Why an Engineer Needs English Lit

The College has a proven path for educating well-rounded individuals. Too bad I didn’t follow it.

May/June 2003 SAMUEL C. FLORMAN ’46, TH’46The College has a proven path for educating well-rounded individuals. Too bad I didn’t follow it.

May/June 2003 SAMUEL C. FLORMAN ’46, TH’46THE COLLEGE HAS A PROVEN PATH FOR EDUCATING WELL-ROUNDED INDIVIDUALS. TOO BAD I DIDN'T FOLLOW IT.

Back in 1867, when General Sylvanus Thayer, class of 1807, gave Dartmouth the founding grant for an engineering school, it was his idea that a professional engineering education should rest upon a solid foundation in the arts and sciences, including the humanities. He was not interested in training mere technicians. He desired that the Thayer School seek out exceptional individuals and prepare them for what he called "the most responsible positions and the most difficult service." This commitment has prevailed at Thayer, where students are required to earn a bachelor of arts degree before they can go on to gain an engineering degree through a fifth year of study. In contrast, most of the nations 330 accredited engineering institutions confer engineering degrees after a four-year undergraduate program in which students take the fewest possible non-technical courses, usually the equivalent of no more than one semester.

As a civil engineer, a builder and self-proclaimed hardhat, I celebrate the Thayer tradition and preach about it to my fellow engineers—and others as well—every chance I get. Yet I didn't follow Sylvanus Thayer's design. The good general's liberal ideas got to me eventually by a circuitous route. I am moved to tell the story, partly byway of confession and partly to recall a unique time in the history of the College.

I came to Dartmouth in the spring of 1942, right after graduating from high school. Just six months had passed since our nations entry into World War II, but the College had already started to operate on a nonstop, year-round basis. Some of the older students were leaving to enlist in the armed forces, and the Navy had become a presence at Dartmouth with a variety of training programs. To a freshman, however, the campus seemed reassuringly normal. For a year and more, most members of our class had a gratifying taste of the Dartmouth experience, replete with good fellowship, football weekends and forays into the glorious New Hampshire countryside. The mil- itary had to be reckoned with, of course, and shortly after arriving in Hanover I enlisted in the Navy. The program I selected, however, permitted me to be a civilian student, subject to being called into active service at any time. So life went on, and a pleasant life it was.

In high school I had decided to become an engineer, and so at Dartmouth embarked on the academic program recommended for pre-engineering students. But a funny thing happened to me on the way to the Thayer School. When the Thayer deans—first Frank Garran and then Bill Kimball—recommended a series of humanities courses, I protested. With the Navy in my future, science and mathematics seemed much more important than literature and history. I resolutely defied the liberal approach that was at the heart of the Thayer tradition. The deans tried to change my mind and suggested that I would someday see the error of my ways. But with the war becoming ever more central to the communal mood, they let me have my way.

My anti-humanities attitude went beyond mere curriculum. During my student days the great poet Robert Frost was in residence at Dartmouth, and a dormitory mate of mine was part of a group that gathered in Frost's home one evening each week to talk about poetry—to talk about life. This friend arranged for me to be invited to these sessions, but I was invariably attracted to some other activity—sometimes work, often play. Today I simply cannot believe that I never saw Robert Frost at Dartmouth, much less spent an evening with him when I had the chance.

After about a year, a few of us pre-engineering students were called to active duty, put into uniform and subjected to military discipline. We stayed at Dartmouth as part of the Navy's V-12 program and found ourselves taking courses at the Thayer School—serious stuff like hydraulics, electronics and thermodynamics. There was no more talk about the liberal arts.

By early 1945 we had earned more than four years' worth of credits in three years, and the Navy decided that we were engineers. They sent us to Officer Training School in Quonset, Rhode Island, commissioned us as ensigns in the Civil Engineers Corps and shipped us off to join Seabee battalions in the Pacific. (Dartmouth, not knowing quite what to make of our accumulated credits, granted us bachelor of science degrees.)

I arrived in the Philippines on the very day that the peace treaty was signed with Japan. I soon found myself on the way to Truk, an atoll in the Caroline Islands, a one-time central Japanese naval base that had been bypassed during the westward counteroffensive in the Pacific. Truk is a tropical paradise, and life there was pleasant enough for a young engineer. During the day we worked on construction projects, repaying the airstrip with fresh coral dredged from the sea, erecting Quonset huts and building roads and a water-supply system. In the evenings we drank beer, played cards and talked—mostly about engineering, baseball and girls. The only officer in the battalion who was not an engineer was the chaplain. One night he joined several of us in a game of cards, and between hands he tried to interject some thoughts about the newly formed United Nations and prospects for international order. We did not respond. He then tried other subjects: the morality of nuclear weapons, the ethical responsibility of war criminals, politics, history, literature, the arts, religion—anything and everything that passes for civilized conversation. But each time we returned to our trivia. Even when he ventured to discuss the deeper meaning of engineering, the role of technology in making for a better society, we refused to become engaged. Finally the chaplain slammed his cards down on the table, looked upward and said in a loud voice: Dear Lord, I know that I am unworthy. I confess that I have sinned. But why did you have to punish me by putting me on this island with nobody for company but these boring engineers? What kind of a technology will these simpletons create? If they are our technical professionals, what sort of a world do we have to look forward to?"

I cannot say that from that evening forward my life was totally changed, but the experience started me thinking in new directions. I began to understand what the Thayer School concept was all about.

When I returned home to New York, before looking for a job—in engineering, which remained my true love—I spent a year earning a master's degree in English literature at Columbia University. Some time later the Thayer School faculty, under Dean Carl Long, amiably agreed that this could compensate for the liberal arts courses I should have taken at Dartmouth and granted me my five-year degree.

Today the importance of the liberal arts in engineering education is more widely recognized than it was during World War II, or even during the Cold Waryears. In the new global economy, with technology evolving rapidly in complex interdisciplinary ways and with public involvement an ever-more significant factor, effective engineers cannot rely upon technical proficiency alone. They must have an understanding of politics, psychology, history, economics and human nature and, perhaps most important of all, be able to communicate with many different sorts of people. Although Sylvanus Thayer's vision is proven increasingly valid every day—and continues to thrive at the school that bears his name—it has not been replicated at most institutions. Habit and economic pressures are partly responsible. So is the kind of youthful shortsightedness I exhibited so many years ago, before being set straight, on the other side of the world, by an exasperated chaplain.

SAMUEL FLORMAN is chairman of the Kreisler Borg Florman construction company in Scarsdale, New York. He has authored several books, including The Existential Pleasures of Engineering. Last year he receivedthe 2002 Civil Engineering History & Heritage Award from the AmericanSociety of Civil Engineers.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Affirming Flame

May | June 2003 By SUSAN DENTZER ’77 -

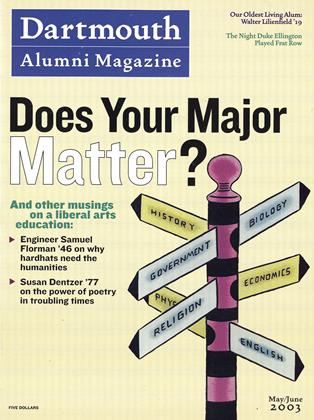

Cover Story

Cover StoryDoes Your Major Matter?

May | June 2003 By Lisa Furlong -

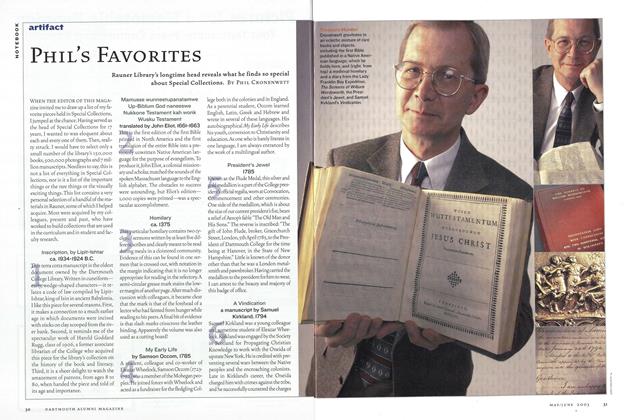

Artifact

ArtifactPhil’s Favorites

May | June 2003 By Phil Cronenwett -

Personal History

Personal HistoryReminiscing In Tempo

May | June 2003 By Cliff Ennico ’75 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionThe Global Classroom

May | June 2003 By Jack Shepherd -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

May | June 2003 By MIKE MAHQNEY '92

Features

-

Feature

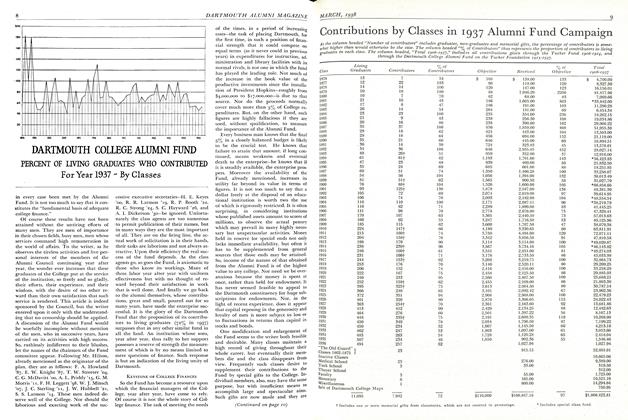

FeatureContributions by Classes in 1937 Alumni Fund Campaign

March 1938 -

Feature

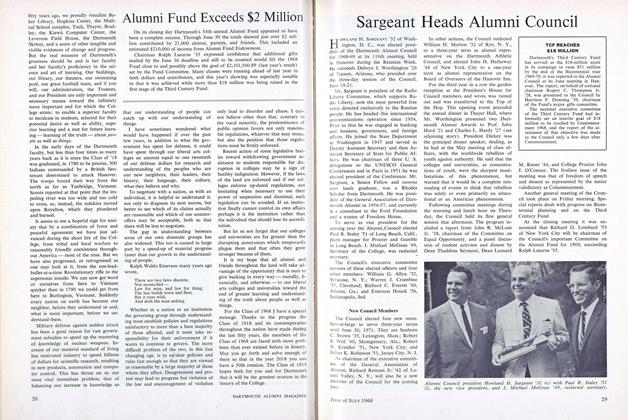

FeatureSargeant Heads Alumni Council

JULY 1968 -

Feature

FeatureRobert Reynolds Professor of Geology 12 mountains in a single grant

January 1975 -

Feature

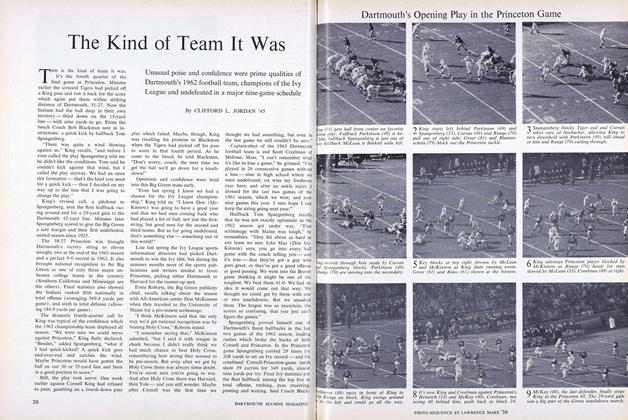

FeatureThe Kind of Team It Was

JANUARY 1963 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeaturePolitical Junkie

Nov/Dec 2000 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Feature

FeatureElegant Violence

May/June 2011 By MICHAEL GILLIS ’12