Chasing Pictures

An adventurous photojournalist goes to extraordinary heights to shoot extraordinary photographs.

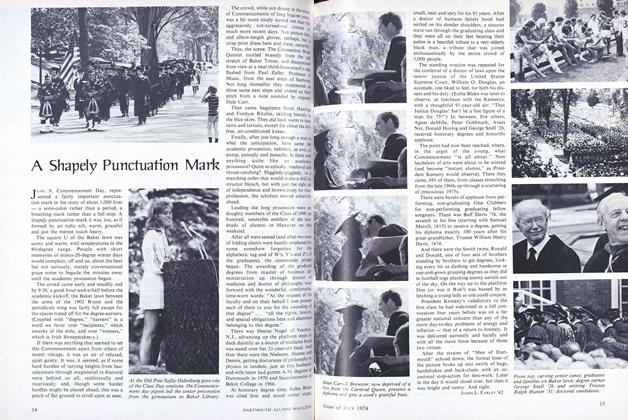

Jan/Feb 2002 PETER McBRIDE ’93An adventurous photojournalist goes to extraordinary heights to shoot extraordinary photographs.

Jan/Feb 2002 PETER McBRIDE ’93AM ADVENTUROUS PHOTOJOURNALIST EXPLAINS WHY HE GOES TO EXTRAORDINARY HEIGHTSTO SHOOT EXTRAORDINARY PHOTOGRAPHS,

I hang my torso into the desert air above Cairo .Just feet in front of a whirling 11-foot propeller, I strain to maintain my balance on the edge of the biplanes open cockpit, hoping to freeze the moment on film: an aviation "time machine" set against a backdrop of the Pyramids of Giza.

At roughly 500 feet, we are circling the archaeological wonders of time in the largest airworthy biplane in the world—a Vickers Vimy. To the west, the Sahara stretches to the horizon. To the east, Cairo's streets, notorious for "too many wheels," quiver with life. The two pilots behind my gunner's seat know I am stretching my limits, but neither breaks radio silence. We all know it is a fleeting moment. With a tenuous authorization by a fickle Egyptian military, there will be no second chances.

There is a camera mounted on the wingtip and triggered through the plane's wiring system. If it malfunctions, we have the shots I capture while hanging out of the front cockpit.

It has been some 80 years since a World War I Vickers Vimy orbited these pyramids. In 1920 a Vimy named the Silver Queen flew over the famed tombs before its two South African pilots lumbered the aircraft south, becoming the first men ever to reach Cape Town from London by air—in 43 days. Now we attempt a modern re-enactment adventure. The hope is that it will not only highlight a major historical aviation achievement, but offer a comparative aerial look at a rapidly changing African continent. Of course, that depends much in part on whether I do my job properly.

I work as a photojournalism I document life and our surroundings: its beauties, tragedies and comical intricacies. In many ways it is a ridiculous job: overly competitive, over-romanticized, lonely and unpredictable, and its impact is difficult to measure.

But at its best, photojournalism doesn't just refresh dusty memories. It reminds us of the diversity, wonders and struggles of life itself. Photography opens doors into worlds that we often don't know, that we wish we could know or that we wish never existed. Like many photographers, I try to use the camera to focus on issues I am most passionate about—land and wildlife conservation, human rights and even Latin rumba bands—in the hope that imagery can educate or inspire thought and even change things. On occasion it does, even in todays numbing, media-filled world.

Over the years, however, adventures have become one of my main calling cards. Magazine editors often initiate an assignment by asking me questions such as "What do you think about climbing?" or "How about hanging 0ff...?" or "Do you think you can handle riding a camel for 1,500 miles?"

Whether it is a love of the outdoors or a relentless wanderlust, or maybe that my joints have yet to protest, I regularly find myself accepting before I realize the true extent of the task.

In the one-uppance world of today s adventure culture though, I have witnessed an element of selfindulgence that can stretch beyond absurd. My reaction is to try to document adventures in which the expedition serves to highlight something more important—a region, culture, historical moment or changing environmental situation. Such adventureswhether on a yak train with snake jerky and voodoo potions or a stroll into an unknown corner of one's own town—force us to notice not only our personal limitations, physical and mental, but also our surrounding which too often go unnoted.

I have opened such windows into our world through journeys to more than 30 countries in the past five years. In that time I've often been asked, "What's your typical day like?" The short answer: Odd. And as the following notes about some of my assignments demonstrate, there's no such thing as a typical day.

It is 3 a.m. and I'm fumbling around camp, in the dark, looking for my camera. We are on rock shelf at 20,000 feet, below the Polish Glacier on Argentina's Aconcagua, one of the world's highest peaks.

I have a splitting headache from the altitude and my body shakes with cold. I covet my sleeping bag but I hope to find and turn off my camera, which is sheltered under some rocks as protection against frequent 75-m.p.h. blasts of wind, without using a light (it would destroy the picture).

I have spent three nights fighting the early morning chill and blasting winds trying to capture the clarity of the Southern Hemisphere's night sky. By leaving the camera lens open for roughly six hours, the film picks up star light as the earth performs its nightly rotation, leaving star trails behind. The process involves mid-slumber recapades such as this, which leave me cursing the job—and mountaineering. I sometimes hold a bitter taste for the sport, particularly when I think of the many friends taken by it.

Yet mountains can be addicting. Watching stars from the roof of the Andes or seeing a purple sunrise above tree line after hiking through the night etches memories that refuse to dim.

Having grown up in Colorado, I am a mountain addict, but I do not pretend to be an expert. So when I am asked to take on climbing assignments, I am always torn between my addiction and my fear of the danger, which is heightened by the added weight and awkwardness of camera gear.

But I can't resist those high-altitude star vistas or purple sunrise moments. I push aside the cold morning pains, lug the weight and hope to stay within safety's camp.

I am not afraid of heights, but today my altitude is a pressing concern. When I ask the head rigger if he ever thinks about falling, he responds almost with a shrug. "I just figure that if I do, my chip is up and I had a good life," he says.

Surprisingly, such direct thinking helps. From an overhanging granite wall we are dangling from ropes nearly 3,000 feet above the Yosemite Valley floor. Yosemite Falls roars and tumbles in sheeting waves down the face only 50 feet to my left.

I am shootingthe dance company Bandaloop, which combines climbing and dance to form a weightless performance—an art that treats air as a stage. For five days we rappel down some 300 feet on individual lines. A TV crew and I attempt to capture the beauty of these dancers as they float effortlessly in perfect unison.

As long as I focus on the photography, my nerves don't bother me. Despite double and triple checks on every buckle, every strap, thoughts of simple mistakes—attaching an ascender device backwards, not locking a carabiner, freeing a loose rock, dropping a lens—swirl through my head. Having never even been on a big wall before, I am in new territory using mostly borrowed climbing equipment. Double, triple check.

I unstrap a camera from my back and change lenses. Then I hear it, but too late: My lens cap catches a harness strap and flips off. I turn only to watch the cap flutter into space. Out of curiosity, I count the free fall. Twelve seconds before I lose sight of it roughly two thirds of the way down. Stop thinking and just focus on the images, I tell myself. For seven hours I hang in my harness as the dancers practice, perform, rest and repeat everything.

On the way out a dancer's rope kicks off a loose scab of granite. I am ascending my line below him when the rock catches my upper knee. I cover my head fearing more will follow. low. Nothing. A chunk of skin is gone from my knee, but the incident is minor—just a small bleeder. I continue on, grateful that my chip isn't up.

I leave Ruben's family today and drive the rental rig north, pondering how his family forced me to be more messenger than journalist. Without phones in the tiny

Mexican community of Ojo Azules, it took me three days of exploring dead-end dirt roads to find Ruben's wife and son. In a barren home with a snow-screened TV flickering in the corner, his wife continuously interviewed me in Spanish: "When is Ruben returning? How is he? Will you tell him we love him?"

I was not ready for this. I had come to see her life and ask her questions about her modern Mexican lifestyle—in which husbands like hers chase dollars "Up North" most of the year. But obviously her questions answered mine.

Now I am some 200 miles south of the U.S. border, searching for the Olave family. One brother comes every year to Colorado illegally. If the timing is right, the family has agreed by phone to let me shadow his border crossing. I wonder if I can handle the risk.

At 10 p.m. I stop along a dirt road, too tired to continue. I decide to sleep in the bushes, thinking a night in the desert will be an appropriate warmup for the border run. Within minutes I curse the desert sky. Something is attacking mewrist, neck, ankle! I hobble back to the car, still cursing. I hit the lights and see a culprit. A small scorpion lodged under my watch band twitches, its tail stuck in my wrist.

Petrified, I get back behind the wheel and race off. Forty minutes later, unsure if my racing heart is due to driving too fast or scorpion poison, I see a truck stop. A weathered truck driver assures me that scorpion stings are painful but harmless. "Hombres crossing the border get stung all the time," he casually explains. "Don't worry, my friend, you will live."

trust like many children, 10-year-old Cesar Lujano catches a ride to school eachmorning. But unlike most kids, Cesar'stransport is something out of a HarryPotter story—he rides a dragon boat.At 13,000 feet on the western sideof Lake Titicaca, Peru, the Lujanos liveon floating islands made of reeds. Foryears the Los Uros community has chosen its floating island lifestyle over theshore, as it provides them better accessto fishing, avoids taxes and, today,brings in tourist dollars.

I wake up at 4 a.m. two days in a row to take the water taxi to Cesar's home. Arriving at sunrise both days not only builds trust with the Lujano family, it allows me a ride on the dragon boat with him and his grandmother.

Earning trust among foreign cultures is as challenging as any expedition. But trust is paramount, whether hitching rides on the dragon boats of the world or photographing friends. My photo assignments—in which editors press for intimate moments in

foreign places under deadline—rarely allow time to build such bonds. Acting invisible sometimes works, but asking questions and being unafraid to make a fool of myself is often far more successful.

In a market in Pisac, Peru, I mimic animal sounds (with a Spanish accent, of course) to gain a child's attention. At first the market stops in shock. Then the vendors join me, adding condor and llama sounds to the repertoire.

Trading Places McBride with a Masai warrior in the hills north of Mt. Kilimanjaro. "One warrior offered me his spear, I handed him my camera," says the photographer. "He taught me how to throw, and I directed him through the camera's buttons. I lobbed some lame arcs, he fired off some shots." McBride usually avoids such material exchanges, not only to protect his equipment but to protect the integrity of such cultures that struggle to maintain their heritage. But on occasion, he says, "trading roles helps dilute the sensation that the photographer is only taking and the subject only giving."

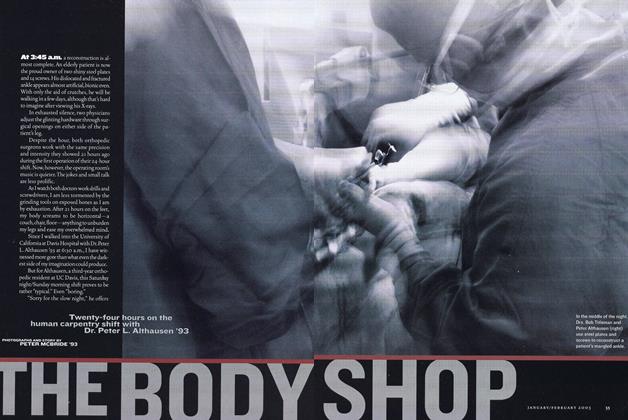

Aerial Orchestra McBride took this shot of the Vickers Vimy over Victoria Falls in Zimbabwe while stapped to the strut of a helicopter. A Vimy Bored the first hole in the sky above these falls in 1920, and one of its polots, Chistopher Quintin-Brand, snapped the first woder. "Like the viewers of those first images, I was shocked when I saw mu own film," says McBride. "Due to stress and commotion involved in air-to-air photogrphy, I barely had time to enjoy or even note the awesome power of the falls untill sat down to edit my film in a quiet room four weeks later."

Chasing Pictures

Eye on the Sky The aerial dance company Bandaloop performs at Yosemite (shot for Smithsonian in 2000); star trails illuminate a camp (bottom left) on Aconcagua in the Andes (shot for Argentine magazine Lugares in 1997); climbers ascending Mt. Rainier at sunrise (left) include Susan Luria '89 at right (shot for Outside in 2000).

Chasing Pictures

A Stranger in Strange Lands A reed boat serves as a schoolbus (above) on Peru's Lake Titicaca (shot for a British travel agency in 2001); a Peruvian woman with child (left) at a market in Pisac (also shot for the travel agency); an immigrant heads north (top left) from Chihuahua, Mexico (shot in 1997).

"I use the camera in the hope . that imagery can educate or inspire.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureWorkouts From Hell

January | February 2002 By BRAD PARKS ’96 -

Feature

FeatureThe New New York

January | February 2002 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

FeatureInnocence Lost

January | February 2002 By DOUGLAS RAYBECK '64 -

Feature

FeatureA Mother's Dilemma

January | February 2002 By JAMIE HELLER '89 -

Feature

FeatureA Murmur of Normalcy

January | February 2002 By NELSON BRYANT '46 -

Feature

FeatureThe New Normal

January | February 2002