The Places You Can Go

The unique vision of James Reynolds, class of 1890, lets recent graduates study anything, anywhere.

May/June 2001 Dustin Rubenstein ’99The unique vision of James Reynolds, class of 1890, lets recent graduates study anything, anywhere.

May/June 2001 Dustin Rubenstein ’99The unique vision of James Reynolds, class of 1890, lets recent graduates study anything, anywhere.

AS THE HORIZON HEAVED UP AND down with each successive wave, our destination—Isla St. Fe—disappeared beyond a wall of water. Behind us, the towering summit of St. Cruz's volcano lay hidden in a mass of clouds that seemed to reach out after the boat, following us on our journey to the deserted island that would be my home for more than four months. As I gazed back in the distance, an enormous splash caught my attention.

"Manta," shouted the captain.

Manta ray. I stared at the wisps of whitewater where the beast had just landed and could only imagine what other natural wonders I would see during my stay in one of the worlds true ecological paradises: the Galapagos Islands.

It was hard to believe that just three days before I had been sitting on the Green listening to a parade of Commencement speakers telling me to go out and make my mark on the world, to take my education and make a difference. As most of my friends left the Hanover plain for corporate jobs, I boarded a plane bound for Ecuador to begin a year of independent research on a desolate island.

I was the latest of 316 alumni to benefit from the vision of James Burton Reynolds, class of 1890.

Long before the first Dartmouth Foreign Study Programs, Reynolds established one of the earliest private scholarships in the country to send recent graduates to the far reaches of the globe to further their education. A lifetime of public service (as secretary of the Massachusetts Republican State Committee, assistant secretary of the Treasury under President Theodore Roosevelt, member of the Tariff Board under President Taft and advisor to President Coolidge) had taught Reynolds the importance of understanding world affairs. He was an idealist who saw the future of America entwined with the rest of the world, and he recognized the need for able young men who could lead their country into this new era.

He turned to his alma mater to find such men.

In 1945 Reynolds met incoming Dartmouth President John Sloan Dickey '29, a former State Department liaison on reciprocal trade agreements, and found that, in the words of Dickey himself, they "shared a common concern with international affairs." As Dickey later recalled, they spoke of the "importance of bringing American higher education to bear more directly and pervasively on the need of this country to develop the capacity for leadership in international affairs."

And so, upon his death in 1948, Reynolds left the College $325,000, twothirds of his estate, to begin a program of scholarships that would train Dartmouth graduates to think internationally.

The stipulations for the award were simple: Recipients had to hold a Dartmouth degree and want to study abroad. The scholarship was for graduating seniors or recent graduates, preferably not more than five years out, and was to be ad ministered by a committee made up of professors, deans and College administrators. The main factors in selecting the five or six recipients each year were, and remain, per Reynolds's wishes, "the individual and the usefulness of his proposed study to him. The long-range contributions to society arising from his work is a secondary, not primary, focus." The first awards amounted to $2,000 each and were intended to cover the costs of transportation and living abroad for one year.

Though the College now has a variety of postgraduate scholarships, none really compare in scope and size to the Reynolds Scholarship, according to Susan DeBevoise Wright, a former executive secretary of the Committee on Graduate Fellowships and the wife of President James Wright. "The Reynolds is uniquely Dartmouth and continues to evolve to this day," she says. "Its recipients include some of Dartmouth's most outstanding students in the last half-century. In my tenure as the fellowships advisor I regarded the Reynolds as the Colleges Rhodes Scholarship—our winners are as good as they come, bar any scholarship, Dartmouth or otherwise."

In many ways, Reynolds's desire was much like Cecil Rhodes's dream to gather able men from around the world and send them off to Oxford to further their education and become future leaders. Most of the earliest Reynolds Scholars headed to Europe to study at Cambridge, Oxford and the Sorbonne. Of the 165 scholars who set off between 1950 and 1974, all but 11 went to Western Europe, where they immersed themselves in the arts or studied a diversity of topics such as politics, history and literature. "The real benefit to most of us was the same: a meaningful intellectual pause between the intensity of Dartmouth and the unexamined race to academic and professional achievement," explains John Marshall '71, who studied modern history at King's College with a Reynolds grant.

While the vision of the Reynolds Scholarship has changed little in the past 50 years, much has changed in its amount and application. The original 1950 annual stipend has been increased to at least $10,000, and the variety of projects and locations of study has grown dramatically. Between 1975 and 1999,55 of the 151 scholars studied outside of Western Europe, and in the past decade that number has climbed to almost 50 percent. Some continue to study at universities, but an increasing number have chosen to do independent research projects of their own design.This past year Mary Frances Brown '98 researched medieval troubador poetry in France, Kevin Findlan '99 explored organology in Scotland, Erin Fuse '99 studied ukiyo-e woodblock printing in Japan and Ellen Wight '97 researched refugees and migration in England.

For the most part, the Reynolds Scholarship has funded more projects in the humanities and social sciences than in the sciences; my proposal to study the behavioral ecology and physiology of the endemic Galapagos marine iguana was the first to receive funding for pure ecological research.

Rather than experiencing a new culture and interacting with diverse people, as Reynolds had envisioned, I was isolated on an island. I spent the days watching giant lizards forage, fight and breed and 2the nights chasing them around on slippery lava rocks overlooking precipitous cliffs to take blood samples. The Pacific Ocean was my bathtub, toilet, dishwasher, study site and grocery store all wrapped up in one. I survived on canned vegetables and tuna for months at a time, and when the January 1999 coup in Ecuador disrupted supply shipments out to the islands, I found myself dreaming of canned peas and black beans, tired of chickpeas and garbanzo beans night after night. But life was not always tough. I supplemented my diet with fresh fish and lobster, I watched manta rays hurl themselves out of the water each day and I swam amongst schools of docile hammerhead sharks.

It was a most meaningful pause before I began my race toward a Ph.D. As I spent last winter analyzing all of my data, I often found myself staring out my office window at the gray New York skies and continuous snowfall; it was a far cry from the rich blue skies and shimmering seas of the Galapagos. As I now begin the hunt for grant money to fund my upcoming dissertation research in some other exotic location, I know I will never quite have the same sense of freedom that I had last year when I could explore anything I wanted, anywhere I chose.

I can think of no better way to, as Reynolds himself said, "cap a Dartmouth education [than] with this kind of exposure to other ways of life," even if those other ways of life are for reptiles.

DUSTIN RUBENSTEIN is working towarda Ph.D. in behavioral ecology at CornellUniversity.

Alumni interested in learning more about the Reynolds Scholarship should visit the career services Web page at www.dartmouth.edu/~csrc/students/ awards_3.shtml or contact career services assistant director Marilyn Rawlins Grundy at (603) 646-2215 or marilyn.r.grundy@dartmouth.edu.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

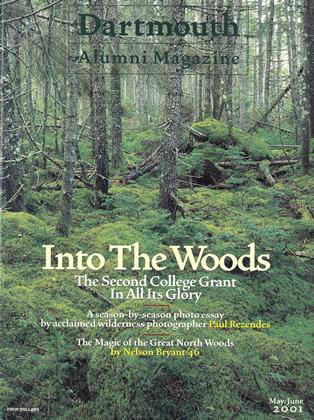

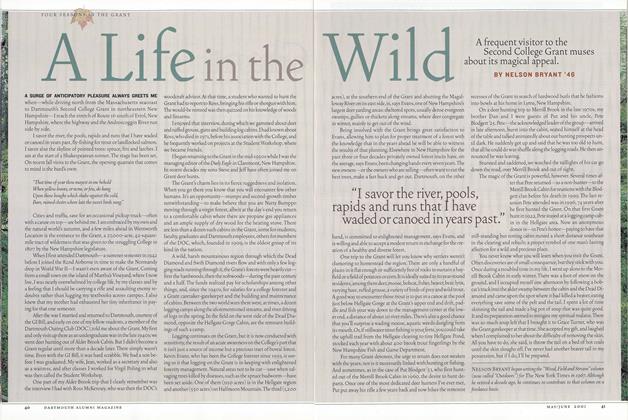

FeatureA Life in the Wild

May | June 2001 By NELSON BRYANT ’46 -

Feature

FeatureShooting the Grant

May | June 2001 By BEN YEOMANS -

Feature

FeatureVoices in the Wilderness

May | June 2001 By Jennifer Kay '01 -

Feature

FeatureTHE GREAT NORTH WOODS

May | June 2001 By Michelle Chin '03 -

Cover Story

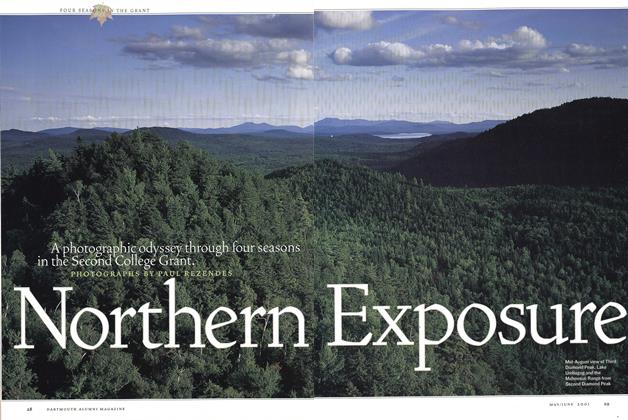

Cover StoryNorthern Exposure

May | June 2001 -

Sports

SportsThe Sporting Life

May | June 2001 By Lily Maclean ’01

Personal History

-

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYGetting the Picture

May/June 2008 By Andrew Mulligan ’05 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYHigh Fidelity

Sept/Oct 2006 By Brian Corcoran ’88 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

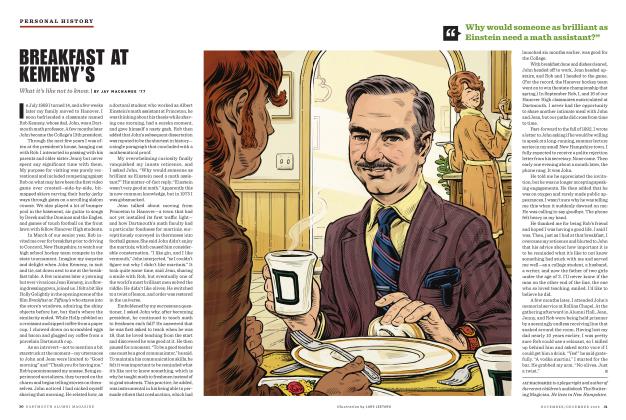

PERSONAL HISTORYBreakfast at Kemeny’s

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2025 By JAY MACNAMEE ’77, LARS LEETARU -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYBuddha on the Water

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2018 By JEREMY HOWICK ’92 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryLife In a Cubicle

Jan/Feb 2004 By Liam Kuhn ’02 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYThere and Back Again

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2016 By MARTY JACOBS ’82