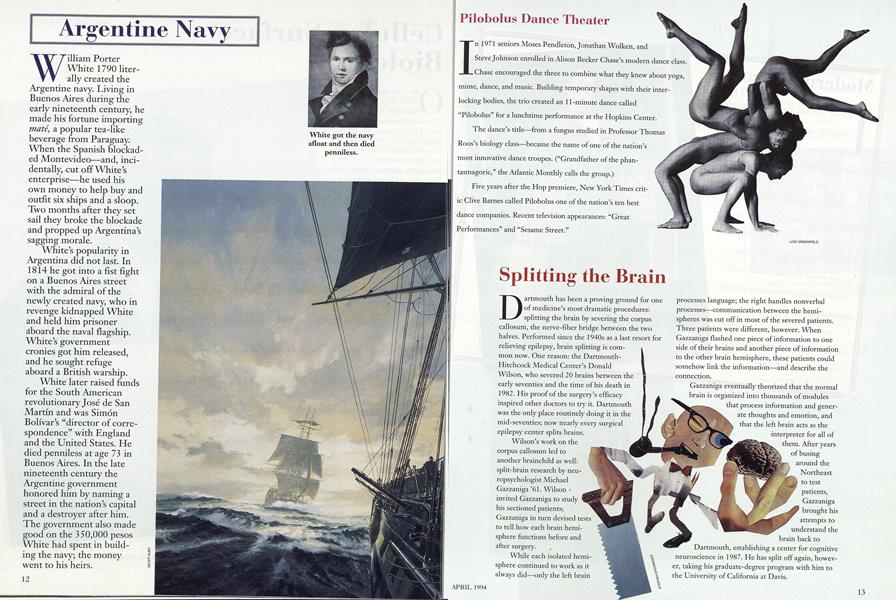

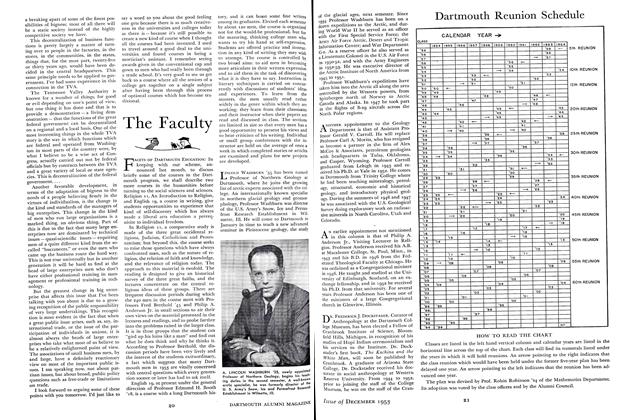

Dartmouth has been a proving ground for one of medicine's most dramatic procedures: splitting the brain by severing the corpus callosum, the nerve-fiber bridge between the two halves. Performed since the 1940s as a last resort for

relieving epilepsy, brain splitting is common now. One reason: the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center's Donald Wilson, who severed 20 brains between the early seventies and the time of his death in 1982. His proof of the surgery's efficacy inspired other doctors to try it. Dartmouth was the only place routinely doing it in the mid-seventies; now nearly every surgical epilepsy center splits brains.

Wilson's work on the corpus callosum led to another brainchild as well: split-brain research by neuropsychologist Michael Gazzaniga '61. Wilson invited Gazzaniga to study his sectioned patients; Gazzaniga in turn devised tests to tell how each brain hemisphere functions before and after surgery.

While each isolated hemisphere continued to work as it always did—only the left brain processes language; the right handles nonverbal processes communication between the hemispheres was cut off in most of the severed patients. Three patients were different, however. When Gazzaniga flashed one piece of information to one side of their brains and another piece of information to the other brain hemisphere, these patients could somehow link the information and describe the connection.

Gazzaniga eventually theorized that the normal brain is organized into thousands of modules that process information and generate thoughts and emotion, and that the left brain acts as the interpreter for all of them. After years of busing around the Northeast to test patients, Gazzaniga brought his attempts to understand the brain back to Dartmouth, establishing a center for cognitive neuroscience in 1987. He has split off again, however, taking his graduate-degree program with him to the University of California at Davis.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryROSTER OF DARTMOUTH'S GIFTS TO THE WORLD

April 1994 -

Article

ArticleThe Greatest Books by Dartmouth Authors

April 1994 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1993

April 1994 By Christopher K. Onken, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1981

April 1994 By Karen McKeel Calby, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1989

April 1994 By Dan Parish, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1983

April 1994 By Deborah Michel Rosch.