United by mountains and dreamsracers David Viele '98 andBen Robinson '97 have pushedeach other to the limit bothuphill and down.

THE RACER FROM Middlebury goes first. Two feet of fresh powder have canceled schools throughout Vermont. The day before, the Nordic racers had battled through the blizzard on the course at nearby Crasftsbury needing every ounce of their strength and endurance to get through.

The early March wind snaps the slalom flags and swirls snow across Stowe's North Slope; the racer disappears from view in the whirling white air. At the bottom a loudspeaker booms, "44.85." The racer from Denver trips the starting wand with his legs. The shouts from race officials roll down the mountain, "Clear the course! Racer on course!" and men with shovels smoothing out the racers' trail scamper out of the way.

Fifty-five gates line the slope, and one of them snags the racer, throws him offline. He recovers, but the clock does not forgive his lapse. "48.74." The racer from UVM steps in.

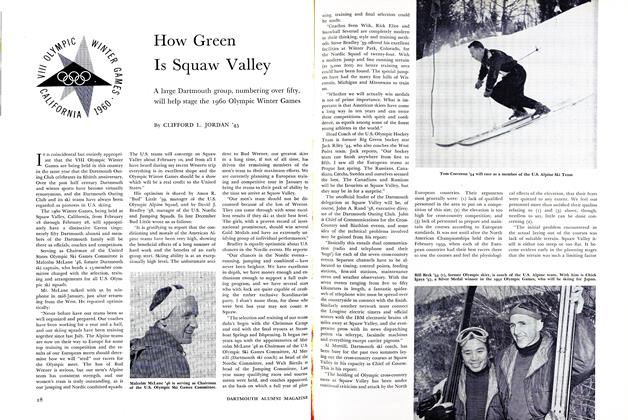

David Viele '98, racer number 6, stands inches away from Ben Robinson '97, racer number 8. David is 22, a powerfully built 200-pounder who looks as though at any moment his racing suit will burst apart at the shoulders. Ben, a year older, is lean and wiry. Both are remarkably handsome men; they could be poster boys for the outdoor life. "Who can beat you here, Benny? Nobody! Do youhear me. Nobody!" David yells.

They are best friends, and roommates. David once had what Ben wanted most a spot on the U.S. Ski Team, competing around the world; Ben has had what David has missed the most during those years he has had college, a sense of belonging to a place. They wear the skin-tight, green, snowflake-and-star-studded Dartmouth racing suit. The "D" on the suit is as storied and legendary in ski racing circles as a Notre Dame jersey is in football. The Dartmouth Outing Club has done its work well. Even now the boast remains true: there has never been a Winter Olympics without a Dartmouth athlete. David and Ben were drawn here by the legends, "a sense of mysticism I didn't feel anywhere else," as Ben put it, but history and tradition give neither speed, nor points. What they do give is a desire to hold up your end. From eight varsity men alpine racers, Coach Peter Dodge '78 has picked them, along with sophomore Andrew Pennock '99, to represent Dartmouth at the 1997 NCAA Championships.

"This race is yours, Dave. It's yours!" Ben shouts back. Yelling is not his natural style. From boyhood he preferred silences. "He always just thought a lot," said his father. David has shaken him out of that.

They have slipped the course twice, memorizing the twists and turns in the terrain, looking for what they call a course's "rhythm," where to ski fast, where to ski conservatively. They hope they have an edge: the course was set by Peter Dodge. He has set a demamnding course, but one without tricks or traps, a course to reward the most technically proficient skiers. The course should favor David's strengths.

Ben, well, all year Ben has been what Dodge called "a wild card." Capable of special runs when he could beat anyone, anywhere, but prone to wild runs, a Hairsbreadth from disaster, needing acrobatic recoveries to finish standing, and, too often for Dodge, not finishing at all. Though he had made the NCAA team two years in a row, Ben had needed a strong showing at the season-ending Middlebury Carnival to earn his way back. He got it, finishing third in the giant slalom and fourth in the slalom, one of his best races of the year.

They've been at the top for 15 minutes, talking swinging their legs around, trying to stay warm in the frigid air. They have gone off alone for a few minutes, racing through the gates in their minds, a time when they ski faster than light. A time when they always win. Now, they need to stop thinking. So they shout and scream and pummel each other on the shoulders. "Yours,Benny. This is your race. You gotta do it!"

LONG BEFORE THEY WERE BORN, Dartmouth helped make them ski racers. David's father, Jim Viele, was the son of a Vermont one-room schoolhouse teacher. He raced at Worcester Tech and after college made fast friends with a business colleague named Ned Gillette '67, a former Dartmouth Nordic Olympian. Both men were on the cusp of executive business careers when they decided to head west together. Ned got a job at a brand new skiarea called Copper Mountain; Jim Viele found work as a ski instructor at Vail.

Ben's father, Win Robinson '60, a Massachusetts native, met a fraternity brother in 1971 at a Dartmouth football game who prevailed upon Win to join his family timber business in Maine.

So David grew up in Colorado, Ben in Maine, but because great mountains, Vail and Sugarloaf, loomed over their homes, they shared the same dream: to be Winter Olympians. These mountains, their dreams, have made their lives almost mirror images of each other.

At 18 months of age David was on 70-cm skis, screaming in delight. By four he was skiing deep powder in Vail's back bowls, while in Maine adults stopped and stared in astonishment as Ben sped effortlessly down Sugarloaf s imposing steeps. At age eight David won the Buddy Werner Colorado State Championship, beating all 8-,9-, and 10-year-old racers. At age 9 he entered 15 races, and won 14. The same year David raced in the Rocky Mountain Junior Olympics, Ben competed at age 11 in the New England Junior Olympics, at least two years ahead of his peers. As teenagers they both gave up "normal" high school life to devote themselves to ski racing. David came east to Burke Mountain Academy in Vermont, and Ben attended Carrabasset Valley Academy, in the shadow of Sugarloaf. Ski racing at this level is excruciatingly expensive, but while money buys access to training, it cannot buy courage, nor resiliency, and as young men both David and Ben have lain on snow-covered mountains with the inside of their knees torn apart.

Only a year earlier David, then racing with the U.S. Ski C Team, had been at the top of a giant slalom course in Oregon. "I didn't want to go," David said. "It was too foggy and I knew it wasn't safe. I went third. The first two racers did not finish. I came over a knoll by a sweeping turn, out of the fog, then back in the fog. I hooked a gate that I didn't see. I heard a sharp pop. I knew the knee was totaled. All of the summer of '96 I did rehab. In October I went to Switzerland for training camp. My knee was killing me. In November, in Colorado, I went through soft snow, caught an edge. I went up in the air, and I came down on one leg. The tendon tore a big piece of bone off the knee cap. I was already on painkillers for the other knee. I figured I'd had enough. I came back to Dartmouth after Christmas."

He came back a hurt, disillusioned, burned-out ski racer, who from age 18 had attended Dartmouth only sporadically in between the international racing season and for too long had felt that his worth went only as far as his racing points. But by January his injuries had recovered enough for him to start over, this time under the eye of Peter Dodge. David found he still loved the sport.

"I thank God my parents said, 'You have to go back to Dartmouth," he said. "I saw the level of skiing wasn't different from the U.S. team. These past few months showed me how much racing meant to me."

Peter Dodge understood David because he had been there. He too had been a racer whose years on the U.S. team took him off campus every winter. "I struggled on the ski team," he said. "Life on the U.S. Ski Team can be especially tough if you're independent." Dodge never graduated. He left the U.S. team, turned pro, and prospered. He studied skiers, saw what worked and what did not. He worked with young skiers at ski camps, and found his calling. When he returned to Dartmouth nine years ago as men's head alpine coach, Dodge "reconnected with something, a sense of finishing."

His task with David was to get him to remember the pure joy of performance. "David now wants to do well for himself," Dodge said before the race. "Where that gets him in the ski world isn't as important as simply going for speed and the perfect race, a race where he turns exactly where he wants to." It's what David calls touch. "Touch is not putting too much pressure on a ski, but barely holding onto an edge, cutting a clean arc, like skating."

Dodge believes the athletic body can be pushed harder than it thinks it wants to be, that it will respond to the right pressure. David Viele had no idea what was ahead of him when he arrived for his first Peter Dodge training session. "He put me through a workout so hard I threw up," said David. "Nobody had been able to do that to me before." In October all the ski racers, men and women, alpine and Nordic, varsity and development, had run up Moosilauke's Gorge Brook Trail, 3.6 miles, 2,000 vertical feet, nearly an hour's worth of pain. They were running not just against time and a mountain, but history: their route was the site of the first European-styled downhill race in America. Dodge took his downhill racers to Memorial Field for wind sprints up the bleachers. When he knew they were exhausted, he gave them one more sprint. This time they had to carry a partner. Dodge produced a box, 18 inches high. He had a stopwatch. He wanted to see who could jump on and off the box the most times in 90 seconds. (120 was the record.) When the skiers finished, they could not walk.

"The strongest skiers are the fastest," Dodge said. "And at the end of the race, when you're so tired, it's strength that protects you from injury."

"If you know you're strong," Ben said, "you feel that nothing can stop you. You feel invincible." Dodge has never had a varsity skier quit on him.

Every day, at the Skiway David and Ben have pushed and prodded each other go faster, ski cleaner. They like to end their days from the top of whatever mountain they are on by seeing who gets down first.

THERE ARE 25,000 ALPINE RACERS registered with the U.S. Ski Association. Only 33 stand here now at Stowe, on a March morning on North Slope, with a chance to be NCAA alpine champions. On the giant slalom run two days earlier, David had been in first place after the first run. He ended up finishing fourth in the GS, and Ben seventh. Their scores had put the team in a position to redeem a disappointing season that saw the Dartmouth men, having lost John Kline '99 and All-American Jean-Pierre Daigneault '97 to injuries, looking up to UVM in the carnival standings most of the time.

The racer from Washington steps into the start. David kicks into his bindings. His skis, as pampered as infants, are blood sharp and waxed by Peter Dodge. Now, the racer from Alaska. Twenty seconds for David to wait. In the start gate he places his poles in the snow. Ten seconds. He breathes deeply, holds it a moment, then lets it out. "Three. Two. One." His arms and shoulders are in motion before he kicks open the starting wand. He holds no thoughts except this: "Get down fast as I can."

The racer from Williams steps in. Ben Robinson breathes deeply, lets it out. He kicks into his bindings.

THE YEARS HAVE GIVEN WIN ROBINSON a sense for where the crucial parts of a race course lie, where danger waits. "I try and stand where I know the race will probably be won or lost," he said. Long before his son, Ben, races, Win climbs the mountain on Snowshoes He is scouting the course. Son of Winfield Robinson '26, Win is a lean, athletic, and handsome man, blue eyes, white hair, a timber executive who has long lost count of mountains he has climbed this way. It is how he gets through race days. "It really doesn't get any easier over the years," he said. "I can't just stand with a large group and watch the race."

I stand beside Win and his wife, Vici, admissions director at Carrabasset Valley Academy. We are perhaps 200 feet from the start, where the gates hug close to the edge. We stand in the new deep snow. The cold starts in the feet and works upward, not letting go. I have two boys who ski race. They are but 11 and 8 and a world away from the pressure of an NCAA championship and speeds that tear bone away from flesh, yet there is so much that seems the same, as I stand here beside the Robinsons: the sharp scrape of the skis' steel edges biting into the course, the sudden silence when David Viele races past, his breath, uumph, uumph, audible against the sound of his pole guards banging the gates. He is having a confident, strong run, maybe a top-three run. When he passes us I feel the desire to look away, as if looking too long, too hard, will make him fall (I am one of those who sometimes looks away when my child comes through) and then, right there, the sharp gasp from Vici, the groan from Win. David has leaned in too hard, he has fallen. We urge get up, get up, as he climbs back, his poles stabbing at the snow, climbs back through the gate, fighting through the disappointment, having to find his speed again from a dead stop. He races to finish, hopelessly behind. "64.39." "What happened?" says Win. "He was having a great run. He was right on it."

And then again, the urge to look away because now it is Ben on course. He is among the elite collegiate racers in the country. If Ben Robinson played basketball or football at this level his career would be just beginning, but his dream of making the U.S. team has burned down. He is 23, smarter and stronger than when he arrived on campus, but the U.S. team has little interest. He is considered too old to develop. The Robinsons know they are watching the end of his career.

"I remember the day he started," Win had told me the day before. "We were at Sugarloaf and we just took a run and he came with us. And I noticed all the parents staring. An instructor came over to us and said, 'Give him to me for the rest of the day.' And she took him, the whole day. By the end of that day he was off on the mountain, on his own. He was four years old. They told me, 'You can't teach what he has.'"

When Ben was eight and his brother David '95 (who later skied on the Dartmouth development team) was ten, they raced throughout Maine. Friday nights, Vici packed a basket full of sandwiches. Win tuned skis with the boys in the shed. When the boys got old enough they worked on the skis alone, coming into the house smelling of hot wax and their hands fall of tiny steel slivers from the sharpened edges. They'd rise by 4:30 a.m. and drive to Lost Valley, Pleasant Mountain, Sunday River. Win and Vici have driven five hours to a race, only to see their sons wipe out after three gates. But mostly, Ben won races. "We had no idea where all this was leading," remembers Vici. "We just did it." Ben's talent took them into regional, national, and then European meets. One year, even before the ski academy, they found they had spent well over $12,000. Along the way they saw so many of Ben's peers burn out, leave the sport behind. Often the parents burn out long before the kids.

I told them I felt it already, only four years into it: the latenight ski tuning, packing the car in the dark and cold, driving over twisting mountain roads and arriving at lodges before the coffee is even hot. All this for two runs, perhaps 90 seconds of racing. No, they said. They never thought it wasn't worth it. Ben's passion for speed made it worth it. Ben used to get to Sugarloaf at 7:30, before the lifts opened, and the attendants would let him ride up so he could have a deserted mountain to race down, all to himself. His dream was contagious.

Ben Robinson has made perhaps 100,000 runs in his life. Now, on one of his last as a competitor, he speeds past us, fast, strong, his hands forward, his mouth taut with concentration. Nobody speaks. Then, four or five gates below Win and Vici, where David had fallen, Ben slips out, just a hair, just enough. Win doubles over as if he'd been struck in the belly. He never would have said so, but in his heart he wants a win for Ben as much as he'd ever wanted one; it would be Ben's gold medal. Win and Vici strain to hear the time. "45.87." It is not bad, good enough for ninth. Good enough for "what if..." Without the split-second skid, what then?

We watch some more racers, then walk down. Ski racing is one of the most sociable of competitive sports these racers have known each other for years, from ski academies, from racing in Europe and South America, from summer training camps out west. Racers learn early to get over a disappointing run; the ones who cannot do not last long. When we reach the lodge Ben and David are relaxing with friends. The lodge is noisy with laughter. The second run will soon start. Then the women will follow.

TEAMMATE ANDREW PENNOCK'S second run gained him an eighth place in his first NCAA slalom. Ben finished a disappointing 15th. David had one of the fastest second runs of the day, but his earlier fall was too much to overcome. He finished 31st. Combining scores for men's and women's alpine and Nordic gave Utah a national championship. UVM came in second. Dartmouth ninth. But you rarely hear skiers speak of team totals. Teammates are there for friendship, to push you to your best. Ski racing remains a personal duet one racer, one mountain.

Ben is back at Dartmouth this year, pursuing a combined master's in business and engineering. He has made peace with his dreams. He has thrown himself into his studies as he did a race course. He wants to start his own company. "I want to still take risks," he says. During the summer he tutored physics and engineering in California and fell in love with surfing. Still, he says, "I'm going to miss traveling with the team. I'm going to miss the friendships." Vici and Win face the first winter in two decades they have not planned around a child's ski races. "It's been so much a part of our lives," says Vici. "It's going to be hard."

David Viele is healthy. On paper, under a complicated international scoring system, he is ranked about 150th in the world, two seconds behind the fastest European champions. "This is my year to start rebuilding my international standing," he says. Now he wants it all: Dartmouth and the Olympics. He has two seasons left with Peter Dodge and he thinks Dodge can get him to Salt Lake City in 2002. His sister, Jenny '00, races with the women's varsity. Dartmouth is home. He has a new roommate, Andrew Pennock. Andrew finished just seconds behind David on the run up Moosilauke. It is Andrew who holds the record for jumping on and off Peter Dodge's box 120 times. "If you thought Ben and I were competitive..." David laughs. "Andy and I are ten times more competitive. We're going to be something to see this year."

A skier tripos the Starting wand. An enntire lifetime is reduced to hundredths of a second and a single thought:"Go fast"

Alpine coach Bruce Lingelbach (top) gives Green skis an edge. Before the start, Ben Robinson (right) trudges in with the competition.

Ben blasts past a gate this time. (Below) Coach Peter Dodge, left, guides the lineage: Robinson, Viele, and Pennock.

"There's so much adversity. Ski racing is aboutattrition."David Viele '98(below)

"I know parents who when their child comes down, they turn away. I know parents who just can't go to a race." Winfield Robinson '60 (below, with wife Vici)

Mel R. Allen is a senior editor at Yankee magazine

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

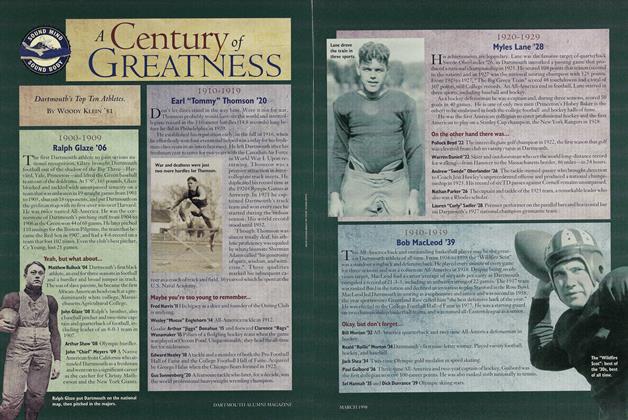

FeatureA Century of Greatness

March 1998 By Woody Klein '51 -

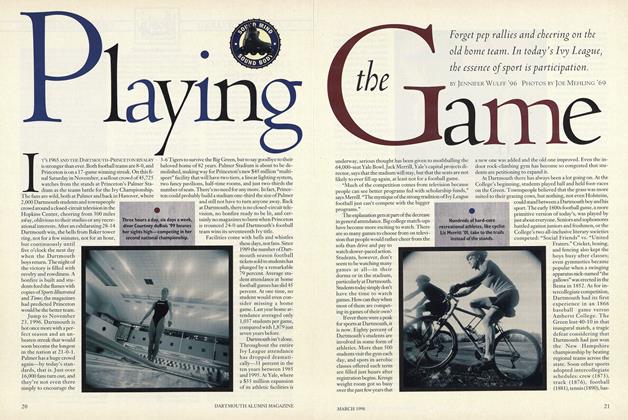

Cover Story

Cover StoryPlaying the Game

March 1998 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

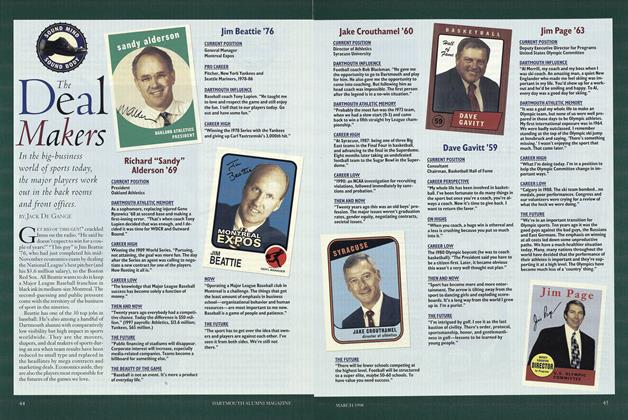

Feature

FeatureThe Deal Makers

March 1998 By JACK DE GANGE -

Feature

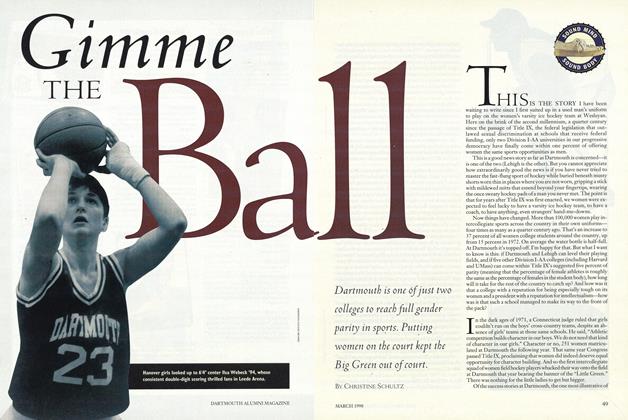

FeatureGimme the Ball

March 1998 By Christine Schultz -

Feature

FeatureOld School New School

March 1998 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureThe Good Sport in Me

March 1998 By Regina Barreca '79

Features

-

Cover Story

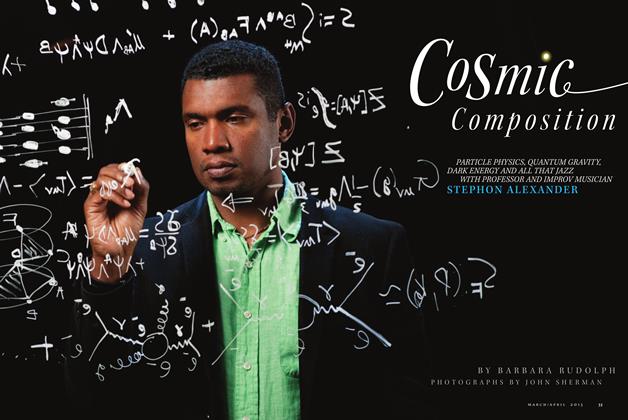

Cover StoryCosmic Composition

Mar/Apr 2013 By BARBARA RUDOLPH -

Feature

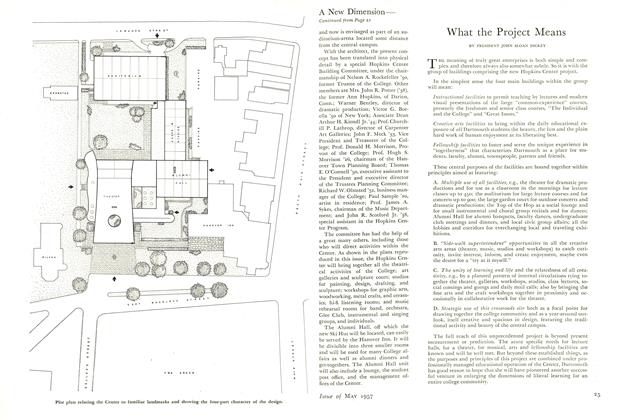

FeatureHow Green Is Squaw Valley

February 1960 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO BECOME A LAWYER

Sept/Oct 2001 By DANIEL WEBSTER -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO GREEN UP YOUR KITCHEN

Jan/Feb 2009 By JENNIFER ROBERTS '84 -

Feature

FeatureJourney's End: The Assyrian Reliefs at Dartmouth

SEPTEMBER 1985 By Judith Lerner -

Feature

FeatureWhat the Project Means

MAY 1957 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY