It’s the Ideas, Stupid

A liberal arts education is all about ideas.

April 2000 KEITH H. HAMMONDS ’81A liberal arts education is all about ideas.

April 2000 KEITH H. HAMMONDS ’81A LIBERAL MIS EDUCATION—ft DARTMOUTH EDUCATION—IS ILL ABOUT IDEAS. AND IN THE INTERNET ECONOMY, ALMOST ANYONE WITH A GOOD IDEA HIS A SHOT AT SUCCESS.

The Internet is about ideas. Yes, it is about technology, too. The Net is, after all, a massive, ever-shifting electronic tapestry, billions of lines of software code layered atop an infinite network of computers linked by complex telecommunications switches and routers. If any of that stuff fails, Amazon.com ships your CD order to Belarus instead of Sheboygan.

But the Internet is mostly about ideas, about notions that explode our familiar models of commerce and community. What is powerful about Amazon is not so much its Web-based customer interface or its fulfillment logistics systems—although those are way cool—but, simply, the proposition that the Internet can be harnessed to enhance the consumer experience. Technology enables the idea, the idea creates value.

A liberal arts education—a Dartmouth education—is about ideas. Dartmouth is a factory that mints idea entrepreneurs, graduates emboldened both by a sense of mission—the notion that they should use their talents to effect change—and by a sense of permission that says they can actually pull it off. And, as the eight young alums profiled on the next few pages demonstrate, the combination of creativity with purpose is leading to all sorts of new business models.

So it is that Dartmouth grads have joined the Internet land rush, feeding the volatile craziness that grips Silicon Valley and helping to transform the very nature of entrepreneurship. It is a time of cacophonous opportunity for idea entrepreneurs: Since no one really knows where the Net is headed, nearly any idea is viable. To ignore an idea is to risk missing out on the future. "There are tens of thousands of little ideas bubbling toward the surface," says Gib Myers '64, managing partner of the Mayfield Fund, a top venture-capital firm in Menlo Park, California. "Some of them involve a new application insight or a strategic relationship that no one else has thought of. Boom! They're on the map."

Consider that explosive dynamic in light of previous generations of technology entrepreneurs. Both Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard, who fashioned a resistance-capacity audio oscillator in their famous Palo Alto, California, garage in 193 8, were electrical engineers out of Stanford. Bob Noyce and Gordon Moore were circuit geeks. They founded Intel in 1968 to make better memory chips before stumbling onto the microprocessor. Silicon Graphics, Oracle, Digital: these companies, founded by technologists, thrived by producing great, but mostly incremental, technological advances.

The Internet world still has its gearheads, such as Amazon's Jeff Bezos and the Yahoo! guys, among others. Yet a typical e-commerce startup these days relies on three people: A generalist CEO—the idea person—a marketing veep to grab eyeballs, and a finance wiz to score funding. Some venture capitalists actually discourage companies from hiring pricey tech talent early in the game. The Internet itself, after all, provides the essential technology backbone; other software can be bought off the shelf or slapped together by a few contract programmers.

Rather than according value to technology per se, the market accords value to the quality of the idea (will it work?), to speed (will it work quickly?) and to chutzpah (can you make it work?). "On the Net, you only have 10 percent of the information you need, in a world that's moving incredibly fast," says Gregory Slayton '81, CEO of Click Action Inc., a Palo Alto company that provides Web-based marketing solutions. "That puts a huge premium on judgment and guts."

What a wildly democratic notion. On the Internet, anyone has a shot at success. What's more, the Silicon Valley machine, an extraordinary network of money, advice and talent, gives young entrepreneurs license to take that shot. "For great ideas, there are no barriers to entry," says David Kratz '79, whose public relations firm now derives half its business from Net companies such as Deja.com and etown.com. Credentials don't count for much—except the credential that says you've scored big before. Connections matter—and it doesn't hurt that Dartmouth breeds obsessive networkers—but a good Internet idea will make its own connections.

So ideas, and idea capitalists, have poured onto the Net. Five years ago, while most of their classmates hustled to interviews with management consultants and investment banks, 9 percent of Tuck graduates headed for California. This year, more than 17 percent will go. Likewise, some 200 Net devotees, including 50 of Tuck's M.B.A. students, joined the school's first EForum networking gathering in Silicon Valley last December cember. Another 350 showed up for a January eForum in Boston (see related story page 8).

The Internet world is desperate for such people to fuel the growth machine. It craves energetic, idea-driven movers who can analyze problems, embrace risk and devise solutions—and who, not incidentally, will work insane hours for a crack at a big payoff. Phil Ferneau '84, director of Tuck's new outpost in Silicon Valley, vividly recalls a networking dinner in Palo Alto attended by several dot-com entrepreneurs, a bigtime venture capitalist, a national newspaper reporter and a young woman who had just quit McKinsey & Cos. to seek work in e-commerce. "After dinner, no one latched onto the venture capital partner or the reporter. They all scrambled to convince the McKinsey woman to come interview at their firms," he says. "Human capital was in demand, not finance or publicity."

Such is the opportunity. The downside: In an idea-based economy, the fuel comes from everywhere. Colleges and business schools all over are spewing out Net entrepreneurs. Even high schools are breeding them. "This is happening all over the world," says the Mayfield Fund's Myers. Ideas are as manifold as the human imagination allows. So the competition is as intense as the business world has ever seen.

And the rewards, ultimately, are elusive. Most ideas sputter. Most startups fail. For every Internet high-flier whose concept captures the public imagination, and whose initial public offering creates sudden, outrageous wealth, there are hundreds or thousands getting by on credit cards and fumes. Some endure, as long as hope endures. Others abandon the chase.

Yet all tie while, more will join in, from Dartmouth and beyond. The Internet's promise to change everything will captivate and entice. The idea boom will rush on.

Dartmouth is a factory that mints idea entrepreneurs, graduates emboldened both by a sense of mission and by a sense of permission.

Keith H. Hammonds is a senior editor at Fast Company magazine. He lives in New York City.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

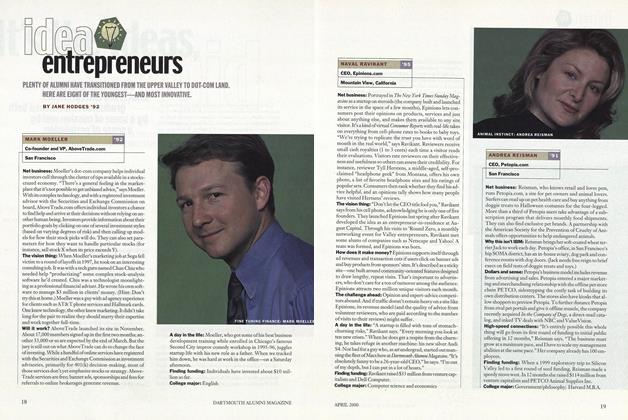

FeatureIdea Entrepreneurs

April 2000 By JANE HODGES '92 -

Feature

FeatureHorton Hears a Heil

April 2000 -

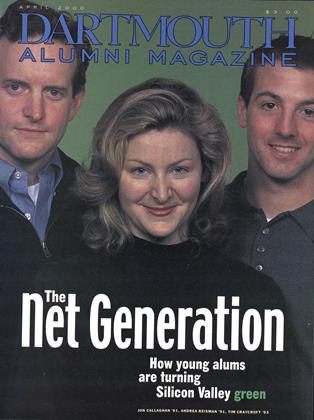

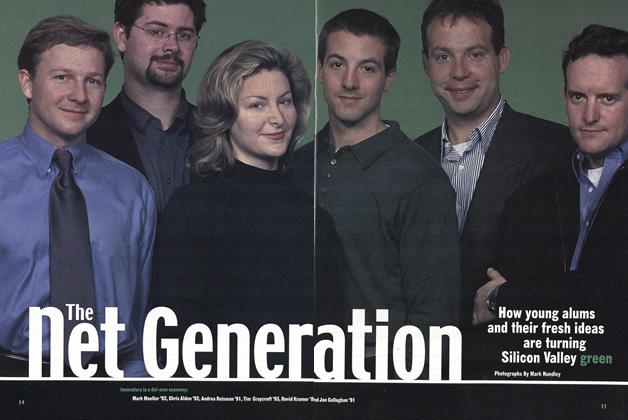

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Net Generation

April 2000 By Jane Hodges ’92 -

Article

ArticleThe Power of Philanthropy is the Power of Growth

April 2000 -

SYLLABUS

SYLLABUSRewriting Violence

April 2000 By Courtney Cook Williamson ’93 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1990

April 2000 By Jeanhee Kim, Sanda Lwin, Ramzi Nemo

Features

-

Feature

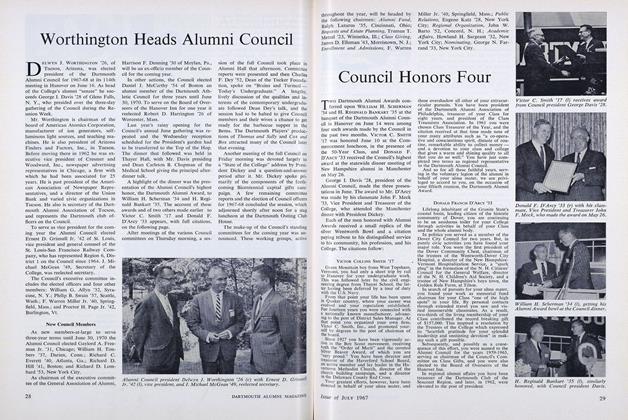

FeatureCouncil Honors Four

JULY 1967 -

Feature

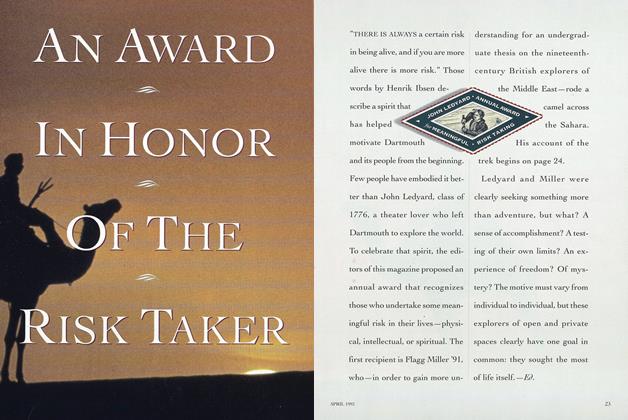

FeatureAn Award In Honor Of The Risk Taker

APRIL 1992 -

Feature

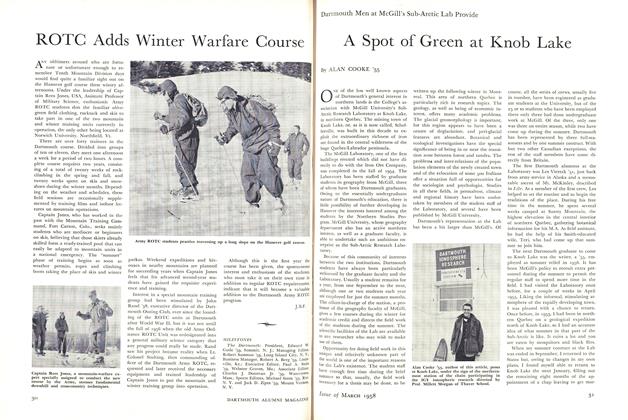

FeatureA Spot of Green at Knob Lake

March 1958 By ALAN COOKE '55 -

Feature

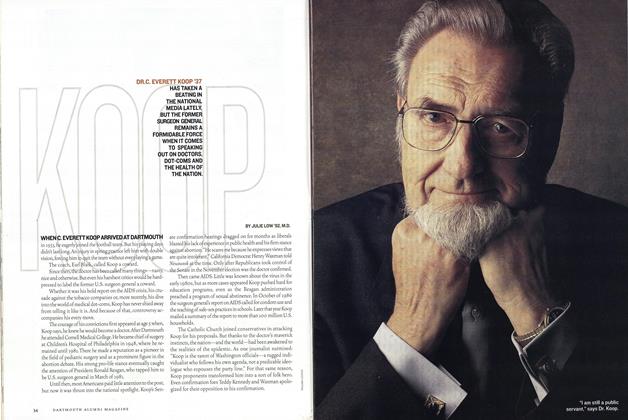

FeatureKoop

June 1992 By C. Everett Koop '37 -

Feature

FeatureEleazar Wheelock and the Dartmouth College Charter

DECEMBER 1969 By JERE R. DANIELL II '55 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryKoop

Jan/Feb 2001 By JULIE LOW ’92, M.D.