Student housing it ain't what it used to be (or is it?)

On campus . . .

In the beginning, the summer before the first-year students start their undergraduate careers, all 1,050 of them receive a general information brochure describing each of the College's 38 dormitories. They learn, first of all, that exactly half of them now include both men and women behind their doors. Some, like Butterfield and Middle Fayerweather, have all-male and all-female floors; others, such as French and McLane Halls, are divided by sections; and some, Middle Massachusetts for one, are divided room by room. There are eight all-male dorms, some with old traditions intact, and three all-female residences. (Lest the incoming first-year students and their parents - worry too much about coed bathrooms, the brochure makes it quite clear that separate bathrooms and showers are provided for each sex. Some halls have private baths for each room; others merely have separate ones, at each end of the hall.)

Dormitory size varies enormously, though the College is far from having any of the sky-rise halls often found at urban schools. Coed Topliff, located near Alumni Gymnasium on East Wheelock Street, captures the dubious honor of being the largest dorm; it contains 179 inhabitants. Russell Sage is second with about 50 less. If one excludes the fraternities and the eight residence units open only to upperclass students, all-male North Hall is the College's smallest dormitory, with a paltry 22 residents.

The cost of dorm housing does not vary substantially: of the 2,666 dorm residents this fall, over 2,400 paid rents of between $465 and $520 per ten-week term. The remainder pay rents on either side, and costs can range as high as $573/term for the highly-desirable upperclass apartment residences of Channing Cox and Courtside. After turning in preference cards that list choices for single-sex or coed, location, and number of roommates desired (if any), the incoming class then waits for housing assignments.

Soon after Labor Day, as the first-year students enter their rooms for the first time, they are all met by basically the same things: light walls, tile floors, bureaus, desks, beds, and (usually) roommates. Doubles are often one room, triples two, and any incoming student lucky enough to receive a single rarely gets one much bigger than a closet. Parents and older siblings have made sure that the 'shmen and 'shwomen have carted curtains, reading lights, sheets, blankets, pillows, and posters with them to Hanover. Some things, such as stereos and refrigerators can be borrowed or rented from others going offcampus. Posters and wall hangings can be found "downtown" at reasonable prices. Though carpeting is not generally provided, worn-out, beer-stained rugs usually find their ways into just about every room before year's end, passed on to another class by the previous year's seniors and by those moving into fraternities or headed off-campus during the year. The College does provide, however, horribly designed lounge chairs, one per person. Perhaps they are a means of assuring students spend lots of time outside, for these chairs are obviously designed for someone with a normal upper body but the legs of an N.B.A. forward.

The most commonly-heard complaint about the dorms affects freshmen hardly at all that of limited cooking facilities. Since all first-year students are required to purchase meal contracts from Thayer Dining Hall for the entire year, their need for a stove is rare. But for upperclass students who want the flexibility of hours and menus that dorm cooking provides, the situation verges on desperate. The dozen or so stoves located "up campus" (a term that excludes the dorms now located behind Webster Avenue and behind the Tuck School) are not nearly enough. In order to cook, students often must travel down three flights of stairs and over hill and dale carrying pots, pans, and food a Herculean labor even when it's not raining, snowing, or blowing. There always seem to be 50 other people who want to use a stove when you do, and they are often not very clean or polite about doing so. Toaster ovens and hot plates are officially prohibited in the dorms, but the frustration of waiting in line for a stove tempts to their purchase and concealment. It is necessary, though, to remember to turn off most of the lights and temporarily unplug the fridge, or the room may well be plunged into darkness due to circuit overload.

Over half the dormitory residents — usually around 60 per cent - are upperclass students. In all dorms, specific undergraduate advisers (called U.G. A.s) help the incoming students adjust to the College and the dorm. These U.G.A.s introduce the first-year students to each other, plan group dinners and meetings, and later introduce them to upperclass students. Since the advisers are residents of the same dorm, they can help with various problems and questions through the new student's first two terms. Other dormmates are also usually quite willing to give advice less formally, spouting words of wisdom about avoiding certain professors, never taking a class before ten in the morning, and pouring beer from a keg the right way.

The College living arrangement most familiar to most alumni is doubtless the all-male dormitory, and the traditionalists will be glad to know that within the masculine bastions of South Massachusetts Hall and Richardson Hall, upperclassmen still invoke the old partying legacy. Ironically, few of any dorm's current residents are sure just how old these "legendary" punches and parties are. Bob Duncanson '83, a two-year resident of South Mass who is now president of Phi Delta fraternity, points to the "College Bowl" as his former dorm's strongest tradition. Patterned after a television game show, panels of upperclassmen students and pea-greens compete against each other answering questions about sports, dorm trivia, or whatever.

The composition of the panels switches every three or four questions, so that by the end of the night, just about all of the dorm's 69 residents have had a chance on the panels. A correct answer earns a team 20 points, as does a four-man team that "chugs" a beer. Chugging, or gulping down a beer at a single draught, is "a good way to keep up the pace," Duncanson advises would-be competitors. Later in the game, the points are doubled, and the "team boot bonus" is sometimes invoked. To collect the 100-point bonus, each member of the four-man panel must stagger up on a platform and regurgitate ("boot") - without missing, mind you into a nearby garbage can.

Reflecting on this annual ritual of South Mass, Duncanson said he feels it may be a "rude awakening" to some freshmen. He, along with most of the campus, considers his dorm rowdier than most, noting that each incoming class is introduced to "immediate kegs, beer pong, and chugging." South Mass is "an easy step into the fraternity system," the Phi Delt president said, pointing out that some 25 of the dorm's 29 freshmen his first year here joined one house or another.

A more moderate all-male dorm is Richardson, which, according to resident Peter Blum '85, is "one of the few exceptions to the assertion in the Committee on Undergraduate Life report that dorms don't provide an alternative to fraternities." This dorm, the College's oldest, is also one of its smaller, with 76 residents. It boasts a number of fireplaces a very popular drawing card after one's first winter up this way. Blum is not alone, apparently, in his feelings about Richardson. He notes that "more people return to it throughout their four years than to any other dorm I know." Richardson has an especially high dorm spirit, often manifested in the red-shirted horde of "rapiers" that charges to the sites of the dorm's intramural encounters in which Richardson is more often than not successful. Blum boasts of victories last year in innertube water polo and track, and a second place finish in intramural football, the premier event for dorm sports.

Behind the Tuck School is the River Cluster French, Hinman, and McLane Halls reputedly the least desirable housing on campus. Some rooms go unfilled until late in the term and exchange students are usually housed there. To counter the negative image among more permanent residents, the College has gone out of its way to provide for River Cluster students, by setting up study areas and ping pong and pool rooms and arranging for the River Cluster Formal, video movies, milk-and-cookie study breaks, and cider-and-donut parties before football games. Ironically, it hasn't made much difference to the reputation of the cluster but many of these ideas are being carried up campus, and numerous dorms now stage bagel breakfasts, study breaks, and formals.

Senior Evalyn Kragh '83, who lives in the all-female section of McLane Hall, likes the single-sex setting. After stints in the two popular coed dorms, Wheeler and Mid-Fayerweather, she appreciates the added quiet found in the River Cluster dormitories. "There is not so much commotion here," she says, noting that she "can go home and relax" at the end of the day.

Another set of dorms with a similarly unpopular reputation is the Choate Complex: Bissel, Brown, Cohen, and Little. The complex, like the River Cluster, has this reputation because of its distance from the center of campus, though it's a relative matter (anything more than a few hundred yards here is seen as an intolerable distance, especially in the winter): the Choates are right behind Webster Avenue. Residents of these dorms are also treated to special incentives aimed at creating a real community among the complex's 300 residents. Besides a schedule of educational and social events, the Choates also have large lounges, movies, and special study rooms. They have a coffee house and even a piano or two in the lounges. Dave Roberts, a senior and a three-year resident of Little Hall, served as Choate coordinator and as a member of the Choate Council, positions from which he helped plan many of the four dorms' activities. The Choates host faculty-student potluck dinners, cider-and-donut parties and lectures and sometimes even run a grill into the evening. Roberts adds that the Choates very seldom use liquor at their functions, for they are prohibited from using Council funds for that purpose.

"A lot of people get the impression that the Choates are a bad place to live, and tell the rest of the campus, that they are 'stuck' there," Roberts complained, but he said that most people who don't like the Choates have never lived there. Special to Roberts were the professor-student dinners. "I don't know any other way for a first-year student to have dinner with a faculty member and get to talk to him in that type of setting."

But not all residents of the Choates are as positive as Roberts. Robert "Wiz" Banks '84 has been there since freshman fall, except for a stint in Wheeler, and he is very unhappy with his present dorm location and with his room. "The cinderblocks seem to crowd me in. The rooms themselves are very unpleasant," he said. But he does agree with Roberts that fellow residents are nice. "I've made some good friends in the Choates," he said.

Across the campus, near Alumni Gymnasium, stands ToplifFHall, home of 179 undergraduates, one of whom is Beth Hovey '83. The senior finds that in Topliff solidarity is a matter of separate halls or floors, not of the building as a whole. Though most .of the first-year students are shunted into doubles, upperclass students often have the option of taking singles. For Beth, living in a single is particularly appealing. "The decision to remain alone or be with others can be made on an individual, moment-to-moment basis, not on the whims of roommates," she said. Topliff, which is coed by wing in parts and by room in other parts, has a drawback in the large number of people who move in and out each term, Hovey says, and she cornplained of discontinuity in the dorm.

Elise Miller 'B5, a sophomore from Butterfield Hall, feels that dorm solidarity is not a necessary part of living on-campus. "My best friends live in other dorms, so I don't hang out at all," she said. Elise, who has a single in this coed dorm of 59 residents, is a member of Kappa Kappa Gamma sorority and is an editor at The Dartmouth. "Sometimes I look at my dorm as little more than a place to sleep," she said.

Chris Anderson 'B5 is a sophomore from Middle Fayerweather, a large, older brick-and-granite dorm behind Dartmouth Hall. He finds dorm solidarity an important part of his decision to remain on campus: "Most students return to Fayer for all four years, and those who do move out usually maintain a continuing alliance with the dorm and its residents," he said. Anderson, not a member of any fraternity, notes that the dorm's distance from Webster Avenue discourages frequent trips to fraternity basements: "When the diehards become thirsty, it is more appealing to get a keg and set it in the hall than to make the long, cold trip across campus."

During an undergraduate's final three years, the living options multiply. Once a sophomore, he or she may choose fraternity housing, an apartment off-campus, affinity housing (such as the International Students House and the AfroAmerican and Native American houses), or another dormitory. Approximately twothirds of the students choose to return to dormitories whenever they are enrolled in Hanover-based courses. This fall, there are 1,620 upperclass students in the residence halls and 336 living ofF-campus. The fraternities house another 288 students not included in dorm housing statistics. Though a number of dorm residents are biding their time waiting to move into the frats or off the campus, many others appreciate being on the campus, close to classes and other students. They appreciate being part of the large communities that are their resident halls.

On-campus living offers other conveniences, too. Unless off-campus apartments are crowded ones, dorm rooms are usually cheaper, especially if heat and electric bills are taken into account. Finding reasonably-priced apartments in Hanover, within walking distance of the campus, is not an easy task. Even if a house or room can be found, the problems multiply. Because students are coming and going every ten weeks, hanging onto a desirable apartment for a year by juggling occupants can be quite a bother. And there are all those additional bills: light, heat, and phone, for starters. For many, the difficulties outweigh the dormitories' lack of cooking facilities and lack of privacy, and more often than not, upperclass students set down their belongings in one of the campus's many dormitories. S.F.

. . . and off

ee whiz," sighs Debbie Dartmouth, "I haven't seen Carol College in terms and terms! It's been ages since we lived together in Mid-Fayer-weather, and now I'm heading off to Kicking Horse, Montana, for a Tucker internship, and she's going to Edinburgh to study philosophy. We'll both be on for the spring and summer terms, though. I'd really like to spend a lot of time with her then."

Debbie and Carol go to the housing office to see about sharing a room on-campus, but alas, alack! according to the housing office's "priority" system, Carol's privileges are in Woodward and Debbie's are in Mid-Mass! The only place that they can live together on-campus seems to be the River Cluster, and that will never do! Carol and Debbie walk out, downcast and dejected. They head for Collis to discuss their plight over coffee; by the third cup, they have decided to move off-campus.

Carol and Debbie invite Brittany Beansprout to join them in their endeavor, partly because they like her and partly because she'll be at Dartmouth during the winter term and can look for an apartment or house in Hanover. Brittany has her own reasons for wanting to live off-campus. She had looked forward to dormitory living and had used great care in choosing an allfemale dormitory for her first year. She found, though, that its "sorority stereotype" was overpowering. On an April night, for example, she looked up from her desk in the study room of her dormitory to realize that the building was deathly quiet everyone, it seemed, was at a sorority rush event. That had hit home. She felt like a pair of blue jeans in a sea of Fair Isle sweaters. It was time to move out.

Brittany knows Debbie and Carol from singing in the Glee Club. She doesn't know them very well, but she likes them, and she is desperate to get off-campus. In addition to the freedom of independent living she anticipates, she wants to be able to cook her own meals: Thayer food made her gain fifteen pounds during her first year, and the Collis Cafe is just too expensive. Most importantly, though, she wants to live in an environment that she can make into her own home. So, Brittany signs on. Even if the three women don't get along perfectly, she decides, they'll harmonize.

Brittany's first step toward finding a place to live is a visit to Kiewit Computation Center, where she runs off a program called "Old Rentlib." "Rentlib" is a listing of off-campus openings in the Hanover area, divided into categories of furnished and unfurnished houses, furnished and unfurnished apartments, and rooms in occupied houses. The program, if you want to list all of the categories, takes about forty minutes to run off, so Brittany wisely brings her knitting with her. In the end, however, she is disappointed to find that only three or four of the hundreds of listings sound appropriate. Most are not within walking distance of the campus, and none of the three women will have a car.

But Brittany remains undaunted; she goes home (to her dormitory) and starts telephoning the landlords who sound likely. One tells her that the rent for his house is $300 per person each month, plus heating expenses, and another will rent only for a full year. Another, after failing to return eight of Brittany's calls, informs her angrily that he does not rent to students. (He pronounces "students" as if he means a lower form of life.) A fourth agrees to show Brittany his house, located near Thompson Arena, but she finds it to be virtually uninhabitable. (Well, that's not exactly true: a family of skunks seems to be doing quite well on the second floor.) The windows are broken and the floor sags suspiciously. Strike four.

Brittany retreats to Collis to drown her angst in hot cider. At the next table, she overhears a conversation between her acquaintances Fred Fraternity and Otto Outing-Club. Otto, it seems, has just won a grant from the Outdoor Affairs committee to study crocodile activity in Florida but he can't decide whether to take it. It would mean changing his D-plan, parting with his girlfriend, subletting his off-campus house. ...

Brittany waits no further (after all, she's an aggressive Dartmouth woman and knows when opportunity is knocking). She acquaints Otto with her situation and asks if she, Debbie, and Carol might rent his house while he is in Florida. Otto thanks her for her interest and says that he'll keep it in mind, but that he does not know what decision he will make.

The weeks pass. Brittany, Carol, and Debbie write Frantic letters to each other: Finally, just before winter-term exams, Otto decides that he would rather spend his spring with crocodiles than with his girlfriend (who has left him, anyway, for a Franqais she met on L.S.A.). He drops a note to Brittany in the campus mail saying that if she still wants the house known intriguingly as "The Space Shuttle" it's hers.

And that's how it happens.

There are many ways to live off-campus at Dartmouth, and many reasons for making the move away from dormitory life. Dartmouth students have lived in tents, teepees, trailers, and log cabins, as well as in the more traditional apartments and houses, some of which carry extraordinary nicknames "The Blue Zoo," "The Dog Patch," "Le Bateau Lavoir," and "The Celestial Bunny" among them. Several of these are passed down each term from student group to student group; others are temporarily loaned to favorite students by Dartmouth professors on sabbatical.

This fall, approximately one tenth of the Dartmouth students taking classes in Hanover lived off-campus, most of them in apartments and houses in Hanover, some in the neighboring towns of Thetford, Norwich, Lyme, and Etna. On the average, students can expect to pay around $200 per person per month for a share in a house, exclusive of heating costs (which, given the latitude, can add a hefty amount to the monthly bill). Landlords run the spectrum from the sublime to the malevolent, and several have such bad reputations that only the most desperate students will trust them. Few landlords will rent for single-term periods, but students often accept the year-long leases, confident that they will have little trouble finding sublessees for the terms they plan to spend away from Dartmouth.

Off-campus living offers an entirely different lifestyle from that found in dormitories primarily the opportunity to make a more stable "home" at College. It's an addictive way of life, and very few of the students who make the move off-campus manage to make it back on. It can also be a lesson in real life pipes that burst, landlords who disappear the same week as the heat, rent checks, messes which no dormitory custodian will clean up lessons which may certainly come in handy later on. And the pleasure of inviting friends "over to my place" is something that cannot be matched in dormitory living no matter how cozy one has made his or her dorm room.

The moral of our little fable is that, for many of us, the pleasures of off-campus living outweigh the pains. There is no question that housing is tight in Hanover - any Dartmouth student who finds a pleasant, reasonably-priced situation within walking distance of campus has had the luck of Ali Baba - but for those who persevere, the rewards are sweet. Let's hope that Debbie, Carol, and Brittany find it so, too. J.K.

All-male South Massachusetts Hall is one of the remaining "masculine bastions."

The decor in Wheeler Hall ranges from the demure to the Dantesque.

The house at 19-A Maple Street in Hanover has been handed down through generations ofDartmouth students.

Off-campus housing is sometimes far-flung. "The Celestial Bunny," a farmhouse in East Thetford,Vermont, is home to four Dartmouth undergraduates.

Steve Farnsworth 'B3 and)ean Korelitz '83 arethis year's undergraduate interns at the MAGAZINE. He lives on-campus, in a dorm, and shelives off, in a shared house.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOn Building Community

December 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

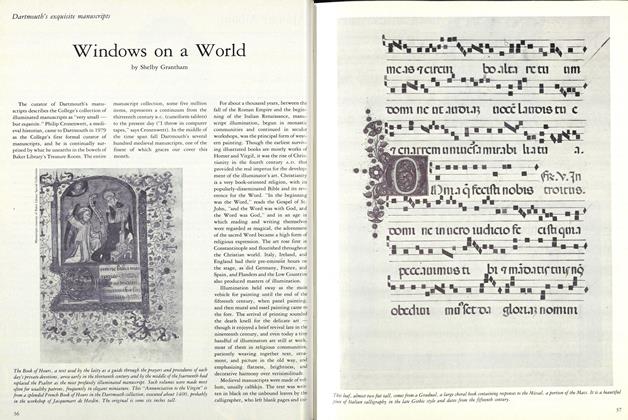

FeatureWindows on a World

December 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Article

ArticleDartmouth in the World

December 1982 -

Article

ArticleRound the Girdled Earth...

December 1982 -

Article

ArticleTHE DICKEY ENDOWMENT

December 1982 -

Article

ArticleOff to a Good Start.

December 1982 By Bernard D. Nossiter '47

Features

-

Feature

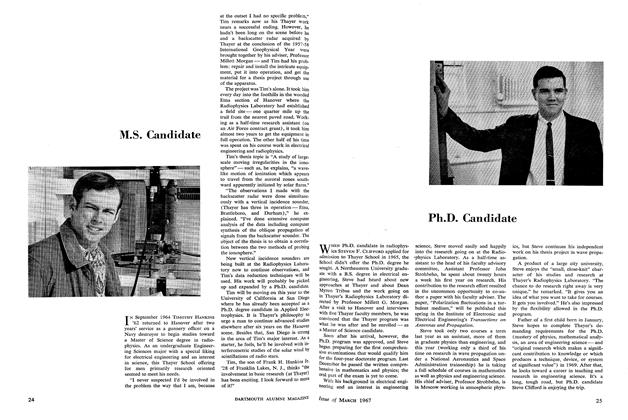

FeaturePh.D. Candidate

MARCH 1967 -

Feature

FeatureJAMES DORSEY

Nov - Dec -

Feature

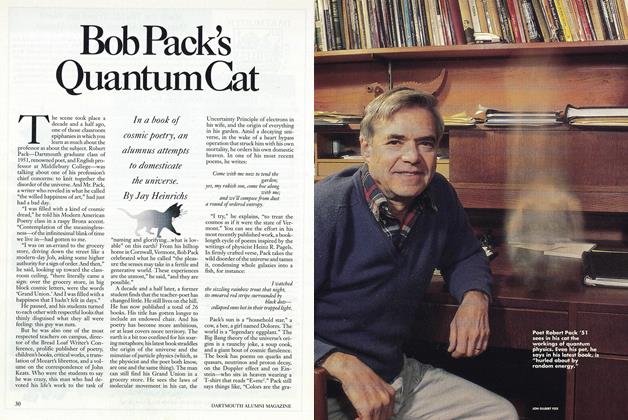

FeatureBob Pack's Quantum Cat

December 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureVoices in the Wilderness

May/June 2001 By Jennifer Kay '01 -

Feature

FeatureOur Place in the Sky

November 1959 By PROF. MILLETT G. MORGAN -

Feature

FeatureGolden Memories

May/June 2012 By SARAH SCHEWE ’12