Pumped Up

Student athletes who lifted weights in the 1950s weren’t nuts—they were simply ahead of their time.

Jan/Feb 2007 Joel Lasky ’54 with Dan Anzel ’55 and Don Kennedy ’54Student athletes who lifted weights in the 1950s weren’t nuts—they were simply ahead of their time.

Jan/Feb 2007 Joel Lasky ’54 with Dan Anzel ’55 and Don Kennedy ’54Student athletes who lifted weights in the 1950s weren't nuts—they were simply ahead of their time.

"WHAT DO YOU GUYS THINK YOU'RE doing?"

Those words came bellowing from the far end of the upper reaches of Alumni Gym. The voice was that of swim coach Sid Hazelton, a highly respected member of what was then known as Dartmouth's physical education department. The year was 1952, and we "guys" were friends with a common interest in weightlifting. Back then anyone pumping iron was considered by the coaches to be narcissistic, deviant or, as Hazelton warned us, "Going down the road to mental illness."

In kinder moments the man referred to us as the "beef trust." We were not alone, by the way. We had three partnersin-crime: Hank Willard '54 and '55 twins Dick and Bill Blanchard. Together the six of us had found something better to do than lift alone in the confines of our dorm rooms, as an unknown number of students had done in previous years.

The crime of which we were guilty was setting up a small weightlifting area in a remote and unused corner of Alumni Gyms upper floor. We did it with the Colleges permission, of course, and stocked it with our own barbells and dumbbells because the College didn't own any.

We lifted almost daily, suffering looks of disdain from the coaches and gym instructors who occasionally wandered by. Our fellow students were more accepting. Most of them just ignored us while going about their more traditional exercise routines: climbing ropes, performing gymnastics or working out on the pommel horse, horizontal bar, parallel bars and flying rings.

In our lonely corner we experimented with various lifting movements and exercises. We followed routines published in weightlifting magazines and we learned from each other, because the manual on proper technique had not yet been written.

Back then Dartmouth's official policy excluding weight training from its conditioning programs for athletes was no different from that of any other school in America. Coaches and trainers everywhere were of a single mind: They labored underthe mistaken belief that weightlifting would make athletes "muscle bound," a condition that would seriously inhibit their movement when competing.

Fifty-plus years ago we were ahead of our time, unwitting pioneers and mavericks fostering the genesis of organized weightlifting at Dartmouth. Now in our 70s and retired, we live in different time zones but are bound together by common memories—and the Internet.

Anzel is retired from a career as a hospital executive and university professor, Kennedy is retired from the in- surance business, and I am retired from screenwriting. Despite dire predictions none of us is narcissistic or deviantand notyet demented. Weightlifting has continued to play a role throughout each of our lives.

Kennedy was 16 and in high school in a small town in Indiana when he started lifting—without benefit of training or coaching. He did it to improve his performance in football and track. At Dartmouth he was introduced to rowing and spent three years on the JV crew. Wherever he lived for years afterward he found his way to the water, competing in the heavyweight class in double, mixed doubles and quadruple sculls in meets across the United States, over distances from 1,000 meters 104.25 miles. Weight training has been an important part of his rowing success in whatever age group he has competed—and he's competed in them all. He gives it a lot of credit for his gold medals in the Arizona Senior Olympics in 2003 and 2005.

Two years ago, after a physical problem made it impossible to row on the water, Kennedy turned to indoor rowing—and has won two gold medals in Arizona's Indoor Championships. He's currently ranked 22nd in the world in the 70-to-79 age group. Anzel came to Dartmouth from Blair Academy in New Jersey, where he had captained the swim and tennis teams. Slight of build and younger than most of his classmates, Anzel knew he needed to get stronger to compete at the college level, and so joined us in our corner of Alumni Gym, disappearing any time one of his coaches appeared. His surreptitious weight lifting enhanced his performance and, in addition to captaining the tennis team, he lettered in swimming and squash.

While earning masters and doctorate degrees in California Anzel trained with several weight lifting teams and competed successfully in weightlifting and power-lifting meets at the national level. For a number of years the Amateur Athletic Union ranked him in its 165-pound division. Through it all he was motivated by more than a desire to compete. Soon after graduating from Dartmouth he was diagnosed with diabetes. Faced with a lifetime of insulin injections he set out to prove that this chronic disease would never get the better of him. He did it, fueled by the challenge of weight lifting.

Anzel s busy career put an end to his competitive lifting, but in retirement he continues to play tennis and train with weights almost daily.

For me, weight lifting was a lifelong hobby that eventually turned into a lifesaving activity. Back in high school I tried various forms of exercise, motivated by a teenage desire to increase strength and bulk up. Pumping iron worked best.

I wasn't a jock like Kennedy and Anzel, although I did try to throw the javelin at Dartmouth (the track and field coach, after watching me in practice, suggested that I find another athletic outlet). I've since been a recreational tennis player, snow and water skier and horseback rider, all the while working out with weights. Nothing has ever interfered with lifting—not two years in the Air Force or three years in law school. I continued exercising with weights into my 60s. Then came the day when I learned that being in good shape is not the same as being in good health.

At 64 my heart's mitral valve gave out. I opted for a mechanical valve replacement, followed by a six-month medically supervised rehab program. To my surprise, weight lifting was as much a part of rehab as cardiovascular conditioning—and worked so well that, 10 years later, I still pump iron three times a week at a local gym. What better testimonial could there be for the benefits of weight training?

Half a century ago we three weight lifters, along with our three workout partners, did not set out to pioneer organized weight training at Dartmouth. We were just doing what we thought would improve our strength, health and well-being—and enjoying it together. Unwittingly, we were setting the pattern for like-minded students and athletes as well as the College for generations to come. Ironically, we lifted weights in a corner of what is now the Berry Fitness Center.

"We lifted almost daily, suffering looks of disdain from the coaches and gym instructors."

JOEL LASKYpumps iron in Dallas, Texas,while DAN ANZEL works out in LosAngeles and DON KENNEDY rows miles inPhoenix, Arizona.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

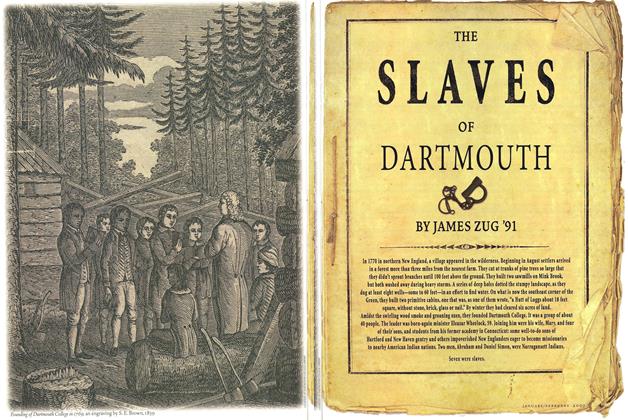

Cover StoryThe Slaves of Dartmouth

January | February 2007 By JAMES ZUG ’91 -

Feature

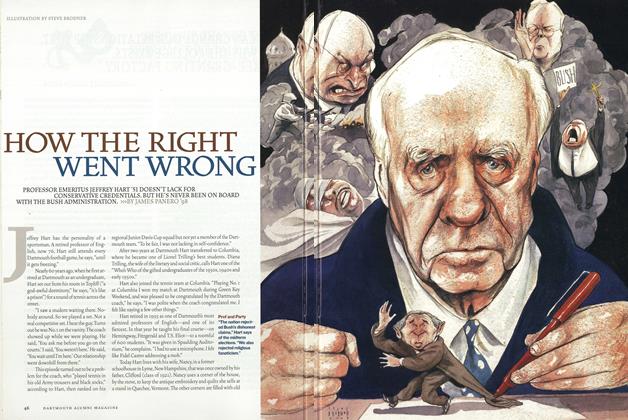

FeatureHow the Right Went Wrong

January | February 2007 By JAMES PANERO ’98 -

Feature

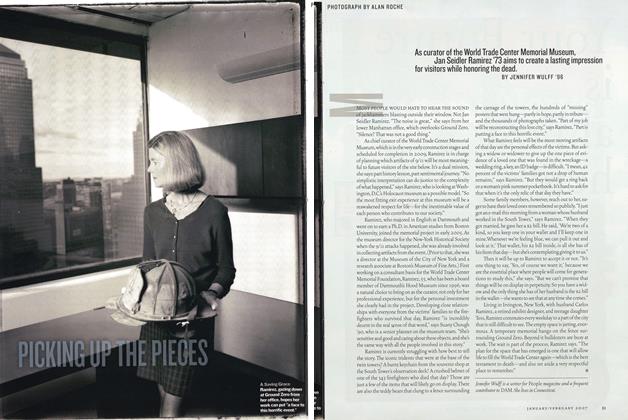

FeaturePicking Up the Pieces

January | February 2007 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

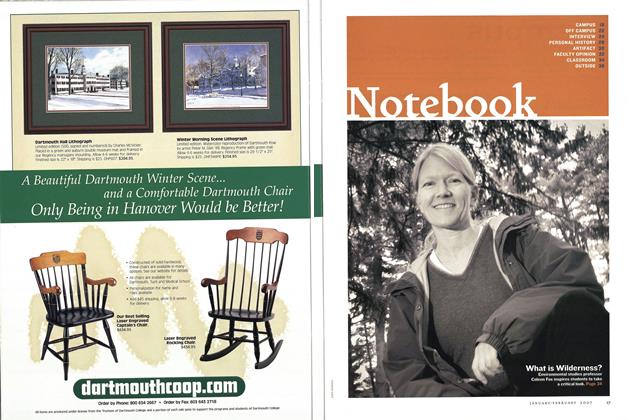

FeatureNotebook

January | February 2007 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

January | February 2007 By William Landmesser '74 -

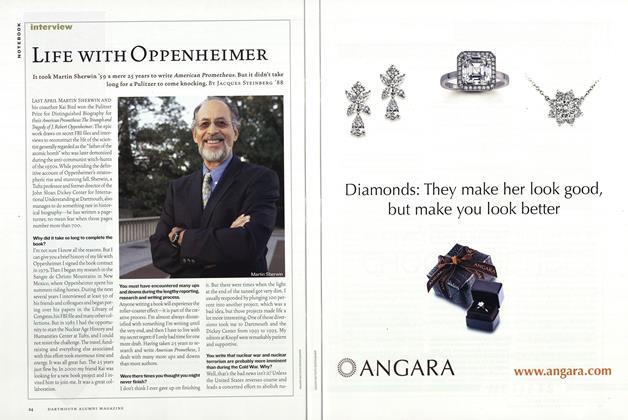

Interview

InterviewLife with Oppenheimer

January | February 2007 By Jacques Steinberg '88

PERSONAL HISTORY

-

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYClose to Home

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2022 By APOORVA DIXIT '17 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYHigh Fidelity

Sept/Oct 2006 By Brian Corcoran ’88 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYOut Of The Woods

Nov/Dec 2000 By J. Mark Riddell ’90 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

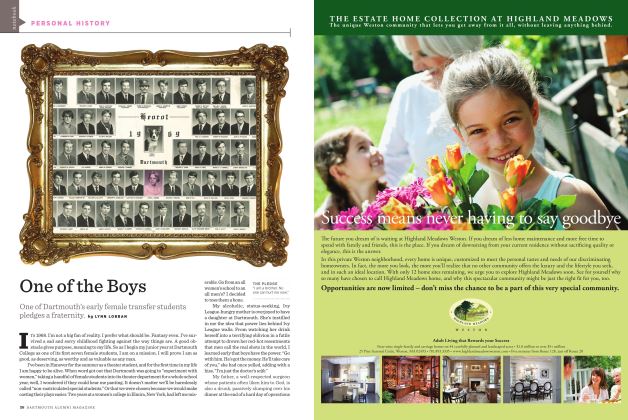

PERSONAL HISTORYOne of the Boys

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 By LYNN LOBBAN -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYChasing Pollock

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2025 By SAM SEYMOUR '79 -

PERSONAL HISTORY

PERSONAL HISTORYLearning Experience

July/August 2008 By Susan Marine