WHEN YOU TAKE ON A NEW LANGUAGE, EVERY STORY IS A SURPRISE, AND YOU FIND YOURSELF LEARNING TO READ ALL OVER AGAIN.

I DO NOT REMEMBER LEARNING TO READ.

How thrilling it must have been: the first equation of letters with sounds, the first making of a sentence, piecing it out and then repeating it, hearing come out of my mouth the same story my parents had read me.

I have, however, had the pleasure of studying a foreign language. Which, for me, means nothing as practical as being able to conduct business in Tokyo or represent Spanish-speaking Americans in court. Nothing as practical, but something much more precious. It means I got to learn to read all over again.

In a new language, you feel your way along slowly, word by word, congratulating yourself on each sentence understood. You can be so intent on each little grammatical piece which noun is this adjective describing, which character is speaking—that you can't look ahead, can't guess what you might find. After 20 years, I read English too well sometimes to relish it: I recognize cliche, I second guess the author, I predict the characters' ends. I know genre and I know foreshadowing; a paragraph into a tragedy and I know which poor slob will succumb to what fatal flaw. I'm on guard lest my emotions be manipulated. I will not be fooled.

In a new language, I am a child again. In a new language my brain has no choice but to be eager for meaning, to grasp for it, lunge at it when it's near. My brain does not see meaning coming from far off, as it does now in English, it does not have time to dull the nerves or pad the walls of the heart so that the words glance off harmlessly.

I cried while reading Little Women. Probably Watership Down, too. I was still young, I read mostly for story, for people, and death was not yet a literary device. Now when I'm moved by books in English, it's quietly, by story and tone and an awareness of what the author is doing and how well. But I am too calloused for the words to scrape me raw. In English.

Twice, reading in Italian, I have wept. The first time I was riding the train back to Dartmouth from Thanksgiving at home, reading Sibilla Aleramo's book Una Donna. My dictionary was beside me, the weak, ugly reading light above me. The woman in the story, a writer, gradually realized (or perhaps only my realization was gradual, as I looked up the words for "slap" and "strike" and "beat") that to save herself, she must leave her husband. He won't stop her, but he won't let her take their child her boy, the "little creature" whose love and need has kept her alive. Once, after her husband beat her, she is weeping at her desk and her six year old son comes to her, hugs her knees, caresses her face, and carefully places a pen "between my inert fingers. 'Mamma, mamma, don't cry; write, momma, write...I'll be good; don't cry."

A few lurching stops closer to White River Junction, at the end of the book, the woman finally runs away, after an excruciating night of watching her son sleep and waiting for the clock to strike the hour of her departure. "Then I turned to the little bed, I woke the boy: 'l'm going,' I said to him quiedy, 'it's time already: be good, be good, love me, I will always be your mother...' and I kissed him unable to shed a tear, hesitating; and I heard the little sleepy voice that said, 'Yes, always love you...Send Grandpa to get me, mamma...Stay with y0u....' He turned, peaceful, toward the wall."

In English it's sentimental, right? A little maudlin? In Italian, I turned toward the window, looked at the passing darkness and my greenish reflection, and wept.

The second bit of Italian that made me cry was from Nancy Canepa's Renaissance literature course. It was a seven page story by ex monk Matteo Bandello (1485-1561). A beautiful and honorable peasant girl named Giulia is pursued and finally raped by a man of a higher social class, who tries to console her afterward by promising to help her find a husband. She goes home, dresses up in her best clothes, asks her ten year old sister for the use of some of her trinkets, and heads off to the river to drown herself. The line that got me was "la sua picciola sorelia dietro la seguiva piangendo, ne sapendodi che," or "her little sister followed behind her crying, not knowing why."

The image exploded in front of me. I looked up this word and that, pieced meaning to meaning in the darkness, and suddenly, the bright horrible truth blazed into my eyes.

Both times I cried over Italian texts it was the children's innocence I could not bear. Yet I read such things in English and do not cry. I read the scene in Rabbit Run when Rabbit's wife in a drunken stupor, accidentally drowns their baby, and I was horrified, but I did not cry. I could see it coming, I was not innocent, I understood, even if she did not. I was prepared. In Italian, I was innocent along with the innocents. I too followed Giulia not knowing, stumbling along as fast as I could go, chasing meaning down to the edge of the river, the edge of death, grasping the truth at the last minute, when it was too late. I too let Giulia drown without even trying to stop her, without even shutting my eyes against the horror of it.

Of course, if you keep learning a language, the innocence gradually wears off, wide eyes narrow knowingly, and tears don't come as easily. You disconnect. But revelations lie there as well. Noticing a literary reference, getting a joke, realizing that I'm reading something bad—it's the thrill of distinction, of critical thought. When I first started reading in Italian, I couldn't tell bad from good or melodrama from satire. I took everything seriously. And it was the same with all my conversations in Italy—oh, I could tell if people were being helpful or not, but that was it. Pompous, manipulative, or sly? Dull, maternal, or mocking? I was too busy concentrating on the words to make such judgments.

Now when I've been in Italy for a while, I can talk without planning my sentences, I can make snide or whimsical comments; the subjunctive mood eases unbidden off my tongue. Sometimes after a fluid conversation, I can reflect happily that I no longer have to grasp at meaning; I am aware all the time now, and not just in brief moments. Maybe I'm the equivalent of ten or 11 years old. In another year or two, if I keep talking, reading, and writing in Italian, I'll be a know it all teen, smirking and shrugging, and taking for granted the infinity of meaning within my reach. When that happens I hope I'm wise enough to start at the beginning again, to return to innocence and awe. To learn a new language.

Kate Cohen'S book The Neppi Family Diaries: Reading Jewish Survival through My Italian Family, researched in Italy when she was a Reynold's scholar, is due out in December.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryBAKER WAS THE BACKDROP

September 1996 -

Feature

FeatureStaying Clear

September 1996 By Jeanet Hardigg Irwin '80 -

Feature

FeaturePassion

September 1996 By Fiona Bayly '89 -

Feature

FeatureConfidence

September 1996 By Paid Tsongas '62 -

Feature

FeatureFaith

September 1996 By Seward, "Pat" Brewster '50 -

Feature

FeatureChallenge

September 1996 By Colleen Sullivan Bartlett '79

KATE COHEN '92

Features

-

Feature

FeatureMay 17 Event to Salute Eleazar's Starting Point

MAY 1969 -

Feature

FeatureSnow Engineer

FEBRUARY 1972 -

Feature

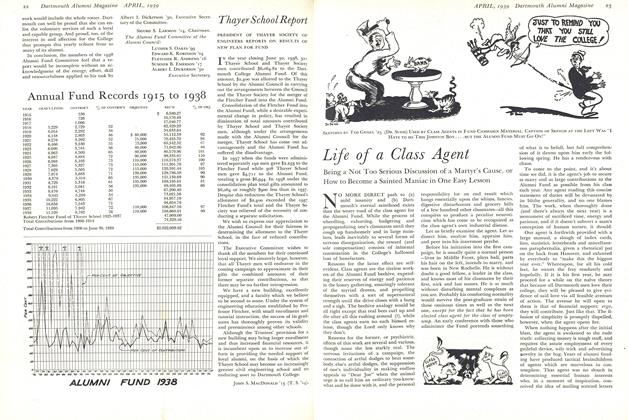

FeatureThayer School Report

April 1939 By John S. Macdonald '13 -

Feature

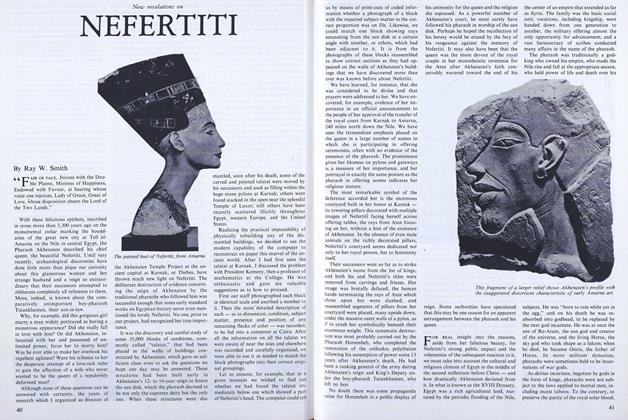

FeatureNEFERTITI

MARCH 1978 By Ray W. Smith -

Feature

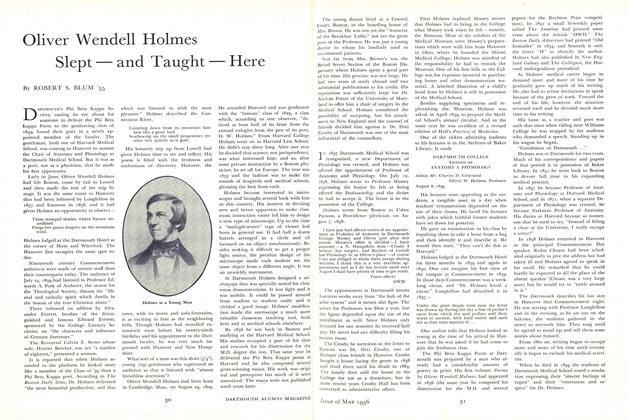

FeatureOliver Wendell Holmes Slept – and Taught – Here

May 1956 By ROBERT S. BLUM '55 -

FEATURE

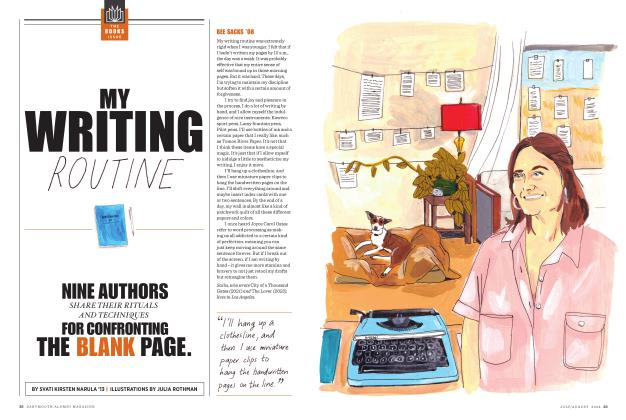

FEATUREMy Writing Routine

JULY | AUGUST 2024 By Svati Kirsten Narula ’13