The Affirming Flame

In uncertain times, a liberal arts education speaks to us—if we have the stillness and courage to listen.

May/June 2003 SUSAN DENTZER ’77In uncertain times, a liberal arts education speaks to us—if we have the stillness and courage to listen.

May/June 2003 SUSAN DENTZER ’77AT DARTMOUTH'S CONVOCATION LAST SEPTEMBER, President James Wright spoke eloquently of the 11 members of the Dartmouth family who were lost exactly a year earlier in the attacks of September 11. Among those whose names he invoked was one of my classmates, Joseph Flounders '77, a money-markets broker who died at the World Trade Center. Wright noted that Joe perished after he had "turned back to help a colleague" as thousands were escaping from the trade centers south tower. A few months after Joe's death, his wife, Patricia, committed suicide—"one more victim of the attacks," as Wright observed.

These losses are incalculable, as are those of the nearly 3,000 others who died in New York, at the Pentagon in Virginia and in the downing of United Airlines Flight 93 in Pennsylvania. Along with our grief, many of us sense that our lives and perspectives have been altered dramatically by 9/11. But little did I realize at the time how much the events of that day would also produce a kind of homecoming—for they would carry me, inevitably, back to Dartmouth.

Like most Americans, I witnessed the horror in New York first on the television screen. Then, as I drove to my Arlington, Virginia, office, located just over a mile from the Pentagon, I saw the smoke rise from that attack site. As a television correspondent covering health-care news, I quickly headed for the Virginia hospital where many of the Pentagons injured were taken for treatment. I spent the rest of the day following that story, while also making frantic cell-phone calls to contacts in the New York health-care community for news about the situation there.

In the dark weeks that followed, I continued to be immersed both personally and professionally in the tragedy. I mourned the husband of a dear friend who died at the World Trade Center. I struggled to keep my professional composure as I worked on stories about recovery and identification of remains, and profiled the psychological and physical trauma suffered by survivors in New York and Washington. Retaining any sense of emotional distance from these stories was, of course, impossible.

As was no doubt true for many, I felt an intense need to assemble the pieces of the experience into some organized whole. I also needed an outlet for the expression of the ongoing sense of horror and grief. At some point in those early weeks, my mind wandered back to a set of observations made by Dartmouth's 15th president, James O. Freedman, who served the College from 1987 to 1998.

President Freedman is a cancer survivor who must contend to this day with periodic rounds of chemotherapy to battle his disease, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. He once wrote powerfully of what he termed his lonely hours of introspection after the shock of first learning of his diagnosis in 1994, in the midst of his Dartmouth presidency. As he pondered his mortality, he wrote a column for this magazine in which he said he was struck by:

two realizations—first, that life is a learning process for which there is no wholly adequate preparation; second, that although liberal education isn't perfect, it is the best preparation there is for life and its exigencies. It does enable us better to make sense of the events that either break over us, like a wave, or quietly envelop us before we know it, like a drifting fog.

During the difficult and dismaying days of the last two months, liberal education has helped me in that most human of desires—the yearning to make order and sense out of my experience.

President Freedman wrote that he thought at length about literary modes—romantic, tragic, comic, satiricand how these narrative categories exist because, "as the Greeks and others have understood for millennia, life tends to play itself out in ways that seem romantic, tragic, comic or satiric—or perhaps all four." He continued:

What, then, is the use of a liberal education? When the ground seems to shake and shift beneath us, liberal education provides perspective, enabling us to see life steadily and see it whole. It has taken an illness to remind me, in my middle age, of that lesson. But that is just another way of saying that life, like liberal education, continues to speak to us—if we have the stillness and the courage to listen.

There it was—the truth—so blindingly obvious, and yet so profound. It was time to fall back on my liberal arts education, and in particular, on much of what I had first been exposed to at Dartmouth.

I turned to poetry.

FOR ALL THE SHARP AND MISTY MORNINGS, I HAVE few memories of college that are as'vivid as those involving poetry. I recall discovering John Donne in an English course with professor Richard Corum; hearing the inimitable pro- fessor Bill Cook read aloud the work of Langston Hughes; listening to Seamus Heaney, visiting from Harvard, or Adrienne Rich, up from New York, giving readings of their own works in the Sanborn House library. Amid career, marriage and three children, there hadn't been much time for poetry in the intervening years. Now there had to be.

I settled quickly on an old favorite, Robert Frosts "Directive." The poems first line—"Back out of all this now too much for us"—had been running through my mind for several weeks since the attacks. I had first read "Directive" in an American poetry course with Professor Cook, and had later written a paper on it during a Robert Frost seminar with professor Ned Perrin. Studying Frost under both Cook and Perrin had effectively shattered any notion that the poet was the banal pastoral spokesman for autumn-leafy New England. I remembered his poetry instead as the poetry of many dark, deep and lovely places; troubled places set apart. And that first line of "Directive" captured all too acutely how I was feeling in the aftermath of 9/11.

Another poet, Archibald MacLeish, once wrote, "A poem must not mean, but be." "Directive" always seemed to me to demonstrate the truth of that dictum. Although I have read this poem hundreds of times in my life, to this day I don't know what it means; I only know what it is. It's a tale told by an unnamed narrator, drawing us back out of all this to a distant place that time has forgotten: "There is a house that is no more a house/Upon a farm that is no more a farm/And in a town that is no more a town." I wanted to escape to that place, by steeping myself in the extraordinary language and imagery of this poem. I especially wanted to do what the narrator promises us at the end of the poem that we can do in this distant place—the deep recesses of the human heart, perhaps?—"Drink and be whole again beyond confusion."

Other lines from the poem had also been running through my head since 9/11. As the narrator beckons us back to the abandoned house, farm and town, he instructs us:

And if you're lost enough to find yourself By now, pull in your ladder road behind you And put a sign up CLOSED to all but me.

Then make yourself at home. The only field Now left's no bigger than a harness gall.

First there's the children's house of make believe, Some shattered dishes underneath a pine,

The playthings in the playhouse of the children.

Weep for what little things could make them glad.

The children. Another image I could not get out of my head. The children, who, the newspapers told us, looked up at the bodies falling from the World Trade Center that day and said to their teachers, "Look! The birds are on fire!" My own three children, who loved nothing more than to drive to visit their grandparents in New York because the trip afforded vistas of the two tall buildings. My elder son, age 7, had visited the World Trade Center with his grandfather on August 29, just 13 days before the attack. One day several weeks later, after interviewing the widow of a man killed at the Pentagon, I walked through the upstairs hallway of our home and stooped to pick up a scrap of paper. It was Willies ticket for admission to the World Trade Centers observation area that day in August. Stamped across the top of the ticket was the single word, "Child."

Weep for what little things could make them glad. Weep also for the big things.

ONE AFTERNOON IN EARLY OCTOBER, THREE WEEKS after 9/11, my News Hour with Jim Lehrer colleagues and I headed to lower Manhattan to interview various people. The area was still closed to most vehicular traffic, but with special passes we were able to get through the police roadblocks and National Guard outposts. Acrid smoke still filled the air from the burning remains of the buildings. We made it to about a block from Ground Zero, then got out to survey the scene. It was an instant that seemed like a lifetime, for the sense of bottomless horror, anger and terror we felt. Again, I needed the outlet of poetry. Even horror needed sublime language to be fully expressed and, possibly, understood.

Later, I found no other words that could express the feelings better than those the poet William Blake had written two centuries earlier. In his poem, "Prologue, Intended for a Dramatic Piece of King Edward the Fourth," Blake had written: O for a voice like thunder, and a tongue To drown the throat of war! When the senses Are shaken, and the soul is driven to madness, Who can stand? When the souls of the oppressed Fight in the troubled air that rages, who can stand? When the whirlwind of fury comes from the Throne of God, when the frowns of his countenance Drive the nations together, who can stand? When Sin claps his broad wings over the battle, And sails rejoicing in the flood of Death; When souls are torn to everlasting fire, And fiends of Hell rejoice upon the slain, O who can stand? O who hath caused this? O who can answer at the throne of God?

SOMETIME AROUND NOVEMBER 2001, AFRIEND AND fellow poetry lover suggested I read W.H. Auden's "September 1,1939." Auden wrote the poem as he sat in a cafe in New York City, shortly after hearing the news that German tanks had just rolled into Poland. I opened one of my old college textbooks, eager to read it for what I thought would be the first time.

There it was, to my shock and sheepishness—the poem on the page, surrounded by annotations in my own handwriting. I can't recall reading the poem in college or how it struck me then. Perhaps I thought: What an extraordinary poem about cataclysmic events of long ago. When I read it again, post-9/11, I thought it was all too contemporary: Waves of anger and fear Circulate over the bright And darkened lands of the earth, Obsessing our private lives; The unmentionable odour of death Offends the September night.

There were even lines that seemed to foreshadow the fact that we would respond to 9/11 with a brutality—if an arguably justified one—of our own: I and the public know What all schoolchildren learn, Those to whom evil is done Do evil in return.

And, in closing, as in the closing lines of "Directive," there was another vague hint or hope of redemption: Defenceless under the night Our world in stupour lies; Yet, dotted everywhere, Ironic points of light Flash out wherever the Just Exchange their messages: May I, composed like them Of Eros and of dust, Beleaguered by the same Negation and despair, Show an affirming flame.

IT IS NOW EARLY 2003 AND MY THIRST FOR POETRY and my ongoing quest to order the experience of 9/11 haven't yet abated. It's also the Internet Age, so I go to the Web site of the Academy of American Poets at www.poets.org. The site was offering up poems for 9/11, including "In Those Years" by Adrienne Rich. Written in 1991, it speaks directly to the sense that, as much as anything, September 11 shattered our solipsism: In those years, people will say, we lost track of the meaning of we, of you we found ourselves reduced to I and the whole thing became silly, ironic, terrible: we were trying to live a personal life and yes, that was the only life we could bear witness to But the great dark birds of history screamed and plunged into our personal weather They were headed somewhere else but their beaks and pinions drove along the shore, through the rags of fog where we stood, saying I

WHAT DID I—WHAT DID WE—LEARN AT DARTMOUTH? I learned how to trail faithfully behind the greatest minds and talents in history as they opened the door into the human experience. My liberal education gave me tools to open a chest whose contents I didn't understand at the time, and still frequently don't. But, like James Freedman, I now understand why there are genres of comedy, of tragedy. I understand why poems must not mean, but be.

I have made my living since graduation as a journalistcovering the day to day, an observer of quotidian events large and small. After nearly a half century of life, and its attendant joys and triumphs, struggles and failures, I know in my heart the truth of what William Carlos Williams wrote about in his poem "Asphodel, That Greeny Flower": It is difficult to get the news from poems yet men die miserably every day for lack of what is found there.

Albert Camus is another writer whose work I read in college. I appreciated it at the time, but nowhere near as fully as I do now. He once said, "If, after all, men cannot always make history have meaning, they can always act so that their own lives have one."

Who among us can make the events of 9/11 have meaning? We can, however, give meaning and shape to our own lives, as Camus said. We can do that primarily by what we choose to do for others. And for me, meaning has also come from helping in a small way to perpetuate for future generations all the richness that is Dartmouth. For it is here that voices will forever cry out in the wilderness, as human beings like ourselves search for the path to understanding. And, thankfully, they will learn, as we learned, through the process of education, that there will be guideposts to mark the way.

IN UNCERTAIN TIMES, A LIBERAL ARTS EDUCATION SPEAKS TO US-IF WE HAVE THE STILLNESS AND COURAGE TO LISTEN.

"I needed the outlet Even horror expressed and, possibly, of poetry. needed sublime language to be fully understood."

SUSAN DENTZER is a correspondent for The News Hour with Jim Lehrer and the chair of Dartmouth's board oftrustees. She lives in Chevy Chase, Maryland.

Excerpts from "Directive" from THE POETRY OF ROBERT FROST edited by Edward Connery Lathem. Copyright 1947, ©1969 by Henry Hoi t and Company, ©1975 by Lesley Frost Ballan tine. Reprinted by permission of Henry Holt and Company, LLC. "September 1, 1939," copyright 1940 and renewed 1968 by W.H. Auden, from W.H. AUDEN: THE COLLECTED POEMS by W.H. Auden. Used by permission of Random House, Inc. "In Those Years" by Adrienne Rich from DARK FIELDS OF THE REPUBLIC: POEMS 1991-1995, published by W.W. Norton & Company. Copyright ©1995 by Adrienne Rich. Reprinted with permission. "Asphodel, That Greeny Flower," by William Carlos Williams, from COLLECTED POEMS: 1939-1962, VOLUME II, copyright ©1944 by William Carlos Williams. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryDoes Your Major Matter?

May | June 2003 By Lisa Furlong -

Feature

FeatureWhy an Engineer Needs English Lit

May | June 2003 By SAMUEL C. FLORMAN ’46, TH’46 -

Artifact

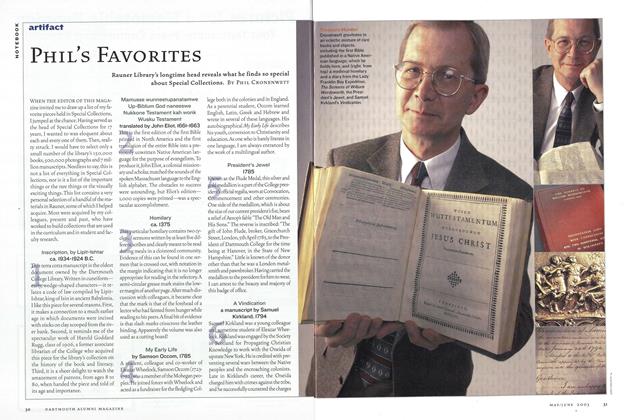

ArtifactPhil’s Favorites

May | June 2003 By Phil Cronenwett -

Personal History

Personal HistoryReminiscing In Tempo

May | June 2003 By Cliff Ennico ’75 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Global Classroom

May | June 2003 By Jack Shepherd -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

May | June 2003 By MIKE MAHQNEY '92

Features

-

Feature

FeatureBusiness Still Draws Its Share of Graduates

FEBRUARY 1965 By ADDISON L. WINSHIP '42 -

Feature

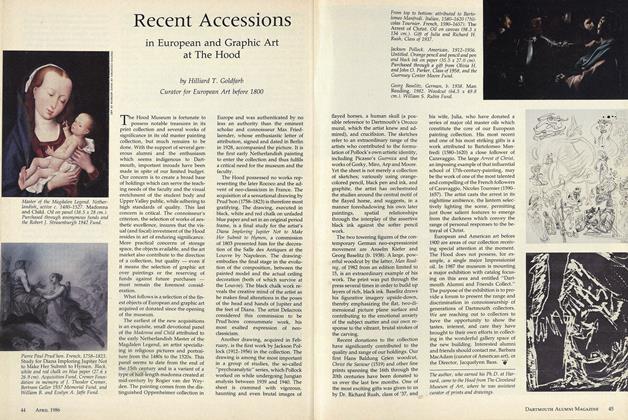

FeatureRecent Accessions in European and Graphic Art at The Hood

APRIL 1986 By Hilliard T. Goldfarb -

Feature

FeatureSkunks use only one chopstick

January 1974 By JONATHAN MIRSKY -

Feature

FeatureThe New Breed of Engineer

MARCH 1967 By MYRON TRIBUS -

Cover Story

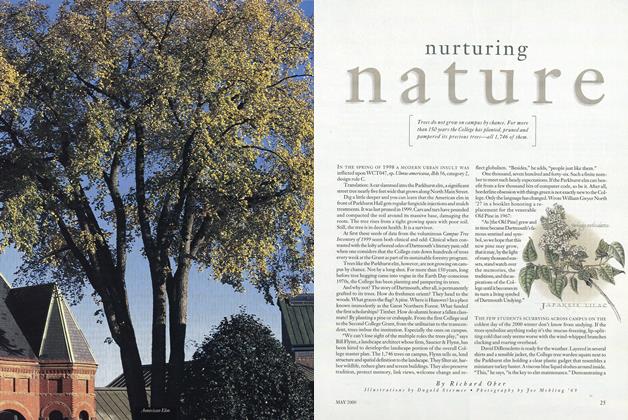

Cover StoryNurturing Nature

MAY 2000 By Richard Ober -

Feature

FeatureThe First 25 Years of the Dartmouth Bequest and Estate planning Program

September 1975 By Robert L. Kaiser '39 and Frank A. Logan '52