Dartmouth is one of just twocolleges to reach full genderparity in sports. Puttingwomen on the court kept theBig Green out of court.

THIS IS THE STORY I have been waiting to write since I first suited up in a used man's uniform to play on the women's varsity ice hockey team at Wesleyan. Here on the brink of the second millennium, a quarter century since the passage of Title IX, the federal legislation that outlawed sexual discrimination at schools that receive federal funding, only two Division I-AA universities in our progressive democracy have finally come within one percent of offering women the same sports opportunities as men.

This is a good news story as far as Dartmouth is concerned it is one of the two (Lehigh is the other). But you cannot appreciate how extraordinarily good the news is if you have never tried to master the fast-flung Sport of hockey while buried beneath musty shorts worn thin in places where you are not worn, gripping a stick with mildewed mitts that extend beyond your fingertips, wearing the once sweaty hockey pads of a man you never met. The point is that for years after Title IX was first enacted, we women were expected to feel lucky to have a varsity ice hockey team, to have a coach, to have anything, even strangers' hand-me-downs.

Now things have changed. More than 100,000 women play intercollegiate sports across the country in their own uniforms four times as many as a quarter century ago. That's an increase to 37 percent of all women college students around the country, up from 15 percent in 1972. On average the water bottle is half-full. At Dartmouth it's topped off. I'm happy for that. But what I want to know is this: if Dartmouth and Lehigh can level their playing fields, and if five other Division I-AA colleges (including Harvard and UMass) can come within Title IX's suggested five percent of parity (meaning that the percentage of female athletes is roughly the same as the percentage of females in the student body), how long will it take for the rest of the country to catch up? And how was it that a college with a reputation for being especially tough on its women and a president with a reputation for intellectualism how was it that such a school managed to make its way to the front of the pack?

In the dark ages of 1971, a Connecticut judge ruled that girls couldn't run on the boys' cross-country teams, despite an absence of girls' teams at those same schools. He said, "Athletic competition builds character in our boys. We do not need that kind of character in our girls." Character or no, 251 women matriculated at Dartmouth the following year. That same year Congress passed Title IX, proclaiming that women did indeed deserve equal opportunity for character building. And so the first intercollegiate squad of women field hockey players whacked their way onto the field at Dartmouth that year bearing the banner of the "Little Green." There was nothing for the Little ladies to get but bigger.

Of the success stories at Dartmouth, the one most illustrative of the hard-fought rise in women's sports belongs to the basketball program. "When I started as a coach here in 1976," says Chris Wielgus I had no office. I had a drawer in the training room. I was a phys-ed teacher working part-time at night. We always had the last practice time slots, after the men's junior varsity and freshmen teams. We had no courtesy cars, no bus. I had one assistant; the men had two "

That was the case across the country in the seventies. If women got uniforms and coaches made 50 cents on the dollar, they were lucky. That was all they got.

Back in the early eighties we got a core of women who completely turned the game around," says Wielgus. "We started winning in the Ivies, and people started coming out to watch. We had unbelievably good teams and games against top-ranked competition. You can't underestimate how important winning is."

In the eighties women's skills improved, but their resources did not. Dartmouth's women won the Ivy title four years in a row, but there were no significant raises for female coaches, little publicity for their teams, no recruiting for their improvement.

Wielgus left college coaching in 1984, was off the scene for seven years, and is now back at the helm. "I didn't miss a beat, she says. But she had missed a crucial step forward. "If you follow the money, the money follows the courts," she says. "And it wasn't until 1988, when the Equal Rights Restoration Act put punch into athletics rulings, that things really changed. Before that, Title IX said you'd risk losing federal funding, but the cases were hard to try. You had to go through the civil rights bureaucracy, and schools were generally just slapped on the wrist if they didn't comply. Now, women can file for damages."

Among the first women to file for damages were nine gymnasts at Brown, who sued the university in 1992 for cutting funding for both women's gymnastics and volleyball teams. Brown argued that funding had also been cut for two men's teams as part of a campus-wide austerity program, and that it offered the same number of varsity sports for women as it did men. As that case entered the court system, the Dartmouth women's Softball club filed a 26-page complaint with the federal education department, citing discrimination and requesting that the team be funded as a varsity program.

While many schools around the country sat back and waited to see how the Brown case would be decided before investing in women's sports programs, Dartmouth listened to the women and acted. In the fall of 1992 athletic director Dick Jaeger '59 ordered a gender equity study. The following spring a long-range plan called for increasing the number of funded women's teams to 17 equal to the number of men's and for making the percentage of female athletes equal to the percentage of female undergraduates.

Meanwhile, Brown, supported by the American Council on Education, 60 universities and colleges, and 49 members of Congress, appealed its case all the way to the Supreme Court. In 1997 the high court found the university in violation of Title IX. The schools that waited for that decision are scrambling now to get their gymnasiums in order. Dartmouth, on the other hand, has become a national model for compliance.

"The right people were in the right place, and they knew it was the right thing to do," says associate athletic director Josie Harper. Contrary to alumni concern that James Freedman wouldn't give athletics institutional support, the president got the proverbial ball rolling by insisting that Title IX compliance be a priority. "If Dick Jaeger and Jim Freedman hadn't said, 'Find a way to make it happen,"' says Harper, "it wouldn't have gotten done."

It got done by shuffling resources. The contributions of the "Friends" of men's teams were combined with those of the women's teams, then split evenly between the sexes. After some initial resistance, coaches of financially sound teams saw it was the way to go. Any coach who wanted money earmarked just for his or her own team could still go out and raise separate funds, but other contributions would be shared. "When we first talked about merging the Friends' contributions, we were admonished by men who said that a lot of men wouldn't contribute," says Jaeger. "But we've been pleasantly surprised, and have even seen increases."

The shift has meant that more money now goes toward recruiting women athletes. It means better contracts and salaries for head coaches in women's ice hockey and golf. It means a new intern for publicizing women's events, and a bigger meal and room allowance for traveling teams. It means that women coaches no longer make half of what men do.

Does all this mean that, thankfully, the athletics department can turn to other things? "No," says Dickjaeger. "We can't look away. There's a whole spectrum of changing needs, and we have to stay fair across the board."

The result of Dartmouth's commitment, by any measure, has been worth it. The percentage of female athletes during the four years following the gender-equity study climbed nearly ten percent, to the point that in 1995-96, females made up 47 percent of the undergraduate body and 47 percent of the athletes. Women's basketball games have become so popular that the team can charge admission and have standing-room-only at Harvard games. "For years we had to fight to get our scores in the paper," says Coach Wielgus. "People said no one reading the sports page would care about women's basketball, but they do." Her teams have been to the NCAA national tournament, been on TV, been Ivy champions 11 years out of 18. And something more important has happened. The women players sign autographs after every game now. They have photo-op days. They meet with younger athletes in local schools around the Upper Valley. When the next generation of female athletes gets to college, it will have not only uniforms free of male perspiration, but models and memories of female inspiration as well.

"It has been slow going to get this far," says Wielgus, "but the more you get, the more you get used to. And no matter how long it takes the rest of the country to catch up, it won't ever go backwards from here."

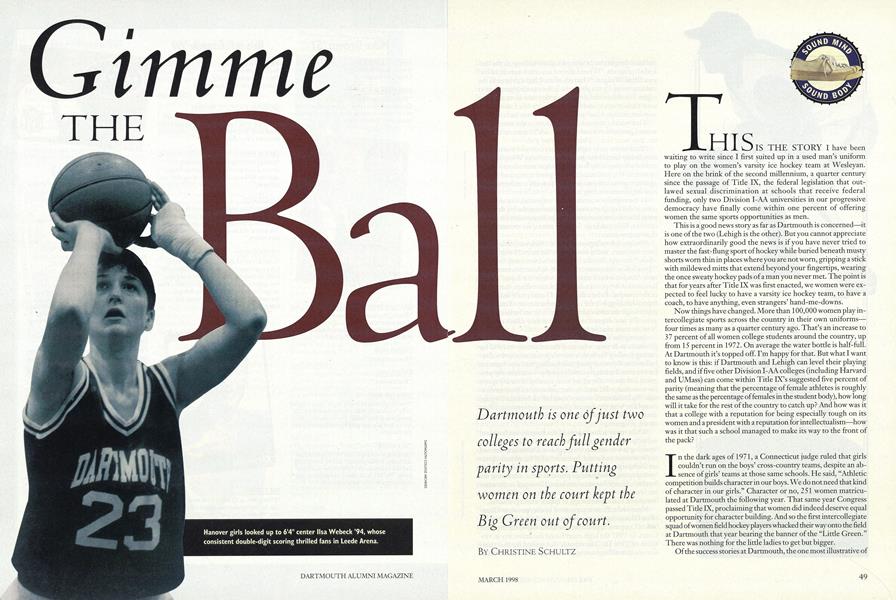

Hanover girls looked up to 6'4" center llsa Webeck '94, whose consistent double-digit scoring thrilled fans in Leede Arena.

Lauren McQuade '97 and the varsity Softball team won before they played. Off the field, the team's squeeze play put the College in compliance.

Title IX was just six years old when goalieKaren Kurkjian '78 blocked slapshots in ahand-me-down men's uniform.

"In the eighties women's skills improved, but their resources did not'

"In 1995-96 females made up 47 percent of the student body and 47 percent of the athletes."

Writer CHRISTINE SCHULTZ has traded pond hockey in NewHampshire for running and playing squash in Mississippi.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

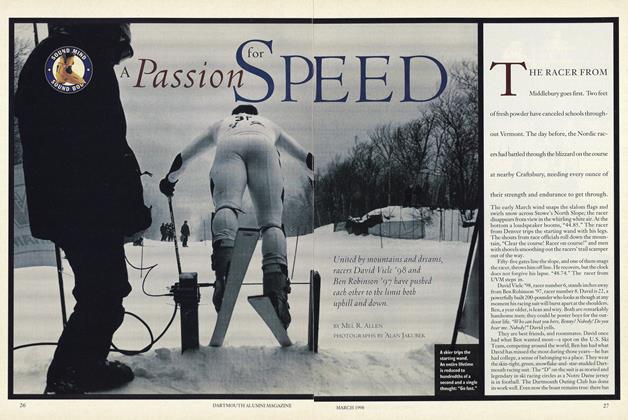

FeatureA Passion for Speed

March 1998 By Mel R. Allen -

Feature

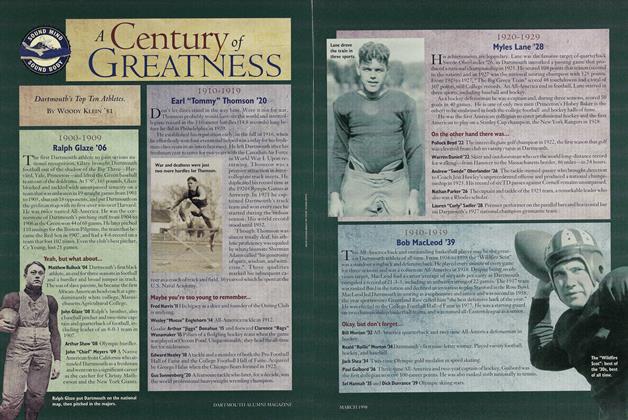

FeatureA Century of Greatness

March 1998 By Woody Klein '51 -

Cover Story

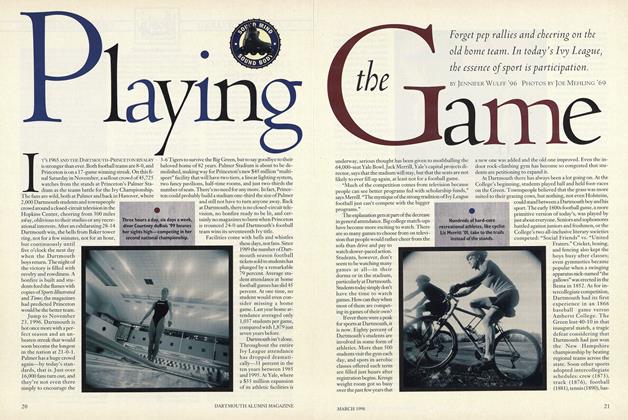

Cover StoryPlaying the Game

March 1998 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureThe Deal Makers

March 1998 By JACK DE GANGE -

Feature

FeatureOld School New School

March 1998 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureThe Good Sport in Me

March 1998 By Regina Barreca '79

Christine Schultz

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Purpose Gap

MARCH 1990 -

Feature

FeatureAN ATHLETIC SUMMING UP

JUNE 1967 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO BUILD THE HOMECOMING BONFIRE

Jan/Feb 2009 By DANIEL SCHNEIDER '07 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWhy Don't You Say Anything?"

APRIL 1997 By Davina Begaye Two Bears '90 -

Feature

FeatureGOTHAM GAMBIT:

December 1956 By KIMBALL FLACCUS '33 -

Cover Story

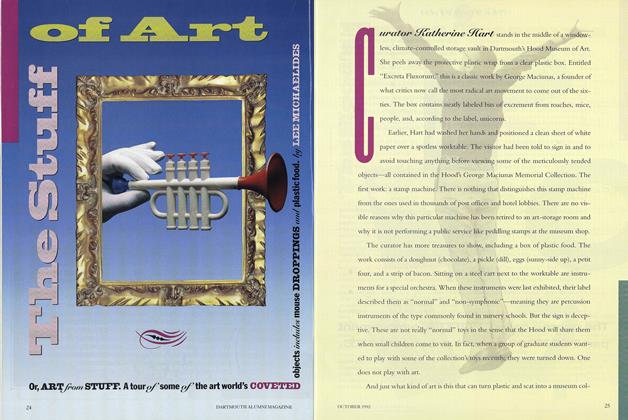

Cover StoryThe Stuff of Art

October 1992 By LEE MICHAELIDES