Forget pep rallies and cheering on theold home team. In today's Ivy League,the essence of sport is participation.

IT'S 1965 AND THE DARTMOUTH-PRINCETON RIVALRY is stronger than ever. Both football teams are 8-0, and Princeton is on a 17-game winning streak. On this final Saturday in November, a sellout crowd of 45,725 watches from the stands at Princeton's Palmer Stadium as the teams battle for the Ivy Championship. The fans are wild, both at Palmer and back in Hanover, where 2,000 Dartmouth students and townspeople crowd around a closed-circuit television in the Hopkins Center, cheering from 300 miles away, oblivious to their studies or any recreational interests. After an exhilarating 28-14 Dartmouth win, the bells from Baker tower ring, not for a few minutes, not for an hour, but continuously until five o'clock the next day when the Dartmouth boys return. The night of the victory is filled with revelry and rowdiness. A bonfire is built and students feed the flames with copies of Sports Illustrated and Time; the magazines had predicted Princeton would be the better team. Jump to November 23, 1996. Dartmouth is hot once more with a perfect season and an unbeaten streak that would soon become the longest in the nation at 21-0-1. Palmer has a huge crowd again by today's standards, that is. Just over 16,000 fans turn out, and they're not even there simply to encourage the 3-6 Tigers to survive the Big Green, but to say goodbye to their beloved home of 82 years. Palmer Stadium is about to be demolished, making way for Princeton's new $45 million "multisport" facility that will have two tiers, a linear lighting system, two fancy pavilions, half-time rooms, and just two-thirds the number of seats. There's no need for any more. In fact, Princeton could probably build a stadium one-third the size of Palmer and still not have to turn anyone away. Back at Dartmouth, there is no closed-circuit television, no bonfire ready to be lit, and certainly no magazines to burn when Princeton is trounced 24-0 and Dartmouth's football team wins its seventeenth Ivy title. Facilities come with bells and whistles these days, not fans. Since 1989 the number of Dartmouth season football tickets sold to students has plunged by a remarkable 79 percent. Average student attendance at home football games has slid 45 percent. At one time, no student would even consider missing a home game. Last year home attendance averaged only 1,037 students per game, compared with 1,879 just seven years before. Dartmouth isn't alone. Throughout the entire Ivy League attendance has dropped dramatically 31 percent in the ten years between 1985 and 1995. At Yale, where a $35 million expansion of its athletic facilities is underway, serious thought has been given to mothballing the 64,000-seat Yale Bowl. Jack Merrill, Yale's capital projects director, says that the stadium will stay, but that the seats are not likely to ever fill up again, at least not for a football game.

"Much of the competition comes from television because people can see better programs fed with scholarship funds," says Merrill. "The mystique of the strong tradition of Ivy League football just can't compete with the bigger programs."

The explanation gets at part of the decrease in general attendance. Big college match-ups have become more exciting to watch. There are so many games to choose from on television that people would rather cheer from the sofa than drive and pay to watch slower-paced action. Students, however, don't seem to be watching many games at all in their dorms or in the stadium, particularly at Dartmouth. Students today simply don't have the time to watch games. How can they when most of them are competing in games of their own?

If ever there were a peak for sports at Dartmouth, it is now. Eighty percent of Dartmouth's students are involved in some form of athletics. More than 500 students visit the gym each day, and spots in aerobic classes offered each term are filled just hours after registration begins. Kresge weight room got so busy over the past few years that a new one was added and the old one improved. Even the indoor rock-climbing gym has become so congested that students are petitioning to expand it.

At Dartmouth there has always been a lot going on. At the College's beginning, students played ball and held foot-races on the Green. Townspeople believed that the grass was more suited to their grazing cows, but nothing, not even Holsteins, could stand between a Dartmouth boy and his sport. The early 1800 s football game, a more primitive version of today's, was played by just about everyone. Seniors and sophomores battled against juniors and freshmen, or the College's two all-inclusive literary societies competed: "Social Friends" vs. "United Fraters." Cricket, boxing, and fencing also kept the boys busy after classes; even gymnastics became popular when a swinging apparatus nick-named "the gallows" was erected in the Bema in 1852. As for intercollegiate competition, Dartmouth had its first experience in an 1866 baseball game versus Amherst College. The Green lost 40-10 in that inaugural match, a tragic defeat considering that Dartmouth had just won the New Hampshire championship by beating regional teams across the state. Soon other sports adopted intercollegiate schedules: crew (1873), track (1876), football (1881), tennis (1890), basKetball (1900), golf (1904), and ice hockey (1906). By 1922 teams were competing in 16 sports. Everyone did something. That's just the way it was.

But there was always room for watching games, especially football. Those few hours every Saturday afternoon in the fall inspired camaraderie as well as the chance to be a part of something big, something important. Cheering was almost a form of participation itself; it was as though everyone were on the team. Today's students, however, are so involved in their own games that they don't have the time to be Fulltime fans. There are 34 varsity sports at Dartmouth today, nearly twice as many as the national average of 17.8. Even UCLA, which Sports Illustrated recently touted as the nation's top jock school, has just 21. Among the 16 men's, 16 women's, and two coed teams, nearly a thousand varsity athletes—a quarter of the student body compete at Dartmouth. Another 500 belong to the 17 club sport teams, and countless more are involved in the College's 36 intramural sports and contests.

The NCAA reports a three-percent rise nationwide in participation in varsity sports from 1994 to 1996. Dartmouth has been about on par with that number, but the rise in Dartmouth's Intramurals and club sports has been much more significant. While compliance rales and budget constraints prevent varsity coaches from adding all promising young athletes to their teams, any student is free to join intramurals. And they do. "We had a ten percent increase in participants last year over the year before," says assistant director of physical education Steve Erickson "That's unheard of. Now 70 percent of the students participate in intramurals alone." Erickson says that the biggest interest lately has been in soccer and hockey, which follows national trends. Last year 70 intramural hockey teams battled for ice time at Dartmouth 20 more teams than the year before each with a minimum of 15 players. Intramural basketball is almost as popular, with 66 teams last year and 68 the year before.

Many of those students appear content to compete at the recreational level. "PE is my biggest competition," says Amy Appleton Dartmouth's novice women's rowing coach. "That and club sports. If freshmen can do a sport that takes up only three days a week, they'd rather do that instead of a full-schedule varsity sport." Maintaining a commitment to a team is a constant challenge for today's athletes. Even in the Ivy League, which offers no athletic scholarships and limits organized out-of-season practices, a year-round training schedule is more common than not, which has caused the near-extinction of two- and three-sport athletes. And squeezing the 20 hours per week of team practice, meetings, and games into Dartmouth's rigorous academic program requires the athletes to have "superb time management skills," as Dean Sylvia Langford puts it. Many student-athletes even help raise funding for their teams, trying to make up costs that aren't covered by the budget. "It's a real juggling act," says Langford.

Freshman Megan Beck '01 admits that her schedule is already difficult to follow. She is a member of the cross-country team, but says that she'll likely never be one of the school's top runners. She was told by her coach that she probably won't even have much chance to compete. Despite the discouragement, Beck trains five days a week with the team, and weekends on her own. Every day she runs eight miles. In addition, she aqua-jogs for half an hour in the deep end of the pool four mornings a week, and three afternoons a week after her runs, she weight-trains. She's also a freshman council dorm representative, member of the debate team, and she plans to join the track team in the spring. "I run because I enjoy running and being part of a team," she says. "Besides, when I have more to do, I get more done."

Besides time constraints, which Beck seems to have a better handle on than most, another reason for a decrease in varsity hopefuls is that the level of Dartmouth play has improved so much. "Because of the way sports have gone through a sort of metamorphosis in society, athletes have become more focused, " says athletic director Dick Jaeger '59. "They've become a lot more intent on developing their skills and their strength and conditioning in one particular sport as opposed to the old days when athletes would play two or three sports. The skill level has gone up, and it's become more time consuming for them to balance academics and athletics."

As at other schools, athletes at Dartmouth are getting stronger and faster and harder than ever to keep up with. There was a time when a decent athlete would have a decent chance of trying out and making the team. "Try-outs" are becoming a thing of the past most athletes today are identified and recruited long before the seasons begin. Walk-ons need to be nothing less than outstanding to make it onto a team—and they still better be ready to drop everything else in order to compete at those top levels.

Amber Morse '97, a fifth-year senior who is co-captain of the field hockey team, says that even during her time at Dartmouth she has noticed a large difference in the number of walk-on athletes. "I'm sure the word gets out that it's really hard to walk on to a team," she says. "Our level of play has gotten so much better. The whole Ivy League is getting better. My first year, we had walk-ons and they did well, but now there's very little chance that they would stick with a team, and even less of a chance that they would ever play."

The higher level of competition is reflected in the standings. Last year the men's tennis team brought home the Ivy title. The football team, coming off a perfect season and an Ivy championship, extended the longest unbeaten streak in the nation to 22 games before losing and finishing runner-up to Harvard. Baseball had its best season in ten years and set eight school records. In 1996 the women's cross-county team won the Heptagonals for the third straight year, finishing fifth in the nation, and followed this past fall by finishing fourth. The men's soccer team made it to the second round of the NCAA tournament after being consistently ranked among the nation's Top 20. The water polo team won a national club championship. In 1996-97 12 Dartmouth teams were nationally ranked. Six Dartmouth athletes were named first-team All-America, two were named Academic All-Americas and one, basketball forward Sea Lonergan '97, was awarded an NCAA post-graduate scholarship.

The Ivy League may not be a pipeline to the big-money, major league sports, but it has reached an overall level of competition that is stronger than ever. Football, of course, is no longer in the same league as the major Division I-A schools. But Dartmouth and the Ivies continue to excel in the more "elite" sports: crew, squash, lacrosse, cross-country, field hockey, water polo. Last year Princeton's lacrosse team won its fourth national title of the nineties, Harvard's squash teams smashed their way to the top for the second year in a row, and the Crimson's lightweight crew finished first in the nation. Total 107 All-Americas, ten Academic All-Americas, and nine NCAA scholarships.

Winter sports, as always, continue to be Dartmouth's pride. Every year the ski team places in the top ten at the NCAAs; there has never been a Winter Olympics without at least one Dartmouth competitor. And then there are the "wilderness" sports, which more and more students are turning to, even as some shy away from varsity competition. The Dartmouth Outing Club is experiencing a surge in popularity. Freshman trips are taken by 90 percent of entering students, and student membership of the club has reached 1,200, by far the largest organization on campus. The 11 branches of the DOC plan everything from afternoon bike rides to week-long canoe trips, and all their schedules have expanded. Even the most strenuous events are attracting record numbers. "Every fall, we have a 24-hour, 55-mile hike on the Appalachian Trail from Hanover to the Moosilauke Ravine Lodge," says DOC trainer Brian Kuntz. "Usually we get between 15 and 20 people. This year we had 70."

On campus there seems to be an insatiable need for expansion and renovation. In 1910 Alumni Gym was the biggest in the nation, but now teams battle constantly over practice schedules and field time. "I would say our biggest challenge right now is providing adequate facilities for the range of users we have," says Jaeger. "There's a huge crunch in our facilities."

Even as he speaks, relief is on its way, including a new artificial turf field and more indoor tennis courts that will take some of the pressure off Leverone Field House. The Carla and John Manley Varsity T raining Facility has just opened, allowing Kresge Weight Room to be used exclusively by nonvarsity athletes. A new rugby clubhouse is in the planning stages. The Skiway has expanded its snow-making capabilities and added a quad chair lift.

The next time you attend a game and notice that Memorial Field is a little on the quiet side when the sun is out and the wind is low, think twice about the empty seats. It's likely that students aren't watching because they are bike riding through the trails of Vermont, canoeing along the Connecticut, lifting weights, climbing Moosilauke. They're busy getting some of that granite into their muscles, and trying by way of participation rather than spectating to preserve a part of Dartmouth's reputation.

"Every time I walk across campus," says field hockey coach Julie Dayton, "it seems like people are ski-skating, biking, rollerblading, or running. They're on the Green walking the dog, playing Frisbee, or kicking a soccer ball." She pauses and then lowers her voice slightly. "And I know some people may not want to hear this," she says, "but I think there's a whole lot to be proud of in being termed a jock school."

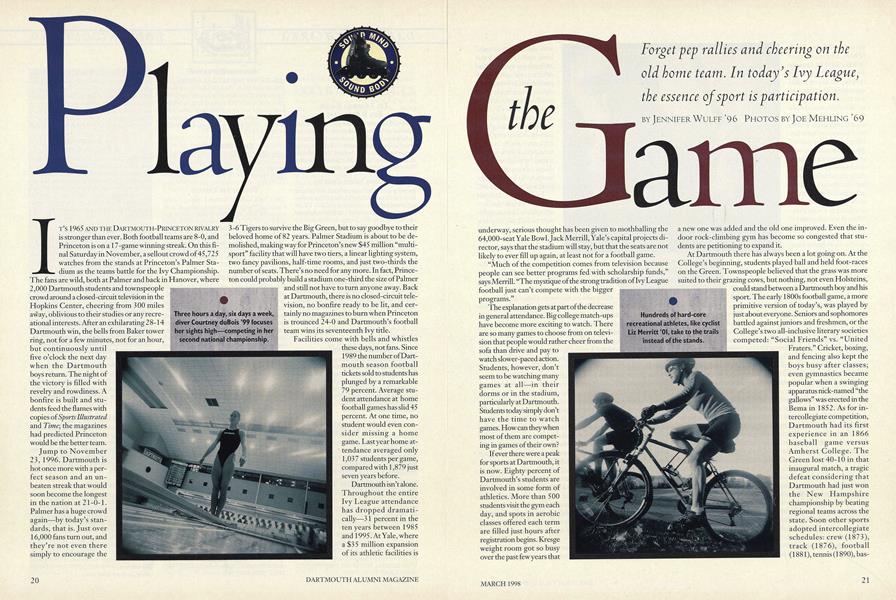

Three hours a day, six days a week, diver Courtney duBois '99 focuses her sights high competing in her second national championship.

Hundreds of hard-corerecreational athletes, like cyclistLiz Merritt '01, take to the trailsinstead of the stands.

The new breed, heavily recruited, single-sport Dartmouth athlete: shortstop Brian Nickerson '00 takes a cut during fall practice.

Ivy champion Don Conrad '99 and All-America Jenna Rogers '98 cross country for Dartmouth's long-running dynasty.

JENNIFER WULFF '96 did a short stint with Sports Illustrated before becoming a reporter at People magazine.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

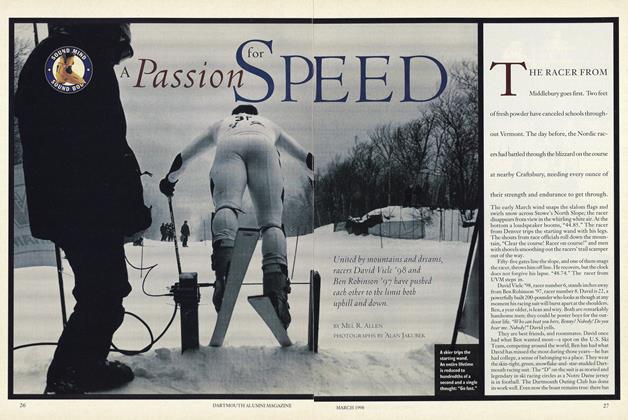

FeatureA Passion for Speed

March 1998 By Mel R. Allen -

Feature

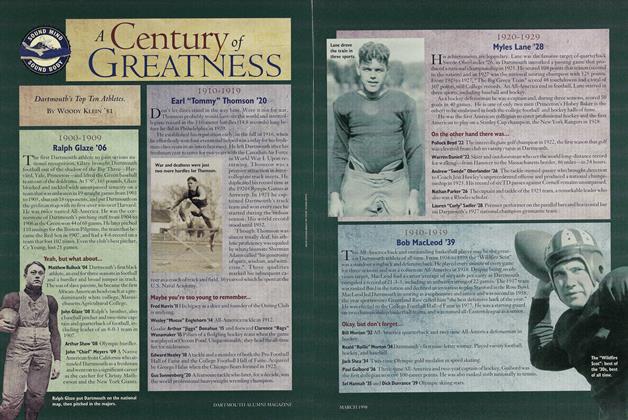

FeatureA Century of Greatness

March 1998 By Woody Klein '51 -

Feature

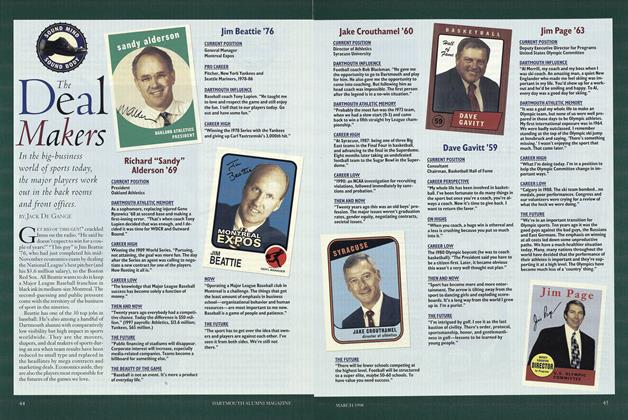

FeatureThe Deal Makers

March 1998 By JACK DE GANGE -

Feature

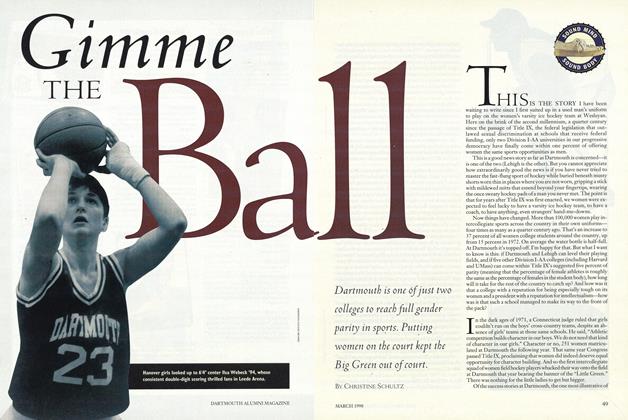

FeatureGimme the Ball

March 1998 By Christine Schultz -

Feature

FeatureOld School New School

March 1998 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureThe Good Sport in Me

March 1998 By Regina Barreca '79

Jennifer Wulff ’96

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryUncommon Knowledge From Uncommon Alumni

Nov/Dec 2004 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Article

ArticleThe Debate Continues

Nov/Dec 2004 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

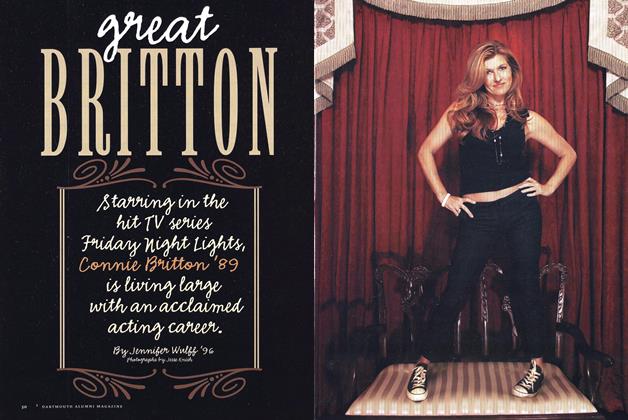

FeatureGreat Britton

Mar/Apr 2008 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Cover Story

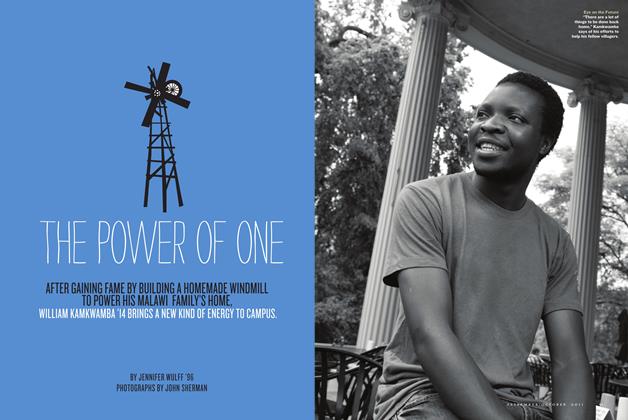

Cover StoryThe Power of One

Sept/Oct 2011 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYNew Girl in Town

May/June 2012 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

FEATURE

FEATUREUpside-Down World

JULY | AUGUST 2017 By Jennifer Wulff ’96

Features

-

Feature

FeatureALUMNI COLLEGE '65

MAY 1965 -

FEATURES

FEATURESSian Beilock

MAY | JUNE 2023 By ABIGAIL JONES '03 -

Feature

FeatureStudents and Commitment in the Deep South

JUNE 1965 By BERNARD E. SEGAL '55 -

Feature

FeatureThe End of The Story

FEBRUARY 1991 By Dan Nelson '75 -

Feature

FeatureFrom "a few curious Elephants Bones" to Picasso

SEPTEMBER 1985 By Jacquelynn Baas -

Cover Story

Cover StoryUncommon Knowledge From Uncommon Alumni

Nov/Dec 2004 By Jennifer Wulff ’96