The tube isn't a vast wasteland if you know how to watch.

Striding to the television in his Wilson Hall classroom, film studies professor Mark Williams wonders aloud: "How many times have you come home to an empty house and immediately flicked on the TV? What's that about?" Then, caressing the tube, he suggests, "It's always there for you."

Yes, it's TV studies, the exciting new course where students tune in without tuning out. Couch potatoes beware. Williams's course, "Television: A Critical Approach," asks students to confront one of the hardest exercises in critical thinking: taking a fresh look at the familiar.

We all know that television is one of the most familiar aspects of contemporary life. In the United States alone, televisions populate some 98 percent of households. Around the globe viewers rack up 3.5 billion hours in televisual glow. It doesn't take an advertiser to know that television is the most influential medium of modern times. Yet it's only recently that television has been formally studied. "How can we ignore it?" Williams asks, and, in a comment the young cartoon-philosopher Lisa Simpson would be at home making, adds, "One could argue that the printing press is more important...."

It's precisely the printing press's most ardent fans including, as you might expect, a host of academics who tend to write off television. "People assume it's simplistic, nonsensical, stupid," says Williams, whose doctoral research was on early TV in Los Angeles. "Sure, not everything is good on TV, but that's true of other media." Rather than ignore television, he asserts, we should view it with as sharp a critical eye as we use for literature and other expressive modes. In fact, nearly all critical approaches, from Marxism to postmodernism, can be used to probe how television does what it does. (Take MTV. It's the ultimate Marxist nightmare "the ads are the show," says Williams. A swirl of genre, form, and references, MTV is also the quintessential postmodern foray into televisionland.) Under such scrutiny even the widespread tendency to dismiss television is instructive. Says Williams who jokes that whenever he's watching TV he's doing research "One reason television is so powerful is that people don't take it seriously."

Until recently, even the field of film studies tended to look down on television as the litle screen that couldn't. Forgetting that the intelligentsia used to scorn films, screen theorists of the 1970s contended that the specialized, dark theatrical setting, largescreen spectatorship, and narrative integrity of movies drew audiences into the experience in a way that television shows studded with commercial breaks and beamed to small screens in private living roomsnever could. Screen theorists my opically argued that the swirl of home life surrounding TV meant that television could never be more than a distraction glanced from behind an ironing board or a newspaper. Moreover, says Williams, who also teaches film studies, film theorists narrowly insisted that because television does some things, it can't do others: it can only be fun and silly, therefore it can't be serious, wellwritten, or artistic.

Television studies arose in the 1980s largely as a response against the overgeneralizations of screen theory. Feminists, noting that much of television seems to be aimed at women, took particular issue with the implication that television's aesthetics and social significance are necessarily "inferior." They pressed the point that television is polysemic, that it means many things simultaneously. Polysemic analyses investigated how gender, race, class, and other social categories shape assumptions about TV and viewers.

Soap operas, for example, are commonly regarded—and often dismissed as women's fare, and therefore different from the male bastions of sports and network news. According to Williams, it's easy to regard the redundancy and dispersal of soap narratives repeating the plot from the perspective of multiple characters as unique commentary on the lives of women, especially mothers, who constantly put other people's interests before their own. "But it's also important that much of the pleasure of soaps is anticipatory," says Williams. The more you watch, the more you get to know the individuals and care about their actions and reactions. It's kind of like getting to know Newt Gingrich or Hillary Clinton or the Dallas Cowboys, following their stories on the real-life soaps we call news and sports.

Williams's class soon grasps this point. "As guys reveal they watch soaps, it breaks down the gender lines we assume were there," he says. (Students also reveal that Friends has replaced Seinfeld as their favorite show—and that in class they are amazed to see the similarities between Seinfeld and the Burns and Allen Show, where stand-up comedy morphs into sit-com.)

One facet of television that Williams particularly likes to unpack in class is the notion of "liveness." Early television broadcast stagey vaudeville and dramatic presentations. Watching them was like being in the theater. Newscasts resembled on-air newspapers as announcers read stories from visible scripts, without the aid of graphics, save the teletype machine in the background. Liveness entered the picture in a big way in 1949, when Los Angeles's KTLA-TV covered the protracted attempt to rescue three-year-old Kathy Fiscus from an abandoned well. For 27 hours live television made an entire city take notice.

Live coverage has and hasn't come a long way since then, as the Jessica McClure and O.J. cases show. People still tune into the unfolding dramas and tragedies of breaking news. But liveness has evolved into various forms. News like the Gulf War comes neatly packaged, slicked up with logos and graphics, each network trying to outdo the other. As the "live on tape paradox suggests, the first showing of a so-called live event can occur after the event itself. Even replays of once-live coverage can be regarded as live in television's ever-present now. "Television has developed its own sense of time," Williams says. "Liveness is an important part of television's central goal: to be continuously alluring and available." It's TV's ultimate come-on.

Live or not, TV is not static. Television is protean, always changing, says Williams. That's part of what makes watching TV so easy and studying it so hard. Just when you think you understand it, someone goes and changes the channel.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

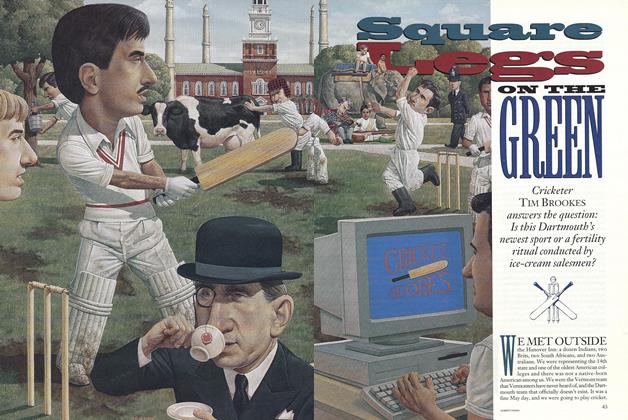

FeatureSquare Legs ON THE GREEN

April 1996 By ROBERTO PARADA -

Cover Story

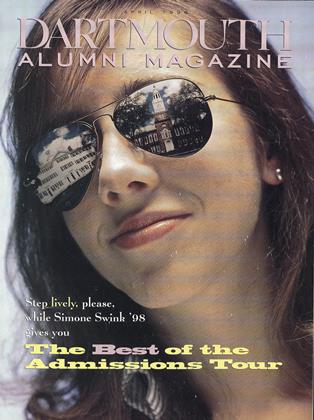

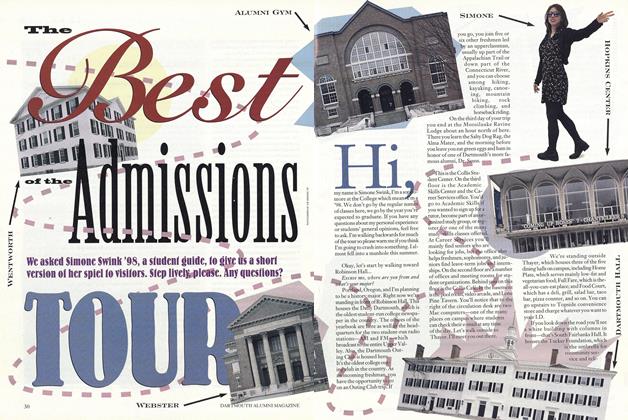

Cover StoryWe asked Simone Swink '98, a student guide, to give us a short version of her spiel io visifors. Step lively, please, Any questions?

April 1996 -

Feature

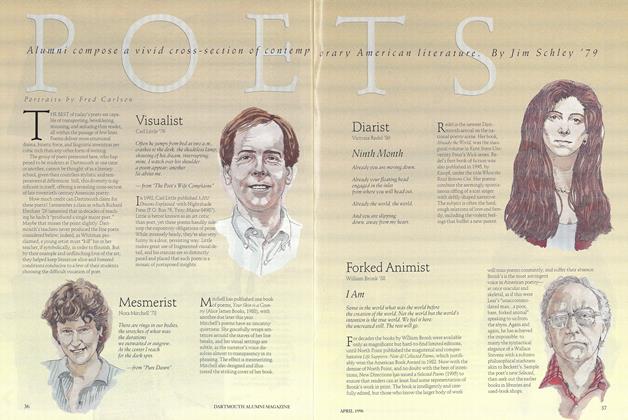

FeaturePOETS

April 1996 By Jim Schley '79 -

Article

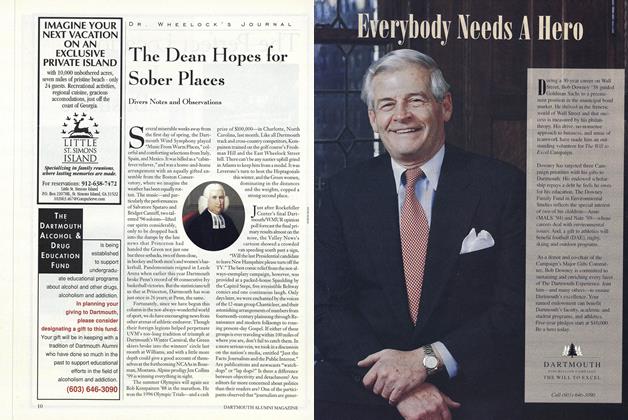

ArticleThe Dean Hopes for Sober Places

April 1996 By "E. WHEELOCK" -

Article

ArticleOh, Professor, No Charge for You

April 1996 By Noel Perrin -

Class Notes

Class Notes1971

April 1996 By Don O'Neill,