In 1941 a meeting in Nazi occupied Copenhagen took place between Werner Heisenberg, the brilliant physicist heading Germany's atomic research effort, and his mentor, Danish physicist Niels Bohr. World War II had made the two men, who had once been as close as father and son, into political enemies. What they said to each other at the meeting remains a mystery. All that is known is that it ended badly.

History tells us that Bohr eventually escaped from Copenhagen and contributed to the development of the atomic bomb at Los Alamos.

Heisenberg remained in Germany. Is it possible that he sabotaged Hitler's cause on ethical grounds, as he claimed after the war? And what of Bohr? Did he make the right ethical choice by helping the United States build the bomb?

Award-winning playwight Michael Frayn tackled those questions in his new play Copenhagen, and Dartmouth's Math Across the Curriculum project staged a bench reading of the play and a panel discussion in February. From across the curriculum, in the English department, came the reading's director, Peter Saccio, and its Heisenberg James Heffernan. Laurence Dasvies of comparative literature and Bonnie Wallin a curator in Rauner Library, read as Bohr and his wife.

Central to the play's conflict was the question: Is it morally right in wartime for a physicist to work on nuclear arms? That point was debated following the reading by a panel that included Heisenberg's son Jochen a professor of nuclear physics at M.I.T. and the University of New Hampshire.

"I believe the record of his own report," said Heisenberg. His father maintained that resistance can take different forms, and in his own case the complexities of wartime Germany made a simple explanation impossible. As the play suggests, without knowing the ethical quandaries and choices available to Heisenberg, it isn't possible to judge whether he was a hero or a villain.

Heinsenberg claimed that by maintaining control of the regime's atomic research he kept the bomb out of Nazi hands.

"I believe that is true," said journalist and fellow panelist Thomas Powers, author of Heinsenberg's War: The SecretHistory of the German Bomb. "The answer lies not in what he said, but what he did. The reason there was no [German] bomb is his doing."

Panelist David Kaiser '93, a Ph.D. in physics and the history of science, posed a key question. Why was there no German bomb program? Kaiser cited several historic facts, including a comparison with the United States, where the equivalent of three cities were built to create the bomb. Kaiser asserted that those resources were unavailable in wartime Germany.

Most of the attendees who packed 105 Dartmouth stayed till the end of the three-hour exploration. The consensus: Heisenberg botched the job- on purpose.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

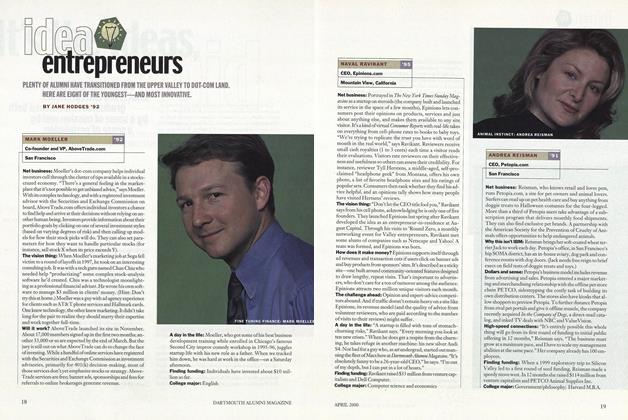

FeatureIdea Entrepreneurs

April 2000 By JANE HODGES '92 -

Feature

FeatureIt’s the Ideas, Stupid

April 2000 By KEITH H. HAMMONDS ’81 -

Feature

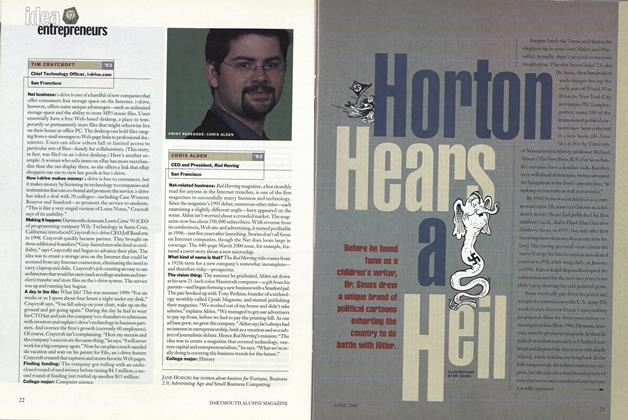

FeatureHorton Hears a Heil

April 2000 -

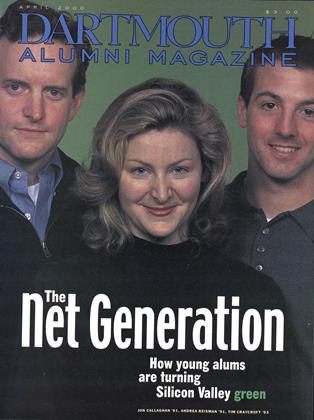

Cover Story

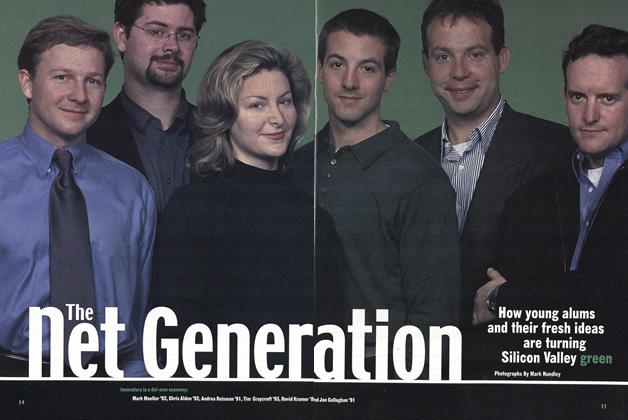

Cover StoryThe Net Generation

April 2000 By Jane Hodges ’92 -

Article

ArticleThe Power of Philanthropy is the Power of Growth

April 2000 -

SYLLABUS

SYLLABUSRewriting Violence

April 2000 By Courtney Cook Williamson ’93