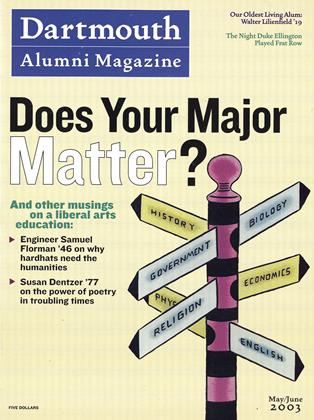

Does Your Major Matter?

Career-obsessed freshment certainly think so. But alumni know better: A liberal arts education is useful no matter what line of work you choose.

May/June 2003 Lisa FurlongCareer-obsessed freshment certainly think so. But alumni know better: A liberal arts education is useful no matter what line of work you choose.

May/June 2003 Lisa FurlongCAREER-OBSESSED FRESHMENT CERTAINLY THINK SO.BUT ALUMNI KNOW BETTER: A LIBERAL ARTS EDUCATIONIS USEFUL NO MATTER WHAT LINE OF WORK YOU CHOOSE.

When April Stempien-Otero '86 entered Dartmouth in the fall of 1982 she expected to major in biology. She already knew she wanted to be a doctor. After reviewing her curriculum options, however, she determined there weren't all that many biology or biochemistry courses that interested her. She resolved instead to switch her concentration to English.

Around her, other would-be doctors were majoring in sciences but she remained undeterred. "I had grown up with a concept of liberal arts education," she says now. "I figured as long as I had my pre-med requirements covered, I'd be fine. I'd always loved English literature and made my decision based on two things: wanting to write better and literature's ability to help you understand the human condition.

"It wasn't until I started interviewing for medical school that my major was called into question," she says. "Everyone wanted to grill me on why I hadn't majored in biology."

But the lack of a biology major did not keep her from attending medical school at the University of Connecticut and becoming an assistant professor in the University of Washington's division of cardiology, where she's involved in both patient care and cardiovascular research. In fact, according to Stempien-Otero, her grounding in English enabled her to overcome a phobia that paralyzes many in her field: fear of sitting down and having to write a long grant proposal or paper.

Just as importantly, her college focus on modern writers has helped her "get inside the head of the common man," she says. "When I did my residency in Charlottesville, Virginia, I had a ton of patients who could have walked right out of a Faulkner novel."

Stempien-Otero's concept of a liberal arts education would no doubt please Dartmouth President Emeritus James O. Freedman, who has touted a broad-based academic foun- dation as "the surest instrument yet devised for civilizing qualities of mind and character that enable men and women to lead satisfying lives and to make significant contributions to society."

But despite the many Dartmouth alums whose work and personal lives exemplify this credo, incoming freshmen continue to arrive in Hanover thinking that their choice of a majorwill determine their job prospects upon graduation and that a "wrong" choice will limit them not just when it comes to graduate school but also in corporate America.

Emanuel "Skip" Sturman '70, director of Dartmouth's Career Services Center, says he constantly reminds students that employers look for attributes other than expertise in a specific field. "Companies don't expect a student to walk through the door with a complete knowledge of what the company does or how," says Sturman. "But they are looking for evidence of the skill sets that are needed in their companies. This evidence can come not only from course work but from working at the radio station or the newspaper. It frequently comes from a leadership position in a social organization, from minors, from volunteer experience."

The same message comes from on-campus recruiters.

Debbie Vinokur, senior partner and director of human resources for Ogilvy & Mather in Boston, says that she looks not only for a basic understanding of advertising, but also creativity and different ways of thinking. "We want to see students who are passionate about some discipline. We purposely don't look for marketing majors. The varied interests represented by a liberal arts education make Dartmouth students ideal candidates for jobs in marketing communications."

Says Matt Stone, director of North American recruiting for Mercer Consulting in Boston: "Your major doesn't matter. When we come to Dartmouth we're impressed by how well-rounded the students are. I look for business experience an entrepreneurial campus club, controlling the budget of a campus organization."

Consider Stu Zuckerman 70 and Jon Douglas 92, both of whom gained valuable pre-professional experience outside the classroom. Active with WDCR and still a member of the board of overseers of Dartmouth Broadcasting, Zuckerman says he arrived at Dartmouth "feeling it was important to go to a liberal arts college despite my yearnings to study journalism. He purposely didn't apply to schools that offered that or communications majors. After working at the radio station as a disc jockey and selling airtime and producing commercials, he decided to experiment with a special summer program at Stanford's Broadcasting and Film Institute. "I wanted to see if focusing on my field of interest would be a better course of study," he says. I found I missed Dartmouth's liberal arts approach and decided I could study communications in graduate school."

Zuckerman returned to Dartmouth and majored in psychology simply because it captivated his interest. Today, as vice president of sales and marketing for PBS Nightly Business Report in New York, he says his major has prpbably helped him most when he's had to motivate employees. He's surprised to be working on the business side of television rather than on the air, but he headed in that direction at WDCR. "The students were expected to get the needed support for the station and I found I enjoyed dealing with the Hanover merchants," he says.

Douglas also entered Dartmouth with an interest honed in high school: music. He stayed with it (after ditching a dual major in chemistry in part because it interfered with winter band) but spent much of his college career working for this magazine, where he de veloped his editorial skills. After a series of editorial positions, he's now the travel editor for Smarter Living.com in Boston.

Says senior associate dean of students Dan Nelson '75: "It's wonderful to see someone pursue a given interest or just serendipitously discover a field of study and find a sense of connection that sparks interest. Many students will change their majors two, four or even seven times."

Nelson, who majored in religion and English, says there's no need to connect a major to a potential career. "But the class deans still spend a good deal of time disabusing students of the notion it's so," he adds.

Roughly two-thirds of incoming freshmen arrive at Dartmouth with a major in mind, says dean of first-year students Gail Zimmerman. "They range from those who have a passion to those who have a career goal. That goal may be rooted in security, prestige or scholarship pressure," says Zimmerman.

Many students—citing pressure from those footing their tuiton bills (a.k.a. their parents)—feel compelled to major in something "practical," a compunction that is especially strong among foreign students, she says.

"Most kids who are good in science in high school are perceived as the smart kids," says Zimmerman, explaining why roughly 45 percent of entering freshmen identify an interest in a science. Often comes a day when one of these smart kids realizes he or she doesn't really like science or isn't as good at it as previously thought.

"Then comes the huge decision: 'What do Ido now?' says Zimmerman. One of the books she recommends to such students is DoWhat You Love and The Money Will Follow: Discovering Your Right Livelihood by Marsha Sinetar.

"Dartmouth students are ambitious, motivated and have wonderful ideas," Zimmerman says. "The challenge is helping them focus and helping them relax."

Sometimes a student abandons an early interest as a major only to return to it after graduation. One case in point is that of Scott Marr '88, who came to Dartmouth inclined toward a pre-med curriculum but who switched to economics after being disillusioned by a summer job. "I had thought about being a vet, but one summer in a veterinary hospital changed my mind," he explains. Marr chose economics because he was good in math.

He completed an internship and residency in finance—at First Boston in New York and State Street Capitol in Boston—but found himself yearning once again for a career in medicine. After completing undergraduate pre-med requirements at Harvard's Extension School and doing research for a year at Massachusetts General, Marr was accepted by UMass Medical Center in Worcester. His work experience, not his major, was "the key thing people wanted to talk about when I was interviewing," he says of his application process. "People were impressed I was able to make the change. I can definitely say your major doesn't matter."

Now a member of the faculty at Maine Medical Center in Portland and a sports medicine practitioner with Casco Bay Family Physicians in Falmouth, where he lives, Marr says his economics grounding still comes in handy.

"I notice how poor doctors' financial knowledge is," he says. "My partners tend to defer to me in that area." Given todays health-care climate, financial expertise has other benefits, too: "It always comes down to the almighty dollar, Marrsays. Its important to be able to prove your worth."

Marr's experience is yet another reminder that a major shouldn't determine your career any more than a career goal should determine your major. No less an authority than former U.S. labor secretary Robert Reich '6B, now a professor at Brandeis, says he cautions students about choosing a major. "Don't pick one with a future career path in mind," he says, "unless you're so passionate about a subject that you're sure you want to spend your life pursuing it. Even then, beware. You might discover even stronger intellectual passions where you least expect them." (Although College records indicate Reich was a government major, he has no recollection of declaring any major and remembers taking only three government courses.)

Even those who succeed in careers planned early can get mere via unexpected majors that expand rather than narrow ones focus as playwright Heather McCutchen '87 of Durham, Connecticut, can testify.

"I wanted to be a writer since I was 8 years old, and I knew when I decided on a liberal arts college that any major would be useful," says McCutchen. "I took a freshman seminar in religious autobiography with professor Kevin Reinhart, and it was clear to me then that's what I wanted to study. Religion is so much about what motivates people, it has so much to say about their lives, their priori ties, their aspirations—things I wanted to write about."

McCutchen found her religion major more helpful to her than English, the predictable choice. Last fall she published her first children's book, Lightland. Does it have religious overtones? "Doesn't everything?" she says.

She does remember, however, having to justify her choice of major to unexpected inquisitors. "Every year when I went to the bank to fill out my student-loan forms, they d ask me, Now what kind of jobs do religion majors get?' I told them a lot of religion majors go to law school," she says.

As Reich contends: 'An important aspect of an undergraduate education is learning how to learn—how to launch your own lifetime of learning. This could be discovered in a major but doesn't depend on a major."

And as David Sobie '94, an English major now enrolled at Tuck, observes, "Majors matter to the extent they make Dartmouth graduates the intelligent, interesting people they are."

Some Famous AlumniAuthor Theodor "Dr. Seuss" Geisel '25 English Dartmouth President John Sloan Dickey '29 HistoryGovernor Nelson Rockefeller '3O Senior FellowDr. C. Everett Koop '37. Zoology IBM CEO Lou Gerstner '63 Engineering SciencesSenator Paul Tsongas '62 ...Classics Author Louise Erdrich '76............. Creative Writing GE CEO Jeffrey Immelt '77. Mathematics and EconomicsAstronaut James Newman '78 PhysicssPolitical commentator Laura Ingraham '85 English NFL quarterback Jay Fiedler '94 Engineering

Don't pick a major with a future career path unless you're so passionate about a subject that you're sure spend your life pursuing it. Even then, beware." —Robert Reich '68 in mind you want to

LISA FURLONG is a freelance writer who contributes regularly to Dartmouth Alumni Magazine. She lives in Center Harbor, New Hampshire.She majored in American studies—at Wellesley.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Affirming Flame

May | June 2003 By SUSAN DENTZER ’77 -

Feature

FeatureWhy an Engineer Needs English Lit

May | June 2003 By SAMUEL C. FLORMAN ’46, TH’46 -

Artifact

ArtifactPhil’s Favorites

May | June 2003 By Phil Cronenwett -

Personal History

Personal HistoryReminiscing In Tempo

May | June 2003 By Cliff Ennico ’75 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Global Classroom

May | June 2003 By Jack Shepherd -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

May | June 2003 By MIKE MAHQNEY '92

Lisa Furlong

-

Interview

Interview“A Time of Living”

Nov/Dec 2004 By Lisa Furlong -

INTERVIEW

INTERVIEW“Fat Don’t Fly”

Jan/Feb 2010 By LISA FURLONG -

Continuing Education

Continuing EducationF. William McNabb ’79

May/June 2010 By Lisa Furlong -

Continuing Ed

Continuing EdKaren (Jennings) Lewis ’74

May/June 2011 By Lisa Furlong -

CONTINUING ED

CONTINUING EDDana (Thomas) Bevan ’69

MAY | JUNE 2017 By LISA FURLONG -

CONTINUING ED

CONTINUING EDCal Newport ’04

JULY | AUGUST 2021 By LISA FURLONG

Features

-

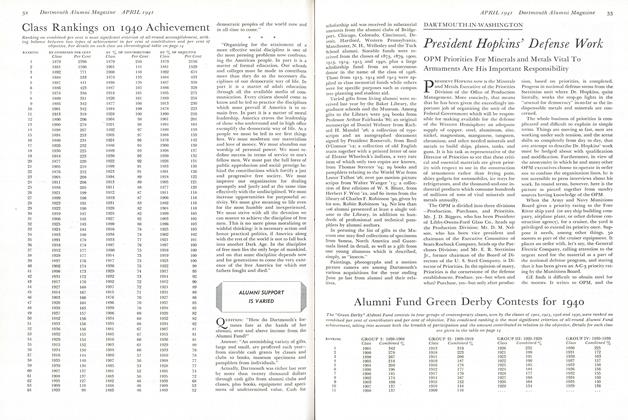

Feature

FeatureClass Rankings on 1940 Achievement

April 1941 -

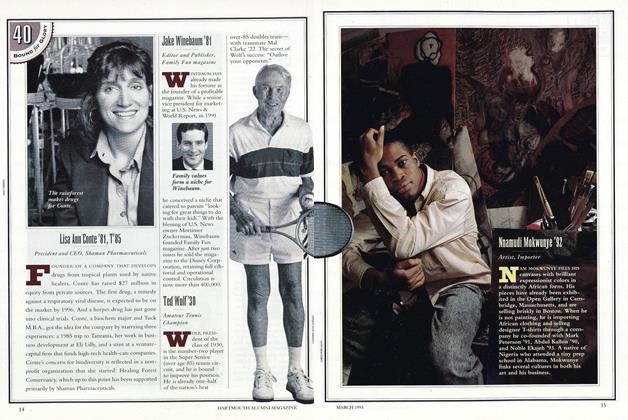

Cover Story

Cover StoryTed Wolf '30

March 1993 -

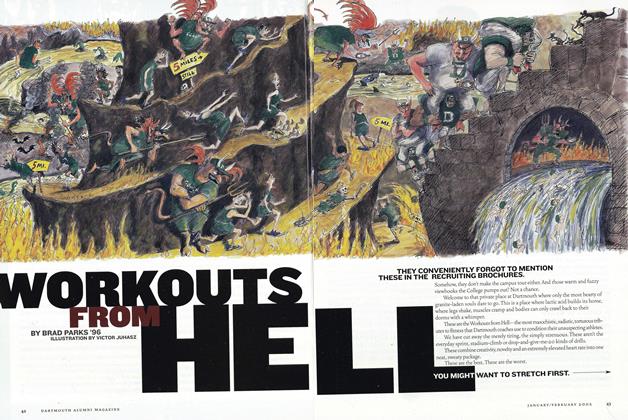

Feature

FeatureWorkouts From Hell

Jan/Feb 2002 By BRAD PARKS ’96 -

Feature

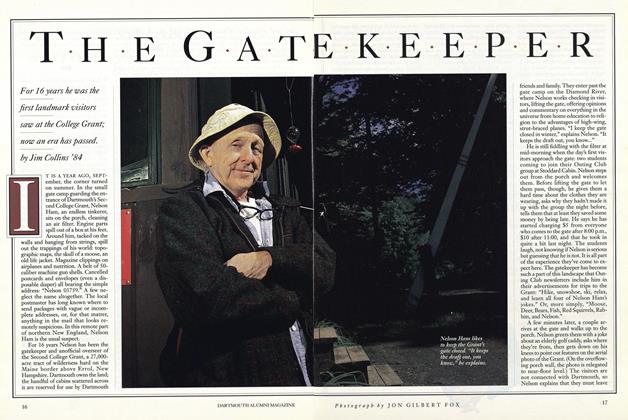

FeatureThe Gate keeper

SEPTEMBER 1991 By Jim Collins '84 -

Feature

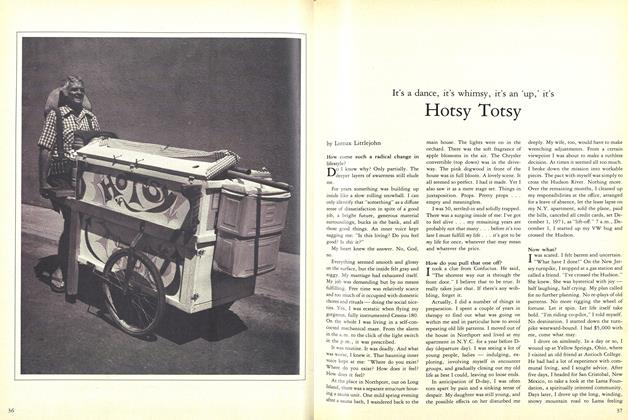

FeatureHotsy Totsy

APRIL 1982 By Lomax Littlejohn -

Feature

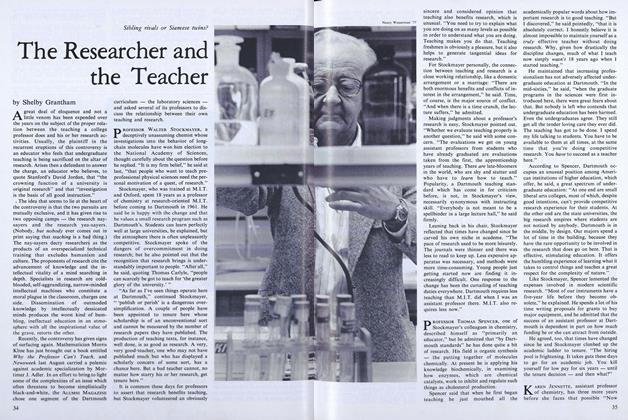

FeatureThe Researcher and the Teacher

November 1978 By Shelby Grantham