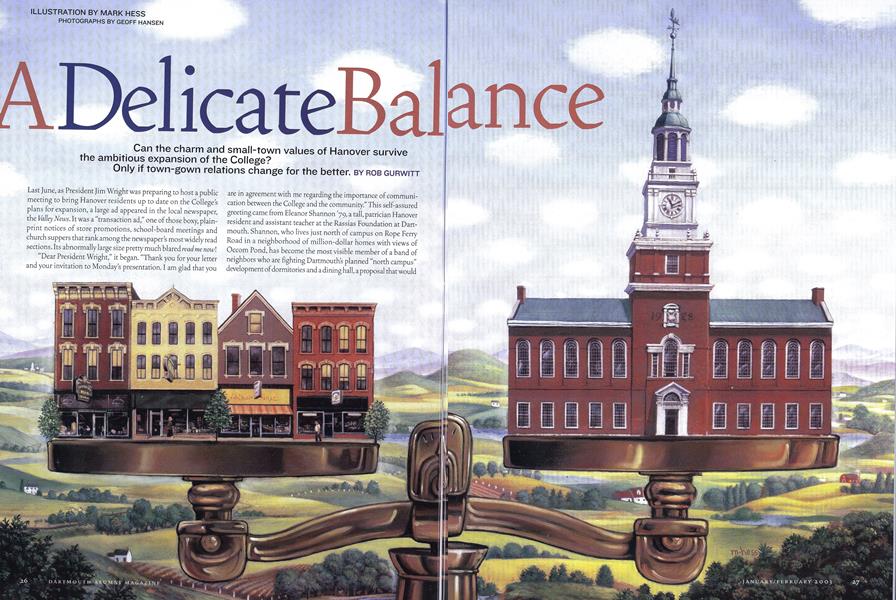

A Delicate Balance

Can the charm and small-town values of Hanover survive the ambitious expansion of the College?

Jan/Feb 2003 ROB GURWITTCan the charm and small-town values of Hanover survive the ambitious expansion of the College?

Jan/Feb 2003 ROB GURWITTCan the charm and small-town values of Hanover survive the ambitious expansion of the College? Only if town-gown relations change for the better, BY ROB GURWITT

Last June, as President Jim Wright was preparing to host a public meeting to bring Hanover residents up to date on the Colleges plans for expansion, a large ad appeared in the local newspaper, the Valley News. It was a "transaction ad," one of those boxy, plainprint notices of store promotions, school-board meetings and church suppers that rank among the newspaper's most widely read sections. Its abnormally large size pretty much blared read me now!

Dear President Wright," it began. "Thank you for your letter and your invitation to Mondays presentation. I am glad that you are in agreement with me regarding the importance of communication between the College and the community." This self-assured greeting came from Eleanor Shannon '79, a tall, patrician Hanover resident and assistant teacher at the Rassias Foundation at Dartmouth. Shannon, who lives just north of campus on Rope Ferry Road in a neighborhood of million-dollar homes with views of Occom Pond, has become the most visible member of a band of neighbors who are fighting Dartmouth's planned "north campus" development of dormitories and a dining hall, a proposal that would install some 500 undergraduates next door to one of the towns most handsome and expensive streets.

Her open letter was nothing if not polite. It supported the College in its efforts to "achieve excellence." It expressed Shannons hope that the College and the community could find a "positive, constructive" way to resolve their differences. And it delivered an unmistakable warning shot across the Colleges bow, mentioning that Shannon and her allies had hired an MIT planning professor to advise them and suggesting, by its presence in the newspaper, that they were prepared to scrap it out for public opinion. "Have your meeting," it all but declared, "but don't expect things to end there."

They haven't. The Hanover Neighborhood Alliance, Shannon's group, might have been named a bit ambitiously—it's mostly Rope Ferry Road neighbors—but it represents a striking development in town-gown relations: a concerted effort by a group of citizens, including alumni, to rewrite the way Dartmouth relates to the community around it.

There are people in town and at the College who dismiss the Neighborhood Alliances efforts by whispering that they are little more than the machinations of a wealthy few trying to protect their quality of life. The truth, however, is that Shannon and her neighbors have company. And it has become clear over the past several years that Dartmouth can no longer take the goodwill of many townspeople for granted.

These days, any College action that affects Hanover, including its recent golf course renovation and its efforts to help the local school district by offering to buy the Hanover High School property, is as likely to draw as much extended second-guessing and irritated letters to the editor as it does praise. At Hanover's annual town meeting last spring, residents shot down a series of zoning amendments pushed by the College to aid its development of several local sites. College employees who sit on town boards now find themselves suspected of conflict of interest when issues come up that affect Dartmouth. And as the College prepares an ambitious set of building plans both on campus and in the center of Hanover, it confronts an uncomfortable political fact: "Somehow," says Jonathan Edwards, Hanover's planning director, "the notion has increased that if it's good for the College, its not good for the town."

IT WAS THIS BELIEF THAT WRIGHT TRIED TO LAY TO REST at the community meeting that night in. June. In front of a packed Moore Theater at the Hopkins Center, he made a case for the Colleges plans—plans that are temporarily on hold as the College grapples with its financial difficulties—to build new dorms, new parking facilities, new research buildings and new housing for faculty and staff, and add a new look to a pair of downtown Hanover blocks the College bought a few years ago. In essence, he said, Dartmouth cannot afford to stand still if it wants to continue to attract top students, faculty and researchers. "This College has evolved over 230 years," Wright said, "and I don't think anyone is ready to say, 'That's enough!' The nature of our institution is to grow. This is a competitive environment. We need to address facilities issues that date back 30 years... .We do not have enough rooms for our students, we need more social and dining options for the student body, and we have long-deferred academic needs we're going to have to address."

Moreover, he argued, if it is in Dartmouth's interest to protect the quality of life in Hanover in order to attract employees and students, it is equally in Hanover's interest to help Dartmouth grow. "You have a stake in our ongoing capacity to bring in faculty and staff, performers and so on—this is a critical part of the vitality and energy of this community," he said. "We need each other to continue to be the strong places we are."

His speech drew a sympathetic response from the audience of Hanover residents—and even an enthusiastic one when Wright revealed that the College a few years ago had quietly donated the money necessary to conserve a parcel of land around nearby Mink Brook that was threatened with development. But for all his warm talk about communications," to many in attendance they seemed mostly oneway. During the question-and-answer session after the speech John Collier '72, Th'77, an engineering professor at the Thayer School, asked a question on behalf of his fellow town residents. "There is this premise that we need growth in order to improve," he said. "But at what point does growth become a negative? At what point does it impinge on the quality of life?" His unease pretty much summed up the prevailing anxiety in town, and it gave Wright a clear opening to engage the audience in a conversation about how the College and Hanover might work together to shape the town's future; instead, Wright insisted that the College, too, is interested in quality. When Martha Bailey, a former urban planner who retired to Hanover, asked why the College does not consult more closely with community residents as it draws up its plans, Wright answered that it deals with the town planning and zoning boards. "I don't quite understand the distinction between 'the town' and 'the community,'" he said. "We have to work with town officials."

The response was not reassuring to some in the audience. "I was staggered," says Bailey, who ran early planning workshops for the city of Boston in the neighborhoods that were going to be affected by its gargantuan, $14.6 billion Central Artery/Third Harbor Tunnel project known as the Big Dig. "It seemed to me so politically naive. What Dartmouth doesn't realize is that the community sees for the first time that the balance between Hanover and Dartmouth has the potential to shift. People look at the College's plans and go, 'I wonder if my lovely Hanover is going to be Hanover any more. We could lose the essence and spirit of this community.' "

To understand why this is so, it helps to know one overriding fact about Hanover: Its growth over the past decade has been nothing short of stunning. Its population, not including students, now stands at more than 7,400—a 30 percent jump from 1990, compared to 11 percent growth statewide. Some of these new residents are alumni returning to the fondly remembered scene of their college days, but a good number are only tangentially related to the College, such as Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center (DHMC) doctors and administrators, or they work for one of the high-tech engineering or software firms that have become an increasingly important part of the area's economy. They're also retirees drawn by the town's quality of life and its proximity to the resources of the College and the medical center, and they're what Julia Griffin, Hanover's town manager, describes as "urban refugees who did an online search for the six places with good schools, a high quality of life, clean air, good medical facilities and a low crime rate, then tossed a coin and here they are." And they are overwhelmingly well-educated and well-paid. Thanks to the College and DHMC, Hanover has long been somewhat wealthier than many of the towns around it, but it is unmistakably so now. In 2000 its median family income stood at $99,158, compared to $57,575 for New Hampshire as a whole. This means that about half the families in town earn more than $l00,000 a year.

There is an irony to this growth: It has filled Hanover with people invested in guarding its smalltown qualities and well-equipped to fight for them. "In advertising you talk about 'look, tone, feel,'" says Heidi Eldred, who is active in the Hanover Neighborhood Alliance and helps run a nearby auto dealership founded many years ago by her husband s step-grandfather. "Well, Hanover has a 'look, tone, feel' that's hard to describe—it's the small-town atmosphere, the intact Main Street, the fact that more than a few cars is a traffic jam, the mix of buildings. We're in danger of losing that look, tone and feel if we aren't very thoughtful." Sentiments such as this are not surprising coming from longtime residents, but they're just as fervently held—if not more so— by the town's newcomers. "There's a little bit of, 'Don't change it because this is what I came for. I used to live in Bronxville or San Francisco, and I don't want it to become what I.left,' " says town manager Griffin. Given that Hanover's growth rate shows no signs of slowing, the questions—of where its future residents will live, what will happen to its downtown, how much more traffic it can stand, how its schools will deal with more students, how to build affordable housing and regain something of its all-but-vanished mix of incomes—are all very much on townspeople's minds.

So as the College's building plans started to take shape over the past year, so did public apprehension about its activities. Part of this was free-floating— as history professor and longtime Hanover resident Jere Daniell '55 notes: "A lot of the people attracted to town are products of the massive anti-establishment movement we associate with the anti-Vietnam movement, but which was far broader than that. So they're suspicious of dominant institutions, and Dartmouth is the dominant institution." But residents' worries are also very specific. The list of projects the College wants to undertake is long. Though much of it is in abeyance at the moment due to economic constraints, the College's goals haven't changed (for more information about Dartmouth's building plans, see "strategic imperatives" at www.dartmout.edu/~stplan/). In addition to the new dorms and dining hall planned for the parking lots just south of the Medical School, both the Thayer and Tuck schools plan to expand and new academic buildings on campus are in the works; the College wants to build an immense new life sciences facility; the Hopkins Center is slated to expand; the College is developing new employee housing just out of town along Grasse Road; it wants to develop a new village center at Rivercrest, about a mile north of the campus, by adding some 200 units of housing; it proposes building a parking garage for up to 850 cars halfway up the hill from the Connecticut River; it wants to expand the parking lots just north of the Medical School; and it wants to build a new commercial and residential development with—tentatively, at least—up to 350 parking spaces, many underground, on two large downtown parcels it acquired a couple of years ago.

There are good reasons for all of the projects. Some of the justification stems from Wright's sense of what it will take to remain academically competitive. The housing projects arise from the tight housing market and the difficulty faculty and staff have had in finding a place to live. The new dorms are an effort to bring more students on campus and relieve pressure throughout town neighborhoods. At the same time, though, the College has reached a point in its development where it is difficult to grow without confronting hard trade-offs. "There have been three principles historically important to this campus," says Wright. "They've been to make it a walking campus, to make certain the buildings are of a scale vertically—that they're not too high and are appropriate to this community—and to make certain that there's a lot of green and open space around. If we face the issue of growth, we have to think about those three principles, because finally you can't protect each of them. You have to either be spread out, where you become less of a walking campus, you have to go upward, or you have to draw your buildings closer together. We're trying to juggle all three of these pieces."

Inevitably, much of this growth will take place on the College's fringes, which is why its immediate neighbors are on guard. But it has also placed a broader question squarely before town residents: How far are they willing to let the College go in defining Hanover? As Bill Baschnagel '62, a member of the town board of selectmen who is relatively sanguine about the Colleges intentions, puts it, "The element that makes this the neat community we have is the balance between the town and the College. It makes for an amazingly vital community. Id hate to lose that balance. So this issue of when do you stop, when have you crossed a boundary, is very difficult."

WHAT MAKES IT EVEN MORE DIFFICULT, OF COURSE, IS THE fact that Hanover wouldn't be the attractive town it is without the College. "If we didn't have Dartmouth, Hanover would be indistinguishable from Orford," says planning director Edwards, referring to the pleasant but sleepy town 18 miles north of Hanover. "We didn't have the water resources for a mill and we're not situated for rail, so we would have been a hard scrabble farming community."

The College does bring to town plenty of cultural resources, sporting events, intellectual vitality, retail dollars and sheer liveliness. But as Wright has said, "Dartmouth is not a foundation." Unlike its more urban counterparts, the College has not devoted millions of dollars to rejuvenating portions of the surrounding community, the way Trinity College has in Hartford, Connecticut, or the University of Pennsylvania has in Philadelphia; nor has it created a high-profile office to work with local officials and community leaders on economic revitalization, as Yale has in New Haven. But in less overt ways, Dartmouth has stepped in to help resolve tough issues facing its community. The preservation of the Mink Brook land, which cost the College $850,000, is "the most fundamental open space improvement the town has had for years," says Edwards. "It forms the final major link in the greenbelt around the Hanover Plain." The College was one of the moving forces behind a large subsidy to Advance Transit, the local transit agency, that makes local Hanover bus service free to all riders, including College employees. And in its Grasse Road development and proposal for Rivercrest, the College is striving to build moderately priced homes, a rarity in Hanover. "Yes, its for their employees and in their own long-term interest, notes Edwards, "but it's also good for the community."

The College has also stepped in at crucial junctures to help shape the town. For example, in the 1980s, when town officials decided that the medical center should not expand on its site next to the Medical School, the College's offer to buy the hospital land enabled the hospital to move to its current spot in Lebanon. The College's purchase of the downtown properties south of the post office replaced an owner who had let the properties run down, sometimes to a dangerous degree, and prevented an outside developer with no ties to the community from taking them over. And last summer the College's offer of money and land was central to helping the Dresden school district, which unites Hanover and Norwich, Vermont, develop a complicated agreement to resolve a knotty political debate over how to deal with its aging high school and middle school buildings. "The College was critically constructive in this, just as it was in enabling DHMC to move in the 1980s," says Brian Walsh '65, Th'66, who is chairman of the Hanover board of selectmen and was acting chair of the planning board when it turned down the hospital's request to expand.

Yet the College also has given ample ammunition to its critics. "You know Disney World? Well, this is Dartmouth World," says Hanover's senior planner, Vicki Smith '78. "The College is used to operating with casual reference to context and community."

The most glaring example of this was the imbroglio a few years back over the College's plans to expand the athletic facilities at Chase Field. Despite the fact that the fields were adjacent to a residential neighborhood, the College's initial proposal included lights and a blaring loudspeaker in use until midnight. It took a concerted fight by the neighbors—including the hiring of a lawyer—before the College backed down. "If they'd thought of the original proposal from any view but their own, they would not have come forward with it," says Edwards. "They were unrealistic to expect that noise and lights until midnight five nights a week would not meet opposition from the neighbors. And then they were slow enough to act and appeared not to hear the neighbors, so that when they changed the proposal not once, but twice, it appeared every concession was forced."

The College irritates Hanoverites in countless smaller ways. Several of its projects have run afoul of state or local environmental regulations—indeed, the town at one point took steps to shut down the Grasse Road development until the Colleges engineers dealt with runoff problems. And the Colleges neighbors are filled with stories of what amounts to boorish institutional behavior—road closures for construction during the morning rush hour, mechanical noises that run through the night, trucks and backhoes beeping all day long. Lots that are used for parking have also been used to house construction equipment—with their attendant noise and fumes—as well as for visiting sports team buses, which tend to keep their engines running for hours. "My plea is, if you're going to put in parking, restrict it to parking," Richard Nordgren, a pediatric neurologist at DHMC, told a town planning board meeting last June. "During the reconstruction of Baker Library, the lot near my house was used as a staging area—trucks started up at 4 a.m. so they were warmed up for the workers by 6 a.m. On Sunday afternoons there have been formula racing cars there, and there was a hovercraft down there one day. Sweeping of the lot started one Saturday night at 9:45." The College pledged in August to move the buses away from houses and stop storing the construction vehicles in parking lots, though only after being informed by town officials that ordinances forbid the practice. Even so, says Eldred, "When you go through it day after day, you stop trusting the College, and you go, 'You know what, guys? I live here, too!' "

This could easily be written off as the sort of friction that typically arises when people live next to a large institution. "I've heard a lot of horror stories about what it's like to be manager in a towngown town," says town manager Griffin. "The relationship here is extraordinarily positive compared to what a lot of my colleagues are dealing with." But in the developing politics of Hanover, tension between the College and its neighbors matters. When voters went to the polls in May, several of the proposed zoning changes they faced would have helped the College with its development projects, including downtown and at Rivercrest and Grasse Road; all but one were voted down by substantial margins. The sole survivor, which allows for denser building downtown—and hence for the Colleges planned development there—eked through in part because a coalition of downtown business people who had helped write it set up a table outside the high school and buttonholed residents as they came by to vote.

In this light, it was hardly a coincidence that Wright chose his public meeting to reveal the Colleges Mink Brook purchase—a move that had been made anonymously and kept secret for three years. College officials these days are clearly going out of their way to convince townspeople that they have Hanover's interests at heart. "Ultimately" says Paul Olsen, director of the Dartmouth real estate office, which manages all off-campus properties and projects, "people will realize that the College really does understand that its success depends on reinforcing the quality of life here and will do its best not to take away from that quality of life. The character here is incredibly important for the College. People make decisions on whether to come to Dartmouth, come back or give money to the College based on the character of the community." But the May zoning vote and rising scrutiny of the Colleges actions suggest that in a Hanover grappling with its future, goodwill-building assurances are not enough. Instead, the College is facing pressure to do something it has managed unevenly in the past: make consulting the community part and parcel of how it does business.

FROM AN INSTITUTION'S POINT OF VIEW, THIS IS NOT AN easy matter. Take downtown. Town officials are happy that the College bought the properties it did. "I'd rather have Dartmouth own that property than the investor who was there before or a bunch of small property owners who wind up creating a disjointed environment or an investor with no affinity or stake in the community," says Edwards. Yet the College's initial plans, which call for tearing down most of what is on those blocks and putting up much denser commercial and residential units, already have a few people in town hall on the alert—"It's hard to believe that development is going to happen at that scale," says senior planner Smith—and could well arouse much distress in the town as a whole once they become more public. "There's a lot of affection for this little downtown, and any change gets people alarmed," says town manager Griffin.

Or take the question of building dorms. On the one hand, there are neighborhoods in town—especially the one that runs along Maple Street, just west of downtown—whose houses have been cut into small apartments for students. Residents, tired of noise and junk on those streets, want the College to build dorms to bring more students on campus. On the other hand, when the College proposes building dorms, a different set of neighbors gets up in arms. So who is the "community" the College is being asked to consult? Small wonder the College prefers to work through official town boards. As Wright says, "It should not be our role to determine who represents the citizens of Hanover. We have to work with those bodies that have been designated for that purpose."

Yet town officials themselves have quietly been urging College administrators to adjust their approach. "I've told the College what I say to any developer: Long before you come to the town you need to have worked with the neighborhood," says Griffin. "Chase Field was a perfect example of what happens when that doesn't happen." This is a lesson that towns and cities—and not a few developers— all over the country have learned in the past few decades. "I can't think of a project that isn't better because of public participation," says Bailey, the retired urban planner, "and many projects with minimal participation (usually because a mayor wanted it that way) are poorer because they didn't have it."

Dartmouth officials say they do, in fact, meet informally with neighbors to discuss plans. The College also employs a part-time director of community relations."l certainly encourage my colleagues to keep communications open to neighborhoods and to try to explain what we're trying to do and our willingness to work with them," Wright says. "We try to talk to people who have concerns about what we're doing, and we look for ways to address those concerns that still enable us to do what we want to do." Yet townspeople have complained that College officials often come to them only after project planning is well along. "We get lectured to, we get presented to, but there's not a lot of talking with the neighbors," says Eldred.

The College recently has made some efforts to do things differently. In putting up new graduate student housing along North Park Street, it dealt extensively with the neighbors and even cut back the number of units it created in response to their concerns. Despite the noise and inconvenience of the construction, the College is improving once-unsightly housing without changing the nature of the neighborhood. People living nearby have expressed little unhappiness with it. Provost Barry Scherr would like to see the College pursue a similar model for future projects. "I'd like to say to people, 'Here are the plans, there are no secrets here,' " he says. "As we plan, we would like to bring people along earlier and try to involve neighborhood groups early on. It would be better to do that as you design, rather than present it finished to the planning board."

But there is a difference between consulting with town officials and community members with an aim toward getting as much as possible of what you want—and being open to sitting down and entirely rethinking what you want in light of community concerns. This is a difference illustrated by the College's dealings with the Rope Ferry Road neighbors, which have been far less amicable than those around the corner on North Park Street. The reason is that Eleanor Shannon and her allies don't just want cosmetic changes to the College's plans. They reject the whole idea of living next to dorms, a dining hall and, eventually, a life sciences facility whose square footage would dwarf the Medical School. "Let's say there are 40 homes in the entire Occom Pond neighborhood, 120 people or so," says John Gleason '76, an active member of the Hanover Neighborhood Alliance. "You're going to put hundreds of students and 70 labs in that neighborhood? There isn't one recreational field space there. Where will those students and employees go? How can you expand the population by 10 times and not affect the character of the neighborhood?"

Wright says there were never intentions to maintain the former hospital site as a parking lot forever. "We purchased that property from the medical center with an eye to expanding into that space," he says. "That's exactly what we're doing now." While the College has slowly revised its plans during six months of wrangling with town boards and in response to neighbors' arguments, Shannon says there is a larger point: "It's not 'Should they have the buildings?' It's 'How do we implement them in a way that's appropriate for the character of the town and the neighborhoods?'" In other words, how should Dartmouth grow in a community that's trying desperately to hang onto its small-town feel? The problem that both Hanover and the College face is that neither has any practice answering that question in a way that brings town and College officials together with Hanover residents. Nor does any forum exist for doing so.

One could be created, however. The College's recent announcement that it is holding off on new building projects until its finances improve gives everyone involved a window of opportunity. The model could be Hanover's recent approach toward downtown planning, in which a "visioning committee" of downtown merchants, neighbors, town officials and College administrators has worked for three years to come up with a detailed plan for what downtown should look like. Everyone involved agrees the process produced greater understanding and sympathy for the various players' concerns. "That model, common visioning, seems to me to be the answer," says Edwards. "It will take a lot of commitment from neighbors and the College, and probably a full-time position to manage it. It involves a fundamental change in attitude on the College's part for howyou plan a campus, and for how neighbors figure out what they want as opposed to what they don't want. Assuming the neighborhoods want to remain stable and retain their current character, and that the College wants to continue to evolve, can a genuinely representative group of neighbors sit down with the College on a regular basis and plan the future both for themselves and the College?"

Wright says he is open to the idea, but only if Hanover takes the lead. "If the town wants to establish some extra-official body to play a role," he says, "we'll obviously work with the town and try to work with that." Alternatively, there's another, darker scenario. With only 25 signatures required to put a zoning amendment on the town meeting ballot, it would not be difficult to come up with one imposing firmer restrictions on the Colleges use of its land. Given last May's zoning vote, it's hardly far-fetched that, should the College not engage with townspeople more fully than ever before, it could find itself mired in a bruising political battle. "Maybe this is the nuclear-winter scenario," says one towns person familiar with the politics of local growth issues. "But if it happens, it won't matter what the selectboard wants or the planning board wants or the College wants— the College will just end up on the short end. So my sense is that they need to act soon, or it could get much worse than it is now." a

Eleanor Shannon '79 of the Hanover Neighborhood Alliance

Hanover planning director Jonathan Edwards and town manager Julia Griffin

College President James Wright

ROB GURWITT writes about how communities deal with change for Mother Jones, Governing and Preservation. He lives in Norwich, Vermont.

It has become clear over the past several years that Dartmouth can no longer take the goodwill of many townspeople for granted.

We have a balance between the town and the College. It makes for an amazingly vital community. I'd hate to lose that balance." — Bill Baschnagel '62, a Hanover selectman

If the town wants to establish some extra-official body to play a role, we'll obviously try to work with that." —Dartmouth President James Wright

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

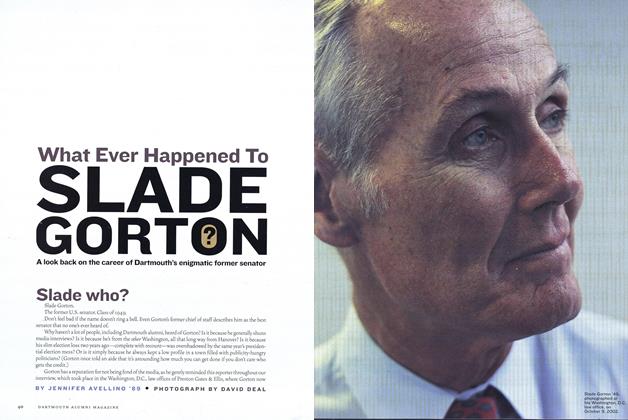

FeatureSlade Gorton

January | February 2003 By JENNIFER AVELLINO ’89 -

Feature

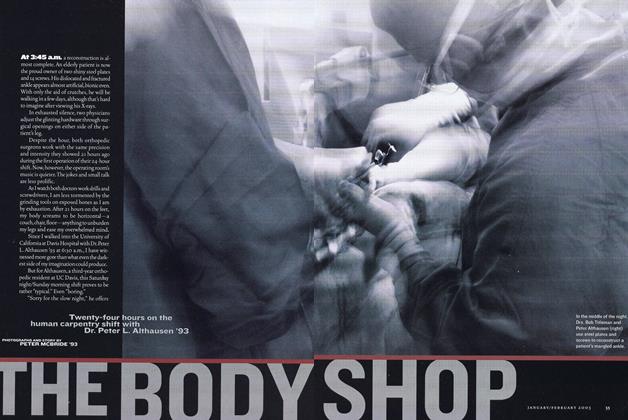

FeatureThe Body Shop

January | February 2003 By PETER MCBRIDE ’93 -

Personal History

Personal HistoryThe Serpent’s Call

January | February 2003 By BREEANNE CLOWDUS ’97 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

January | February 2003 By MIKE MAHONEY '92 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionPatriotism’s Perils

January | February 2003 By JAMES BERNARD MURPHY -

Article

ArticleThe Creative Spotlight

January | February 2003

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Ones To Watch

Jan/Feb 2010 By Brad Parks ’96 -

Feature

FeatureThe Erickson-Bismarck Plan

January 1962 By EPHRAIM ANIEBONA '64, ' AMIN EL-WA'RY '64 -

Feature

FeatureA Dartmouth History Lesson for Freshmen

December 1957 By FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06 -

Feature

FeatureReady to Roll

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2020 By RICK BEYER ’78