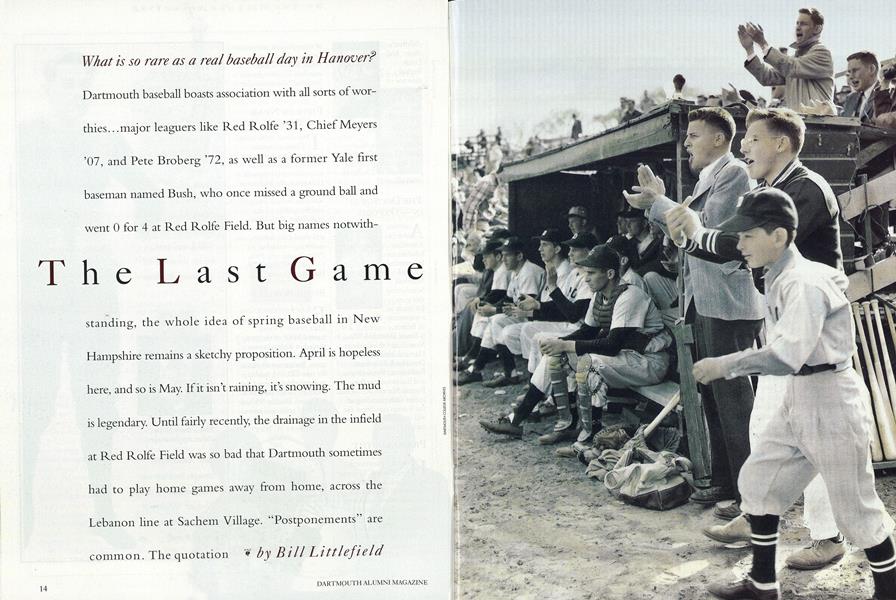

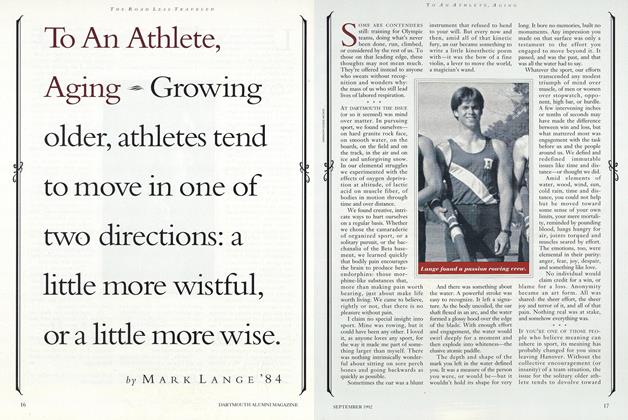

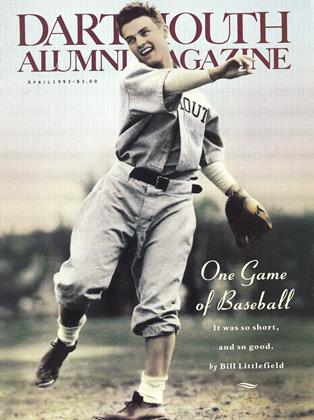

What is so rare as a real baseball day in Hanover? Dartmouth baseball boasts association with all sorts of worthies.. major leaguers like Red Rolfe '31, Chief Meyers '07, and Pete Broberg '72, as well as a former Yale first baseman named Bush, who once missed a ground ball and went 0 for 4 at Red Rolfe Field. But big names notwith- standing, the whole idea of spring baseball in New Hampshire remains a sketchy proposition. April is hopeless here, and so is May. If it isn't raining, it's snowing. The mud is legendary. Until fairly recently, the drainage in the infield at Red Rolfe Field was so bad that Dartmouth sometimes had to play home games away from home, across the Lebanon line at Sachem Village. Postponements are common. The quotation marks are because lots of the rainouts and snowouts and windchillouts are never made up. Scheduling baseball in Hanover is either an act of faith or an exercise in self-delusion, depending upon the theological underpinnings of those involved.

So when a real baseball day does manifest itself somewhere between exams and spring break, and when there is actually a home game scheduled for that day, those in attendance are likely to feel lucky to the point of giddiness. Or at least that is the way I felt early in May when I arrived in town to see Dartmouth and Holy Cross play a brisk and thoroughly satisfying nine innings. In the sunshine and good company, it was a constant effort to remind myself I was there to work.

Since I'd never been to Rolfe Field, I arrived early to gather ambiance. It was everywhere. The dugouts -were made of brick; pine trees stretched along the fence in left field. Somebody had wired the scratchy loudspeaker behind home plate to the radio broadcast of that day's Red Sox game, a bloated, untidy affair that would lumber along for three and a half hours. Dartmouth and Holy Cross would finish their business in a little less than two. There were other important distinctions. Up behind the Dartmouth dugout, a young man with the College radio station was tinkering with wires and cables. He wore a T-shirt that said "Dork" across the back. There are a lot of dorks in any major league crowd, of course, but I've never seen one who wore the appellation for the world to see.

The game itself began badly for the home team. Rick MacDonald '94 walked the first man he faced. A sacrifice bunt and fly ball later, he looked as if maybe he was still worrying a little about the free pass. He fell behind in the count early, throwing as if he felt he had no pitches to waste. The Holy Cross cleanup hitter jumped on a fastball that was much too good and hit it over the fence in left center and beyond the pine trees and the street as the crowd groaned or gasped. A long home run is a thing of beauty anywhere; it is a reminder, always quick and oddly surprising, no matter how often you've seen it, of how fast the tight, controlled struggle between the pitcher and the batter can disappear into the far distance. No wonder hyperbolic sportswriters sometimes call home runs "rockets" or "spaceshots." Each suddenly carries the imagination to some new place lor a moment. This home run was a little too much for Red Rolfe Field. It ended up on a lawn between a white house and a house that will be white again someday. Mark Roman, who had hit the thing, trotted, businesslike, around the bases. It is one of the charms of baseball that the most admirable hitters still endeavor to look as if they have done nothing special when they turn a fastball around with their wrists and hips, changing the game utterly, bringing their own fans to their feet and reducing those on the other side to murmurs of admiration. Ted Williams never acknowledged that he'd accomplished anything much when he was running out his dingers. Neither did Mark Roman.

Pitcher Mac Donald hit the next batter and walked the one after that, but before the game could sour entirely for Dartmouth, the Holy Cross first baseman popped up to end the inning.

The bottom of the first offered only a brief promise that Dartmouth might retaliate. Rightfielder John Clifford '95, batting second, took a pitch on the hip with a thump audible across the crowded bleacher. (There were, by this time, about 200 fans on hand.) A man with a sand-colored mustache and a sky-blue golf cap shouted, "Okay! We'll take it! That's a start!" which is the sort of thing that is easy for fans in the soft sunshine and easy breezes to say. Nobody's throwing anything at them. Regrettably for readers hoping for an unblemished pastoral interlude here, that was not the only semi-dumb thing a tan said on that May afternoon. An inning later a lone Dartmouth rooter standing in the shadow of the football grandstand, the steel bones of which loom huge and hideous along the entire right field line of Rolfe as if to remind everyone which sport really matters in America, watched a Holy Cross batter offer weakly at a curve ball and shouted, "Take that skirt off and swing!" The batter responded by singling hard on the next pitch. An inning later, the Holy Cross catcher dropped a perfect bunt down the first base line and beat it out for a hit. An idiot somewhere down the bleacher screamed, "That's crap!" and the notion that Dartmouth has only knowledgeable baseball fans took another direct hit.

Which is not to say that knowledge and appreciation were absent that afternoon. In the sixth, the game having settled into a fine pitchers' duel in which neither team had hit safely over four innings, I became aware of a soft but excited voice behind me. I looked over my shoulder and saw, two rows back, a fellow with two canes and a baseball cap that read, "May Peace Prevail On Earth." An hour and a half earlier I'd watched, a little puzzled, as the same man had leaned over the fence that separates the fans from the field, talking with a couple of the Dartmouth players. Now he was telling his companion stories about some of the boys... how this one had been hurt, but appeared to be running well now, and how that one would be trying out for the U.S. National Team. I climbed up to the seat beside this fellow who turned out to be Stuart Griffin. He had been attending Dartmouth baseball games regularly for 12 years. He was a fan zealous enough to have traveled on the team bus to away games until the coach put a stop to it, gently explaining to Mr. Griffin that once in a while he needed a few minutes to talk to his players without anyone else in the audience.

"It's kind of funny that I've become so attached to the Dartmouth team," Mr. Griffin told me. "I went to Yale."

"Really?" I said. "What year did you graduate?"

"1939," he said.

The bleacher shifted slightly beneath me. "My father graduated from Yale in 1939," I said. "Bill Littlefield."

"Oh, sure," Mr. Griffin smiled. "I knew Bill Little- field. He was on the crew. A good crew. They went to England one year, didn't they? To compete at Henley. And then later on he had a drinking problem."

"Yes," I said. "Then he stopped drinking, and he counseled alcoholics for 14 years."

"Well, that's remarkable," he said.

"He's dead now?"

"He died in 1986," I said. "In the fall."

"Well," Mr. Griffin smiled. "I remember him. He was a good golfer, too, wasn't he? And I remember many of his friends."

Poet Donald Hall once characterized baseball as "fathers playing catch with sons," which is lovely enough. But here in the bleacher was even more. Here was the memory of my father, alive and smiling before me, an oarsman, a golfer, a good man with friends remembered. And we hadn't played catch in 30 years. When we had played, he had praised my young arm lavishly and wondered aloud why I didn't pitch. This was a lunatic notion. I had neither speed nor control. But such was the extravagant love of a non-baseball player for his only son. It was a fine memory to savor, next to my father's old classmate. So were those of weekend afternoons at the Polo Grounds with my father, watching Willie Mays and the New York Giants play, and a trip to Cooperstown, just the two of us. For a couple of days, at the age of nine or so, I wandered through the Hall of Fame, over and over, wearing my own Giants uniform. I wouldn't take it off. Years later my father would delight in telling people that on the second day the lady at the door wouldn't take his money for my admission. He was, God bless him, too proud of his son to be embarrassed. He'd have preferred the golf course on a day like this fine one in May. But he'd have come with me if I'd asked him, and he'd have enjoyed my happiness at the ballpark.

Together Stuart Griffin and I turned our attention back to the game. Mark Roman, the same fellow who had hit the enormous home run for Holy Cross in the first inning, was up. On the mound, Rick Mac Donald had given way to David Angeramo '94, but the change seemed inconsequential to the mighty Roman. He swung hard at another fastball and drove it toward deepest center field. Joe Tosone, the Dartmouth centerfielder, took one look at the ball and turned his back to the infield. He ran hard for a time, snuck one peek over his left shoulder, and then reached up to pull Roman's shot out of the sky. It was as good a catch as I have ever seen at any level in any ballpark. There was the moment of silence which it always takes for people's brains to make sense of the fact that they have just seen something they couldn't have thought they would see, and then a burst of applause and shouting.

A few minutes later, in the bottom of the eighth inning, Joe Tosone '93 doubled sharply to left center and then scored on an error, putting Dartmouth on the board. Unhappily for fans of the home team, that was it. The score at the end of the afternoon was 3-1, Holy Cross.

When there were two outs in the home half of the ninth, Stuart Griffin said, "It's such a beautiful day. It's a shame we can't watch more."

"It surely is," I agreed. "But I'm glad I met you. I've enjoyed talking to you. It means something to me that you knew my father and remembered him so well."

All around us now men and women and boys and girls were rising from their seats, picking up their jackets, making plans for an early dinner or a party somewhere. There was the clatter of shoes on the metal bleacher and the bumping and scuffling of a lot of people trying to leave at once, so I wasn't sure whether Mr. Griffin had understood me or even heard me.

Then he said, "It is so short, and so good."

So perhaps he had

For years, those in attendance on a rare spring dayhave felt lucky, even giddy.

I arrived early at Red Rolfe Field togather ambiance. It was everywhere.

BILL LITTLEFIELD is sports editorof National Public Radio.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

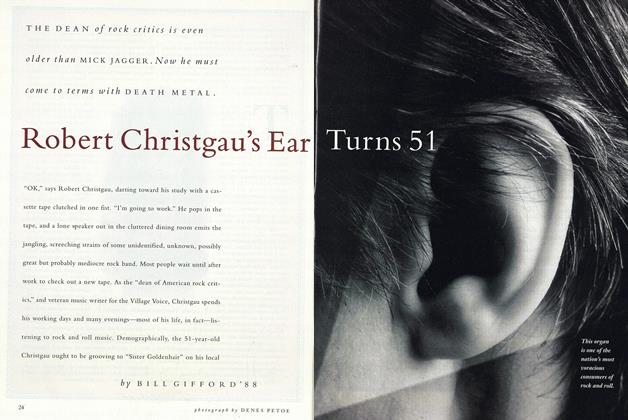

FeatureRobert Christgau's Ear Turns '51

April 1993 By BILL GIFFORD '88 -

Feature

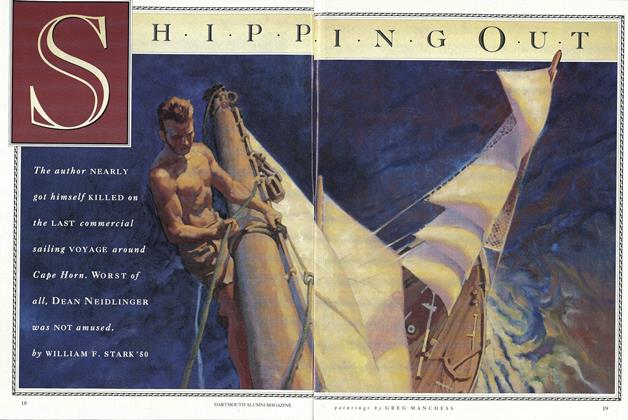

FeatureShipping Out

April 1993 By WILLIAM F. STARK '50 -

Feature

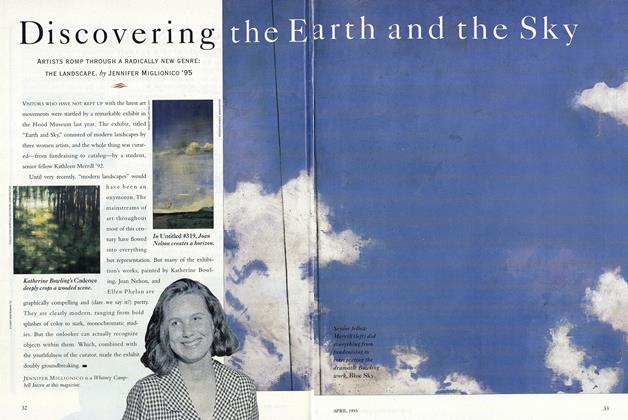

FeatureDiscovering the Earth and the Sky

April 1993 By Jennifer Miglionico '95 -

Article

ArticleSchools for the Twenty-First Century

April 1993 By Professor Faith Dunne -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

April 1993 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleNothing Less Than a Hero

April 1993 By James O. Freedman