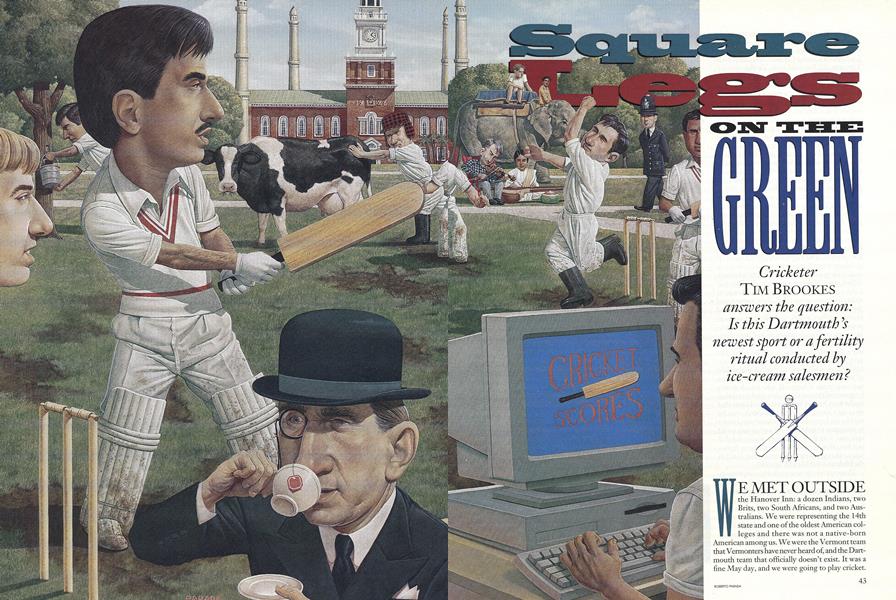

Cricketer TIM BROOKES answers the question: Is this Dartmouth's newest sport or a fertility ritual conducted by ice-cream salesmen?

WE MET OUTSIDE the Hanover Inn: a dozen Indians, two Brits, two South Africans, and two Australians. We were representing the 14th state and one of the oldest American colleges and there was not a native-born American among us. We were the Vermont team that Vermonters have never heard of, and the Dartmouth team that officially doesn't exist. It was a fine May day, and we were going to play cricket.

Standing around in white shirts, white sweaters, and white flannel trousers, we attracted some strange looks, but as the captain of the Chittenden County Cricket Club and the AllVermont XI, I'm used to it. To the outsider, cricket is a little—well, impenetrable. We've tried to raise funds by betting spectators that they can't figure out the rules of the game. Or any one rule. Or even whether this is a sport, rather than a fertility ritual conducted by ice-cream salesmen.

The terminology of the game doesn't help, reflecting, as it does, the delightful but cryptic English tradition of assuming that if someone 400 years ago in Yorkshire invented an utterly incomprehensible dialect-word for something, then that's what it should still be called. American sports have plain, utilitarian terminologies: Right Field. Left Field. Catcher. Pitcher. Tackle. Kicker. Cricket has fielding positions called square leg. Short square leg. Square short leg (all different positions, none of them implying a need for an orthopedic appliance). Silly midon and silly mid-off (don't make the joke that these positions are called silly because you'd have to be daft to field only ten feet away from the batsman. The English expect this naive etymology from Yanks, and smile patiently at you). Silly point (nothing to do with debating). Third man (Makes no sense at all. This guy fields at one end of the ground, so he should be either first man or last man). First, second, and third slips (actually a reference to greyhound racing, for Pete's sake: these fielders are supposed to crouch alertly like greyhounds straining to go, and before dog races had little starting gates they just had a line where the leashes were slipped. You knew you'd be sorry you asked, didn't you?). Cover point. Extra cover. Mid wicket, who does not stand in the middle of the wicket. The only name that makes the remotest sense is long-off, who stands such a long way off that on a good hot day he vanishes in the heat haze. I've played on grounds that were on a slope, so long-off couldn't even be seen by the batsman. Fielders have been known to volunteer to field long-off just so they could make out with their girlfriends during the dull patches. Mind you, what do you expect from a nation that gives its food names like Toad in the Hole and Bubble and Squeak?

Despite these arcana, cricket is a surprisingly hardy shrub, and has taken root all over the world. Games take place at all latitudes and in all climates: one game is played every Christmas between a Swiss team and an England team on a frozen lake in the Swiss Alps; another famous yearly fixture is played on a sandbar in the English Channel, the game lasting until the playing arena is submerged by the encroaching tide. Even we in New England have a famously eccentric game: every fall, as part of the Lake Champlain Islands Apple Festival, a team from the Chittenden County Cricket Club plays a team of Jamaican migrant apple-pickers on a small grass airstrip that runs through an orchard. If a plane wants to land during the game, we have to run off and wait under the trees.

The islanders of Trobriand, near New Guinea, learned the game from missionaries and from Australian fliers stationed there during World War 11, and have (perhaps correctly) interpreted it as a form of ritualized warfare: each team dances onto the field in formation wearing full decorative warpaint, and the bowler charges at the batsman and hurls the ball a stone like a spear. Who said this was a sissy game?

Earl Anthony's Ear

Cricket—the word probably derives from the Middle French cricce, or perhaps not, given that nobody really knows what cricce means is probably 600 years old. By the mid-eighteenth century, when it had become an organized club sport, it consisted of a bowler hurling a wooden ball at high speed along the ground (hence the term bowling) at a batsman, who was trying to use his wooden bat so skillfully that he not only prevented the ball from striking wooden stumps set up rather like a croquet hoop that he was guarding—his strike zone, so to speak but sent it skimming along the ground between a ring of crouching fielders or even over their heads into the nearest stream. From these squirearchical beginnings developed a game of infinite variety, which the poet Edmund Blunden aptly described as "that test/ Of Character and skill a thousand ways expressed."

"I think cricket is a lot more sophisticated and a lot more precise than baseball," Pankaj Dugar '94, one of the early Dartmouth cricket captains, said thoughtfully, though when pressed he admitted that he had only a passing knowledge of the older game's American cousin. "In baseball there are only about four or five different pitches, but in cricket there are so manyeveryone has his own specialty."

Partisanship aside, this is true. Cricket has more than twice as many ways to get out as baseball. Cricket takes place in the middle of an oval field rather than in the corner of a wedge-shaped one, so the batsman can guide the ball in any direction; there is no foul territory. Having a bat with a flat face four and a half inches wide helps him to find the gaps between the fielders and, by turning the wrists, to steer it downwards, reducing die risk of being caught. A batsman has probably two or three dozen different ways of hitting the ball.

The ball itself is a hard customer, about the size of a baseball but denser and with a single equatorial seam. The Dartmouth players can't use a proper ball when playing on the Green in case others nearby get hurt. "We take red insulating tape and tape it round a tennis ball, so it looks like a leather ball and it gives it stiffness," Dugar said. "It really does make a difference."

Instead of being thrown, this tough article must be delivered in a running catapult motion with a straight elbow, a legacy of the days when the ball was bowled underhand. Imagine Earl Anthony, dressed in white shirt and slacks, delivering a red field hockey ball from beside his ear rather than beside his knee, and you've got it exactly.

It's not surprising that Dartmouth has never successfully converted American-born students: the reflexes take a lot of rewiring. In Vermont, several Americans have taken up the game, most successfully as wicket-keeper (the equivalent of catcher) and batsman, though as the ball is played as it rises off the ground they find themselves using something more like a golf swing than a horizontal baseball swat.

War and Peace

Pankaj grew up in Bangalore, where he played for his school. In India, cricket is more than just a varsity sport, it's what soccer is to Brazilians an essential element in cognitive development. He played in his bedroom, using a cork ball and a drawer as a wicket. He often played on the streets. "The streets were a really good place to play cricket. Most youngsters in India who just play cricket as a recreation sport play on the streets with a tennis ball or a cork ball. Any time you play a match, it's the other extreme, it's very very formal. You always dress up in the proper tradition whites with the V-neck sweater, you have umpires, spectators, you have a captain who goes out for the toss, comes back and talks it over with the players."

His Radiant Countenance

What of cricket at Dartmouth? Official cricket clubs have large, hardbacked scorebooks that contain the scores of a generation of games in enough detail to overwhelm Roger Angell; official clubs have their scores in the local paper. Cricket is not—yet—an official sport at Dartmouth, and its history is, perhaps appropriately, maintained largely by oral tradition and memory (and e-mail, of which more in a moment). Pankaj believes that the game probably arrived on the Green after an unusually large influx of perhaps two dozen students from the Indian subcontinent in 1987. "My guess is that matches against other schools would have started in 1988. I've been playing cricket since I was a freshman, and when I arrived it seemed as if it had been going on for a while. Most players knew players from other schools, which were probably schools we've played during my stint at Dartmouth: Middlebury, UVM, Harvard, MIT, Columbia, and Bard."

The club has never had any official funding, but in 1991 a student brought back all the team's current equipment with him from India; it's now owned jointly by the team.

Estimates of how many games the team has played vary from eight to perhaps 15. It's not even clear whether the team has that most American of qualifications, a lifetime winning record. In September 1990, when Pankaj was a freshman, Dartmouth beat Harvard; in April 1993 the team beat both Middlebury and a combined Middlebury-Columbia team. In between, some games appear to have been less successful, and have deservedly been forgotten.

Cricket makes its appearance on the Green once the weather brightens up and the ground dries out. The word goes out over e-mail and Dartmouth's subcontinental students suddenly appear, collectively and visibly, as few as five or as many as 20, leaving the Frisbee players staring in bewilderment and surprise. Even Indian and Pakistani non-cricketers hang out, discovering to their amazement and delight that (to misquote Rupert Brooke) there is some corner of a foreign field that is forever Madras.

At this point it must be noted that there is a strange congruence among subcontinental Dartmouth students, electronic mail, and this centuries-old game. It's not simply that the Dartmouth players stay in touch by e-mail, or set up games with other college teams by e-mail. Given that the Valley News and Sports Illustrated are not known for ball-by-ball coverage of cricket, and given also that a great many subcontinental students have come to the United States to study sciences and are computer-happy, the Internet has become a cultural lifeline for the cricketer in voluntary exile.

"When I was at home I used to keep track of the matches being played, the Test matches, the one-day internationals, the bowlers, the batsmen, who's been added to the team, who's been dropped," Pankaj explained. "Over here, the Internet has a cricket news group, and that's how I keep in touch with what's happening in cricket. "

Cricket is being played up and down the median along the information superhighway, with messages zinging back and forth from MIT to the University of North Carolina to Microsoft Corp. to the University of Lahore, from Pakistan to Zambia to England, updating scores of major games almost hour by hour, bickering over whether this player should have been selected or that one dropped from the national team, inquiring about cricket history, rewriting cricket history, pleading for tickets to Test (i.e. international) matches or announcing satellite TV channels or shortwave radio frequencies where broadcasts can be found, debating the merits of the various commentators, grumbling about one hero's poor form or one umpire's poor eyesight—even a cricket poetry contest. Most days there are more e-mail bulletins about cricket than any other sport. Four-fifths of the postings are about the Indian or Pakistani team or their players.

Conventional communication runs top-down like a waterfall, obeying the gravity of the status quo, making it hard to reach laterally across a slightly alien society and find those who have the same minority purposes as you. In the United States, cricketers bypass the old fortresses of communication, with their clanking top-heavy presses and their pompous news anchors, by sending messages at the speed of light to addresses that don't even make sense to those above ground, exchanging hot flashes of information that would leave the sports editor scratching his head—names that utterly defy the ethnic traditions of the great sports of this great country: no DiMaggios or Rizzuttos, no Valenzuelas or Munozes, no Matuzaks or Brunanskis. Most cricketers have names that sounds like religious epic poems: Goonesekera, Arulanantham, Ramchandani, names that just by themselves could cause you to miss a deadline, and send Spellcheck into terminal infarction. The sports editor doesn't know what to make of cricket, so he makes fun of it or he makes as little of it as possible; he is not an enemy as much as a clumsy landlord from a different dimension. The e-mail cricketers have found their voices, and have found each other. This is fandom as it should be or perhaps as it will be, this is the electronic gossiping of the crowd up in the bleachers of the global stadium. This is the sign of a living sport.

Play Up, and Play the Game

It's one sign of life in this small but resilient shrub that in taking on the All-Vermont XI, Dartmouth was playing what might be its first game against a non-college side.

It must be admitted that the All-Vermont XI is a resounding title that all too often boils down to mean "all the half-decent players in Vermont who are available on that day, who with a bit of luck add up to 11There are perhaps 60 cricketers in Vermont, composing three and two halves cricket clubs, but on this particular day, late defections and widespread yard chores reduced this quorum to a dismal eight: seven men and a 14-year-old boy. The Dartmouth XI, meanwhile, consisted of only X—but cricket had been arranged, and cricket would be played, and only about an hour after the allotted time the two teams gathered on the field in Memorial Stadium.

Ah yes. The field. In cricket, unlike baseball, the ball is intended to bounce before it reaches the batsman. Ideally, then, the game should be played on a turf surface like a golf green, only flatter and with shorter grass—say, like a large pool table with a beer tent at one corner; an unpredictable bounce could be lethal.

"One game we played on the rugby field here was very interesting because it was very, very grassy with a completely, completely unpredictable bounce," Pankaj said. "Sometimes the ball would just be a grubber [one that runs along the ground like a grub], and sometimes it went right over your head. We had some pretty fast bowlers at that time, and the other team I think it was Columbia—they didn't. It was a good game, but two people got seriously injured. One person got very badly hit on the inner thigh—it was really black and blue, and he couldn't walk. The other was a '93, Chan Fonseka. The ball rose and hit him on the head. It sounded like when you knock something really hard with a piece ofwood. I thought his skull was gone, broken into many pieces. He just lay down for five minutes, and then he woke up, and he was, like, 'No, I'm fine.' As a matter of fact, he was hit not once, but twice! Just as hard. The second time was during a practice, I think. After that the games were considered incomplete until he got hit on the head."

A "sticky" wicket, that cliche of Noel Coward effeteness, is a playing surface that has been soddened by rain but is now drying. Under these circumstances, the captain of the fielding team will immediately bring on his fastest bowler who, at the international level, will bowl at more than 90 m.p.h. One ball will hit a soft patch and shoot straight along the ground making you jam your bat down quickly before it hits your stumps; the next will hit a drier patch and fly up at your face. Even if we do stop for tea and wear blazers off the field, cricket is not a sissy game.

The field in Memorial Stadium had been so abused by the cleats of thuggish football players that the grass huddled in scared little tufts in a background of baked dirt. The visiting team blanched a little, the two captains paced off a consensus 22 yards between the two sets of stumps, hammered the aforementioned stumps into the aforementioned baked dirt with a modicum of cursing and sweating, tossed a coin, and Dartmouth went in to bat.

Cricket is a cruel mistress. In the one-day version, each team only gets one innings [sic], so once a batsman is out, he's out for the day, and is usually reduced to wandering around the field or trying to chat up someone else's girlfriend. The first batsman was out almost immediately Leg Before Wicket the ball would have hit his stumps if it hadn't hit his foot first—to a ball that kept low. Given this and the uncertain bounce, the Dartmouth batsmen wisely played at first with extreme caution, as if expecting the ball to leap off the ground at right angles, or vanish down a rabbit hole and pop up elsewhere. After a few anxious moments, Dartmouth slowly realized that neither the pitch nor the bowlers were as dangerous as they had feared, and began to hit freely.

At once, the visiting team looked increasingly dismayed: this didn't even sound like cricket. Every cricket ground has its character, its idiosyncrasies, like the ground at Canterbury that for years had an oak tree growing within the boundary; if a fly ball ricocheted off a branch, a batsman could be caught out; if the ball got stuck up the tree, however, the batsmen could keep running until someone shinned up and got it. At Memorial Field the characteristic was acoustic: every well-struck ball produced a sharp report that echoed off the deserted metal bleachers with an unearthly clang. It was like playing with aluminum bats in the College World Series. In 30 years of playing cricket, I had never heard anything like it.

The day wore on, the visibly aging All-Vermont bowlers became steadily more erratic, and the ball pinged and clanged in all directions to the delight of the Dartmouth players, who had rather unsportingly set up a video camera. With the departure of Green batsmen a minor collapse took place, but the College still reached a daunting total of 187.

If the Dartmouth innings displayed the many and subtle variations in the contest between batsman and bowler, the All-Vermont innings showed the extraordinary symbiosis between the rules of cricket and the weather. (The game was, after all, an English invention.) Player after player scored a few runs, looked slightly more comfortable on the uneven playing surface, then got out. Two of the formerly youthful Vermont batsmen pulled muscles and required runners, a supplement that is rather more cumbersome than calling on a pinch-runner in baseball as both the batsman and the runner must be on the field. At one point four Vermonters were out at the wicket at the same time, all calling different instructions ("Wait! Run! Yes! No! Sorry!") to the consternation and confusion of all concerned.

In the end, the game was settled in the time-honored fashion: it began to rain. The Dartmouth team tried to cover the video camera and (more importantly) the scorebook. Bespectacled players wiped and squinted. It rained harder. It got darker. World War II pilots might have been able to fly in such murk, but they had been force-fed carrots. Finally the game was abandoned in legal circumstances that were as murky as the weather: Dartmouth could with a clear conscience claim the win; the Vermont players could equally persuasively claim that as the match was abandoned before their innings was over, even though they had mustered just 117 with only the last man and the boy left, the game was null and void, which was a pretty fair result for a team of eight, eh? Even if the honors were not exactly even, honor was satisfied. Cricket has a highly evolved sense of result that goes far beyond the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat, even though I, for one, having been hit in tender parts by sharply rising deliveries, was suffering the agony of the legs.

The Far Pavilions

Since that memorable day, the Dartmouth team and its semi-formal appearances on campus not only maintain the polycultural traditions of a college founded in part for Indians, but carry out the basic elements of a successful scholastic endeavor: to provoke and answer unusual questions.

It isn't easy, of course. These latitudes make for a short playing season, the bulk of which is obliterated by the scarcely populated summer term; Dartmouth can realistically play only between mid-April and the beginning of June, and mid-September and the first couple of weeks in mid-October. Still, both Middlebury and the University of Vermont have successfully launched and funded teams, which play an indoor version of the game through the endless winter. Then there's the shortage of equipment, and the lack of a properly prepared ground. But there's talk of raising the 30,000 rupees ($1,000) needed for equipment and shipping.

Cricketers are used to uncertainty; much of our formative adolescence is spent in cricket pavilions during rain delays, occasionally casting a judicious eye at the clouds, estimating how long it will take for the rain to stop, how long it will take the wicket to dry out. Nobody, but nobody, talks of calling the game off.

Mind you,what do you expect from a nation that gives its food names like Toad in the Hole and Bubble and Sqeak?

Even Indian and Pakistani non-cricketers hang out, discovering there is some corner of a foreign field that is forever Madras.

An unapologetic graduate of Oxford University, writer TIM BROOKES is the guy with the English accent on National Public Radio.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

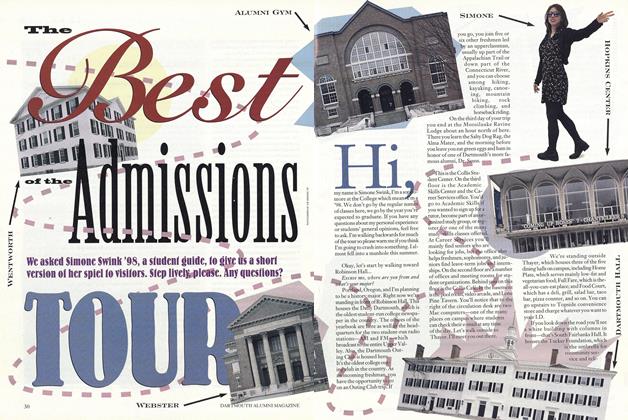

Cover Story

Cover StoryWe asked Simone Swink '98, a student guide, to give us a short version of her spiel io visifors. Step lively, please, Any questions?

April 1996 -

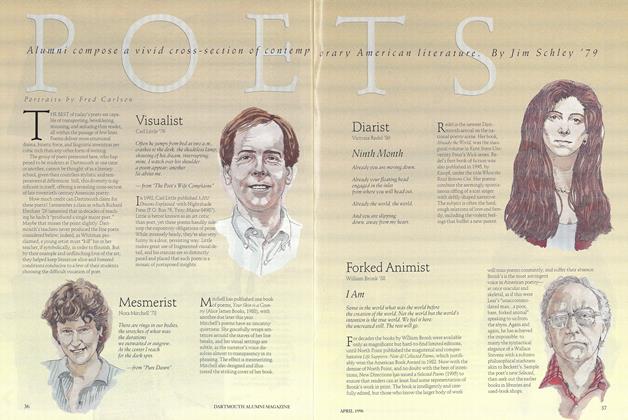

Feature

FeaturePOETS

April 1996 By Jim Schley '79 -

Article

ArticleThe Dean Hopes for Sober Places

April 1996 By "E. WHEELOCK" -

Article

ArticleTV Guy

April 1996 By Karen Kndicott -

Article

ArticleOh, Professor, No Charge for You

April 1996 By Noel Perrin -

Class Notes

Class Notes1971

April 1996 By Don O'Neill,

Features

-

Feature

FeatureEngineering Science 21

MARCH 1967 -

Feature

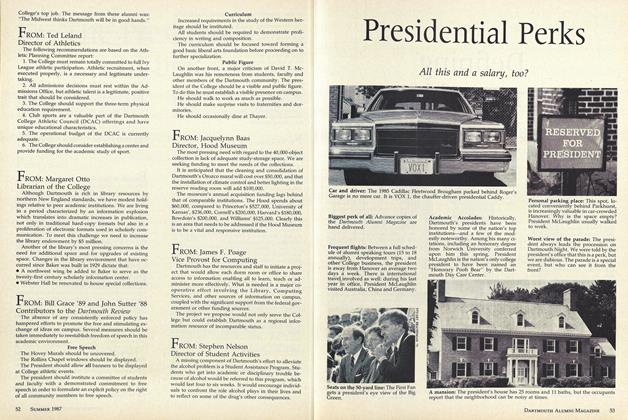

FeaturePresidential Perks

June 1987 -

Cover Story

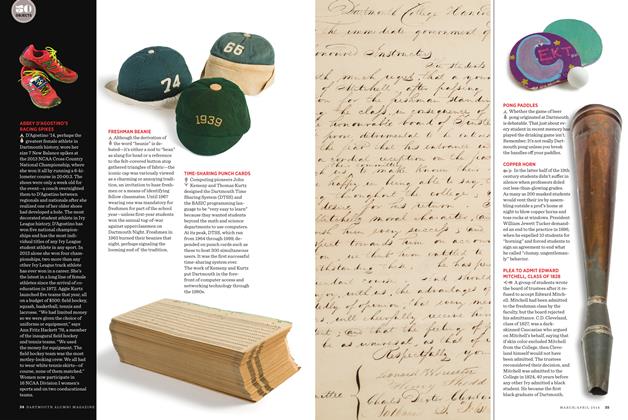

Cover StoryPONG PADDLES

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

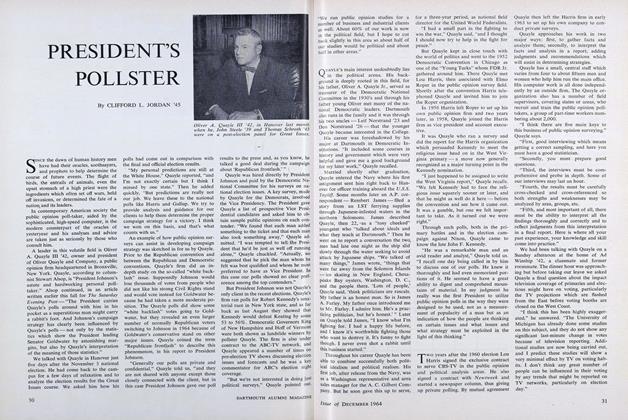

FeaturePRESIDENT'S POLLSTER

DECEMBER 1964 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeaturePublic Interest an The Technological Revolution

February 1955 By LLOYD V. BERKNER -

Feature

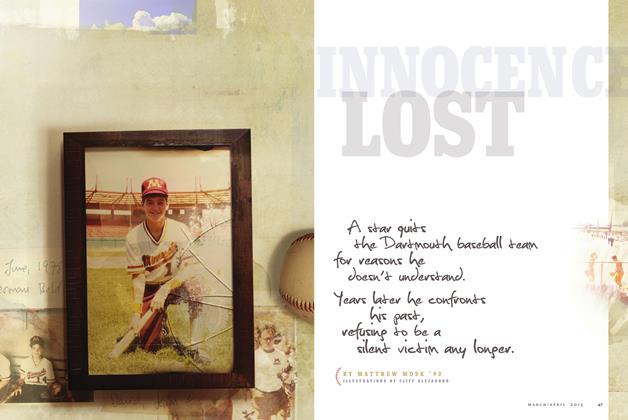

FeatureInnocence Lost

Mar/Apr 2013 By Matthew Mosk ’92