MOST AMERICANS agree that our schools are in trouble. Yet, oddly enough, the story of what has happened to the American education system in the second half of the twentieth century is not one of failure and decline but of perverted success. The United States is the victim of the enormous success of its own nineteenth-century educational system, history's most revolutionary, most productive experiment in schooling.

In the mid-nineteenth century Horace Mann, secretary of state for Massachusetts, devised the notion of free, universal, compulsory elementary education for all. He argued that education produces good character and a sense of civic responsibility; most importantly, he said, education was a good investment, "the most prolific parent of material riches." Educated workers produced more, earned more money, paid more taxes, bought more goods, and generally contributed more to the economic good of all. Mann saw education as a democratic social sorting mechanism: the best students could go to high school and college and transcend the limits of their birth, while others would be prepared as punctual, industrious, and docile workers well-suited to the exigencies of nineteenth- century production. Schools developed to carry out these functions were deliberately patterned after "modern" assembly-line factories. As late as the 1930s, Elwood Cubberley, a leading authority on educational policy, was saying proudly that schools are "factories in which the raw materials are to be shaped and fashioned into products to meet the various demands of life....This demands good tools, specialized machinery, continuous measurements of production to see if it is according to specifications, the elimination of waste in manufacture."

From the standpoint of educational productivity, the system worked brilliantly. By 1950 illiteracy had sunk to three percent of the population and the proportion of high school graduates had risen from six to 59 percent. According to plan, people who weren't served by the schools at different levels moved out into a job market expanding in opportunity for semi-skilled labor.

So what happened? The system still works the same, but the world didn't stay put. As communications and transport became more efficient worldwide, manufacturing came into direct competition with the developing world, and American heavy-labor and assembly-line industry declined precipitously. Demand for the "waste products" of schooling dried up.

If America is to compete in this new economic system, it must replace "high-volume" with "highvalue" production. As the new secretary of labor, Robert Reich '68, points out, to make this shift we need graduates who can think critically; read and write with meaning; understand the concepts, not just the formulas, behind mathematics; find and use both abstract and concrete information; set and solve problems that have multiple answers; experiment and learn from errors; and work collaboratively with others. So far, most of our nation's schools and educational reform efforts have failed to produce such people.

Former Dartmouth Education Professor Theodore Mitchell, now dean of the UCLA School of Education, divides school reform into three categories: toying—moving the blocks around; tinkering fiddling at the margins; and transforming—asking, "What do our young people need to know and be able to do to live and work productively in the foreseeable future?" and then working to create a school system designed to achieve those goals.

Most of what has happened in this country since Horace Mann is either toying or tinkering. We are toying when we say that if our 17-year-olds do not know how to do math, we should require them by law to do more of the stuff that hasn't taught it to them, spreading an ineffectual curriculum over three years instead of two. An example of tinkering is the proposed National Examination System, which seeks to expand, standardize, and enforce the same high school curriculum we have known since the 1890s.

Unlike previous efforts at major educational change—the GI bill, for example, or Head Start—what is needed now can't be added onto or operated outside the established system. The kinds of learning that we must address do not fit into the typical school schedule, curriculum, or teacher deployment that places teachers in isolated classrooms teaching isolated subjects. Real transformation requires fundamental changes in the way we structure schools and conceptualize teaching and learning.

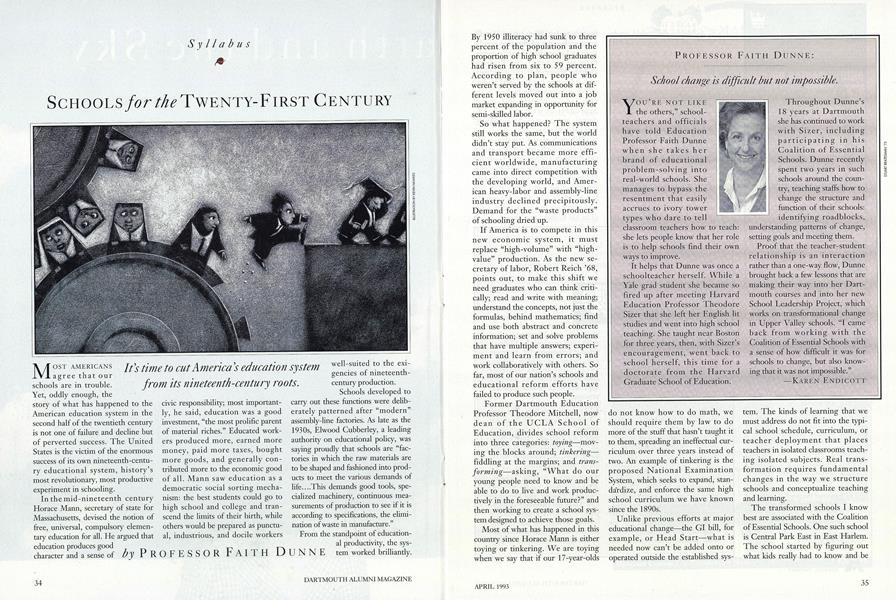

The transformed schools I know best are associated with the Coalition of Essential Schools. One such school is Central Park East in East Harlem. The school started by figuring out what kids really had to know and be able to do before they could graduate. Students are organized into teams of 80; each team has four teachers. The day is set up in two long blocks of time for studies in the humanities and in math and science. Teachers plan together each day, both for individual students and groups; coordinate curricula for all 80 students when possible; and make sure that everything taught feeds into everything else so students have a sense of the coherence of knowledge. The curriculum is based in problem-solving and critical thinking. Students read, write, and apply math all the time, not just in specific classes. And their education extends into the wider world as they carry out community service projects run by volunteers. "I'm out of compliance with most of the city regulations and about half the state regulations all the time," says Principal Debbie Meier. But she gets away with it because her students' reading scores are among the highest in the city (an incidental but useful byproduct of what she is really doing), and because she gets excellent national press.

Will such transformations become more widespread? The will is out there, but it needs support, and money, and applause for risk-taking. Otherwise, reform will dwindle into the tinkering and toying that will fail to make our next generation into a competitive work force. Each of us has to make that choice.

Its time to cut America's education systemfrom its nineteenth-century roots.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

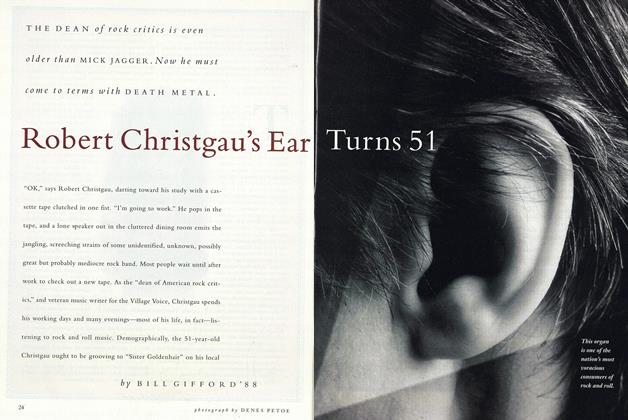

FeatureRobert Christgau's Ear Turns '51

April 1993 By BILL GIFFORD '88 -

Feature

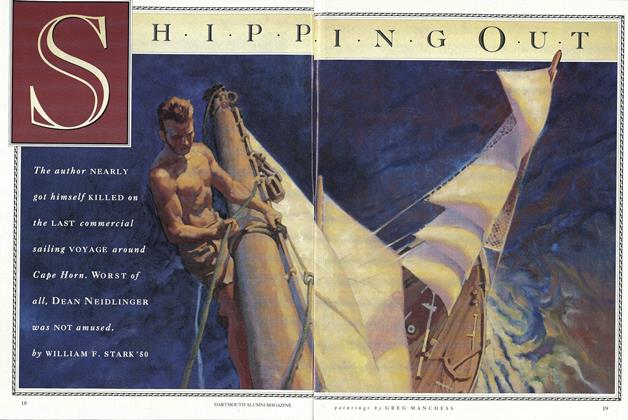

FeatureShipping Out

April 1993 By WILLIAM F. STARK '50 -

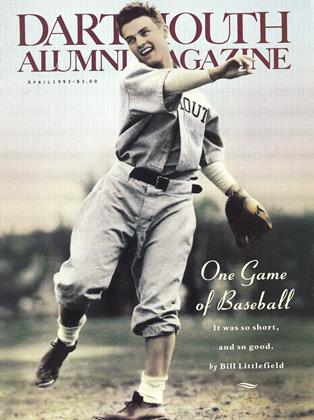

Cover Story

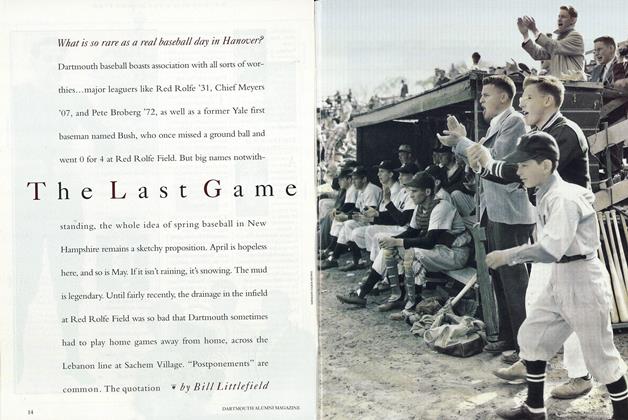

Cover StoryThe Last Game

April 1993 By Bill Littlefield -

Feature

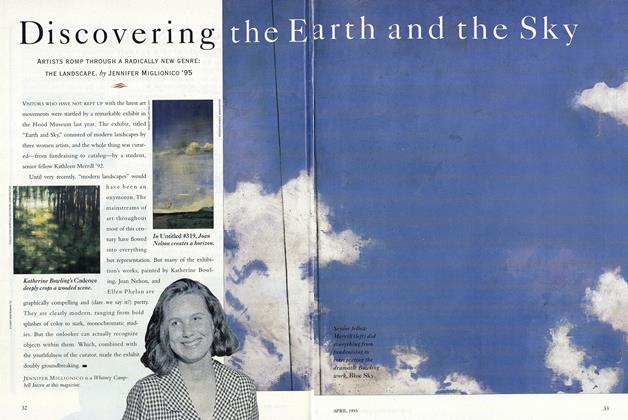

FeatureDiscovering the Earth and the Sky

April 1993 By Jennifer Miglionico '95 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

April 1993 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleNothing Less Than a Hero

April 1993 By James O. Freedman

Article

-

Article

Article"Hitches" and Science

March 1950 -

Article

ArticleHonors for Henrys

November 1983 -

Article

ArticleCan't We Get Along?

Nov/Dec 2007 -

Article

ArticleEmerson's Historic Visit

January 1939 By Herbert Faulkner West '22 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

OCTOBER 1931 By W. H. Ferry '32 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

April 1937 By William B. Rotch ’37