Rewriting Violence

A writing class finds that the pen is made mightier by the sword.

April 2000 Courtney Cook Williamson ’93A writing class finds that the pen is made mightier by the sword.

April 2000 Courtney Cook Williamson ’93A writing class finds that the pen is made mightier by the sword.

Professor Don Sheehan kicks off his two-term freshman composition course (English 2 and 3: "Reading and Writing in the Arts and Sciences") in a most unusual way. He asks students to remember violence—to dredge up their memories of bullies and bullying, of beatings inflicted or experienced, of anger, of isolation, of rape. He does this, in spite of their reticence and obvious discomfort, because he believes violence is our most common denominator, that it is a concept to which almost any academic discussion will inevitably return and—disturbingly—that students just starting at Dartmouth have already encountered more violence, emotional and physical, than any other human experience. Sheehan's call to remember violence is not only a means of dispelling one of the most basic myths about violence-that violent behavior happens only to other people. He also sees it as the most direct way to the introspection and self-understanding that are critical to clear thinking and writing.

Sheehan believes students can't become writers and thinkers until they've discovered what he calls their "personhood." He feels that students must think far more deeply and bravely to write well. "Every part of your being is involved in writingthere have to be changes on all levels," he says. To foster that, Sheehan requires students to work at that inquiry in daily journals. In early entries, students fill their notebooks with outpourings about violence-fights with fathers, bouts with bulimia and anorexia, difficult breakups, cruel teammates. By the end of the course students are writing more formal, researched compositions.

Along the way they are guided by Sheehan's deliberate, if idiosyncratic, choices of readings. Even the foundation text for the course is a bit unorthodox. It isn't about composition or literature. It's an anthropological book, Violence Unveiled, by Gil Bailie. Taking up French anthropologist Rene Girard's theory that scapegoating underscores much of violence, Bailie contends that human beings actually thrive on their habit of blaming others for their suffering. He argues that most of the world's cultures ritualize scapegoating, endowing violence toward an other with moral fervor to achieve cultural order. By perfectly describing the one-upmanship that has defined, for example, the Cold War or the conflicts in Bosnia or Kosovo, Bailie articulates the unifying effects of the practice of revenge. It is, he says, a "mechanism for preserving culture that is as old as culture itself."

Sheehan then helps his students apply this view of the pervasiveness of violence to a sweeping range of literature. The class reads Ursula Hegi's novel of the Holocaust, Stones From the River, which explores the sufferings of a young dwarf in Nazi Germany, and the journalist Peter Maass' collection of essays, Love Thy Neighbor: A Storyof War, which chronicles his observations of war-torn Bosnia. Sheehan also introduces several of Shakespeare's sonnets, which he believes "uniquely reveal what is perhaps one of our most serious relational afflictions: erotic envy." In the sonnets, he says, we can see the übiquity—and personal familiarity—of this "affliction," as well as the emotionally violent behavior it engenders. Sheehan also exposes his students to a biblical perspective on violence: the Gospel ofMark, the story of how Jesus tried to counteract violence by offering love rather than revenge towards oppressors.

During the second term of the course, the students continue to explore violence-and possible solutions to it. They receive a truly epic dose when they read Fyodor Dostoyevsky's The Brothers Karamazov. The characters Father Zosima and Alyosha Karamazov offer what Sheehan calls "kenotic," or self-emptying, love to the suffering and angry people around them. Through them, Dostoyevsky holds out the delirious possibility of a life free from violent influence. The novel offers lessons both literary and personal, says Sheehan. Dostoyevksy suggests that solving the world's addiction to violence isn't about retribution or logic, but that it is about offering love—unabashed love—in spite of it. Shakespeare's The Winters Tale offers another example of violence solved by Kenotic love. In this play, King Leontes, whose envious rage drives him to order the death of his daughter and to banish his queen, comes to an understanding of love through the patient mercy and guiding wisdom of his wife's confidante Paulina. In the first flush of his experience of this love Leontes confesses, "No senses of the world can match/The pleasures of that madness."

Ultimately, the success of the course depends on the students' ability to see the connection between searching introspection-painful though it may be—and literate expression. By the last day of the class, it is the hopeful and peaceful words of Alyosha Karamazov that are its fitting epitaph. "Let us never qforget how good we once felt here, all together, united by such good and kind feelings as made us...perhaps better than we actually are."

Courtney Cook Williamson '93 was ateaching assistant in Professor She eh an's courselast year. She is a freelance writer living in Sydney,Australia.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureIdea Entrepreneurs

April 2000 By JANE HODGES '92 -

Feature

FeatureIt’s the Ideas, Stupid

April 2000 By KEITH H. HAMMONDS ’81 -

Feature

FeatureHorton Hears a Heil

April 2000 -

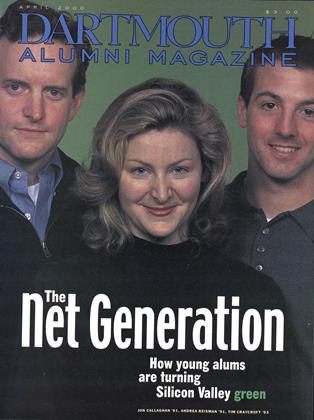

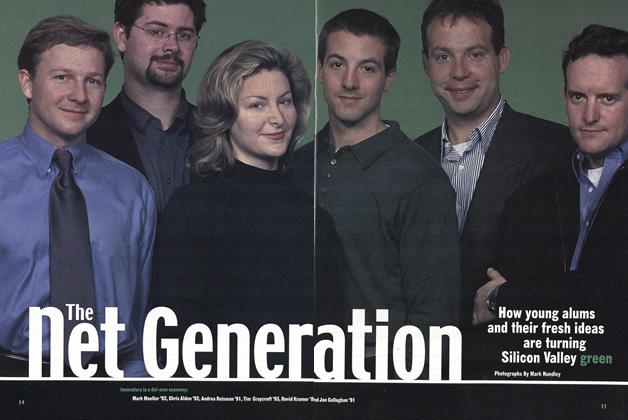

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Net Generation

April 2000 By Jane Hodges ’92 -

Article

ArticleThe Power of Philanthropy is the Power of Growth

April 2000 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1990

April 2000 By Jeanhee Kim, Sanda Lwin, Ramzi Nemo