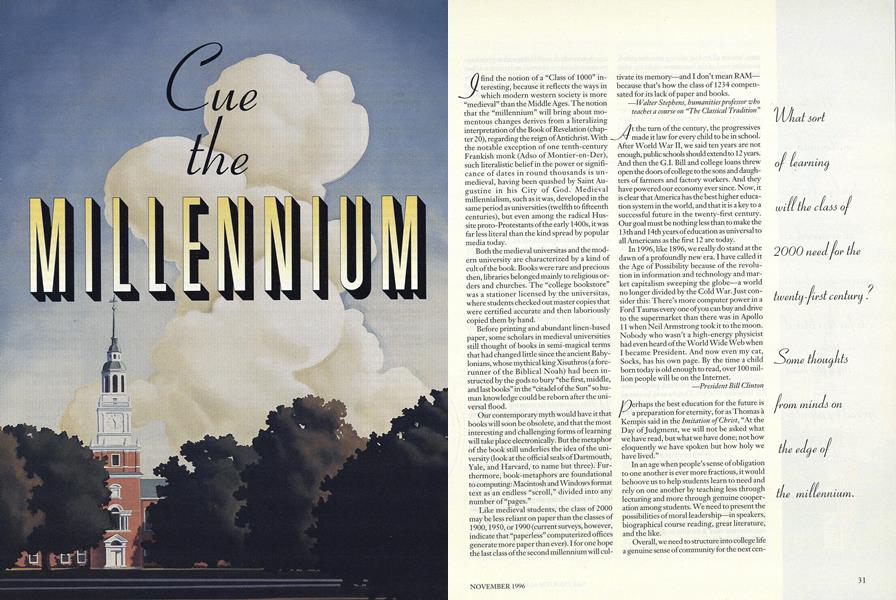

I find the notion of a "Class of 1000" interesting, because it reflects the ways in which modern western society is more "medieval" than the Middle Ages. The notion that the "millennium" will bring about momentous changes derives from a literalizing interpretation of the Book of Revelation (chapter 20), regarding the reign of Antichrist. With the notable exception of one tenth-century Frankish monk (Adso of Montier-en-Der), such literalistic belief in the power or significance of dates in round thousands is unmedieval, having been quashed by Saint Augustine in his City of God. Medieval millennialism, such as it was, developed in the same period as universities (twelfth to fifteenth centuries), but even among the radical Hussite proto-Protestants ofthe early 1400s, it was far less literal than the kind spread by popular media today.

Both the medieval universitas and the modern university are characterized by a kind of cult of the book. Books were rare and precious then, libraries belonged mainly to religious orders and churches. The "college bookstore" was a stationer licensed by the universitas, where students checked out master copies that were certified accurate and then laboriously copied them by hand.

Before printing and abundant linen-based paper, some scholars in medieval universities still thought of books in semi-magical terms that had changed little since the ancient Babylonians, whose mythical king Xisuthros (a forerunner of the Biblical Noah) had been instructed by the gods to bury "the first, middle, and last books" in the "citadel of the Sun" so human knowledge could be reborn after the universal flood.

Our contemporary myth would have it that books will soon be obsolete, and that the most interesting and challenging forms of learning will take place electronically. But the metaphor of the book still underlies the idea of the university (look at the official seals of Dartmouth, Yale, and Harvard, to name but three). Furthermore, book-metaphors are foundational to computing: Macintosh and Windows format text as an endless "scroll," divided into any number of "pages."

Like medieval students, the class of 2000 may be less reliant on paper than the classes of 1900,1950, or 1990 (current surveys, however, indicate that "paperless" computerized offices generate more paper than ever). I for one hope the last class of the second millennium will cultivate its memory—and I don't mean RAM-because that's how the class of 1234 compensated for its lack of paper and books.

—Walter Stephens, humanities professor whoteaches a course on "The Classical Tradition"

At the turn of the century, the progressives made it law for every child to be in school. After World War II, we said ten years are not enough, public schools should extend to 12 years. And then the G.I. Bill and college loans threw open the doors of college to the sons and daughters of farmers and factory workers. And they have powered our economy ever since. Now, it is clear that America has the best higher education system in the world, and that it is a key to a successful future in the twenty-first century. Our goal must be nothing less than to make the 13 th and 14th years of education as universal to all Americans as the first 12 are today.

In 1996, like 1896, we really do stand at the dawn of a profoundly new era. I have called it the Age of Possibility because of the revolution in information and technology and market capitalism sweeping the globe—a world no longer divided by the Cold War. Just consider this: There's more computer power in a Ford Taurus every one of you can buy and drive to the supermarket than there was in Apollo 11 when Neil Armstrong took it to the moon. Nobody who wasn't a high-energy physicist had even heard of the World Wide Web when I became President. And now even my cat, Socks, has his own page. By the time a child born today is old enough to read, over 100 million people will be on the Internet.

-President Bill Clinton

Perhaps the best education for the future is a preparation for eternity, for as Thomas a Kempis said in the Imitation of Christ, "At the Day of Judgment, we will not be asked what we have read, but whatwe have done; nothow eloquently we have spoken but how holy we have lived."

In an age when people's sense of obligation to one another is ever more fractious, it would behoove us to help students learn to need and rely on one another by teaching less through lecturing and more through genuine cooperation among students. We need to present the possibilities of moral leadership—in speakers, biographical course reading, great literature, and the like.

Overall, we need to structure into college life a genuine sense of community for the next century, lest we all end up staring into the mindnumbing void of the Internet wondering what has gone so horribly wrong.

Randy-Michael Testa, assistant visitingprofessor of education

The present education system model is location-based; the students come to Dartmouth's Hanover campus for four years, and faculty reside here. In my model they would get together in a shared virtual world and work on projects from their own remote site on the Internet or World Wide Web. There are some companies working on these so-called social virtual realities.

Once academic courses inhabit both a physical presence and a virtual cyberspace, students, visiting teachers, and alumni, expert in specific topics, can participate from remote sites. They can build vehicles, such as cars and planes, design structures in architecture or molecular design. Once we make this technology part of the classroom, the physical classroom as we know it, becomes a virtual classroom. It no longer has the usual walls, and can be designed according to who participates, with what bandwidth, computational power, and according to whether the interactions happen in the same time space or asynchronously as electronic mail does.

The use of multi-user virtual environments will transform education in the twenty-first century and Dartmouth, because of its remote location, should take a lead in this.

Joseph Rosen, M.D., plastic surgeon whoteaches an engineering freshman seminar on"artificial people"; head of a company creating acomputerized "virtual person "for use by doctors.

People have to be able to read, people have I to be able to write. They have to be able to scout out information, to be detectives, learning how to get hold of information, whether they get it in the library or on the Internet.

The training of the mind is not going to be any different. Things aren't going to change.

Jere Daniell '55, Dartmouthhistory professor specializing inNew England history

After they decide what to call themselves (the "naughts" is my favorite choice, what with the potential for "naughty"), they will need to figure out how to face the calendar equivalent of a blank page. It's a remarkable pressure to put on people still trying to figure out whether they'll be able to get up for an eight o'clock class.

Women, particularly, will face life-changing choices which could bring either great happiness or the abyss of social and emotional isolation, as well as lonely death. We will increasingly need to drop the inherited and scripted version of our lives and come to terms with the fact that the best of life is about improvisation, invention, and irreverence. The world needs women willing to forfeit private privilege for public justice, who will see themselves as responsible for all of the future, not just the futures of our children, and who are willing not only to laugh at the absurdities of the world (a good start) but to work (diligently, urgently, happily) to create balance and equality.

Regina Barreca '79, editor, The Penguin Book of Women's Humor; author of Sweet Revenge and Perfect Husbands (And Other Fairy T ales). Associate professor of English atthe University of Connecticut

The College environment must do more to promote healthful lifestyles. The American health care system of the twenty-first century will be hard-pressed, and we will need to do a better job of taking charge of our own health. Smoking, unhealthful diet and activity patterns, and alcohol and other drug abuse are the three main causes of preventable deaths in the United States, claiming more than 900,000 lives each year. Adolescents feel immortal, but they are not. All too many young Americans in college make lifestyle choices about tobacco, diet, and alcohol that amount to an early death sentence. In curricular as well as co-curricular programs, colleges need to be as concerned about healthy bodies as healthy minds.

C. Everett Koop '37, M.D., Sc.D., formersurgeon general, head of Dartmouth'sKoop Institute for training doctors.

What our students entering the twenty-first century need is, first and foremost, factual and solid information, a basis from which they can then develop their intellectual capabilities without falling prey to half-truths, false assumptions, speculations, and intentional distortions. In our age of easy multimedia access and cyberspace, it is all the more important that they learn to distinguish between credible sources and sensationalist news, often hastily put together. Reading a text in its totality before talking about it is essential for forming one's own opinion. One has to familiarize oneself with all facts of history and not single out one event to use as a prism for the entire history of a country. Fragmentation of knowledge is dangerous, and the media and the Internet are the worst offenders. We have to teach how facts differ from virtual reality, and how to reduce or eliminate vast amounts of unconnected and superficial information. Education in this area will increasingly become a prerequisite for any serious learning.

Konrad Kenkel, German professor, headsMiddlehuiy summer language institute

no longer will students be required to memorize large bodies of facts since such information can be obtained from databases on the Internet. The challenge for the College is to provide students with the skills needed to handle this overwhelming wealth of information and the proper perspective on important world issues. The skills common to independent research, such as data collection by the scientific method and critical analysis of cause-and-effect relationships, must be emphasized over breadth of coverage and factual knowledge.

George Langford, Dartmouth'sE.E. Just Professor of Biology

if you had asked in 1975, when I was a sophomore at Dartmouth, what will be the big issues of the 1990s, it is virtually certain that what would not have made the list is the booming economic growth of Japan. Another is the phenomenal pace in Asia, and another the breakup of the Soviet Union. Of the top four of five developments in a geopolitical context that have reshaped the face of the earth in the last five to seven years, it is probably safe to say that we would have come up with none of them as realistic possibilities. That suggests to me our ability to see into the future is not great.

I would wager that much of what I was taught in, for example, Earth Sciences II my sophomore year no longer holds either. Scientists have moved well beyond in their understanding. The rote memorization I did turned out not to be particularly useful. What is more useful is what I was taught by way of thinking about the origins of the universe, the origins of the earth.

So what skills do we want people to graduate having when so much of what will be shoved at them in life will turn out to be fleeting, insufficiendy analytical, absurd, or patently false? We will continue to argue about what should be in the canon of great ideas and great authors, but I will leave that for another debate. Really the most critical thing now, as it always has been, is the fundamental aspect of a liberal arts education. In the end it's less important what specific body of knowledge gets taught than what certain skills—like thinking, like ananlytical reasoning, like logic, like careful writing, careful communication, precision of thought, precision of language. Those are the things that people are going to come back and use time and time and time again.

-Susan Dentzer '77, Dartmouth CollegeTrustee, economics corespondentfor U.S. News & World Report

What sort of education will the class of 2000 need for the twenty-first century? More technology, more science. More need to study and understand not only the self but also the other. More need for colleges and universities to inculcate the intellectual desire or habit of mind of being a life-long learner-one who continues to think, to read, to remain intellectually, passionately engaged with the world and its issues. And, amidst all this rapid change and information proliferation, more need to be sure that the urgency of action does not crowd out invaluable reflection.

James O. Freedman, president,Dartmouth College

In general, I would echo President Freedman on the benefits of a liberal education for the twenty-first century: the world is changing at a bewildering pace, md the values and understandings acquired through the kind of education Dartmouth has to offer may be one's only secure moorings.

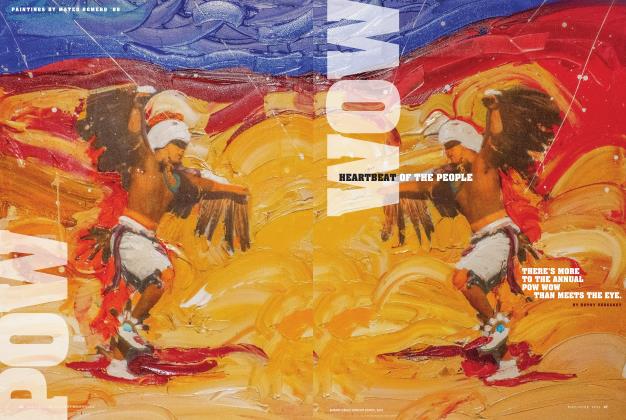

I'd stress the importance of an education that conveys a sense of history that goes back thousands of years, not just a couple of centuries. Indian people are the only people who have been in the United States for more than a few hundred years. History may not always be our best guide for the future, but we need to know we have a history, that it stretches far back in time, and that it is a story of continual change. By better appreciating the Indian strand that runs through the American past and continues into our present, we can, perhaps, see some valuable lessons for surviving the hard times that will undoubtedly be part of our experiences in the centuries ahead.

Colin Calloway, professor of NativeAmerican studies and history,new John Sloan Dickey Third CenturyProfessor in the Social Sciences

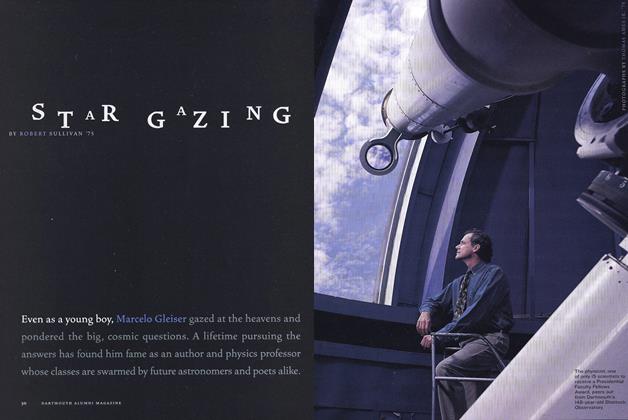

It's crucial for students with a liberal arts education to really understand what science is about and how to deal with it; not to think of science as this big-headed, horrible monster. The curriculum and the philosophy have to reflect the increasingly important role that science plays in all our lives in all respects—from CD players to computers to quartz alarm clocks. The evolution of ideas in physics affected our vision of the world, so science affects our understanding of nature and of the universe. In my little effort to improve on people's science education, I developed a course with History Professor Richard Kramer, which the students call Physics for Poets. Through it they can learn to talk about black holes and big bangs and quasars and quantum mechanics, and impress their friends at parties.

Marcelo Gleiser, physics professor,member of Dartmouth's policy-makingCommittee on Instruction

There needs to be a renewed attention paid to the principles of democracy and its weaknesses—not only in theory but in practicebecause our democracy is going to be sorely tested in the next century. It's troubling to me how often people who are otherwise well-educated take short cuts past certain fundamental rights and liberties that are prerequisites of a democracy.

Elections alone don't make democracy. You have to have a whole set of institutions, constitutional principles, governmental structure of checks and balances, a general respect for the law, and all kinds of cultural habits that can't just be invented from the top. These cultural habits, even in a society such as ours, where they're deeply rooted, have to be transmitted from generation to generation. Those habits are, in part, tolerance for varying opinion, and a way of debating and discussing issues that recognize the rights of people to have sharp differences. Out of those differences we can continue to forge the kind of country we had in the past.

David Shipler '64, Dartmouth Trustee,former New York Times reporter,Pulitzer Prizewinning author of Arab and Jew.

I fear for the future if we cannot or do not shift our system to more holistic, applied, and theoretical study of the issues of our day. Our current fragmented, departmentalized system is woefully unequal to the task of solving most contemporary problems. For example, environmental degradation cannot be solved by any one or even a few disciplines. They have complex, multiple dimensions demanding skills in economics, political science, geography, philosophy, biophysics, chemistry, and more. The same is true for most of the major problems of our time from particular scourges such as AIDS to more broadly based issues as ethnic/territorial/nationalistic/religious conflicts. We must find more efficient and imaginative methods of preparing students to deal with these cross/multi/inter/whatever disciplinary issues. The first step would be to engage the current departments in a discussion of ideas. Progress means educating our students to move beyond those who taught them.

George Demko, geography professor,former Geographer of the United States

The next century will be the century of human genetics, during which we will develop unprecedented understanding and control of the molecular bases of life. Discoveries in this area can prove liberating: freeing us all from many diseases and helping us reduce the biologically harmful consequence of our interventions in the environment. Or they can invite new and unimagined forms of oppression. The direction this and other new technologies take depends on the caliber and the leadership of the men and women we educate at schools like Dartmouth. If we define wisdom as the "knowledge of how to use knowledge," then places like Dartmouth must dedicate themselves to imparting not just information and skills but moral wisdom.

Ethics education must begin with the first year of college and continue through (and beyond) professional school. Students must be trained to understand complex scientific, technological, social, and legal issues, and to approach the solution of difficult problems through teamwork and multi disciplinary conversation. Classroom activities must be interactive: placing a premium not on communicating information (which each participant should learn to gather before class), but on the articulation and development of thoughtful and informed positions on the texts and issues under review.

If science and technology in the next century are to improve rather than worsen our lives, their direction must be monitored and shaped by informed, judicious, and ethically concerned citizens working together at all levels: from our legislatures, executive suites, and courts to our classrooms and laboratories. Dartmouth's role is to prepare its students to participate in and lead these efforts.

Ronald M. Green, John Phillips Professorof Religion and director of the Ethics Institute

Taday, after completing their college education, individuals look forward to at least 50 years of productive activity and achievement. Engineering is a rapidly changing field, and good engineers must be intellectually nimble. As the pace of life increases, so does the need for agile engineers. How do we at Thayer School educate engineers for a lifetime? Not by forcing narrow disciplines, but by providing instead the basic, interdisciplinary concepts on which all of engineering stands.

Elsa Garmire, dean,Thayer School of Engineering

Students today are accustomed to thinking about education as the mastery of a set of skills, yet they will be better served by the development of a particular set of attitudes. In my view, the habits of mind acquired through a first-class liberal arts education are still the best preparation for the uncertain future that awaits us in the twenty-first century.

First, students will need to learn how to teach themselves, because they are likely to encounter intellectual puzzles as adults that are not covered by today's curriculum. Methodological training will probably prove more useful than substantive knowledge, but even well-established modes of inquiry may quickly become obsolete. Thus, the well-educated individual should know how to define a problem, how to apply theories and compile evidence, how to validate results, and how to re-examine conclusions in light of alternative explanations.

Second, students will need to develop strong characters to anchor them in a complex and chaotic world. They can accomplish this goal through exploration of the classics in literature, philosophy, and religion, and through careful reading of history. Most important, they will need to acquire the self-discipline, love of truth, respect for craftsmanship, and scorn for hypocrisy that still form the bedrock of a fine liberal education.

Linda L. Fowler, director of RockefellerCenter, professor of government

Unfortunately, I will not be around unless mummified, but I believe the following: The world of work is one of more temporary and parttime jobs, ones requiring new education for each job, and adults are likely to return to "school" four or five times in their lives; the concept of K-12 plus four college years will diminish. Learners will no longer assume their education is terminal (graduation/commencement), but cyclical through life. Lifetime learning will follow students' interests and return the joy to study.

Increased focus on world, problem solving, communication, and personal development in a more open, independent environment will take place, where "school" maybe a miniature laptop or a year-round home-learning station. All is possible by the advent of new technologies

way beyond our present imagination. If Buck Rogers seemed far out 50 years ago, computers as we know them today will seem archaic. Beam me up, Scotty.

Robert Binswanger '52, professor ofeducation, teaches a course in thehistory of American education

The class of 2000 will need to know a great deal about things in the twenty-first century, some of which are different from what we now know, for the landscape of human knowledge, like sand in the desert, is a continually shifting reality. They will need to know more about science and technology, become more conversant with international economics, economic interdependence and, if the human species is to endure and thrive, be a great deal more pro-active in promoting the healthy survival of the ecosystem that nurtures and maintains our little (unique?) planet in an infinite universe.

The most difficult challenge the class of 2000 will face in the twenty-first century is the very same one confronting us today: how better to deal with, if not eliminate, conflictive human interaction across "us" and "them" boundaries. When it comes to understanding and implementing ways of avoiding human conflict across racial, ethnic, gender, religious and national barriers, how much progress have we made? In a sense, it is much easier to acquire knowledge about things—science, technology, the global economy, cyberspace—than it is to learn how to manage human conflict. Why is it that in the late twentieth century, as examples, we are confronted with the burning of black churches across the nation, "ethnic cleansing" in Bosnia, religious warfare in Northern Ireland, racial terror in Burundi, terrorism in the Middle East and in the United States?

The truth of the matter is that the class of 2000 will need to know more about the human condition in the twenty-first century than we have learned about things in the past and present. Dartmouth, with its newly implemented curriculum and its commitment to diversity, is in an excellent position to empower the class of 2000 with the most powerful tool it will require in the twenty-first century—ease and familiarity with the reality of human diversity.

Ray Hall, professor and chair of department of sociology, Orvil E. Dryfoos Professor ofPublic Affairs, director ofProgramfom theComparative Study of Inter group Conflict inMultinational States, completing book on Ethnonationalism in Multinational States: A Comparative Approach

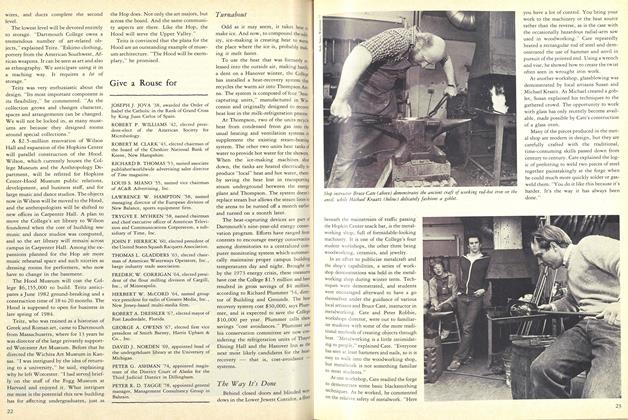

What sortof learningwill the class of2000 need for thetwenty-first century ?Some thoughtsfrom minds onthe edge ofthe millennium.

"Medieval millennialismdeveloped in theame period as universities, but itwad far less literalthan the kindspread by popularmedia today."Walter Stepliem

"There needs to berenewed attention tothe principled of democracy and itsweakness becauseour democracyis going to be sorelytested in thenext century." David shipler

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Billion Dollars

November 1996 By Rebecca Bailey -

Feature

FeatureThe Inside Story

November 1996 By Karl Furstenberg -

Cover Story

Cover StoryOught Ought

November 1996 By Joe Mehling '69 -

Article

ArticleWhat Beethoven Heard

November 1996 By Kathleen Burge '89 -

Article

ArticleA Two-for-One- Convocation and the Med School's 200th

November 1996 By E. Wheelock -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty's Turn to Give

November 1996 By Noel Perrin

Features

-

FEATURES

FEATURESHeartbeat of the People

MAY | JUNE 2021 By BETSY VERECKEY -

Feature

FeatureThe Responsibilities of Management

March 1956 By J. IRWIN MILLER -

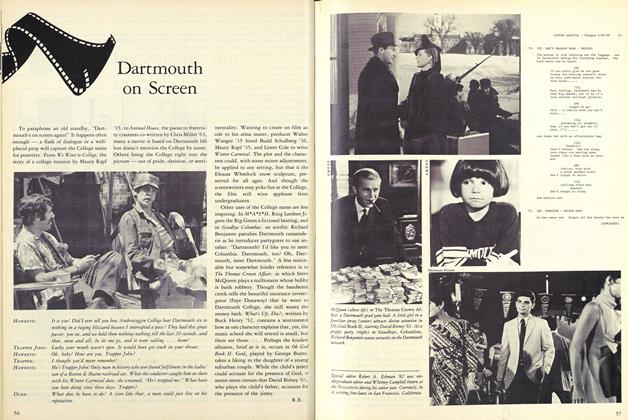

Feature

FeatureDartmouth on Screen

November 1982 By R.E. -

Feature

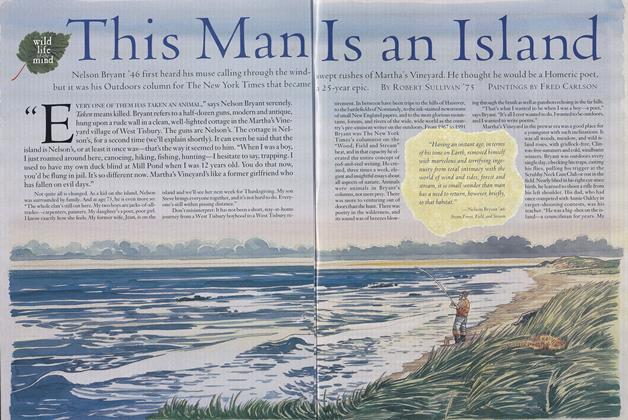

FeatureThis Man Is an Island

OCTOBER 1996 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryStar Gazing

July/Aug 2003 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

FeatureEnd of a Golden era

APRIL 1982 By Shelby Grantham