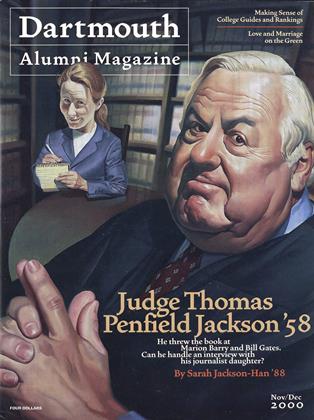

Father In Law

Keeping it all in the family, Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson ’58, the man who broke up Microsoft, submits to an interview with his journalist daughter.

Nov/Dec 2000 SARAH JACKSON-HAN ’88Keeping it all in the family, Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson ’58, the man who broke up Microsoft, submits to an interview with his journalist daughter.

Nov/Dec 2000 SARAH JACKSON-HAN ’88KEEPING IT ALL IN THE FAMILY,JUDGE THOMAS PENFIELD JACKSON '58,THE MAN WHO BROKE UP MICROSOFT, SUBMITS TO ANINTERVIEW WITH HIS JOURNALIST DAUGHTER.

MANDATORY MINIMUM JAIL TERMS MAY HAVE BEEN FOOLISH PUBLIC POLICY, BUT they were brilliant propaganda for my dad when he was trying to convince his children to stay away from drugs.

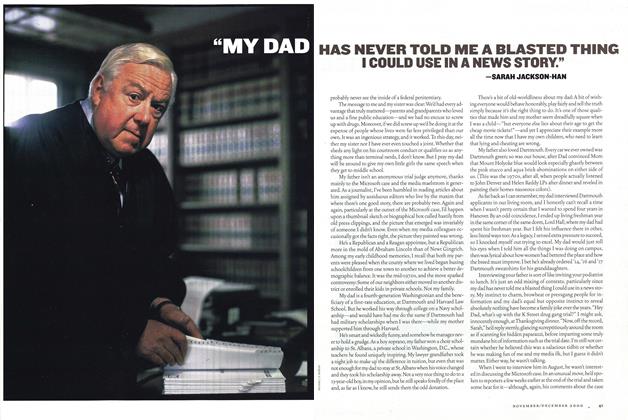

Years ago, before he was The Marion Barry Judge and The Microsoft Judge, my father, the Hon. Thomas Penfield Jackson, was an anonymous federal trial judge. He was also then the father of two lanky, long-haired teenage daughters who he feared might find themselves drawn into a debauched demimonde of illicit drugs.

Before the federal sentencing guidelines for drug crimes became law—mandating stiff jail terms even for small-time, novice drug offenders—my dad would recount to us in grim detail how illicit drugs had ravaged the lives of defendants who appeared in his courtroom. Later, after the guidelines took effect, he would describe the handful of cases that caused him genuine anguish. These were the college students and struggling single parents with no prior criminal records, whom my dad had no choice but to send to godforsaken federal jails for unduly long stretches because they'd been caught ferrying contraband that might ultimately end up in the hands of upper-middle-class kids in the suburbs. Privileged kids, he would say pointedly, peering over his reading glasses, who were also breaking the law but would probably never see the inside of a federal penitentiary.

The message to me and my sister was clear: Wed had every advantage that truly mattered—parents and grandparents who loved us and a fine public education—and we had no excuse to screw up with drugs. Moreover, if we did screw up wed be doing it at the expense of people whose lives were far less privileged than our own. It was an ingenious strategy, and it worked. To this day, neither my sister nor I have ever even touched a joint. Whether that sheds any light on his courtroom conduct or qualifies us as anything more than terminal nerds, I don't know. But I pray my dad will be around to give my own little girls the same speech when they get to middle school.

My father isn't an anonymous trial judge anymore, thanks mainly to the Microsoft case and the media maelstrom it generated. As a journalist, I've been humbled in reading articles about him assigned by assiduous editors who live by the maxim that where there's one good story, there are probably two. Again and again, particularly at the outset of the Microsoft case, I'd happen upon a thumbnail sketch or biographical box culled hastily from old press clippings, and the picture that emerged was invariably of someone I didn't know. Even when my media colleagues occasionally got the facts right, the picture they painted was wrong.

He's a Republican and a Reagan appointee, but a Republican more in the mold of Abraham Lincoln than of Newt Gingrich. Among my early childhood memories, I recall that both my parents were pleased when the county where we lived began busing schoolchildren from one town to another to achieve a better demographic balance. It was the mid-1970s, and the move sparked controversy: Some of our neighbors either moved to another district or enrolled their kids in private schools. Not my family.

My dad is a fourth-generation Washingtonian and the beneficiary of a first-rate education, at Dartmouth and Harvard Law School. But he worked his way through college on a Navy scholarship—and would have had me do the same if Dartmouth had had military scholarships when I was there—while my mother supported him through Harvard.

He's smart and wickedly funny, and somehow he manages never to hold a grudge. As a boy soprano, my father won a choir scholarship to St. Albans, a private school in Washington, D.C., whose teachers he found uniquely inspiring. My lawyer grandfather took a night job to make up the difference in tuition, but even that was not enough for my dad to stay at St. Albans when his voice changed and they took his scholarship away. Not a very nice thing to do to a 13-year-old boy, in my opinion, but he still speaks fondly of the place and, as far as I know, he still sends them the odd donation.

There's a bit of old-worldliness about my dad: A bit of wishing everyone would behave honorably, play fairly and tell the truth simply because it's the right thing to do. It's one of those qualities that made him and my mother seem dreadfully square when I was a child—"but everyone else lies about their age to get the cheap movie tickets!"—and yet I appreciate their example more all the time now that I have my own children, who need to learn that lying and cheating are wrong.

My father also loved Dartmouth. Every car we ever owned was Dartmouth green; so was our house, after Dad convinced Mom that Mount Holyoke blue would look especially ghastly between the pink stucco and aqua brick abominations on either side of us. (This was the 1970s, after all, when people actually listened to John Denver and Helen Reddy LPs after dinner and reveled in painting their homes nauseous colors).

As far back as I can remember, my dad interviewed Dartmouth applicants in our living room, and I honestly can't recall a time when I wasn't pretty certain that I wanted to spend four years in Hanover. By an odd coincidence, I ended up living freshman year in the same corner of the same dorm, Lord Hall, where my dad had spent his freshman year. But I felt his influence there in other, less literal ways too: As a legacy, I sensed extra pressure to succeed, so I knocked myself out trying to excel. My dad would just roll his eyes when I told him all the things I was doing on campus, then wax lyrical about how women had bettered the place and how the breed must improve. I bet he's already ordered '14, '16 and '17 Dartmouth sweatshirts for his granddaughters.

Interviewing your father is sort of like inviting your podiatrist to lunch. It's just an odd mixing of contexts, particularly since my dad has never told me a blasted thing I could use in a news story. My instinct to charm, browbeat or pressgang people for information and my dad's equal but opposite instinct to reveal absolutely nothing have become a family joke over the years. "Hey Dad, what's up with the K Street drug gang trial?" I might ask, innocently enough, at Thanksgiving dinner. "Now, off the record, Sarah," he'd reply sternly, glancing surreptitiously around the room as if scanning for hidden paparazzi, before imparting some truly mundane bit of information such as the trial date. I'm still not certain whether he believed this was a salacious tidbit or whether he was making fun of me and my media ilk, but I guess it didn't matter. Either way, he wasn't talking.

When I went to interview him in August, he wasn't interested in discussing the Microsoft case. In an unusual move, he'd spoken to reporters a few weeks earlier at the end of the trial and taken some heat for it—although, again, his comments about the case were utterly banal. He was, however, quite happy to talk about Dartmouth and his own plans for the future. And to tell his favorite judge joke.

When did you first know that you wanted to be a judge?

Probably while I was at Dartmouth. During one exercise we did for a government class, I was asked to preside over a moot trial. And it came very naturally. I thought that if ever there were a career that suited my temperament, this was it. Thinking realistically about it, though, I guess I realized I would like to be a judge when I encountered any number of judges during my career as a trial lawyer and formed rather strong convictions about what I thought represented the ideal trial judge.

I remember there were a few judges whomade you want to tear your hair out.

Yes, there were some, who shall remain rtameless. But there were others I thought were absolutely admirable people and held in the highest respect.

Which Supreme Court justices do youmost admire?

I admire anybody who has become a Supreme Court justice. It represents the culmination of what must have been an extremely distinguished career and a demonstration of obvious legal ability. I don't think there's any sitting justice who commands more of my admiration than anyone else. Certainly there are some past great justices whose abilities are recognized universally.John Marshall, our fourth chief justice, served for 35 years and was in effect the architect of the American democratic system. He defined all the various provisions of the Constitution with an almost uncanny clairvoyance with respect to what this country would ultimately become. There have been other great justices: Oliver Wendell Holmes, of course, is a name that immediately comes to mind; Benjamin Cardozo; Hugo Black.

You have been praised on both sides for the way you handled the Microsoft trial. What did you learn from the experience?

What I have learned is that it is physically possible to expedite a major antitrust case to a conclusion. Whether I have done it correctly remains to be seen. So I'm going to have to await the verdict of an appellate tribunal to see whether or not the various procedures I have implemented were appropriate in the circumstances. I do not want to try it again, however.

You've sparked some controversy by talking to the mediaabout the Microsoft case. Why did you give interviews?

As a general proposition, I do not talk to the press about my decisions. I allow my decisions as they are published to speak for themselves. In this case, I became somewhat alarmed at what I thought was a misperception of my role in the case, both favor- able and unfavorable. Those who were pleased by what I did regarded me as some sort of a Lone Ranger. And those who disapproved of my decision regarded me as a publicvillain.And I was given a role in at least some of the commentary that was inconsistent with the role that I actually occupy which is that of a federal district judge, whose job is to consider evidence and to make a decision. It was not open to me not to make a decision.

What are your thoughts about the media and their coverageof the high-profile cases in which you've been involved?

By and large, the coverage of the Microsoft trial was quite good. To the extent that I followed the stories in the major publications, it seemed to me that they understood the issues and the general significance of the testimony that was given. Again, however, I think that by and large they paid far too much attention to what they thought was my reaction to what was being said and [to my reaction] to the witnesses themselves. And they gave an import to questions that I would ask, for example, far in excess of any significance they had as a harbinger of my reaction to the testimony Believe it or not, I usually ask questions to inform myself. There was a time when I was a trial lawyer when I asked questions for effect. But that's not the proper role of a judge.

But the media were always saying, "He's going to throw thebook at Microsoft." And in the end you did throw the book atMicrosoft. So maybe they were right.

The decision was the product of the accumulation of all the evidence I heard. Some witnesses were more convincing than others.

Has anyone given you a hard time as a result of your havingspoken with the media about the case?

Yes. But I thought it was necessary. I don't intend to make a regular practice of it, but I felt it was necessary to add some clarification to what I thought was a public misperception of my role. The truth be told, I was reinforced in that conviction by the journalists to whom I spoke.

In what way?

I think that the questions that I was asked indicated that there was a basic misunderstanding of what I had done and why I had done it. I'm not suggesting that they neither read nor understood what I wrote in the way of opinions in the case, but I don't think that there was a general comprehension of the context.

I have read all the letters you received from the general publicabout the Microsoft case. My favorite was the letter that calledyou a "commie pinko pustule." Who wrote that?

I think that was anonymous. But it is not proper for me to consider ex parte communications, whether by correspondence or any other medium.

Have you read Bill Gates's book, The Road Ahead? No.

Do you intend to?

Not until the case is over, if ever.

What do you think the Supreme Court will do with theMicrosoft case?

I honestly don't know. It is my hope that they will take the case, and I hope they will affirm my decision. But I certainly have no insight as to what the Supreme Court will do. And if the Supreme Court decides that they would prefer to have it considered first by our Circuit Court of Appeals, so be it. I'm quite certain it will be ably considered by the Circuit Court of Appeals if they are the first appellate court to take a look at it.

Do you ever consider the historic import of your decisions,particularly of the Microsoft case?

I really don't. I leave that to other people who are better positioned to assess their significance. I simply try to do my job, which is to apply the law as I understand it to the facts as I find them to be. I think also that there has been a tendency on the part of the media to overemphasize the significance of my decision. My decision is the decision of a U.S. District Court—it's a trial court decision. Unless and until it receives the imprimatur of the Court of Appeals or at best the Supreme Court, it is simply the decision of one federal judge in one district.

Did you ever chat to Microsoft attorney Bill Neukom '64? If so, about what?

Yes, he was a regular member of the Microsoft trial team. We had no informal conversations, but Mr. Neukom was regularly in attendance when we held chambers conferences. And periodically there would be some casual mention of the Dartmouth connection. I recall that he was interested in seeing a photograph that I have on my wall of the one and only visit made by the Earl of Dartmouth in 1904 [to Hanover]. It was shortly after Dartmouth Hall had burned down, and efforts were being made to raise funds to reconstruct it.

Now a couple of questions about Dartmouth. It's changed alot since you were there. How do you feel about those changes,or do you even care any more?

I still feel a very close identification with the institution and believe that on balance everything that has occurred since I graduated has been for the benefit of the College. I think it is a stronger, healthier institution now than it was when I attended in the 1950s, and it was a wonderful college then. But it has matured with the changes in society and it has done so skillfully, and it has retained most of the best of the old Dartmouth while becoming a truly international university of premier stature.

Any classmates or professors you remember in particular? You used to talk about an old roommate named Reg who had a photographic memory that amazed you.

Sure. Reg Bartholomew '58 was my roommate for two years, and a fraternity brother for three. I've followed his career from a distance with admiration. Reg had a photographic memory. He was a thespian, and when he would take a role in a play he could read the play once and remember 90 percent of the dialogue. And on the second reading he was almost letter-perfect.

Anyone else?

Oh certainly, all my fraternity brothers. The fraternity was a very large part of my college experience. One of the current initiatives at the College is to modify the fraternity system, and I am watching the process with some concern that those things that were so congenial to me when I was there may not be retained. I hope that it is not altered so drastically as to eliminate those aspects of fraternity life that truly allowed members to feel that they had a home and a family away from home. I have to say that my fraternity was very much a straight-arrow fraternity. We didn't get into any trouble, and we usually stood first or second in all the intra-fraternity competitions, academic and otherwise. We were perhaps in the middle ranks as far as intra-fraternity athletics were concerned, but otherwise we were always a contender for the top spots. I remember all those men very very fondly and thought that the fraternity experience was an integral part of my college life. I also remember very fondly my colleagues in the NROTC program, many of whom I stay in touch with today. My fraternity was Delta Upsilon, by the way.

It's now a sorority.

I know.

What's the best lawyer or judge joke you've ever heard?

You know my duck joke.

Tell it again.

A law professor, a Court of Appeals judge and a district court trial judge go off on a duck-hunting trip together. They have a bet at the outset of the excursion that the first one to shoot a duck is going to win $100 from each of the other two hunters. However, if what is shot is not a duck, then the errant marksman is going to owe $100 to each of his fellows. And so they are sitting there in the gloom of the duckblind in the early cold, wet dawn, and the first bird flies over the horizon. And the law professor looks up and says, "Well, ornithologically it would appear to be a duck, and aerodynamically it flies like a duck." And he fires. But of course by this time the bird is long past. They wait awhile and the second bird comes over, and the Court of Appeals judge looks up and says, "Just last term the Supreme Court had a case which implied that if a bird were to appear at this time and at this place and at this season of the year it would probably be a duck, and there was a footnote as I recall in this case..." And he fires. But again the bird has disappeared over the horizon. A third bird comes over the horizon and the district judge looks up and fires, and the bird plummets into the water. And the district judge says, "I sure hope that was a duck."

Will you retire or take senior status when you turn 65?

My present plan is to take senior status and see whether or not continuing as a judge in a somewhat diminished capacity I will have the leisure time to do certain other things I want to do.

What activities do you have in mind, besides playing with yourgranddaughters?

Well, that of course is a major aspiration. But I would like to do some writing or maybe some lecturing. I might like to teach at St. Mary's College [in southern Maryland] or at least be a guest lecturer, as I have been invited to do this fall. I think probably I'd like to travel some more. I'd like to see Australia and New Zealand. Pat, my wife, would like to do a safari in Africa. And I would like to go back to visit some of the countries that I have not seen since I was in the Navy, like Greece and Italy. And having had one very favorable experience on a Dartmouth Alumni College Abroad trip to Russia, Id like to have an opportunity to do some of those.

So what do you wear under those robes? I hear the judges inHawaii wear Hawaiian shirts under their robes.

Nothing that interesting. A business suit.

Is it easier or harder to be interviewed by your daughter, asopposed to any other journalist?

Quite frankly, I'm intimidated.

The judge is "smart and wickedly funny," his daughter reports, "and somehow he manages never to hold a grudge."

MEN BEHAVING BADLY In Judge Jackson's higher-profile cases (clockwise from top left), he ordered the breakup of Microsoft, led by Bill Gates, earlier this year; sentenced Washington, D.C., mayor Marion Barry Jr. to six months in jail for cocaine possession in 1991; ordered Sen. Bob Packwood, R-Ore., to turn over damaging diaries in 1994 to the Senate Ethics Committee in its probe of sexual harassment charges; and fined former Reagan White House aide Michael Deaver $100,000 in 1997 for lying under oath.

"MY DAD HAS NEVER TOLD ME A BLASTED THING I COULD USE IN A NEWS STORY." SARAH JACKSON-HAN

"THE HAS BEEN A TENDENCY ON THE PART OF THE MEDIA TO OVEREMPHASIE THE SIGNIFICANCE OF MY DECISION."

SARAH JACKSON-HAN, a former executive editor of The Dartmouth, completed a master's degree as a Reynolds Scholar at Cambridge University in 1989. She covered Asian affairs for Agence France-Presse from 1990to 1999 in Washington and Hong Kong and now works as a writer andeditor at National Public Radio. She lives with her husband and two youngdaughters in Chevy Chase, Maryland.

The author of this story is donating her fee to the Karen Avenoso '88 Memorial Scholarship Fund, whose aim is to provide financial support to female undergraduates at Dartmouth who wish to become writers. Further donations may be sent to the Karen Avenoso '88 Memorial Scholarship Fund, c/o Stewardship Office, 63 S. Main St., Suite 6066, Hanover, NH 03755. For more information, click on www.avenoso.org.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAnd the Bride Wore Green

November | December 2000 By MEG SOMMERFELD ’90 -

Feature

FeaturePolitical Junkie

November | December 2000 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Feature

FeatureWISDOM OF THE GUIDES

November | December 2000 -

Feature

FeatureOVER-RATED

November | December 2000 -

Feature

FeatureWHAT STUDENTS SAY

November | December 2000 -

Feature

FeatureMEDIA MONSTER: The Rise of Rankings

November | December 2000

Features

-

Feature

FeatureAlumni Awards

JULY 1965 -

Feature

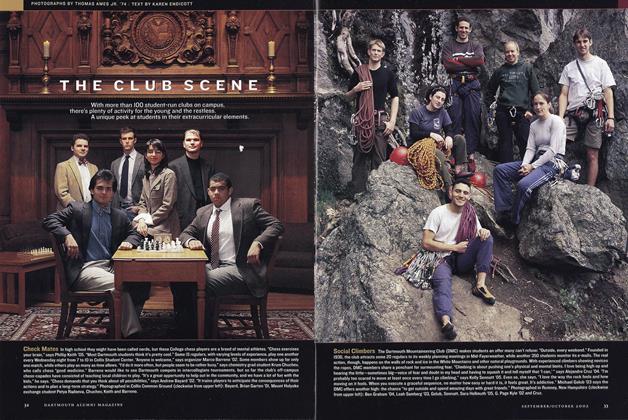

FeatureThe Club Scene

Sept/Oct 2002 -

FEATURE

FEATUREDramatically Different

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2016 By HEATHER SALERNO -

Feature

FeatureCenters of Excellence and the Survival of Creativity

APRIL 1984 By O. Ross Mclntyre '53 -

Feature

FeatureA China Perspective

OCTOBER • 1986 By President David T. McLaughlin '54 -

Feature

Feature'Far Out and Daring': Dartmouth Abroad

SEPTEMBER 1982 By Shelby Grantham