends: Between 1972 and 1989 the world's population jumped from 3.6 to 5 billion, and the rate of fossil-fuel consumption grew by 40 percent. Dozens of lines and bars show population Growth, industrial production, carbon-dixoxide emissions, and availability of food and other resources, all data taken from Meadows's book Beyond the Limits. (The Economist would later sniff of her graphs, "It beats drawing straight lines, but not by much.") While her marker squeaks softly, she talks to her Environmental Studies 73 seminar about "overshoots" population growth and resource depletion in a finite world.

A male student asks why there were no dips in population during world wars. "Men are expendable," Meadows replies, explaining that, from the standpoint of population dynamics, humans are no different than sheep. You can kill most of the males in a population, but, as long as numbers of females remain stable, the population as a whole can keep growing.

Donella Meadows (her friends and students call her "Dana") is one of those rare scientists who are seeking to cross-pollinate two ordinarily hostile species: research and journalism. The experiment has not gone entirely smoothly. In attempting to portray the complexities of the earth's resources, Meadows has found it extremely difficult to publicize her research while keeping it undistorted.

A Dartmouth biophysicist and sheep farmer, Meadows first garnered national attention when she co-authored Limits toGrowth, a study of the effects of population and economic growth on the world. The study used a computer method called systems dynamics. Pioneered by MIT researcher Jay Forrester in 1970, the method allows researchers to analyze a variety of complex systems from the human body to the national economy to global resources. Limits contains no predictions or prophecies, but allows the reader to choose from among 12 different "futures." The most optimistic future one that the model estimates would come from proper conservation—has an earth population of eight billion people living indefinitely at the European standard of living. Hints at starker futures are being given by the planet itself; Meadows says that global warming, forest die-offs, desertification, and species extinctions are signals that if we do not set our own limits, the earth will. The findings of Limits were meant originally for scientists who made up an exclusive group called the Club of Rome, but the organization asked her to explain them to the public. The book sold nine million copies in 30 languages.

Meadows was not entirely pleased with the results. Limits was banned in the U.S.S.R. and investigated by the Nixon White House; worst of all, she says, the book was "close to 100-percent misreported." A projection never mentioned in the book that the world would run out of fossil fuel by the 1990s appeared in one newspaper story and was repeatedly picked up by other reporters. "The media people were reading the media, not the book," she maintains. "They were not thoughtful about the fact that they were trapped in their culture, a culture that believes that there are no limits to growth."

Her only chance to explain her book live came during a three-minute "Today" show appearance in 1972. Her explanation of systems dynamics was sandwiched between a mouthwash commercial and a British dart-throwing demonstration.

Clearly, books and talk shows were not enough. In 1985 Meadows quit her fulltime Dartmouth teaching job and began writing a newspaper column called "The Global Citizen." Now syndicated in 20 newspapers and covering topics as widely dispersed as nuclear waste and Ben and Jerry's ice cream, the column consistently hammers home one basic message: If we continue to treat the earth as an expendable resource it is the human population, not the earth, that will perish.

Meadows continues to teach one course a year, a seminar in environmental journalism that gets students to write for mass-market publications. I took that course, and it was anything but comfortable. For our first class, Dana handed out a draft of an op-ed piece she was planning to publish in her column. She told us to tear it apart. We looked around the room in shock. This was the first time a professor ever demanded constructive criticism of a draft, let alone finished copy, of her own work.

But we gave it. In her column she condemned a group of scientists for planning to collect the DNA of vanishing indigenous tribes without any apparent concern for the living people. After an awkward silence, we began marking paragraphs for monotony and redundancy. Finally one student, seeing that Dana's anger went in circles, demanded, "What's your point?"

Between that class period and her deadline, she made a clear and eloquent one.

In another class, she directed us in a computerized deep-sea-fishing simulation. After a series of boat auctions, fishing seasons, fish-population declines, and failed fishing-limit negotiations, our supposedly ecocorrect class ended up raping the deep sea. Worldwide fish populations plummeted in a pattern remarkably consistent with reality. Our teams, representing smalltime fishers and big industry, bickered in ways that would have been familiar to people in the business.

As an added slap in the face, the course insists on a real-world experience with the media. Each student is required to write and market an article for a newspaper or magazine. I sent out a piece that contrasted the much-publicized pollution caused by state socialism in Eastern Europe with the new but no-less-severe environmental destruction resulting from the introduction of capitalism. I received 40 rejection letters in reply; I had missed the "news window," editors said. Only five students out of the 20 in our class ended up being published in a non-campus paper; two of these students had previously written for commercial publications.

A more bitter lesson than personal rejection is the sense I got of the quality of reporting among the media's own professionals. "There has been no hysteria, and the reporting has been more responsible," Dana said of recent coverage of Beyond theLimits, her sequel book. But environmentalists note that her recent book received attacks similar to ones leveled 20 years ago at her first book when it received any coverage at all. Calls to national reporters show that Meadows is no pundit. "I am not sure she is influential by name only, but she is influ-ential through her work with the Club of Rome," says David Shribman '76, Washington bureau chief of The Boston Globe. Environmental reporters from U.S. News & World Report, on the other hand, said they had never heard of her. Wall Street Journal environmental writer Rose Gutfeld says that Meadows' message was "much talked about at Rio." However, she adds, "The average lawmaker probably hasn't heard of her." USA Today Editor-in-Chief Peter Prichard '66 hadn't Manheard of her either; Meadows's name has not appeared in the paper since its founding in 1982. "We publish an environmental columnist in USA Weekend," Prichard says. "He gets a decent reaction, but nothing like Ann Landers." Though Meadows's columns have been recognized with a 1991 Pulitzer Prize nomination and a 1990 Walter C. Paine Science Education Award, Prichard says the best way for her to get her message across would be to follow the path of Carl Sagan and Alan Dershowitz and use the media more aggressively, including talk shows, to popularize her opinion.

"Of course I don't feel successful in getting the message of Limits out to any audience," Meadows responds. "I don't expect everyone to agree with our assessment, but I will think the work of Limits is done when the public media and policymakers begin to address its questions. What, truthfully, is progress? What kinds of growth are necessary? What are our limits? What shall we do about them?"

Meadows showed our class one episode of a tenpart PBS series, "The Race to Save the Planet," first aired in the fall of 1991. She served as a consultant on the series, but in the end refused to have her name printed in the credits because she felt the title contradicted the point of the series. "Saving the planet is not a race," she told us. "The planet isn't in danger, we are, and it is pure hubris to think that we are capable of saving a planet." Meadows is now writing a college textbook to accompany the series, a task in which she has been given complete control.

The program opens with Meryl Streep sitting on a deck overlooking a pristine country lake. "Can we fast-forward this?" Meadows asked. We wouldn't let her.

Likewise, when Robert Redford appeared on the screen drinking beer with other movie stars at an environmental "gathering" at his Colorado ranch, Meadows groaned and asked us to skip it, muttering something in disgust about watching people congratulate themselves about their work on the environment. Again we refused.

The program concluded not with a movie star but with Wangari Maathai, the prominent environmental activist who created the Greenbelt movement, a successful African tree-planting campaign. Her work has fallen into disfavor with the Kenyan government; she defies the traditional role of women, and she prevented a government plan to build what would have been Africa's largest skyscraper over Nairobi's largest municipal park. Last January Maathai was arrested by the Kenyan government and beaten while in detention. This incident, reported in major newspapers, became the subject of an Amnesty International letter-writing campaign. Maathai's story is forcing the organization to give recognition to a long-ignored topic: environmentalists as political prisoners.

"She is the star of this entire show," Meadows announced, noting that she had to fight to keep the Maathai interview from being edited out.

Streep reappeared on the screen for a closing statement.

We hit fast-forward.

"There has been no husteria, and the reporting has been more responsible." Dana said of recent coverage of Beyond the Limits.

A male student asks why there were no dips in population during world wars. "Men are expendable." Meadows replies.

Suzanne Spencer graduated in Summer with honors inhistory and a certificate in environmental studies.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryCan the Family Doctor Recover?

November 1993 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureTHE OLD MEN AND KC

November 1993 By Brooks Clark '78 -

Feature

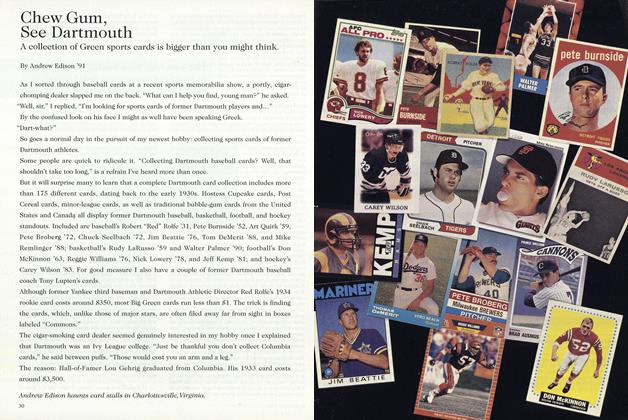

FeatureChew Gum, See Dartmouth

November 1993 By Andrew Edison '91 -

Article

ArticleDivers Notes & Observations

November 1993 By "E. Wheelock" -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

November 1993 By William Blake, W. Blake Winchell -

Article

ArticleAdvancing the Human Condition

November 1993 By James O. Freedman

Suzanne Spencer '93

Features

-

Feature

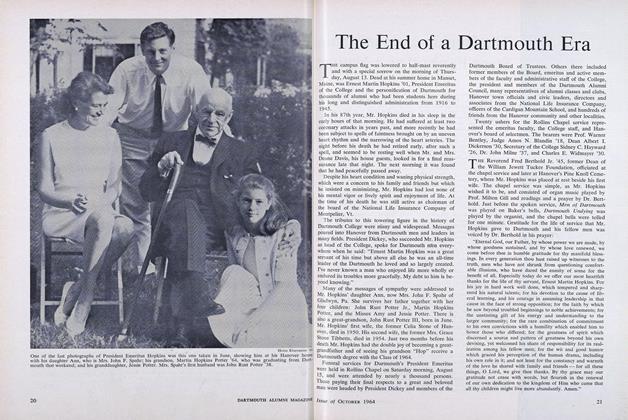

FeatureThe End of a Dartmouth Era

OCTOBER 1964 -

Feature

Feature40 Years at the Helm

OCTOBER, 1908 By Charlie Widmayer '30 -

Feature

FeatureHe Knew what Played

MARCH 1988 By FRANK D. GILROY '50 -

Feature

FeatureHistorical Notes on the Upper Valley

APRIL • 1985 By Jerold Wikoff -

Feature

FeatureThis Man Is an Island

OCTOBER 1996 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to the College

JULY 1967 By STEVE GUCH JR. '67