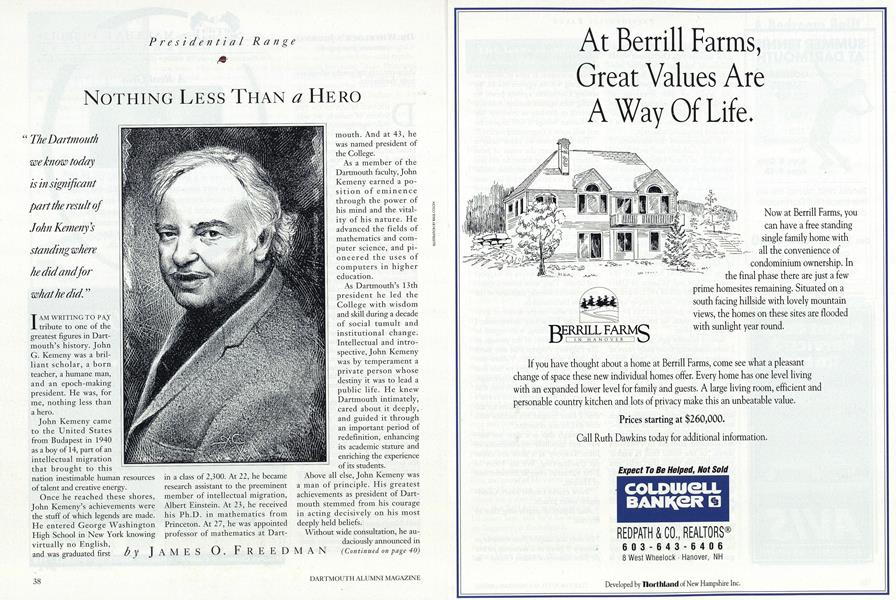

"The Dartmouth we know today is in significant part the result of John Kemeny's standing where he did and for what he did."

I AM WRITING TO PAY tribute to one of the greatest figures in Dartmouth's history. John G. Kemeny was a brilliant scholar, a born teacher, a humane man, and an epoch-making president. He was, for me, nothing less than a hero.

John Kemeny came to the United States from Budapest in 1940 as a boy of 14, part of an intellectual migration that brought to this nation inestimable human resources of talent and creative energy.

Once he reached these shores, John Kemeny's achievements were the stuff of which legends are made. He entered George Washington High School in New York knowing virtually no English, and was graduated first in a class of 2,300. At 22, he became research assistant to the preeminent member of intellectual migration, Albert Einstein. At 23, he received his Ph.D. in mathematics from Princeton. At 27, he was appointed professor of mathematics at Dartmouth. And at 43, he was named president of the College.

As a member of the Dartmouth faculty, John Kemeny earned a position of eminence through the power of his mind and the vitality of his nature. He advanced the fields of mathematics and computer science, and pioneered the uses of computers in higher education.

As Dartmouth's 13th president he led the College with wisdom and skill during a decade of social tumult and institutional change. Intellectual and introspective, John Kemeny was by temperament a private person whose destiny it was to lead a public life. He knew Dartmouth intimately, cared about it deeply, and guided it through an important period of redefinition, enhancing its academic stature and enriching the experience of its students.

Above all else, John Kemeny was a man of principle. His greatest achievements as president of Dartmouth stemmed from his courage in acting decisively on his most deeply held beliefs.

Without wide consultation, he audaciously announced in his inaugural address that Dartmouth would rededicate itself to its original mission of educating Native Americans. Shortly after he became president, in the wake of the invasion of Cambodia and the shootings at Kent State, he canceled classes for reflection and discussion—the action of a wise and pragmatic educator.

He championed the admission of minority students and established the Office of Equal Opportunity and Affirmative Action. Appointed by President Jimmy Carter to chair the commission to investigate the nuclear accident at Three Mile Island, he submitted a report sharply critical of the nuclear power industry and its federal regulators.

John Kemeny presided over Dartmouth's transformation into a coeducational institution. He was, of course, the first president to address the student body with the words, "Men and Women of Dartmouth." In the fall of 1972, when he first enunciated that simple salutation in the gentle accent of his Hungarian youth, he received a resounding ovation.

Several months ago, when he and I were discussing those early years of coeducation, he told me, with characteristic wit, how he used to assert that there was, indeed, a place for an all-male college—and that that place was Williams.

Finally, with eloquence as well as action, John Kemeny inspired each member of the Dartmouth familyas he said in his 12 th and final commencement address in 1981—to listen "to the voice that is within yourself—the voice that tells you that mankind can live in peace, that mankind can live in harmony, that mankind can live with respect for the rights and dignity of all human beings."

With words that are as powerful today as they were when he spoke them, he urged that graduating class to reject "a voice heard in many guises throughout history—which is the most dangerous voice you will ever hear. It appeals to the basest instincts in all of us—it appeals to human prejudice. It tries to divide us by setting whites against blacks, fey setting Christians against Jews, by setting men against women. And if it succeeds in dividing us from our fellow human beings it will impose its evil will upon a fragmented society."

The Dartmouth we know today is in significant part the result of John Kemeny's standing where he did and for what he did: coeducation, racial diversity, academic excellence, and generosity of spirit. He moved Dartmouth forward in innumerable ways and gave over to us an institution enhanced in stature and promise.

To Sheba and me—from the time we were new to Dartmouth ourselves, anxious to further the work that President Kemeny had done so much to advance John and Jean Kemeny were invaluable sources of support and advice. They were kindred spirits and treasured friends, emblems of the best that Dartmouth is.

As one who has the honor of serving in the Wheelock Succession, I find myself thinking, with regard to President Kemeny, of the passage in The Pilgrim's Progress that sets forth the dying words of Mr. Valiant-for-Truth: "My sword I give to him that shall succeed me in my pilgrimage, and my courage and skill to him that can get it. My marks and scars I carry with me, to be a witness for me that I have fought his battles who now will be my rewarder."

Although this is a time for sorrow, our indelible recollections of John Kemeny as a man are cause for thanksgiving. We say today of John Kemeny, even as Horatio said of Hamlet,

"Now cracks a noble heart. Goodnight, sweet prince,

And flights of angels sing thee to thy rest!"

This essay was adapted from remarks onJanuary 9 given at a memorial servicefor John Kemeny in Rollins Chapel.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureRobert Christgau's Ear Turns '51

April 1993 By BILL GIFFORD '88 -

Feature

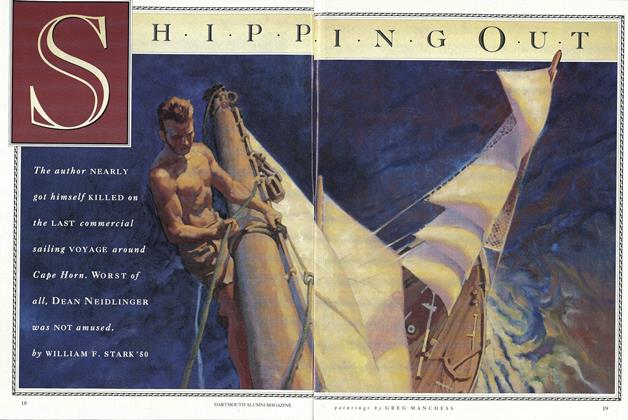

FeatureShipping Out

April 1993 By WILLIAM F. STARK '50 -

Cover Story

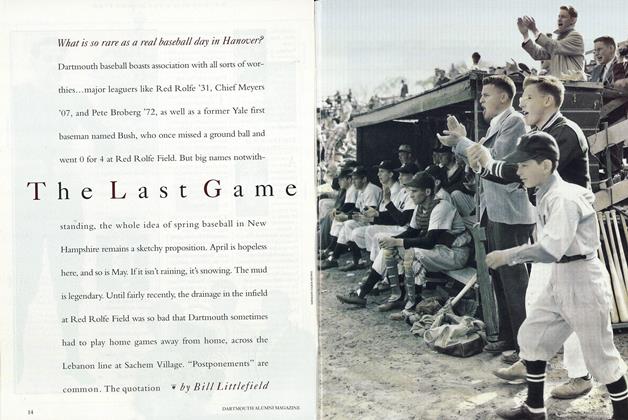

Cover StoryThe Last Game

April 1993 By Bill Littlefield -

Feature

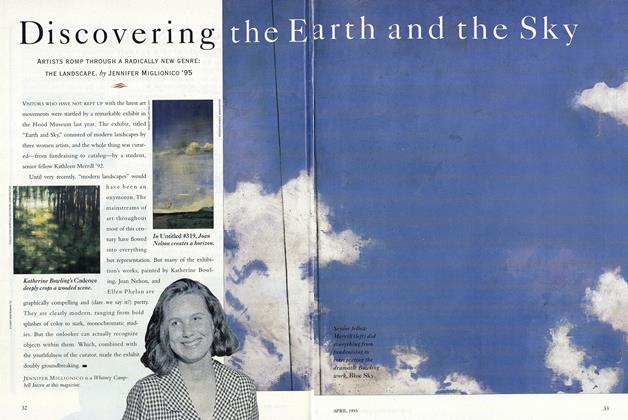

FeatureDiscovering the Earth and the Sky

April 1993 By Jennifer Miglionico '95 -

Article

ArticleSchools for the Twenty-First Century

April 1993 By Professor Faith Dunne -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

April 1993 By "E. Wheelock"

James O. Freedman

-

Article

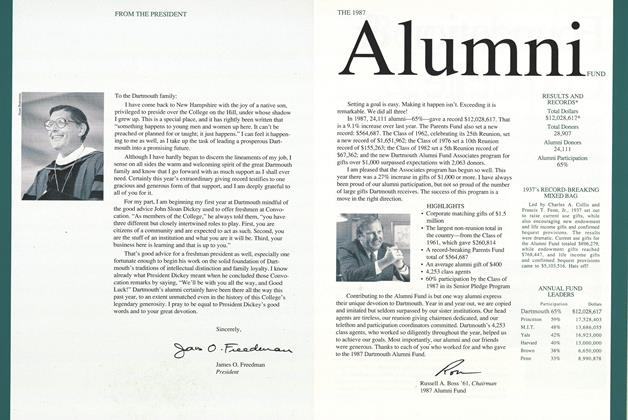

ArticleFROM THE PRESIDENT

OCTOBER • 1987 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleCompared to What

June 1992 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Article

ArticleThe Time Allotted Us

June 1994 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleEssayists and Solitude

November 1994 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleLiving Well by Doing Good

NOVEMBER 1997 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThe Uncertain Future of Medical Education

DECEMBER 1997 By James O. Freedman

Article

-

Article

ArticleAdmission-Aid Board

FEBRUARY 1963 -

Article

ArticleElective Perfectibility

May 1976 -

Article

ArticleSLICES OF LIFE

Nov/Dec 2007 -

Article

ArticleMy Dog Likes It Here

MAY 1978 By COREY FORD -

Article

ArticleDEMOCRACY IN TRANSITION

January 1947 By HADLEY CANTRIL -

Article

ArticleWanted: Road-trip Messerly

November 1980 By Parker B. Smith '66