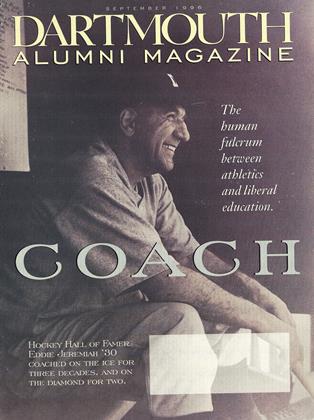

Coaches are often closer to students than faculty. It's a deep responsibility.

There are currently 61 coaches at Dartmouth. Football has the most: a head coach plus five full-time and six part-time assistants. Golf has the fewest: one coach for the men's team,one for the women's.

In addition to these regulars, there's also a fluctuating population of volunteers.Severalofthem are alumni with distinguished athletic records and some free afternoons; one is the owner of a local sporting goods store who volunteers his time in the evening.

I'm glad we have all these coaches. Well, glad in all ways but one. What pleases me most is the close friendship many coaches develop with students. I think I've been pretty close to some undergraduates, especially those who did an honors thesis with me, and some of those who took the small seminar I modestly called "How to Read Poetry."

But I never saw students daily, the way a coach does. I could never (with one glorious exception) schedule an extra class at an inconvenient time, and expect anything but shock and near-mutiny. Students often get up at dawn to practice, if a coach asks them to.

They also, I think,often take a coach's advice on life problems. Sooner, sometimes, than they will a faculty member's. Partly that's a matter of time and place. As every parent of a teenager knows, if you pickup your child at an airport and it's just the two of you driving home, the close quarters and the absence of eye contact sometimes produce confidences that would occur in few other circumstances. Trips to away games are among the few.

But partly it's that coaches often perceive the whole being of an undergraduate more than a purely cerebral faculty member might. I'm not attacking the faculty; we I have our own strengths. The College needs us all. But right now I am thinking about coaches.

What else are coaches good at? Oh, yes. They win games. No question, an able coach increases the number of victories a team wins, and a great coach increases it dramatically. We all like a winning team. (We're never all going to get them, of course, since any win for Coach X means a defeat for Coach Y. It's a zero-sum situation. Take all coaches away, and the full won-lost record would change not a whit.)

It's over this necessity of winning that I have my one problem with coaches. The pressure on them is too intense. A coach's very job, the welfare of his or her family, depends in part on winning. And you know what I wish? I wish that tight bond could be loosened a little.

Early Dartmouth football coaches had no financial stake whatsoever. For 11 years the undergraduate captain was also the coach. Sometimes he was aided by older volunteers, but the final decisions were his. And he didn't have to leave College if the team lost. Football player did not comprise his identity.

Or consider early Yale teams. Who coached them? Why, a man who worked in a clock factory in New Haven, five and a half days a week. He obviously couldn't be at practice every afternoon. No problem: His young wife (the sister of a famous Yale professor) ran the practices. Her presence is not something you hear about in the various official histories of football. In them Walter Camp coaches alone, and Alice Camp might not have existed. Of course the Camps cared whether Yale beat Harvard or Dartmouth, but neither of them depended on victory for a livelihood.

There is not the slightest chance that the College will go back to unpaid volunteer coaches, nor do I advocate it. What I do wish is this. I wish the typical coach were not exclusively a coach. Maybe he or she could coach part of the year, but also teach one course in one term, or do a little deaning. Maybe even take courses. There is precedent. The great John Heisman, he of the Heisman trophy, served as the football coach at Oberlin and did graduate work in art history simultaneously. Later he coached at Georgia Tech—and every summer he ran a theater, and acted in his own productions. Mostly Shakespeare.

That's all I want: coaches who are not entirely dependent on sports for their pay or their jobs, and who are thus exempt from some temptations once felt keenly at Harvard. In 1905, Bill Reid became the first paid football coach at Harvard he got the highest salary of any coach in the country, incidentally. Two consequences came along with Reid. Within six months, according to his biographer, he was practicing deception right and left. ("Chicanery" is the word his biographer uses.) And his players felt a new pressure. "It's not fun playing football under Reid," said one of them.

I'd like to keep a little fun, for coaches, players, and spectators.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

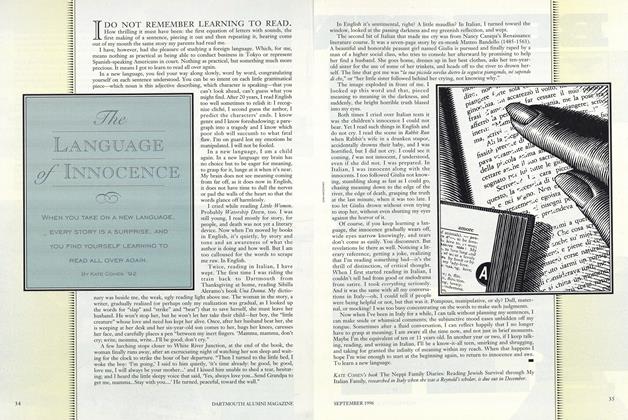

FeatureThe Language of Innocence

September 1996 By KATE COHEN '92 -

Cover Story

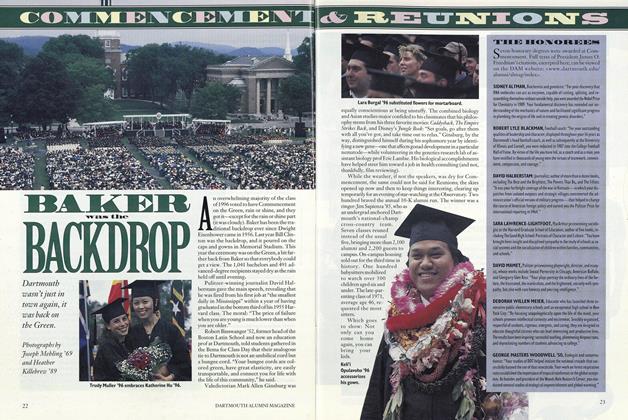

Cover StoryBAKER WAS THE BACKDROP

September 1996 -

Feature

FeatureStaying Clear

September 1996 By Jeanet Hardigg Irwin '80 -

Feature

FeaturePassion

September 1996 By Fiona Bayly '89 -

Feature

FeatureConfidence

September 1996 By Paid Tsongas '62 -

Feature

FeatureFaith

September 1996 By Seward, "Pat" Brewster '50

Noel Perrin

-

Feature

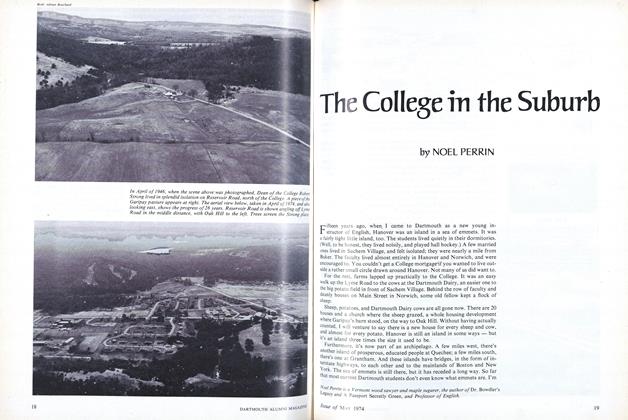

FeatureThe College in the Suburb

May 1974 By NOEL PERRIN -

Article

ArticleOffice Hours

JUNE 1996 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleEnvironmental Impact

SEPTEMBER 1997 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleOf Buses and Bells

May 1998 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleLooking for Frost

DECEMBER 1998 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleHow Green Is Dartmouth?

Sept/Oct 2003 By Noel Perrin

Article

-

Article

ArticleFORMER DARTMOUTH PROFESSOR KILLED IN THE EUROPEAN WAR

December, 1914 -

Article

ArticleThe Versatile Professor of Chemistry Known to the Dartmouth World as "Cheerless" or "L. B."

January 1936 -

Article

ArticleFaculty Articles

November 1949 -

Article

ArticleDevoted to Denver

May 1952 -

Article

ArticleA Wah Hoo Wah!

March 1955 -

Article

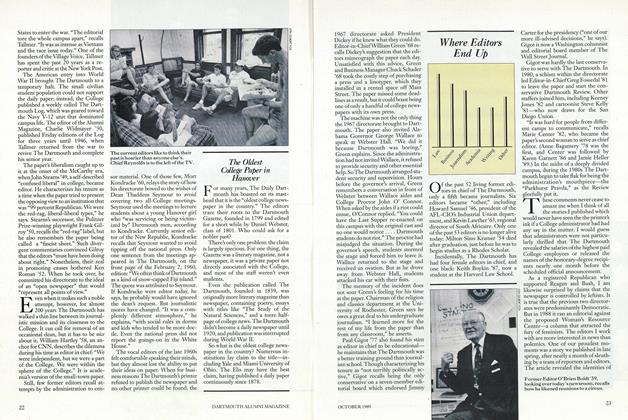

ArticleWhere Editors End Up

OCTOBER 1989