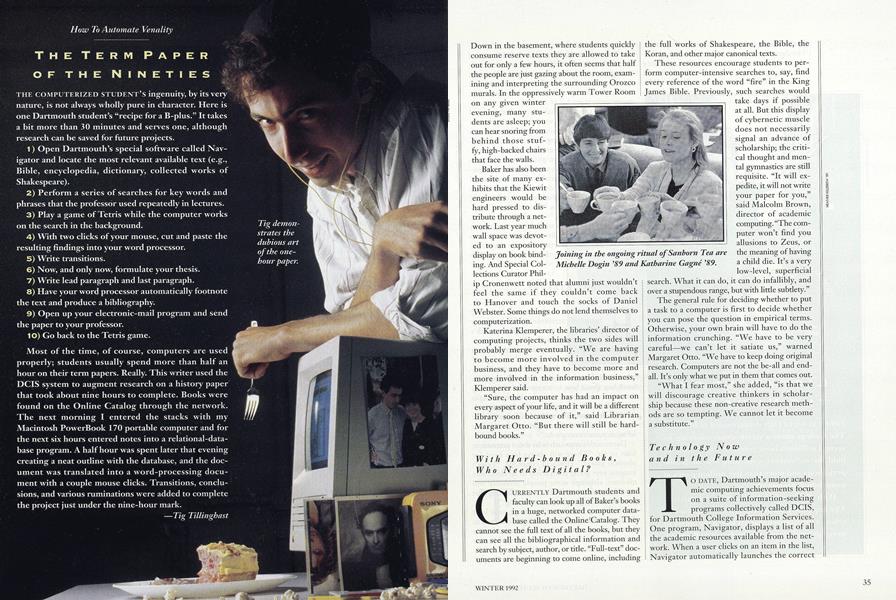

CURRENTLY Dartmouth students and faculty can lookup all of Baker's books in a huge, networked computer database called the Online Catalog. They cannot see the full text of all the books, but they can see all the bibliographical information and search by subject, author, or title. "Full-text" documents are beginning to come online, including the full works of Shakespeare, the Bible, the Koran, and other major canonical texts.

These resources encourage students to perform computer-intensive searches to, say, find every reference of the word "fire" in the King James Bible. Previously, such searches would take days if possible at all. But this display of cybernetic muscle does not necessarily signal an advance of scholarship; the critical thought and mental gymnastics are still requisite. "It will expedite, it will not write your paper for you," said Malcolm Brown, director of academic computing. "The computer won't find you allusions to Zeus, or die meaning of having a child die. It's a very low-level, superficial search. What it can do, it can do infallibly, and over a stupendous range, but with little subtlety."

The general rule for deciding whether to put a task to a computer is first to decide whether you can pose the question in empirical terms. Otherwise, your own brain will have to do the information crunching. "We have to be very careful—we can't let it satiate us," warned Margaret Otto. "We have to keep doing original research. Computers are not the be-all and end-all. It's only what we put in them that comes out.

"What I fear most," she added, "is that we will discourage creative thinkers in scholarship because these non-creative research methods are so tempting. We cannot let it become a substitute."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureKnow Your Place

December 1992 By George J.Demko -

Feature

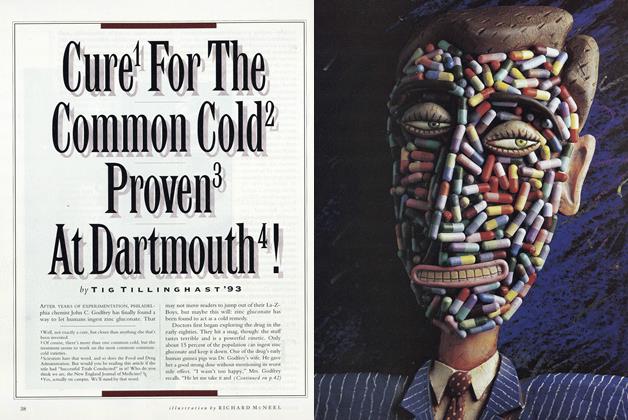

FeatureCure1 For The Common Cold2 Proven3 At Dartmouth4!

December 1992 By TIG TILLINGHAST '93 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Library Culture

December 1992 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Ether Library

December 1992 -

Cover Story

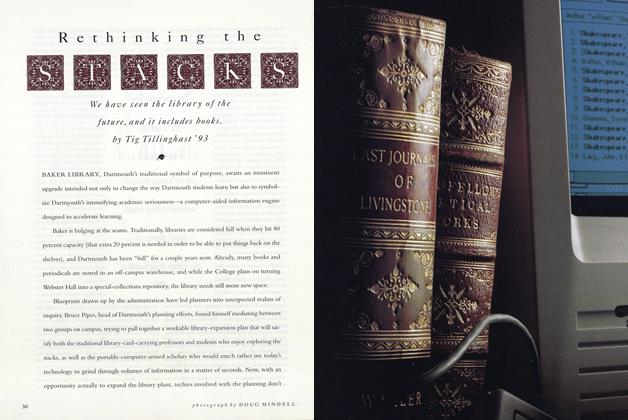

Cover StoryRethinking The Stacks

December 1992 By Tig Tillinghast '93 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTechnology Now and in the Future

December 1992

Features

-

Feature

FeaturePro Bono Publico

JANUARY 1973 -

Features

FeaturesCenter of Attention

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2022 By ABIGAIL JONES '03 -

Feature

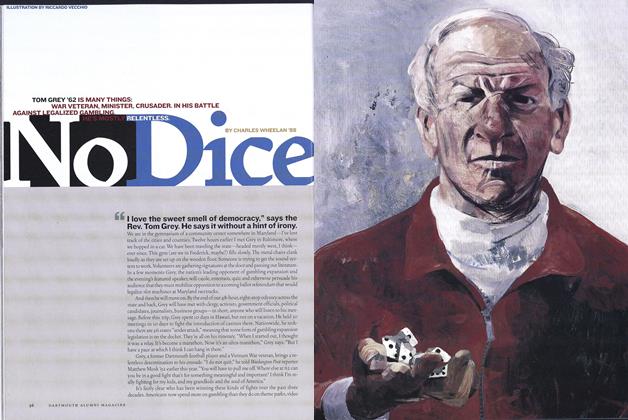

FeatureNo Dice

July/Aug 2003 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

September | October 2013 By DARTMOUTH COLLEGE -

Feature

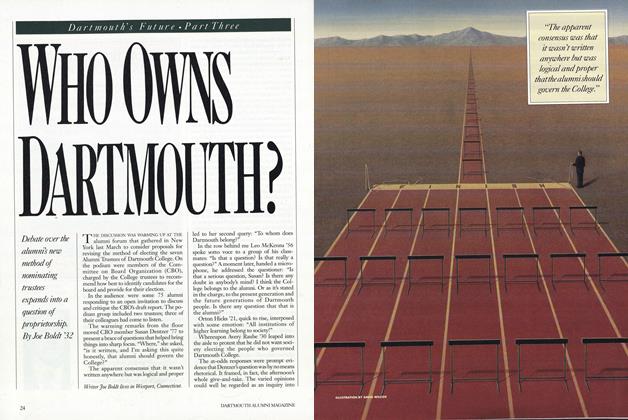

FeatureWHO OWNS DARTMOUTH?

FEBRUARY 1991 By Joe Boldt '32 -

Feature

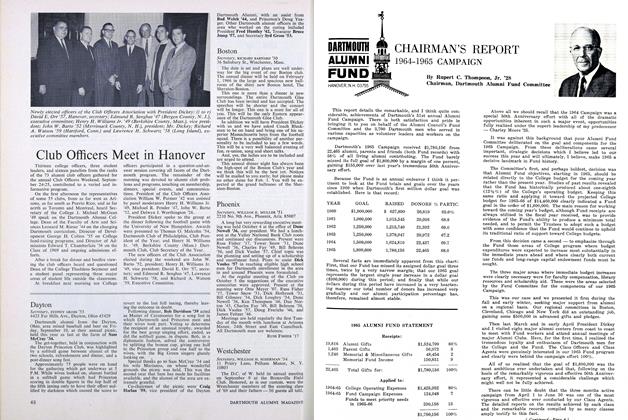

FeatureCHAIRMAN'S REPORT 1964-1965 CAMPAIGN

NOVEMBER 1965 By Rupert C. Thompson, Jr. '28