Shooting the Grant

I had the job of assisting Paul Rezendes as he photographed the Grant, season by season.

May/June 2001 BEN YEOMANSI had the job of assisting Paul Rezendes as he photographed the Grant, season by season.

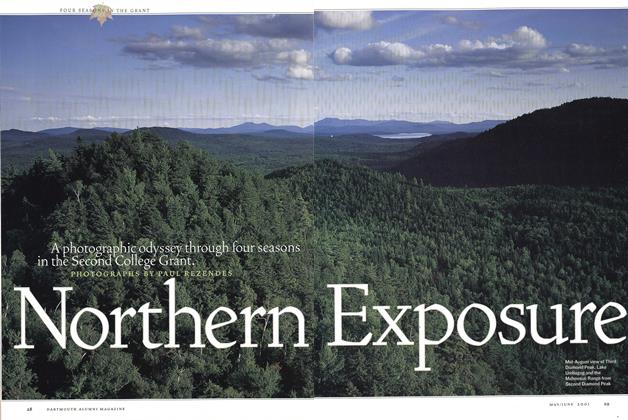

May/June 2001 BEN YEOMANSI HAD THE JOB OF ASSISTING Paul Rezendes as he photographed the Grant, season by season, for Dartmouth AlumniMagazine. Helping Paul with his work gave me a more realistic idea of the effort and resources that lie behind all those striking landscapes we see in magazines, books and calendars. Depending on the season, a day in the field could last from 4 a.m. to 10 p.m., and we would work these hours five or six days in a row. On foot we would carry 120 pounds of gear and photo equipment for miles to a remote pond or up a mountain in hopes of a good view. Sometimes we found only unfavorable light or perspective, and we returned without a shot taken.

On a typical day we'd load our photo equipment and gear into a van and head down the roads of the Grant. We would scan the sky as we drove along, looking at cloud patterns to determine the direction of our morning shoot. Patchy clouds in the east might send us west to shoot into the sun. Clear skies might find the rising sun at our backs as we waited for the Diamond Peaks to light up. From dawn until dark, our route was determined by clouds, wind and changes in the sky. Through the four seasons we scoured the Grant by foot, snowshoe and van, sometimes rewarded with a perfect shot down a river lined with conifers, other times thwarted by wind or inadequate lighting. We were always looking.

Each season had its own character and offered distinct challenges to our assignment. Summer tested our stamina with long days and short nights. The winter welcomed us with single-digit temperatures, relatively few hours of light and deep snow, which slowed our travel significantly. Many of my spring memories are a haze of black flies and no-see-ums. It seemed no matter how much of our skin we covered, they'd feast on us as we stood waiting for a cloud to pass or a momentary break in the wind.

One spring morning, overcast skies almost kept us in bed. But a slight clearing on the eastern horizon beckoned us to a prescouted spot on the Swift Diamond River. Pushing through the dew-soaked brush between road and river, we stepped out on the bank to see the glassy water reflecting the dark purple cloud mass above. We shot frame after frame (left) as the light increased and the river and clouds moved through a stunning spectrum of color until the sun at last crested the ridge.

Moments like this, when so many of natures elements came together, were rare. Rarer still were the times when we were there, in just the right spot, to capture it on film. That spring sunrise was full of the magic we were always searching for.

During the winter, many roads were unplowed. So we snowshoed our way around with the camera bags and tripod strapped to a plastic sled. One of us would break trail and the other would harness himself to the sled and play husky. Most of one day was spent this way as we headed to Sam's Lookout, an overlook above the Swift Diamond River. After two hours of hard hiking, we arrived to a fierce wind and a view obscured by trees. We ducked out of the wind, ate a quick lunch and left without taking a picture.

Another day led us up the Diamond Peaks to shoot the Mahoosuc Range to the south at sunset. Again we hiked in snowshoes, this time with the gear strapped to our backs. Grabbing tree limbs to keep from sliding back down the trail, we trudged through kneedeep snow to a lookout with a clear view. Though the view was striking, and particularly satisfying after the hike, the light and clouds did not cooperate to give us the photos we were hoping for.

As well as all the technical knowledge of photography that Paul shared with me, he taught me about making choices about a location and then letting go of the need for results. We left the peaks by starlight with no sense of frustration and no second-guessing, just gratitude for our good fortune to be working in such beauty.

"We shot frame after frame as the light increased and the river and clouds moved through a stunning spectrum of color until the sun at last crested the ridge."

Rezendes on location

Ben Yeomans is a timberframer, musician and amateur photographer. He lives in westernMassachusetts.

PHOTOGRAPHER PAUL REZENDES MADE SEVEN TRIPS and spent)} days in the Grant for this photo essay. "Shooting thereis the kind of assignment I would have designed for myself " hesays, "forme, it was an opportunity to immerse myself into a placeuntil there was an intimacy that gave of itself its inner beauty. Ithad to be experienced to be believed. For me, this work is not justa way to make a living, it is living." Rezendes, 58, is an accomplished wilderness photographer. His work has appeared in National Geographic, The New York Times Magazine and Sierra. He has also published three books and numerous calendars. A professional wildlife consultant and expert animaltracker with nearly 30 years of experience in the wilderness,Rezendes teaches outdoor workshops year-round throughout NewEngland. He lives in Athol, Massachusetts.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

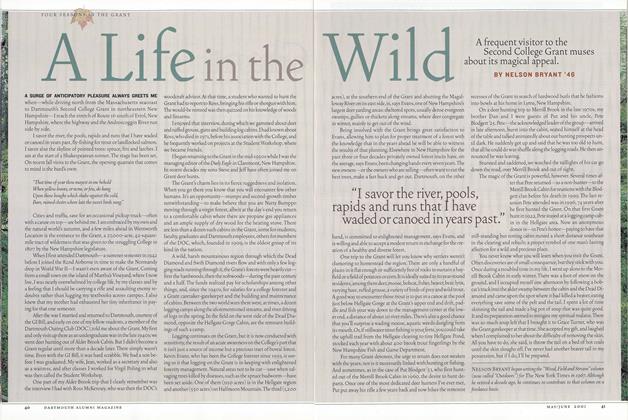

FeatureA Life in the Wild

May | June 2001 By NELSON BRYANT ’46 -

Feature

FeatureVoices in the Wilderness

May | June 2001 By Jennifer Kay '01 -

Feature

FeatureTHE GREAT NORTH WOODS

May | June 2001 By Michelle Chin '03 -

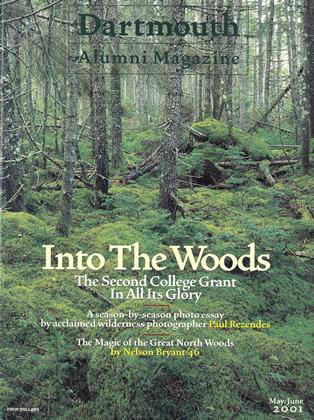

Cover Story

Cover StoryNorthern Exposure

May | June 2001 -

Sports

SportsThe Sporting Life

May | June 2001 By Lily Maclean ’01 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryThe Places You Can Go

May | June 2001 By Dustin Rubenstein ’99

Features

-

Feature

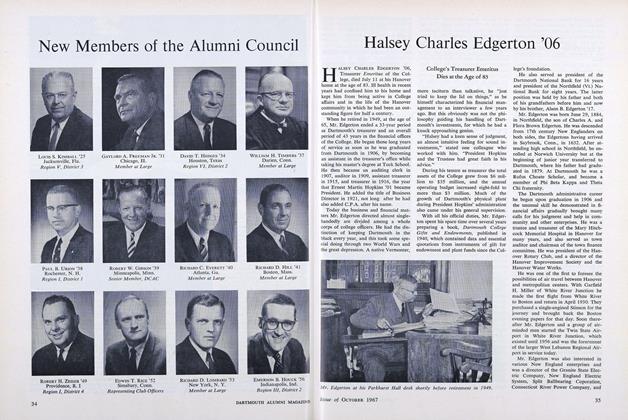

FeatureHalsey Charles Edgerton '06

OCTOBER 1967 -

Feature

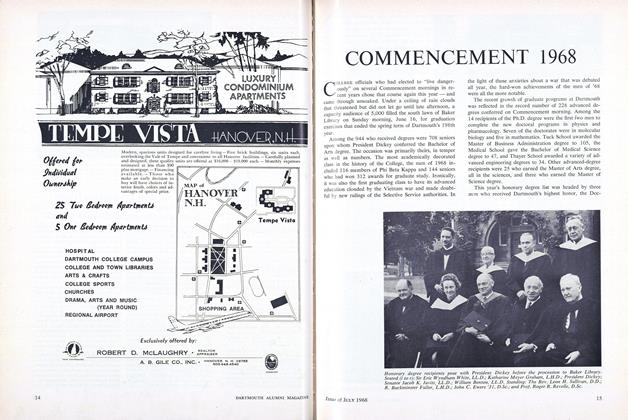

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1968

JULY 1968 -

Feature

FeaturePROBLEM SOLVER

SEPTEMBER 1990 By John Aronsohn '90 -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1972

JULY 1972 By John G. Kemeny -

Cover Story

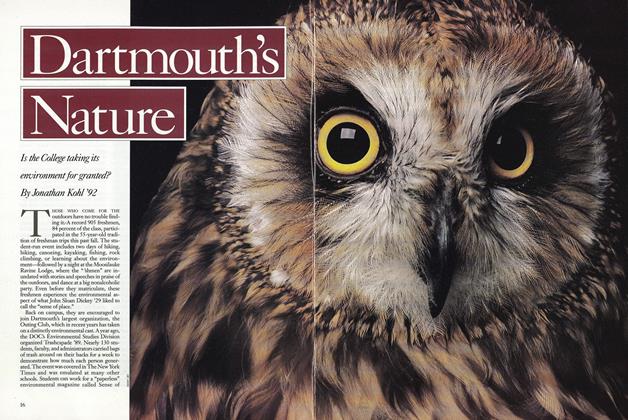

Cover StoryDartmouth’s Nature

December 1990 By Jonathan Kohl ’92 -

Feature

FeatureThe Well-Tempered Synclavier

DEC. 1977 By Woody Rothe