Do we preach? Yes, a lot. Do we practice? Yes, a little.

IN A CERTAIN SMALL TOWN in Ohio there is street called North Professor Street. One of the professors who has an office in a building on North Professor Street is named David Orr. If his name sounds familiar, it's because Dartmouth has its own David Orr '57, a senior associate director of alumni relations. We just don't have a North Administrator Street for him to have an office on. It's plain old North Main.

Both David Orrs do good work, but it's the Ohio one I want to talk about here. Professor David one is the chair of the environmental studies program at Oberlin College. The program that he directs is different from almost every other environmental studies program in the country, including Dartmouth's. Different how? Well, it puts its money where its mouth is.

All of us environmentalists are busy saying that we in the United States cannot go on indefinitely using a quarter of the world's energy and producing a quarter of the world's pollution. We jet off to conferences to say this. We sit at our computers in Steele Hall and use laser printers to say this. (Six hundred watts whenever it's printing.) It is the Sunday after Christmas as I write, and the offices of the Environmental Studies Program have been closed since Friday afternoon. Nevertheless, the super-super high-tech copy machine, the laser printer, the fax machine, even the miserable little postage meter are all softly glowing, all wasting power. At least they were until I turned them all off just now all except the fax machine, which I don't know how to turn off Even when we're not working we're using fossil-fuel energy.

It's different at Oberlin or at least it's about to be. Under David Orr's leadership, and with money that he was mainly responsible for raising, and despite initial resistance from the administration and the trustees, Oberlin is in the processof putting up a new building for its environmental studies program. It will be strikingly different from what we have at Dartmouth—or what they have at Yale, Ohio State, etc.

Today, December 28, 1997, is bright and sunny in Hanover. That fact is perfectly irrelevant to the amount of oil-fired electricity flowing into the closed Environmental Studies office. But at Oberlin, when the new building is finished, there won't be any such flow on a sunny day. Passive solar will heat the building. The building's windows will capture and retain the warmth of the entering sunlight. Active solar will provide electricity. Solar panels will curve gracefully over almost the entire roof, all of them (on a sunny day) busily generating power. The intention is to make the new building what Oberlin calls a "net energy exporter." In other words, even if people leave their printers on sometimes, even if copy machines get worked almost to death as they do on every campus I've ever seen the building will still make more energy than it uses.

It will also eventually send water out of the building cleaner than it came in. Around here we call it wastewater, and it goes through sewer pipes to a treatment plant. But the environmental studies center at Oberlin will have its treatment plant right in the building, and it will be organic. It will be a kind of advanced greenhouse, which they are calling the Living Machine. Sometimes I'm green in the environmental sense. Right now I'm green with envy.

What seems to me the cruelest irony is this: the person who designed Oberlin's new building and who will oversee its construction is someone who knows Hanover well. He is none other than Bill McDonough '73, dean of the school of architecture at the University of Virginia and one of the half dozen leading green architects in the world. He has never designed a building at his alma mater. Reason: we have never asked him to.

We do a lot of things right at Dartmouth. Especially Bill Hochstin does he is our director of recycling, and he is a very inventive one. And especially Ross Virginia, chair of our Environmental Studies Program, does. He is a major environmental scientist. As I write he is doing research in the Antarctic. But he is also profoundly involved with local matters, such as the new Dartmouth Organic Farm and the possibility of acquiring an electric car to transport students to and from it.

There is a great deal more we could do. And if we really believe that rapid global warming is likely and that pollution is already at unsustainable levels, we damn well should. It shouldn't be all talk on Professor Street. It should be action, too.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

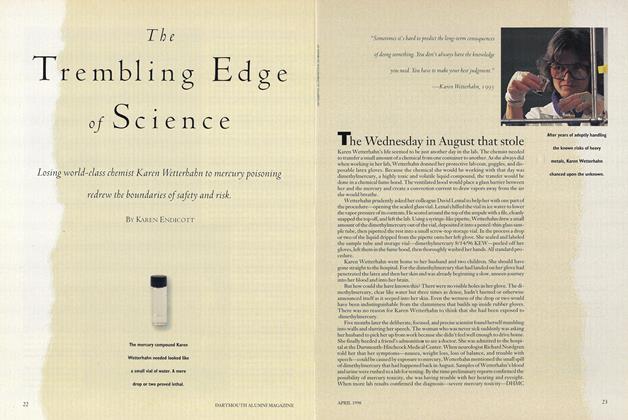

Cover StoryThe Trembling Edge Of Science

April 1998 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

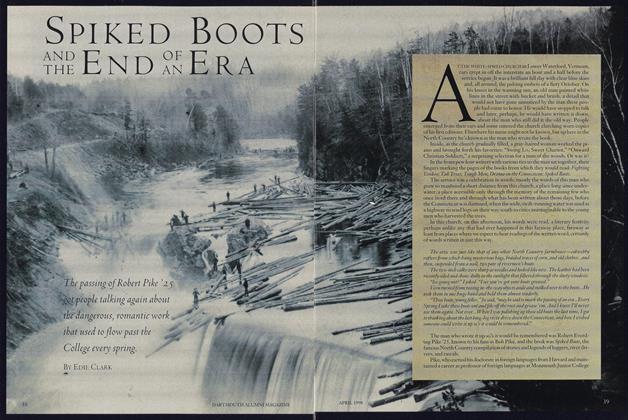

FeatureSpiked Boots and the End of an Era

April 1998 By Edie Clark -

Feature

FeatureA Change in the Weather

April 1998 -

Feature

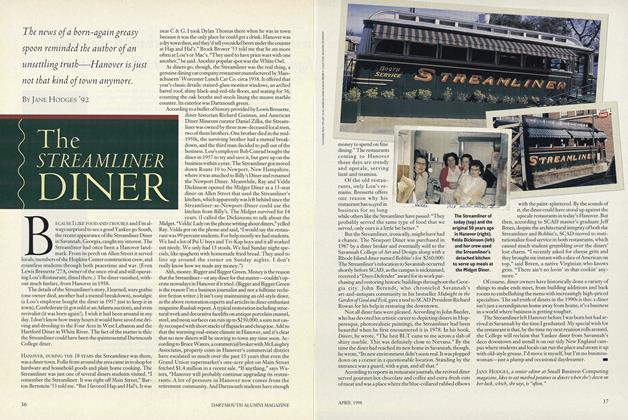

FeatureThe STREAMLINER DINER

April 1998 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Article

ArticleThe Benefits of a College Town

April 1998 By Jeanhee Kim '90 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1985

April 1998 By John MacManus

Noel Perrin

-

Feature

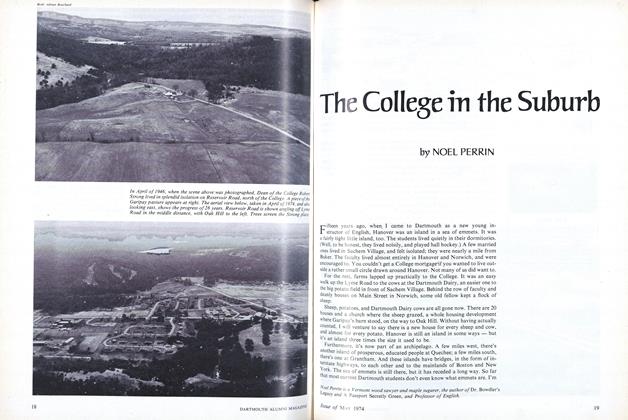

FeatureThe College in the Suburb

May 1974 By NOEL PERRIN -

Article

ArticleMinor Issues

MAY 1996 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleOffice Hours

JUNE 1996 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleThe Collis Silverware Mystery

NOVEMBER 1997 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleUntenured Gems

JANUARY 1998 By Noel Perrin -

Article

ArticleA Tale of Two Libraries

MARCH 1999 By Noel Perrin