The ambitions of ALAN K. JACKSON '52 have been carefully channeled but his successes are by no means narrow. He founded and heads International Research Consultants, Inc., a unique organization headquartered in Geneva, with branch offices in Detroit; Paris; Milan; Miltenberg, Germany; and Princeton, N. J.

He is a sort of industrial catalyst for clients on both sides of the Atlantic, searching out opportunities for international expansion that others hadn't thought of or hadn't been able to bring off successfully. The Wall Street Journal recently cited him as one of a band of energetic young Americans - "Yankee hustlers" - who think internationally and who are stimulating a two-way exchange of products and research between Europe and this country.

Jackson explains his company: "In the beginning years of our growth, our emphasis was on looking in Europe for things which could be taken back to America. In recent years, our major activity has swung over to developing the European market for American products and processes."

Since high school, Jackson's views have been clearly defined. He applied to Dartmouth set on a career which combined his interests in business and engineering. Immediately after earning an M.S. at Tuck-Thayer in 1953, he received a direct commission in the Air Force and was sent to Wright-Patterson AFB in Ohio. His immediate superior was Jim Tobin '51, Tuck '52, and their group was responsible for purchasing research and development services for the Air Force.

Jackson describes it as "a thrilling job which resulted in considerable experience in engineering, finance, and law. I became thoroughly familiar with, what was to me, the new world of contract research. My present career is really a direct result of my military service."

If it wasn't a direct hop in 1955 from the Air Force to international business, it did lead to a six-month study of European research and development facilities on behalf of Business Week magazine. Jackson then spent a year and a half as business manager for a group of scientists he'd known from Air Force contacts. His nucleus of 15 scientist clients grew to 75. But he followed his yen to return to Europe with "a consulting contract from them and a half-time job as editor of European Engineering."

He founded IRCONSO in 1960 with $3000 he had raised by selling his Austin-Healey sports car. His arguments for its potential sounded deceptively simple; i.e., "If an American company has something a little special that has a good market at home, it can do equally well on the Continent."

IRCONSO has helped an impressive list of clients - among them: Avco Corporation, Avis Industries, Bendix Corporation, Goodyear Aerospace - and can assist them in market and sales development, product and process diversification, research, and special purchasing and manufacturing. Franklin Electric Company, the world's largest manufacturers of submersible electric motors had done an exhaustive market study in Europe but had not made any sales. After five years as IRCONSO clients their sales went from zero to $1 million.

Jackson's basic premise is irrefutable: European and American companies can profit from using each other's research and technical developments, and the man who brings them together can profit from the pairing, too.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"Mr. Hockey" By General Acclaim

February 1967 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN JR. '45 -

Feature

FeatureNous Étudiants à l'Étranger

February 1967 -

Feature

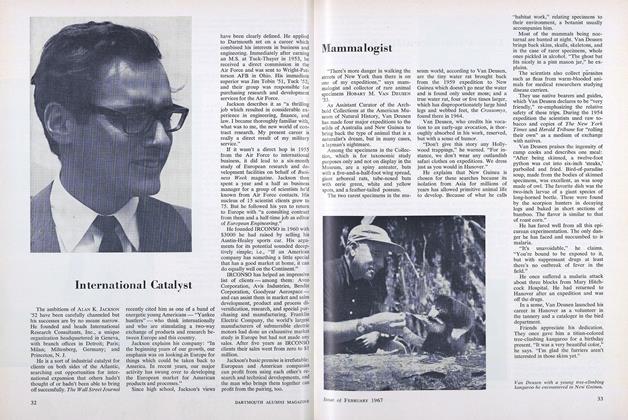

FeatureMammalogist

February 1967 -

Feature

FeatureSports Style-Setter

February 1967 -

Feature

FeatureCongressional Chronicler

February 1967 -

Feature

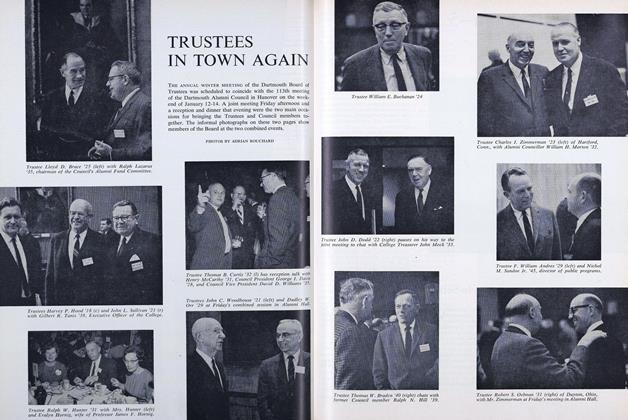

FeatureTRUSTEES IN TOWN AGAIN

February 1967

Features

-

Feature

FeatureCampus Cosmopolitans

February 1961 -

Feature

FeaturePursuing Sleep

February 1976 By B.K. THORNE, NANCY DECATO -

Feature

FeatureJohn Wheelock's Laws of Conduct and Regulations for Students

January 1962 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureAn Experiment in Dormitory Living

April 1955 By JOSEPH FRANKLIN MARSH '47 -

Feature

FeatureElegant Violence

May/June 2011 By MICHAEL GILLIS ’12 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO NAB GREAT FREE STUFF FOR YOUR REUNION

Sept/Oct 2001 By TOBY REILEY '81