SUCCESS IN THE WHITE WORLD has always been easy for me. My accomplishments never surprised me because they were enjoyable and relatively effortless. My grandmother, however, was usually more than surprised—perhaps even astounded."And you're an Indian!"

she would often exclaim to express the joy, happiness, and amazement she felt for me. I did well in a white school, played varsity foot- ball, basketball, and baseball, went out with wasicu (white) friends, dated wasicu women, attended an Ivy League school, and now make a living as a professional baseball player. I was doing everything she had always hoped I would do, but because I was an Indian, she did not expect me to have so much acceptance and success in the outside world of the Wasicu.

I remember when I was very young, going over to Gramma and Grandpa's house, only, two blocks from our apartment in Rapid City, South Dakota, and listening to Gramma and her mother speak Lakota to each other. During my childhood years, she never taughtme one word of Lakota; she always spoke English to me. All I knew was that they were talking "Indian" and I spoke only English.

When I came to Dartmouth as a young man, I realized that my life was not well balanced because I had never learned the Lakota language and culture, from my grandmother. Before I came to New Hampshire, a former Boston school teacher told me that many New Englanders think that "all Indians are dead." In a frightening sense, so did I. At Dartmouth, I was shocked to realize two important truths: I am an Indian and I am indeed alive.

When I first came to New Hampshire, I was at a loss because I could not answer the questions people asked about Native American life. Hell, I could not even answer my own questions! I took a Native American Studies-course my sophomore year and learned more about Indians than I had in 20 years of living as one. Yet there was something ironic and troubling about the source of my new-found knowledge: I was learning about my culture and ancestors from a white professor in a white institution. That fact disturbed me and prompted me to examine why I had ended up so ignorant. That course also reminded me of a conversation I had had with my grandmother.

While at her house during Christmas break. I asked her a question that caught her off guard, "Gramma,, how come you never taught my brother and me to speak Lakota?" She looked surprised and sat silent for a moment. Then, with a sad, heavy voice, she said, "Oh, I really wish I did. Mom and I always talked about teaching you grandkids. I really wanted to but I was afraid you would get made fun of by the Wasicu." Wasicu was one of the few Lakota words I understood. To me it simply meant "white people," but it can also be translated as "greedy ones who take the fat." Her reasoning is easy to understand when you consider her childhood. My grandmother was born April 1, 1916, in Norris, South Dakota, on the Rosebud Reservation, as Clara Virginia Quick Bear, the eldest of seven children. Her blood came from the Sicangu Oyate (Burned Thigh People) band of Lakota. When she was ten years old, it was decided that she should go to school. She had learned a little English from her mother, who had gone to school for a few years, but had no formal schooling. She had also learned the Lakota language and traditional tribal ways as well as Catholic spirituality from Old Gramma. The lessons she learned in the Catholic mission school scarred her, and eventually those she loved, forever.

Even late in her life, many of her memories of St. Francis Mission School were still vivid. She said: "It was run by all whites. They treated us very mean and I didn't like it there much. They would punish us for speaking Indian and doing Indian things. The nuns there were really mean to us and sometimes they would lock us all in one room if someone was misbehaving. There were always a few kids who were homesick and tried to run away. It would always be just a few kids but the nuns would take it out on all of us. My brother tried to run away a few times and they would always catch him and bring him back. One time they shaved all of his hair off. They did it so the rest of us wouldn't get any ideas of leaving."

I tried to ask her to tell more, but she did not want to continue. "No, they are all dead and gone and I don't want to talk about it anymore," she said. I never asked anything more about it. I was angry, but not at her. I understood that Gramma wanted us to learn the wasicu ways to keep us from experiencing her ordeal. I was angry that "civilization" had denied me the freedom to be what I was, a Lakota. I look in the mirror and there it is, my Indianness. Yet I did everything in such a "white" manner that my white friends and others would distinguish me as the "good Indian" and say, "You're not like them." This acceptance is exactly what my Gramma wanted for me. According to her, being an Indian in a white world gets you "made fun of."

The first racial insult I can remember being directed at me happened soon after the training wheels were removed from my bike. A maintenance man, coming down the stairs of our apartment building, did not see me approaching on my bicycle. I had to swerve to avoid hitting him. I stopped to see if he was all right and to apologize, but before I could say anything he blurted out, "You fucking Indian!" That insult scared me. I must have heard many similar comments afterward, because my mother said I came to her several times and told her that I wished I were white. She would lovingly respond, "Tell them you are proud to be an Indian."

Tell them that I was proud? Proud of what? I knew nothing to be proud of. I was on welfare and received free lunches. I was a "savage" who killed white American settlers. I was a boogey man, a gut eater, a dog eater. I was an exile in my own land. I wasn't aware of why my akicita (warrior) relatives fought and died for their ways and for the land. I did not know how my people lived, and I had no pride in my Sicangu Lakota. I didn't know the power and strength of the old stories. I didn't know how the name-calling wasicu had stolen my homeland and killed my ancestors. Ignorance was at the root of their misdirected bigotry, as well as my own sense of inferiority.

Thus, during my upbringing I made myself acceptable to nearly every white person by being just like them, wasicu. It was not an entirely deliberate effort on my part to fit in. These people were my friends and we had much in common and shared a similar sense of humor. I did what made me happy and really had no idea what my Indian identity was.

During high school, I was usually the only Indian in any group I was in: football, basketball, baseball, and all my social groups. I felt overly cautious when my white friends were "causing trouble." Because I was the only Indian, I was often singled out as the troublemaker. In sports, I had to be better than the non-Native players, and in social situations, I had to be more humble than others to avoid problems.

High school never presented any major problems for me. Everything—classes, friends, teachers, sports, and dealing with other Indians—was easy. I was just like any other kid who was curious about drinking and crossing over the lines of authority. I often went to parties—Indian, non-Indian, or a mixture of bothand did my share of drinking and other stupid juvenile acts. I often drank until I got sick, but that behavior is fairly normal among high school kids. I was involved in smashing a mailbox with a baseball bat, overturning a hotel ice machine, and other small-time crimes.

All of these juvenile acts were gradually coming to a head when my baseball coach, Dave Ploof, confronted me. "Bobby, you have a lot of things going for you. I would hate to see your friends and other associates screw it up for you." This was the best advice anyone could have given me.

I was an investment for Coach Ploof. During the next three years, I pitched on his American Legion team. I owe much of my success to him because he taught me the discipline I needed to become a mature ball player and to always play hard. He touted my baseball skills and maturity to the college baseball scouts.

I also played basketball. My senior year on the team remains one of the best times of my life. We finished with a great record and made it to the state tournament. I was the only Native American on the team and was very vocal on the court; I was perhaps our team's biggest cheerleader. But I was also friendly towards the opponents, which surprised many of them as well as the fans; I was supposed to be a mean, vicious, and dirty basketball player because of my Indian blood. People sitting in the stands gave "war whoops" and yelled insulting names at me during games, but I still played my heart out and enjoyed it.

Both on and off the sports field, I was the "good Indian" to nearly everyone in my school. Being elected the Homecoming King in my senior year shows how well I fit into that image at Central High. Indians normally frightened the people of Rapid City, adults and teenagers alike.

For my high school graduation, I was chosen as one of the commencement speakers by the faculty. It must have been a good speech because it made several students cry and the audience seemed to listen intently. I wondered, was their interest in my words, or were they merely surprised to see an Indian up there? Whatever their opinion was, speaking for my fellow seniors was an honor and a privilege that I had earned.

The day before the graduation ceremony, another honor —a spotted eagle tail feather—was presented to me by Sidney and Shirley Keith, a traditional Lakota couple who live in Rapid City. Sidney is a Lakota spiritual leader. He and his wife performed an eagle feather ceremony for all of the Lakota high school graduates. They sang to the four directions and to the sky, the earth, and finally to us. I wish I could describe how they sang because it was so powerful. Sidney and Shirley's voices calling to the spirits through the wind was something that I had not heard in years. We all watched and listened silently.

In Sidney's aged hands were many spotted eagle tail feathers, all about a foot long with dark brown plumes that had a milky white area at the bottom near the quills. At the base of each of the quills was a leather loop attached by a twisted red porcupine quill. I knew these feathers were holy. He stopped singing for a moment and lit some sweetgrass. He "smudged" the feathers by circling them with the smoldering braid of grass in order to make them sacred and give them power before presenting them to us. He then began again with the same powerful, rhythmic singing. Though I had no idea what the words meant, I stood with my mother and listened out of deep respect. Or was it fear?

I am Lakota. Why should I have listened in fear to a Lakota eagle feather ceremony? Because I had no clue what was happening. I recognized the sweetgrass because I had seen my grandmother use it many times before when I was a boy. Seeing and smelling the burning sweetgrass in Sidney's hands brought back memories from my youth.

"Why are you doing that, Gramma?" I remember asking when I saw her light a thick braid of sweetgrass during a powerful thunderstorm.

"I don't want the house to get struck by lightning. This grass will help protect the house and us," she said as she walked from room to room waving the smoking braid of sweetgrass from side to side. She would mumble a prayer in Lakota at the same time. She often prayed in both sides of her life, the Lakota and wasicu, sides.

When Sidney and Shirley's song came to an end, they turned to us and he told the story of the eagle feather.

In the old days they gave thesefeathers to people who did a good deed.That deed could have been anything—saving a life, doing well on the hunt,doing brave things when it came timeto fight, or becoming an adult. Timeshave changed, but the honor in accomplishing tasks has not. You kidshave done a great thing in graduating from high school and that is whatthis feather honors. Use it in the newworld you are entering for strengthand guidance.

They gave each of us a feather and shook our hands. I then had something that visibly made me more Indian than I had ever been before. The feather connected me with a part of myself that I had never known about, and I was uncomfortable with it because of my lack of understanding. That day also opened my eyes and curiosity to the spiritual worldor, in American terms, the religion—of the Lakota. Next to my Lakota blood, that feather became the most significant Indian object I possess. It changed my perspective and attitude toward everything around me. My brother recently said to me, "When you got that feather, that's when you became an Indian. You never hung out with Indians before you got that feather." That blunt truth hit me hard. But the true significance of the feather dawned slowly on me as, indifferent to my Native .American identity, I searched for my true self away from my people.

Finding friends at college was fairlyeasy because my ability to throw a baseball made the transition from South Dakota to Dartmouth much easier. According to the College's baseball coach and The Dartmouth, I was the number one baseball recruit that year. That reputation made it very easy for me to meet people. The baseball team had guys in many fraternities who knew the ins and outs of Dartmouth College. "Yeah, this guy is cool. He's a good ball player," I frequently heard. Word quickly got around among the freshmen, and I soon had friends.

Without my baseball skills, I probably would not have met the people that I did. Most of the first people I met were wasicu, and my identity as a Native American was never more than a passing issue to most of them. That I came from South Dakota was more of a revelation to people than my Indian heritage. Most of them had never met any Native Americans before, so they had some basic misconceptions about me. They assumed I could run silently through the forest and shoot a bow well. They did not know enough to be intentionally racist, only ignorant.

But these harmless assumptions and jokes had another side to them that was in- suiting, racist, and fall of stupidity. Many conservative people at Dartmouth have felt that my presence, or any other Native American's presence on the campus, is simply a big favor they are doing usthat we do not really belong here. Instead, we should stay on our reservations, out of the way of progress and intellectual enlightenment. To many students, and to the College in general, we are only as real as the old Dartmouth Indian symbol that many people claim is a tribute to all Native Americans. People see a symbol or a costume, but often fail to see the human being under the braids, buckskin, and paint. They do not know us or how we perceive the world; people only assume that we are out of our element and need special guidance. I think no white person can ever truly understand the thoughts and feelings of a Native American; we can only ask wasicu to respect the Native perspective. This was evident early during my freshman fall at Dartmouth.

The coach who recruited me for baseball had informed me of Dartmouth and its fabled beginning as an institution to educate Native Americans. When I arrived at Dartmouth, he and I immediately became friendly, and we often talked openly in his office. Though he listened attentively as I talked about life in South Dakota and my Lakota background, he already had some preconceptions about me and Native Americans in general. Behind my back, he asked one of my teammates to watch out for me. "Don't let Bennett hang out in the fraternity basements, because his people have a big problem with alcoholism. I want you to watch out for him," he said. I was very angry when my teammates revealed this conversation to me after that coach had left the College. I acknowledge the problems with alcohol that many—but not all—lndian people face, but I did not appreciate being stereotyped.

Other incidents at Dartmouth forced me to confront my Indian identity. My freshman roommate was interested in my Native background because he was taking an environmental studies course in which he read the journal of Lewis and Clark. Lewis and Clark passed through the territory of my ancestors, and my roommate asked me to verify one observation in the journal.

"Hey, Bob, have you ever eaten dog?" he asked. "These guys said the Sioux fed them dog meat."

I replied confidently, "No they didn't. I haven't eaten dog and they didn't eat it either. They were buffalo hunters and wouldn't eat dogs. They used them to pull the travois and carry packs. They weren't food."

My roommate insisted that we did and even showed me the passage in the journal. How could I refute what was right in front of me in black and white? I was confused and also embarrassed because he now doubted my Indianness. I also doubted my Indianness. That early lesson at Dartmouth about my own cultural ignorance pushed me to know more about my ancestors.

I met some other good friends through the Native American Program (NAP), although my initial involvement in the program and in the student group Native Americans at Dartmouth (NAD) was quite limited. NAD's activities didn't interest me a great deal. I just wanted to meet some other Native Americans in this strange place. I never thought too much about the political aspects associated with NAD because I had my own agenda. I was a baseball player, and that occupied most of my time and effort each term. Then I rushed a fraternity. The combination of the two shaped who my friends were and, despite my limited interaction with NAD, I came to know many of its members as well.

Academics took up much of my time during my first three years at Dartmouth. One class really opened up new doors for me. The class, titled Native American Studies 22, "The Invasion of America," made me fully aware of something that I had been lacking all of my life—a Native American perspective on my own Lakota heritage. None of my previous classes had really touched my inner self.

The teacher, Professor Colin Calloway, had studied the Abenaki in Vermont and had learned much about the Crow people and their reservation while teaching at the University of Wyoming. I listened very attentively as he spoke of his experience with the Sioux people. "I have spent a lot of time among them and can recognize the sound of their language, but by no means can I speak it," he said. "I only learned this." He said a Lakota phrase that means "bullshit" in English. I laughed aloud soon after he finished because I recognized one word of the phrase, cesli, which means "shit. "My chuckle was heard by the entire class and every pair of eyes was suddenly on me. Professor Calloway said, "I see we have a Lakota in here with us. Did that sound right?" I replied yes, and he continued with his material.

I had made myself the "real Indian" of the class by recognizing one word of the Lakota language. But the extent of my Indian abilities was quite limited. I became frightened of my ignorance once again. I became aware of how white I was during each of his lectures on some other tribe, and I was overwhelmed when he came to the Lakota section of the class. I did not know the Lakota were the TitonWan, "dwellers on the prairie," and the western people who spoke the Lakota dialect of the Siouan language. I did not know there were seven bands of Lakota or two other groups of people who were also Sioux. I did not know anything, yet Professor Calloway always looked to me for approval when he pronounced the names of one of the bands of Sioux, and I usually gave him a nod. Other people would look to me when he said something. If only they had known that I didn't know much more than they did.

In the grand scheme of Lakota knowledge, I knew nothing. After a year and a half at Dartmouth, I began to question my life as an Indian, which was really my life as a white guy who looked like an Indian. I was trying to be the person my well-meaning mother and Gramma wanted me to be: an Indian Catholic who only knew the ways of the wasicu.

Professor Calloway's class dealt with the issue of Native religion versus Christianity. Religion was used as a tool of destruction against all tribes in the colonization of North America, and I found it difficult to accept that I was part of an institution that had destroyed so many people's cultures and lives. I did not want to be a part of that institution anymore. I wanted to learn how to be a Lakota, not a white crusader or a Catholic with an entirely different culture, spirituality, language, and history.

I made the strongest attempt to regain what had been denied to me by enrolling in a Lakota language class. The professor, Elaine Jahner, had written a Lakota language book with a Lakota woman earlier in her career. She was raised in North Dakota and had a good understanding of and respect for Indian culture and thinking. She knew the sound of the language and many words and pushed us patiently.

Four students, three Sioux and one Ojibwe, met weekly with her in her office. I wanted to learn Lakota very badly because I believed the language would return some of my identity. Though I learned quite a lot, Lakota was a difficult language to pick up for a 20-year-old whose only familiarity was with Latinate languages.

When I told Gramma of the Lakota class and Professor Jahner, I felt proud yet nervous. I think she may have been a bit apprehensive about my reasons for learning. "Oh, you want to be Indian so much, don'tyou, Bobby? But..." she said. There was usually a "but" in everything she said regarding my search for identity. She did not want me to get distracted from learning the wasicu ways and playing their game of baseball.

Despite her warnings and hesitation, she opened up to me before I left for my junior year at Dartmouth, after doctors found that she had developed lung cancer. "Don't worry. I'm going to beat this," she told me before I returned to college. "I've been to ceremonies before and they helped me then. They'll help me now. Just go to school and don't worry about me. Just pray for me." I never knew she had gone to traditional healing ceremonies. She was even more traditional than I thought.

I returned to school for my junior year and often thought of her. I called her to ask questions for the Lakota class, and she spoke more freely than she ever had in answering my questions despite her intermittent warnings. She started her chemotherapy treatments later that fall.

I knew the side effects of chemotherapy —weight and hair loss—so I was nervous and frightened when I came home for Christmas break to see my grandmother. However, she had changed very little. She wore a little turban and had lost weight, but her voice and eyes still had their familiar strength. We talked a lot about her childhood and how she met Grandpa. She truly opened up to me for the first time, and I think it was because she realized her time was limited. I talked to her several times about my Lakota class. She taught me how to pronounce the word "deer" in Lakota. I wish I could remember all of the Lakota conversations we had, because they were the first ever. I hated to leave her at the end of Christmas break because I knew I would not be home until the end of the following summer. It was a long nine months without seeing her. When the time came to see her again in September, I knew the little time I had was going to pass quickly and then I would never see her again. That one week, those seven short days, we spoke of our lives together and said our final farewell.

The chemotherapy and radiation treatment had failed to destroy the tumors in her lungs. She realized her time had come and she just wanted to go home and stop the grueling cancer treatments. During that week in September, we had several great conversations about our lives. I was always on the verge of breaking down, and every time I did she would tell me to stop. One night, she made herself sit up, put her arm around me, and consoled me, the healthy grandson, with an amazing strength in her voice. "I'm not afraid, it's my time to go. Bobby, you be strong for everyone here and just use the blessings you got from God. Don't cry for me because I will be fine." She had such strength in her final months.

During one of our conversations, I asked my grandmother how the Lakotas described "life" with their words. She thought for a moment and casually said the words in Lakota. Of course I could not understand them, sol asked her what the words meant in English. She thought for another moment and said, "I have come this far." "I have come this far" is a literal English translation of the Lakota concept of "life." The old Lakota had a very insightful perspective on the world, and these were the most profound words I had ever heard from her.

"I have come this far." That phrase hit me that night. Ironically, my Gramma spoke the words at the end of her Lakota life. When she left this existence, my life—"how far I had come"—was just beginning. I was shedding my wasicu version of life and beginning to understand why my forebears preferred to die in battle to protect their ways rather than become puppets of the wasicu world. Now I wish my upbringing had been as Indian as possible. I grew up solely as a wasicu, and that angers me greatly. My "I have come this far" is far from over and when it does end, I want to be as content and unafraid as my grandmother was. Though she suppressed much of her Indian identity to protect herself, her children, and her grandchildren during her life, she left this world content, ready, and unafraid as a Lakota.

At her funeral, I put a baseball next to her body, just as I had for my grandfather years before, so she could hold it for me on the other side. Thatway I can play for her and Grandpa and they can give me their strength. I feel her spirit every day and I have seen her in several dreams. In her life I found strength, and her death only enhances the power we find in each other. When they closed the casket and the shadow covered her face forever, I truly realized why she did not teach me. I have to teach myself and also those who do not understand.

I am angry that a place like Dartmouth was necessary for me to figure out my identity and direction in life. The college has educated me in the wasicu sense, which contradicts much of the Indian knowledge I have acquired recently. Dartmouth has only licensed me as an educated Indian in the world of the wasicu, but that learning will be valuable in helping me help other Indians and myself. I have found more of myself, more of my spirit, and in that discovery comes knowledge. Knowledge will come to me and it will be in control. I just need to keep that in mind, relax, and allow everything that eluded me as a boy to come to me as a man.

Wanbli Wanji emaciyapi na han mawicasa Lakota yelo.

I am One Eagle and I am a Lakota man.

My journey is far from over, and one of my yet-to-be-attained dreams is to stand on a major league pitcher's mound with my hair in a braid, knowing that I have accomplished everything I ever wanted. Standing there alone, standing as WanbliWanji, will be a testimony to the struggle of Native people and the individual batde waged within all of us. Stand proud, Indian people. Mitakuye oyasin.

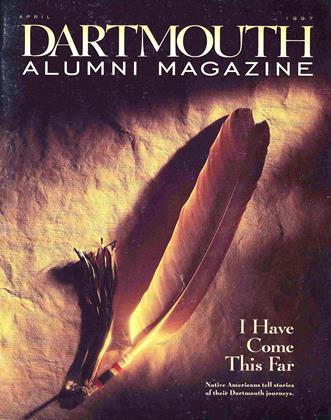

"The positive ripple effect of one Dartmouth Native explaining to other students what it is to be human is incalculable," writes Louise Erdrich '76 in the foreword to First Person, FirstPeoples: Hative American College Graduates Tell Their Stories. Compiled and edited by Dartmouth education professor Andrew Garrod and former director of Dartmouth's Native American Program Colleen Larimore '85, the book is due out from Cornel! University Press this spring. The stories that follow are excerpted from the book. -The Editors

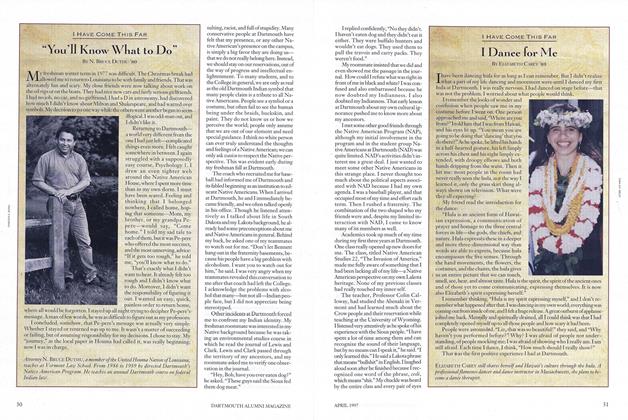

BallHurler Bennett's strong pitehing arm made campus friendships come readily, if not always easily.

ROBERT BENNETT, a jnember of the Rose-bud Sioux (Sicangu Lakota) Tribe, is a pitcherfor the Huntsville (Alabama) Stars, a ClassAA affiliate of the Oakland Athletics. A GrassDancer, he plans to help Native people as alawyer, counselor, or educator after his baseball career. He completed this essay shortlyafter graduation.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureNative America at Dartmouth

April 1997 By Karen Endicott -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWhy Don't You Say Anything?"

April 1997 By Davina Begaye Two Bears '90 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMy Grub Box

April 1997 By Vivian Johnson '86 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryI Dance for Me

April 1997 By Elizabeth Carey '93 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWe Are Not Your Indians

April 1997 By Arvo Mikkanen '83 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"You'll Know What to Do"

April 1997 By Bruce Duthu '80